The King Mongkut Studies Initiative

Unveiling Siam through Architecture: Tracing Landmark Sites from the Reign of King Rama IV

The Practice of Hosting the Rotating Monastic Alms Offering in the Palace

The Royal Merit-Making Ritual of Offering Alms to Monks on Palace Duty

(From “The Royal Merit-Making Ritual of Offering Alms to Monks on Palace Duty” by Paisarn Piammettawat, 2015, in Siam Through the Lens of John Thomson 1865–66, Including Angkor and the Southern Ports of China, p.67)

Phra Thinang Sutthaisawan was the principal royal pavilion situated to the east of the Phra Aphinao Niwet group. His Majesty King Mongkut graciously commanded its restoration in B.E. 2396 (A.D. 1853), and thereafter used it as the place for daily royal merit-making ceremonies, where monks on palace rotation (phra wet) were invited to receive offerings. In the image referenced, His Majesty was pleased to appoint His Royal Son, Prince Thongtham Thawalyawong, to represent Him in this religious duty.

Sutthai Sawan Thorne Hall is section of the throne hall with in the Para Aphinao Niwet complex. In 1853 king RAMA IV renovated the building and use to offering lunch to Buddhist monks. In the picture king RAMA IV is precoding over the ceremony and has been identified as Prince Thongtaem.

Phra Thinang Aphorn Phimok Prasat

Phra Thinang Aphorn Phimok Prasat, commissioned by King Mongkut (Rama IV), was constructed to serve as a royal changing pavilion for His Majesty to don ceremonial attire before proceeding to formal state processions—particularly those requiring the monarch to be seated on a Phra Ratcha Ranyang (royal palanquin). It was used on grand occasions such as the Royal Procession during the Coronation Ceremony and the Ceremonial Royal Progress around the capital (Leab Phra Nakhon).

Architecturally, the pavilion is a small wooden structure in the form of a chaturamukha prasat—a four-gabled spired hall—elegantly perched atop the inner wall (kamphaeng kaeo) near Phra Thinang Dusit Maha Prasat. Though modest in scale, it is celebrated for its refined craftsmanship and symbolic function, embodying the fusion of royal ritual, religious decorum, and Siamese architectural sophistication during the mid-19th century.

This photograph is the Aporn Phimok pavilion, which was built by King Rama IV as a place to change his robes when taking part in land procession.

Phra Thinang Aphorn Phimok Prasat

From: “Phra Thinang Aphorn Phimok Prasat” by Paisarn Piammatthawat, 2015, in Siam Through the Lens of John Thomson 2408–09, Including Angkor Wat and the Coastal Cities of China, p. 75.

Phra Merumat (Royal Crematorium) of His Majesty King Pinklao

Royal Crematorium of His Majesty King Pinklao

From “Phra Merumat of His Majesty King Pinklao” by Paisarn Piemmettavat, 2015, Siam Through the Lens of John Thomson 1865–66, including Angkor Wat and the Coastal Cities of China, p. 77.

The Royal Crematorium (Phra Merumat) was a temporary architectural structure built for the royal cremation of Thai monarchs and members of the royal family, in accordance with ancient beliefs that upon death, the sovereign ascends back to the celestial heavens—their original divine abode.

The design of this specific royal crematorium was notably grand. It featured a large quadrangular prang-topped structure (prasat jaturamuk) with seven tiers of ornamental platforms (ching-khlon), reaching a height of 40 meters. At the four cardinal points stood smaller prangs, while the central spire rose high into the sky. Between the eastern, western, and southern directions were halls for the royal family: on the south side stood the Phra Thinang Song Tham (Royal Sermon Hall) for King Mongkut (Rama IV) and the inner court royals; to the north was another Song Tham pavilion designated for Front Palace (Wang Na) royals.

The construction of wooden meru for royal cremations is a long-standing Thai tradition. In Thai cosmology the meru upsent Mount Meru. The King’s urn is housed inside.

