The King Mongkut Studies Initiative

The New Face of Thai Education in the Reign of King Rama IV

Compiled and edited by Sompong Pongmaitri and Supap Klinrueang

Traditional Thai education, prior to the influence of the West, followed a jarit (customary) model. This system consisted of three main stages: literacy training, monastic education, and specialized instruction. Educational access and content were also shaped by the learner’s social status, including class and gender.

Following the arrival of Western influence, Thai education began to change during the reign of King Rama III. Missionaries from various organizations arrived in large numbers, with their initial aim being the spread of Christianity among the Chinese community in Bangkok. In later years, these missionaries gradually extended their activities to regional provinces beyond the capital.

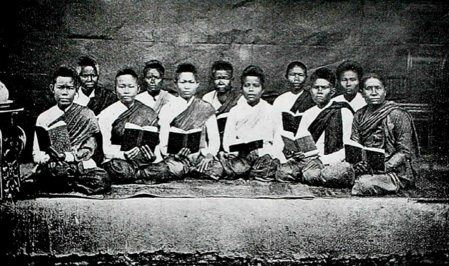

Missionaries who came to spread religion and Western knowledge.

Although the missionary groups were largely unsuccessful in converting many Thais to Christianity—as evident in Dr. Dan Beach Bradley’s own account of disappointment, noting that he could not convert even a single Thai person—they nonetheless introduced a wide range of Western knowledge and cultural practices to Siam, particularly in the field of education. In 1836 (B.E. 2379), Dr. Bradley brought with him a Thai printing press and type, and established a printing house near the mouth of the Bangkok Yai Canal. Much of the printed material focused on religious texts, both Buddhist and Christian. Dr. Bradley also launched a Thai-language biweekly newspaper called The Bangkok Recorder, followed by an English-language annual publication titled The Bangkok Calendar. These publications became early models for Thai journalism and played a crucial role in promoting literacy and reading culture in the kingdom.

While still in the monkhood, King Mongkut displayed a keen interest in a wide range of fields, especially Western sciences and knowledge. He established the first Thai-operated printing press at Wat Bowonniwet Vihara, with the aim of printing Buddhist scriptures and official documents. In addition to his scholarly pursuits, he also studied foreign languages—Latin with Bishop Jean-Baptiste Pallegoix, and English with Jesse Caswell, an American missionary, both at Wat Bowonniwet.

His proficiency in English served as a key that unlocked access to a broad spectrum of modern knowledge. The educational transformation initiated during King Rama IV’s reign marked a shift from a traditional society, rooted in long-standing customs and monastic learning, toward a modern society, influenced by Western ideals. However, this modernization was not an imitation, but rather an adaptation shaped by Thai cultural identity.

A New Face of Thai Education

After King Mongkut (Rama IV) ascended the throne, Thai society began to undergo significant transformation under growing Western influence—particularly in the area of education among the nobility. The elite became increasingly aware of the need to study Western sciences and languages. King Mongkut himself possessed a strong foundation in Western knowledge and languages, having studied extensively during his years as a monk. He fully recognized the importance of foreign language education, viewing it as the gateway to understanding the broader body of Western knowledge.

Western-style schools began to emerge during his reign, accompanied by the arrival of foreign teachers who were invited to instruct within the royal palace. At the same time, Christian missionaries opened schools to educate the children of commoners.

According to Dr. Dan Beach Bradley’s writings in “Siam in Three Reigns,” just a day before a royal prince was to leave the monkhood, King Mongkut—who had long maintained close ties with Protestant missionaries—summoned them for a private audience. During this meeting, the King spoke candidly and without formality. His words rekindled hope for the future progress of Siam. What truly captured attention was his declaration to establish large classrooms where Siamese youths could study English thoroughly, and his intention to open a secondary school in Bangkok that would teach both English and Western sciences.

True to his vision, within just six months of his coronation, King Mongkut began implementing these educational reforms. He especially wished for members of the royal family to receive an education comparable to that of royal courts in Europe.

Prince Manusyanagamanop (Somdet Phra Maha Samana Chao Krom Phraya Vajirananavarorasa)

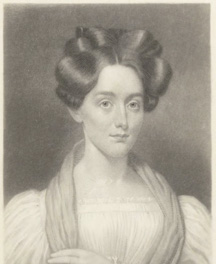

Royal princes and grandsons in the royal family studied English with Mr. Francis George Patterson.