The angle is slightly different and so the main meru and the smaller east directional Phra Meru appear twice in all there were four directional meru. On the left of Photograph is the Phra Thinang Song Than where the King would listen to sermons together with his immediate family

Golden Mount (Phu Khao Thong)

The Golden Mount chedi was originally conceived under the reign of King Rama III, who wished to replicate the Phu Khao Thong stupa of the ancient capital Ayutthaya. The original architectural plan featured a prang (tower) with a square base built in the yom mai sip song style (twelve indented corners), a form of sacred Buddhist architecture. Its foundation was deeply excavated and reinforced with tightly packed logs forming a raft, then filled with soil and laterite stones, with a brick-and-mortar shell built around the exterior.

However, the foundation could not support the immense weight of the upper prang, causing the top to collapse under its own weight. As a result, construction halted, and the project remained incomplete for some time.

During the reign of King Rama IV, the abandoned structure was revived. He ordered the repairs of the ruined base and oversaw the construction of twin staircases spiraling upward to the summit. In May 1865 (2408 B.E.), he commissioned a new stupa of inverted bell shape to be constructed atop the mount. Upon its completion, he bestowed the name Borommabanphot (บรมบรรพต) upon the sacred monument.

The construction of this temple was ordered by King RAMA III Who wanted to mimic the Golden Mount, which had existed at Ayutthaya. When it was first built it had a prang on a enormous, square redented base. The dup Foundations were lined with teak logs overlaid with laterite, brick and rubble. However, as construction progressed the weight of the brick walls were too great for the foundations and work was abandoned

In the Fourth Reign, the King ordered that work be us tarted but modified the design by enclosing the massive base, creating two circular staircases, and building a bell-shaped stupa on the top

Golden Mount (Phu Khao Thong)

From “Phu Khao Thong” by Paisarn Piemmettawat, 2015, Siam Through the Lens of John Thomson 2408–9 Including Angkor Wat and the Coastal Cities of China, p.109

ChatGPT said: Wat Chumphon Nikayaram, Bang Pa-In, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya

Wat Chumphon Nikayaram, Bang Pa-In, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya

From Wat Chumphon Nikayaram, Bang Pa-In, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya by Paisarn Piemmettawat, 2015, Siam Through the Lens of John Thomson 2408–9, including Angkor Wat and the Coastal Cities of China, p.112.

The ordination hall (ubosot) of Wat Chumphon Nikayaram is located on Hat Island, Bang Pa-In. This temple was originally constructed by King Prasat Thong in B.E. 2175 (A.D. 1632). It underwent a major restoration during the reign of King Mongkut (Rama IV) in B.E. 2406 (A.D. 1863). In the image, the ubosot is shown in the architectural style favored during the reign of King Rama IV. Modest in scale, it is enclosed within a low kampaeng kaeo (ceremonial wall). The building features projecting porticos (muk det) at both the front and rear entrances. The door and window pediments are elaborately decorated with gilded stucco and inlaid glass, fashioned into mondop forms topped with prang spires. Child-like faces adorn the pediments, and the royal emblem of the reign—Phra Maha Phichai Mongkut, the royal great crown—appears prominently as a sign of its renovation under Rama IV.

King Rama IV ordered the restoration of Several temples the ubosot is next to the royal place of Bang Pa-in and was built by King Prasat Thong in 1632 the style is typical of Fourt Reign temples with a low well and two smaller porches at the front and back. The window surrounds are in Prasat style topped by a thin prang and with small pediments bearing the emblem of King Mongkut.

King Mongkut Bridge, Phetchaburi Province

This bridge spans the Phetchaburi River and was originally built during the reign of King Mongkut (Rama IV). It was formerly known as “Hua Chang Bridge” (Elephant Head Bridge). In honor of King Mongkut’s contributions to the people of Phetchaburi, the government later renamed it “Phra Chom Klao Bridge.”

The bridge features reinforced concrete construction with large piers supporting the structure across the river. Both banks are equipped with stairways serving as landing points for loading and unloading goods from boats to land.

The construction of this temple was ordered by King RAMA III Who wanted to mimic the Golden Mount, which had existed at Ayutthaya. When it was first built it had a prang on a enormous, square redented base. The dup Foundations were lined with teak logs overlaid with laterite, brick and rubble. However, as construction progressed the weight of the brick walls were too great for the foundations and work was abandoned

The bridge was bridge was Bulit of reinforced concrete with three large piers standing in the river. It was lere that the wooden barges with bamboo roof such as those shown would moor to lead and unload their carge,

ChatGPT said:

King Mongkut Bridge, Phetchaburi Province

From “Saphan Chom Klao, Changwat Phetchaburi” by Paisarn Piammatthawat, 2015, Siam Through the Lens of John Thomson 1865–66, Including Angkor and the Coastal Cities of China, p.112.

Wat Ratchapradit Sathitmahasimaram Ratchaworawihan

Wat Ratchapradit Sathitmahasimaram — Aerial Photograph, 1946 (B.E. 2489)

(Image from “Wat Ratchapradit Sathitmahasimaram” by M.R. Nengnoi Suksri, 2006, in Phra Aphinao Nivet: The Royal Residences of King Mongkut, p.168)

This temple was founded in 1864 (B.E. 2407) by King Mongkut (Rama IV), who personally purchased the land—formerly a royal coffee plantation—with his own private funds. The architectural design of the temple incorporates Western elements and symbolizes the meaning behind the King’s royal name. The interior of the ordination hall (ubosot) is adorned with chandeliers, and the original scripture library (ho trai) was built in the form of a miniature prasat (royal throne hall) modeled after the Dusit Maha Prasat Throne Hall. The temple was named “Wat Ratchapradit Sathitmahasimaram,” reflecting its royal foundation and enduring sanctity.

This temple was constructed in 1864 after King Mongkut purchased a former coffee plantation, which was royal land, using his personal funds. The temple features Western-style architecture that reflects the meaning of the founder’s royal name. The interior of the main sanctuary (ubosot) is adorned with chandeliers, and the original Tripitaka Hall (ho trai) was designed as a miniature replica of the Dusit Maha Prasat Throne Hall. The temple was royally named “Wat Ratchapradit Sathitmahasimaram

Phra Nakhon Khiri (Khao Wang)

Phra Nakhon Khiri, commonly known as Khao Wang, is a historic palace complex atop a three-peaked hill in Phetchaburi. Built as a summer palace by King Mongkut (Rama IV), it blends royal elegance with scenic beauty. The King named it “Phra Nakhon Khiri,” but locals still refer to it as Khao Wang.

In 1861 (B.E. 2404), the palace notably hosted Russian envoys, symbolizing Siam’s emerging diplomacy and modernization during King Mongkut’s reign.

Phra Nakhon Khiri (Khao Wang) is an ancient historical site and a landmark of Phetchaburi province. This summer palace was constructed during the reign of King Mongkut (Rama IV) on the summit of three large hills. The King bestowed the name “Phra Nakhon Khiri,” meaning “Holy City Hill,” but the local people have long preferred to call it “Khao Wang,” Phra Nakhon Khiri Palace has been a prominent and esteemed site since ancient times. In 1861, it notably welcomed a Russian envoy who came to establish diplomatic relations.

Phra Nakhon Khiri (Khao Wang)