According to Royal Autobiography Narrated by Himself, a royal chronicle written by Somdet Phra Maha Samana Chao Krom Phraya Vajirananavarorasa—the 47th son of King Mongkut—there is a passage recounting:

“It began when His Majesty wished to nurture our learning. He established an English school in a row house by the Phiman Chai Si Gate, on the right-hand side when facing outward. Mr. Francis George Patterson was appointed as the English teacher, under the supervision of Chao Phraya Phasakornwong. In the mornings, he taught royal children and some Mom Chao (minor princes); in the afternoons, he taught court officials from the royal guards. I had attended the school since its opening, at around the age of twelve. The teacher could not speak Thai, and his teaching style was fully Western. Textbooks were foreign; even the maps we used were European. I came to know the geography of Western countries before that of my own. Mathematics was taught using English units. We came to understand Western habits through their textbooks…”

Additionally, according to records by Dr. Haws in 1851 (B.E. 2394), King Mongkut instructed the missionary group to send female missionaries to teach English to royal princesses and other noblewomen in the Grand Palace. The women who undertook this role included Mrs. Dan Bradley, Mrs. S. Mattoon, and Mrs. John Taylor Jones, who served as English teachers to the royal women for a period of three years.

The female missionaries consisted of Mrs. Bradley (wife of Dr. Dan Beach Bradley), Mrs. Mattoon (wife of Dr. Mattoon), and Mrs. Jones (wife of Dr. Jones). They served as English and general knowledge instructors for the noblewomen in the royal court during the years 1851 to 1854 (B.E. 2394–2397).

Nonetheless, the fact that missionaries were permitted to teach within the Grand Palace may be regarded as the establishment of the first school for women in Thailand. The school had as many as 30 students and three instructors. However, it was considered a royal school, not a private one, as it was founded by royal command. This marked the first time in Thai history that women began to study the English language. Dr. Haws recorded that “…this royal household instruction was the first instance of providing formal education to women in the palace, and it may be considered the beginning of women’s education in Siam.”

An American female teacher taught Thai children, assisted by a Thai teacher.

Women in the missionary school during the reign of King Rama IV attended classes taught by Dr. Haws’s wife, who instructed them in literacy, sewing, and laundry skills.

In 1861 (B.E. 2404), King Mongkut graciously appointed Mrs. Anna Leonowens, a British national, to serve as an English teacher for his sons and daughters. He ordered the establishment of a school within the Grand Palace, where all royal children and members of the royal family could study the English language. Later, His Majesty extended the curriculum to include a broader range of academic subjects such as mathematics, science, astronomy, geography, and history. This initiative marked the foundational step toward a new model of modern education in Siam.

A line illustration of a schoolboy and schoolgirl in a Christian mission school.

The Emergence of Modern Schooling

The emergence of a structured school system in Siam marked a significant departure from traditional Thai education, which had long been centered in temples and royal courts. Unlike the older model, these new institutions featured defined curricula, fixed class schedules, and employed teachers for formal instruction.

King Mongkut (Rama IV) actively supported the establishment of schools by American missionaries as a means to educate the Thai people in Western languages, literature, and sciences. The American missionary community played a pivotal role in the early development of modern education in Thailand. Their schools, though still in their infancy, laid the groundwork for a systematic, internationally modeled education system. This represented a major step toward modern schooling, with structured teaching methods that would form the basis for later Thai education reforms.

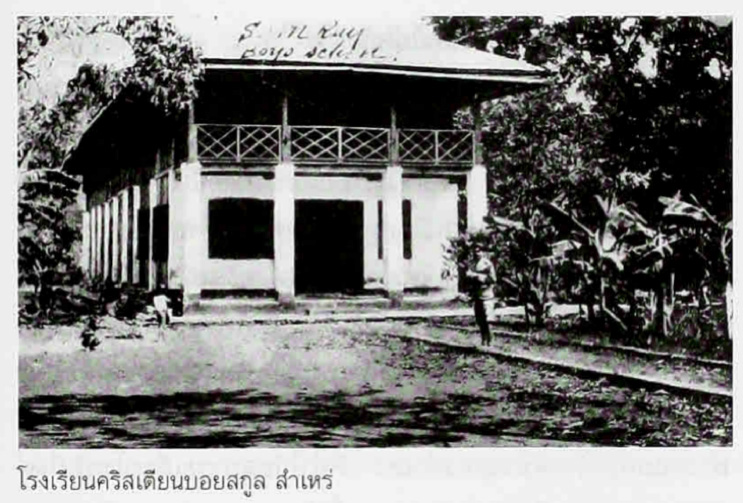

Bangkok Christian College, founded on September 13, 1852 (B.E. 2395), was among the earliest examples. It later merged with a school led by a Chinese Protestant teacher, Mr. Ki Eng Kuay Sian. The school admitted only male students, employed a Thai headmaster, and used the Thai language as the medium of instruction.