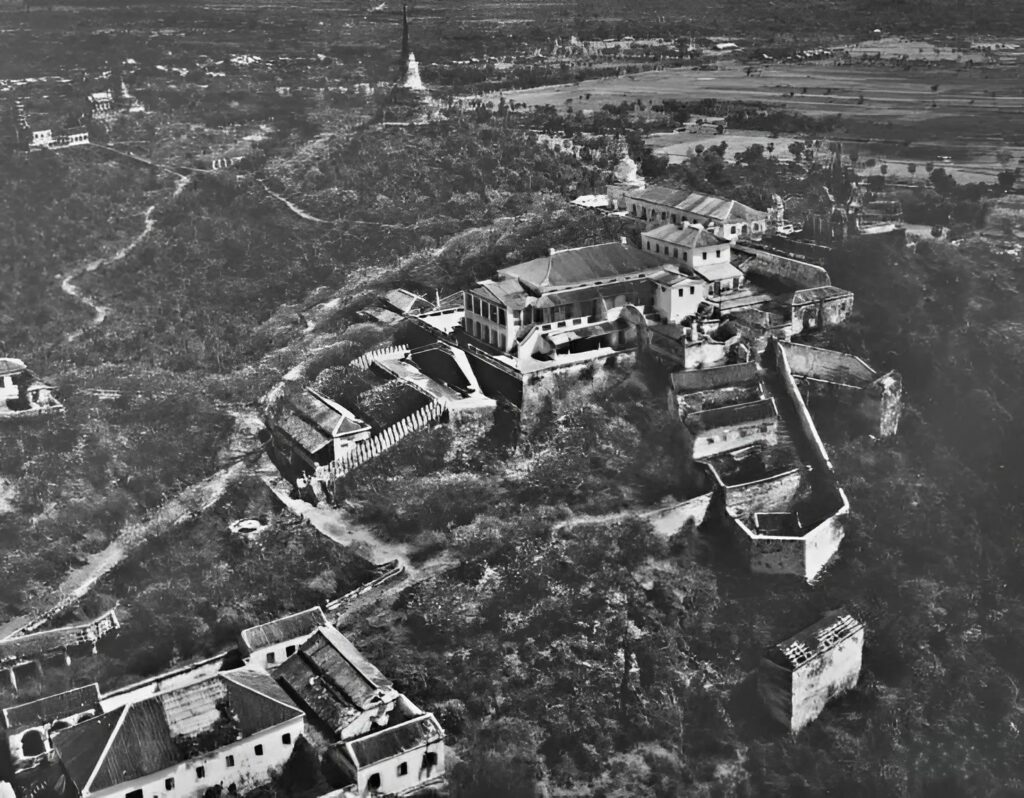

Aerial photograph of Phra Nakhon Khiri taken in 1946 (Source: National Archives of Thailand)

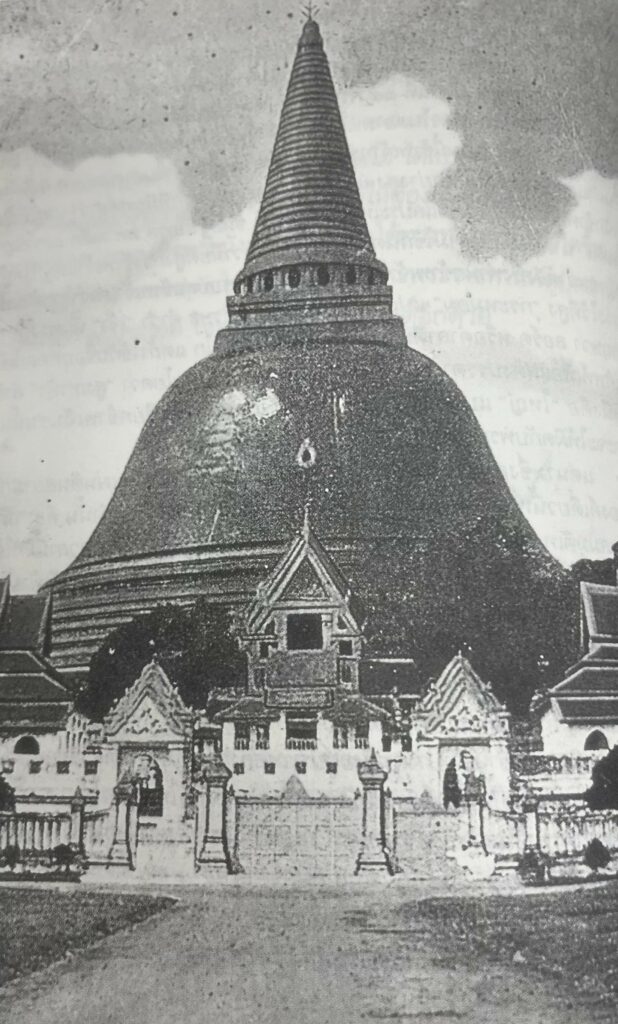

Phra Pathom Chedi, Nakhon Pathom Province

Phra Pathom Chedi, Nakhon Pathom Province

(Source: “Sadet Hua Mueang” by S. Phlainoi, 2001, Phra Bat Somdet Phra Chom Klao Chao Yu Hua Phra Chao Krung Sayam, p.59)

The original Phra Pathom Chedi is believed by archaeologists to have been constructed during the time when Nakhon Pathom was a prominent city of the Dvaravati Kingdom, possibly under Srivijaya influence. It was built as a grand stupa to signify the power and presence of Theravāda Buddhism in the region.