According to the records of Dr. Haws from August 1856, one passage reads: “Our school has expanded considerably. Many have come to enroll in English classes. The eldest son of the Chief Grand Minister attended Mrs. Mattoon’s class regularly. He was a bright child, seven years old. His Majesty requested that I personally teach two royal princes—one was his grandson, aged sixteen; the other, a grandson of the previous king, aged eleven. The King also ordered twelve boys, all sons of palace officials, to study English at our school as day students. As a result, we had to build a large bamboo schoolhouse at the back of our residence.”

The Christian Boys’ School at Kudi Chin was the first private school in Thailand.

Today, it is known as Bangkok Christian College.

As the school continued to grow, it was eventually relocated to a new site along the Chao Phraya River at the Samre district and became known as Samre Boys’ Christian High School. Later, the school moved again to the Silom area and was renamed Bangkok Christian College. It is recognized as the first school in Thailand and remains the country’s longest-standing educational institution to this day.

The first private school for female students in Thailand was established by American missionaries in Phetchaburi Province in 1865 (B.E. 2408). Today, it is known as Arunpradit School.

Arunpradit School was the first private school for female students in Thailand. It was established in Phetchaburi in April 1865 (B.E. 2408) by Mrs. S.G. McFarland, and was originally named Arun Satri School.

In its early years, the curriculum went beyond reading and writing; Mrs. McFarland also taught her students needlework and embroidery. When the first sewing machines were introduced to Thailand by missionaries, she incorporated them into her teaching, making it the first time machine sewing was taught in the country. As a result, Phetchaburi earned the nickname “Sewing Machine Town.” Arunpradit School came to be regarded as a school of handicrafts or industrial education, and is recognized as the first vocational school for women in Thailand specializing in garment making.

Overseas Education

In later years, interest in studying foreign languages and Western knowledge directly with missionaries became increasingly widespread, both among royalty and commoners. This growing enthusiasm likely stemmed from the expansion of international trade following the signing of the Bowring Treaty in 1855 (B.E. 2398). Contact with foreign merchants became far more extensive than before, aligning with the personal vision of King Mongkut (Rama IV), who favored individuals proficient in Western ways. His Majesty believed that those with intelligence and knowledge of the West should be invited to serve as advisors. Those fluent in English were often granted the opportunity to serve in positions close to the royal court.

This rising popularity in modern education led to an increase in Thai students being sent abroad. The first Thai students officially granted royal permission to study overseas accompanied the Siamese diplomatic mission to England in 1857 (B.E. 2400). There were two students: Mr. Thot Bunnag, son of Phraya Montri Suriwong (Chum Bunnag), and Mr. Thet Bunnag (later Chao Phraya Suraphan Phisut), son of Somdet Chao Phraya Borom Maha Prayurawong. Both students were entrusted to the British Foreign Office for enrollment in a royal college in London. However, for unknown reasons, both returned to Siam along with the diplomatic mission.

There were also three students who were sent abroad privately by their parents and later entered royal service under King Mongkut. These three individuals were recorded by Prince Damrong Rajanubhab:

Phraya Akkharatchawarathorn (Wad Bunnag), who served in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as Luang Wiset Pojanakan.

Phraya Akkharatchawarathorn (Net), who studied in Singapore and served as Khun Srisiyamkit, Assistant Siamese Consul in Singapore, and was later promoted to Luang Srisiyamkit, Vice Consul of Siam in Singapore.

Chao Phraya Phasakornwong (Phon Bunnag), who studied in England and held the position of Ratchanatyanuharn Humprae Wiset in the Royal Scribes Department. He was frequently entrusted with delivering royal commands abroad and served as Royal Secretary for English correspondence throughout the reign.

Chao Phraya Phasakornwong (Phon Bunnag)

Phraya Akkharatchanarat Phakdi (Wad Bunnag)

In addition, there were three other students who studied in Europe and later entered government service during the reign of King Chulalongkorn (Rama V):

Chao Phraya Surawong Watthanasak (To Bunnag), son of Chao Phraya Surawong Waiwat, studied artillery in England. He was the first Thai to complete formal military training in Europe.

Chao Phraya Ratchanupharap (Sutjai Bunnag), son of Chao Phraya Phanuwong Maha Kosathibodi (Thuam Bunnag), pursued his studies in England.

Luang Damrongsurinthararit (Bin Bunnag), son of Chao Phraya Surawong Waiwat, studied in France.

Chao Phraya Surawong Watthanasak (To Bunnag)

Chao Phraya Ratchanupharap (Sutjai Bunnag)

According to the records in Collected Writings of Prince Damrong Rajanubhab, there was a commoner who studied the English language and had the opportunity to accompany missionaries to the United States to pursue medical studies. He earned a medical certificate and returned to Siam, later entering royal service during the reign of King Chulalongkorn (Rama V). His name was Mr. Thien Hee, and he was appointed to government service under the noble title Phraya Sarasinswamiphak.

Phraya Sarasinswamiphak (Thien Hee Sarasin)

Educational Field Visit Abroad

In addition, King Mongkut (Rama IV) was deeply committed to modernizing the kingdom in line with civilized nations. In 1861 (B.E. 2404), he graciously appointed Chao Phraya Srisuriyawong and his son, Prince Wisanunatnipathorn, to observe British administrative and urban development practices in Singapore. His Majesty also sent officials abroad to study specific fields aligned with his modernization goals. For example, Khun Maha Sitthiworahan was sent to study printing technology, while Muen Chakrawijit was dispatched for training in clock repair.

His Royal Highness Prince Supradit, Prince Vishanunatnipathorn (Krom Muen Witsanunatnipathorn)

Somdet Chao Phraya Borom Maha Srisuriyawong (Chuang Bunnag)

It is evident that King Mongkut (Rama IV) strongly promoted Western-style education, both within the country and abroad. His efforts included sending students to study and undertake observation visits overseas. Some individuals sought knowledge from missionaries within Siam, while others accompanied missionaries abroad or were sent by their parents using private funds. Most of those who pursued education abroad eventually returned to serve in official positions during the reign of King Chulalongkorn (Rama V), contributing significantly to the kingdom’s modernization and administrative reform.

Support for Non-Formal Learning

In addition to formal education, King Mongkut (Rama IV) actively promoted the dissemination of modern knowledge to the general public in ways that were accessible and grounded in scientific principles. This effort played a crucial role in transforming the worldview of Siamese society, shifting it away from traditional beliefs toward a more rational, empirical understanding of the world. One of the key areas was science, particularly in explaining natural phenomena. His Majesty emphasized that occurrences such as droughts or heavy rainfall were not caused by deities or spirits, as traditionally believed, but rather by natural cycles related to geography and climate. He advised the people to store water during the rainy season and to begin rice cultivation early to ensure food security and surplus income for the dry season.

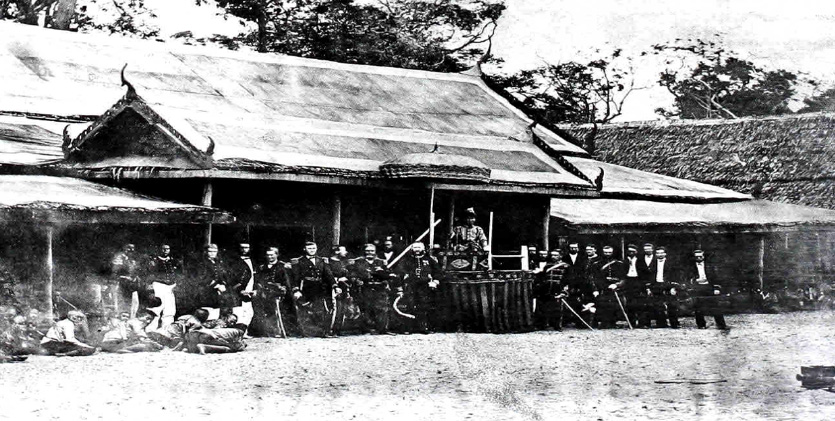

Furthermore, the King helped demystify astronomical events such as solar eclipses, explaining them as results of the orbital movements of the Earth, Sun, and Moon—not as manifestations of superstition. This scientific approach culminated in his accurate prediction of the total solar eclipse at Wako (Wagor), Prachuap Khiri Khan Province in 1868, which marked a significant milestone in Siam’s intellectual and scientific advancement.