Later, during the reign of King Mongkut (Rama IV), while he was still a monk, he is said to have come across the ancient chedi during his forest pilgrimage. Observing its abandoned state, he recognized its historical and religious significance—believing it to be a sacred site housing relics of the Buddha. Upon ascending the throne, he ordered the restoration and reconstruction of the chedi, encasing the original structure within a new, larger one, giving rise to the monument as we see today. The restored stupa was named “Phra Pathom Chedi,” meaning “the first sacred stupa,” acknowledging its revered status as possibly the oldest Buddhist monument in Thailand.

Archaeologists hypothesize that the original Phra Pathom Chedi was constructed during the era when Nakhon Pathom was the Sri Vijaya city of the Dvaravati Kingdom. A large stupa was built to proclaim the grandeur of Buddhism. Later, during the reign of King Mongkut (Rama IV), while he was a monk, he journeyed to Phra Pathom Chedi on a pilgrimage. He surmised that this chedi was likely a significant ancient monument enshrining relic of the Buddha from ancient times but had been abandoned. Consequently, he initiated its restoration, building a new, larger chedi to encompass the original one. He then named this chedi “Phra Prathom Chedi.”

Ananta Samakhom Throne Hall

The original Ananta Samakhom Throne Hall (Phra Thi Nang Anantasamakhom) referred to one of the throne halls within the complex of Phra Aphinao Nivet, constructed during the reign of King Mongkut (Rama IV). This throne hall served an important ceremonial and diplomatic function in the early days of Siam’s engagement with the West.

One of the key royal duties carried out by King Mongkut at this Ananta Samakhom was receiving foreign envoys and diplomatic representatives. The hall was used for official audiences with ambassadors and emissaries who arrived in the capital to negotiate or deliver treaties of friendship and trade or to present insignias and royal decorations bestowed by foreign monarchs and governments.

The original Ananta Samakhom was the name of a throne hall within the Phra Aphinao Niwet complex, constructed during the reign of King Mongkut (Rama IV). Significant royal duties performed by the King at the Ananta Samakhom Throne Hall in Phra Aphinao Niwet included receiving envoys who came to present treaties of friendship and receiving representatives from various countries who offered royal decorations.

Ananta Samakhom Throne Hall

(Photograph courtesy of the National Archives of Thailand, Fine Arts Department)

Phra Phat Phiphitthaphan Throne Hall

Bangkok National Museum

(Source: Sarakadee)

The Bangkok National Museum (Phiphitthaphanthasathan Haeng Chat Phra Nakhon) is recognized as Thailand’s first public museum. It was officially established in 1859 (B.E. 2402) during the reign of King Mongkut (Rama IV). Originally, the site was part of the “Phra Ratchawang Bowon Sathan Mongkhon” — commonly known as the Front Palace or Wang Na, the residence of the vice king.

In the early years, King Mongkut initiated the creation of a private royal museum within the Phra Phat Phiphitthaphan Throne Hall to preserve and exhibit various antiquities and artistic objects, including many diplomatic gifts and rare treasures. This marked the first formal effort to establish a space dedicated to the collection, preservation, and display of cultural and historical artifacts for educational purposes

The National Museum Bangkok holds the distinction of being Thailand’s first public museum. Established in 1859, it was originally the “Bowon Sathaan Mongkhon Palace” or the Front Palace. During the reign of King Mongkut (Rama IV), he established a private museum within the Phra Thinang Prapas Pipitaphan (a hall or building named “Prapas Pipitaphan”) to preserve antiquities and artifacts, including royal tributes.