King Mongkut (Rama IV) was seated at the front terrace of the royal pavilion and graciously allowed a photograph to be taken with foreign dignitaries at the royal encampment in Ban Wa Ko.

This approach proved effective in transforming traditional Thai beliefs and attitudes, while simultaneously introducing modern scientific knowledge. It laid an important foundation for the development of science education based on academic principles in Thai society in the years that followed.

The first printing press brought into Siam by Dr. Bradley

In addition to the aforementioned students, there were three others who pursued their studies in Europe and later entered government service during the reign of King Chulalongkorn (Rama V). Chao Phraya Surawong Watthanasak (To Bunnag), son of Chao Phraya Surawong Waiwat, studied artillery in England and became the first Thai to complete formal military education in Europe. Chao Phraya Ratchanupharap (Sutjai Bunnag), son of Chao Phraya Phanuwong Maha Kosathibodi (Thuam Bunnag), also studied in England. Meanwhile, Luang Damrongsurinthararit (Bin Bunnag), another son of Chao Phraya Surawong Waiwat, received his education in France. These individuals represented a new generation of Western-educated elites who contributed to the modernization of Siamese administration and military affairs.

In 1847 (B.E. 2390), the Bangkok Calendar published by Dr. Bradley noted that “…the printing house of Prince Mongkut possessed one printing press, one set of Thai type, two sets of English type, and two sets of Pali type. Most of the printed works were in the Pali language,” and it further stated that this was considered the first printing press established by a Thai.

บทสวดมนต์ตัวอักษรอริยกะ มงคลสูตร

In 1851 (B.E. 2394), upon ascending the throne, King Mongkut (Rama IV) commissioned the establishment of another printing house within the Inner Court of the Grand Palace. This two-storey building was named Aksorn Pimphakarn Press. It served as the first official royal printing house—effectively the national press of Siam. In 1861 (B.E. 2401), the press published the Ratchakitchanubeksa (Royal Gazette), the kingdom’s first official government publication, intended to disseminate royal court news and government proclamations.

Dr. Bradley’s printing press was not restricted or marginalized; on the contrary, he was revered as the “father of all printing houses” in Siam. He was granted the first royal copyright in Thai history, allowing him to publish Thai language textbooks such as Jindamanee, Prathom Kor Kai, Prathommala, as well as textbooks in practical subjects like engineering and Western medicine for public distribution.

The introduction of printing technology to Siam marked a major turning point in the dissemination of knowledge to the public. It initiated a shift from oral traditions (mukhapatha) to written, printed communication. This transition enabled knowledge—once confined to the royal court and government officials—to reach a much broader public audience. It reflected a fusion between traditional Thai education and Western missionary knowledge, accelerating the development of modern education in the country. The Thai textbooks developed and printed by Dr. Bradley’s press were likely also used in the missionary schools for teaching the Thai language.

It can be said that King Mongkut’s (Rama IV) acceptance of English education and Western civilization marked the beginning of a significant transformation in the country’s educational development. The traditional system of education, which had been passed down for centuries, began to gradually shift toward a new direction. Although initially limited to the nobility and high-ranking officials, sending individuals abroad to study modern knowledge laid the foundation for long-term national development. It set the stage for a future in which government functions would diversify and increasingly require specialists with technical and academic expertise.

Despite being burdened with numerous responsibilities and facing a precarious national situation during the height of colonial expansion, King Mongkut successfully resisted the tide of imperialism. He initiated critical reforms and laid the groundwork for national progress. However, his reign lasted only 17 years, during which he had to devote considerable time to self-education in modern sciences. At the same time, the general populace remained largely uneducated and unprepared for rapid change. Even so, the King persistently sought to build the foundations of modern education, persuading the public to embrace rational thinking and scientific knowledge. Many of his educational efforts bore fruit in the reign of his son, King Chulalongkorn (Rama V), who continued and expanded upon these reforms.

Bibliography

Khon Chin 200 Pi Phai Tai Phra Borommaphotisomphorn [Chinese People Under Royal Patronage for 200 Years]. Bangkok: Senthang Setthakit, 1983.

Chulachakrabongse, H.R.H. Prince. Chao Chiwit [The Living Lord]. 4th ed. Bangkok: Khlang Witthaya, 1974.

Chomrom Damrongwitthaya nai Uppatham Mom Chao Phunphitsamai Diskul. Phra Bat Somdet Phra Chom Klao Chao Yu Hua [King Mongkut]. Bangkok: Bandit Kanphim, 1984.

Chonphum Banhan. Khwam Thansamai Thang Kanmueang Tam Naeo Phra Ratchadamri nai Phra Bat Somdet Phra Chom Klao Chao Yu Hua [Political Modernization under King Mongkut’s Vision]. Bangkok: M.A. Thesis in History, Srinakharinwirot University, 2009.

Chaophraya Thiphakorawong (Kham Bunnak). Nangsue Saeng Kitjanukit [Account of Duties and Events]. Bangkok: Kurusapha, 1971.

Commemorative Book for the Inauguration of the Queen Debsirindra Monument in the Reign of King Rama IV. Bangkok: Debsirin School, 1998.

Burusat Chanai: Ong Nueng Khong Chat Thai [The Ideal Gentleman: A Pillar of the Thai Nation]. Phra Nakhon: Mahamakut Royal College Press, 1949.

Naruemon Thirawat. Phra Ratchadamri Thang Kanmueang Khong Phra Bat Somdet Phra Chom Klao Chao Yu Hua [Political Philosophy of King Mongkut]. Bangkok: M.A. Thesis in History, Chulalongkorn University, 1982.

Bradley, William E. Siam Samsamai Chak Saita Mo Bradley [Siam Through the Eyes of Dr. Bradley in Three Eras]. Bangkok: Phuean Chiwit, 1984.

Praphat Trinarong. Phra Prawat lae Phonngan Somdet Krom Phraya Damrong Rajanupap [Biography and Works of Prince Damrong Rajanupap]. 3rd ed. Bangkok: Damrongwitthaya, 2003.

Pramin Khruathong. Phra Chom Klao “King Mongkut”: Phra Chao Krung Siam [King Mongkut of Siam]. Bangkok: Matichon, 2004.

Phra Bida Haeng Witthayasat Thai: 18 August 2004 [Father of Thai Science]. Bangkok: Office of the Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Science and Technology, 2004.

Phra Bowon Ratchanuson: King Pinklao [Royal Tribute to King Pinklao]. Bangkok: Chanwanich, 2010.

Dr. Preecha and Prapai Amatayakul Foundation. Chaloem Phra Kiat Phra Bida Haeng Witthayasat Thai [In Honor of the Father of Thai Science]. Bangkok: Amarin Printing and Publishing, 1998.

Wachirayan Warorot, Somdet Phra Maha Samanachao Krom Phraya. Phra Prawat Trut Lao [Autobiography as Told by the Author]. 3rd ed. Phra Nakhon: Mahamakut Royal College Press, 1964.

Somsri Bunarunraksa. Phra Sangharat Pallegoix: Mit Thi Di, Sanit Sanom lae Chingchai nai Ratchakan Thi 4 [Bishop Pallegoix: A Trusted and True Friend in King Rama IV’s Court]. Bangkok: Catholic Media of Thailand, 2007.

Samutphap Chotmaihet Ngan Chaloem Phra Kiat Phra Bat Somdet Phra Chom Klao Chao Yu Hua nai Okat Wan Chaloem Phra Ratchasomphot 200 Pi [Pictorial Archives Commemorating the 200th Birth Anniversary of King Mongkut]. Bangkok: Amarin Printing and Publishing, 2005.

Somrat Charulaksananon. “Nai Phaet House: First Anesthesiologist in Siam.” Wisan Yisan [Anesthesia Journal] 37, no. 1 (January–March 2011): 1–4.

Suwichai Kosaiyawawat. “Development of Royal Education Before the Reforms of King Rama V: The Foundations of Formal and Modern Thai Education.” Journal of Education, 17, no. 2 (Nov 2005–Mar 2006): 1–17.

Suwichai Kosaiyawawat. “National Development during King Rama IV’s Reign: Laying the Foundation for Siam’s Transition from a Traditional to a Modern Society.” Journal of Education, 16, no. 1 (June–October 2004): 29–48.

Sethuean Supasopon. Prawat Kan Rongrian Rat nai Prathet Thai lae Thamniap Rongrian Rat [History of Private Schools in Thailand and School Directory]. 2nd ed. Phra Nakhon: Association of Private School Teachers of Thailand, 1971.

Hetkan Ton Ton Ratchakan Thi 4 [Early Events in the Reign of King Rama IV]. Phra Nakhon: Sophon Piphatthanakon Press, 1932.

Opas Sawikoon. Phra Ratcha Bida Haeng Kan Patirup [Father of Thai Reform]. Phra Nakhon: Phrae Phitthaya, 1970.