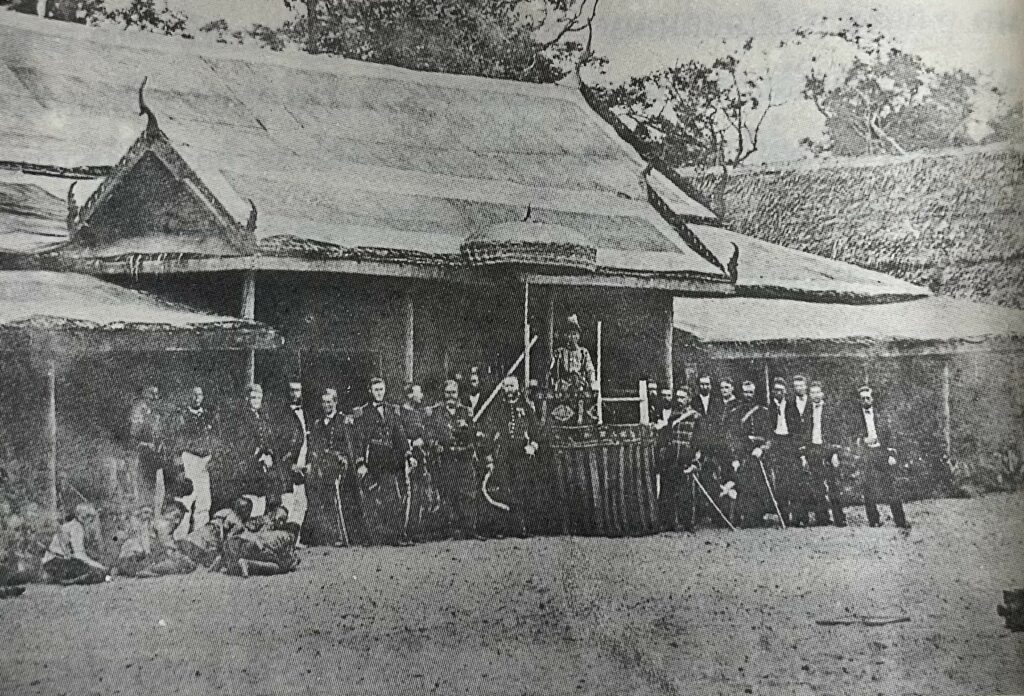

Wagor, Prachuap Khiri Khan

The guest pavilion constructed for the reception of Sir Harry Ord and his entourage was made of split bamboo and thatched with dried palm or nipa leaves. The structure measured approximately 140 feet in length and 50 feet in width. It was divided into two main sections. The larger section served as a dining hall capable of accommodating around 50 people. Both wings of the building were raised on stilts about 3 feet high, and were divided into 12 small rooms.

At the rear of the main pavilion stood a smaller house, containing two bedrooms and two dressing rooms, complete with a veranda used as a sitting and reception area. Unlike the main structure, the floor and walls of this smaller section were made entirely of wood, offering greater comfort and stability for distinguished guests.

The Siamese side extended exceptional hospitality, dispatching French and Italian chefs along with Thai assistants to provide meals throughout the day. The visitors were served with gourmet dishes brought from Bangkok and Singapore, accompanied by a wide selection of wines and an ample supply of ice. The delegation from Singapore was astonished by the unexpected luxury in such a remote location, having not anticipated the refined arrangements and quality of service they encountered at this distant coastal outpost.

The residence of Sir Harry Ord and his delegation was constructed from split bamboo and roofed with dried palm or nipa leaves. It measured approximately 140 feet in length and 50 feet in width, divided into two main sections. The larger section served primarily as a dining hall, accommodating around 50 people. Both wings of the structure were raised about 3 feet off the ground and divided into 12 small rooms. At the rear of the main building stood a smaller house, which contained two bedrooms and two dressing rooms, along with a veranda used as a sitting and reception area. The floors and walls of this section were made entirely of wood.

The Siamese hosts extended exceptional hospitality, providing French and Italian chefs, assisted by Thai staff, to serve meals throughout the day. These included exquisite dishes brought from Bangkok and Singapore, a variety of wines, and generous quantities of ice. The delegation from Singapore was astonished by the unexpected luxury found in such a remote location.

King Mongkut (Rama IV) seated on the front porch of the royal pavilion

(Image from “The Solar Eclipse at Wako” by S. Playnoi, 2001, in King Mongkut of Siam, p. 242)