The King Mongkut Studies Initiative

Social and Cultural Transformation in Siam

The Social and Cultural Transformation of Siam During the Reign of King Mongkut

HRH Prince Damrong Rajanubhab recorded that: “…In the reign of King Nangklao (Rama III), there were five Siamese individuals who acquired Western knowledge from American missionaries with great distinction. They were: His Majesty King Mongkut, who studied languages during His monkhood; His Majesty King Pinklao, who studied military science;

Prince Wongsathiratsanit, who studied medicine; Somdet Chao Phraya Borom Maha Sri Suriyawongse, who—when still known as Luang Nai Sit—studied the craft of shipbuilding; and Mr. Mot Amatyakul, who studied mechanical engineering…”

(Source: 200 Years of HRH Prince Wongsathiratsanit, 2008, p. 28)

Somdet Chao Phraya Borom Maha Sri Suriyawongse (Chuang Bunnag) (B.E. 2351–2425)

Image source: Historical Images of the Reign of King Mongkut.

Bangkok: Fine Arts Department, 2005, p. 152.

Prince Supradit (Phra Chao Borommawong Thoe Krom Muen Wisanunat Nipathon), born to Chao Chom Manda Noi, founder of the Supradit family (B.E. 2367–2405).

Image source: Historical Images of the Reign of King Mongkut.

Bangkok: Fine Arts Department, 2005, p. 152.

When King Mongkut (Rama IV) ascended the throne, he supported the preparation of capable individuals to become the driving force behind future national development. He promoted education for his sons and daughters and expanded learning opportunities to nobles and commoners alike—particularly in foreign languages to broaden perspectives and enable learning of modern sciences and technologies from abroad. These included physics, chemistry, electroplating with silver and gold, navigation, Western medicine, coin minting, printing, communications, military science, agriculture, photography, engineering (e.g., road construction), among others. He also sent personnel to study abroad. For instance, he ordered Somdet Chao Phraya Borom Maha Sri Suriyawong and Prince Wisanunat Nipathon to observe governance and urban development in Singapore in 1860 (B.E. 2402) (Naengnoi Saksri, 1994, p. 216).

King Mongkut foresaw that Siam was facing increasing pressure and influence from all directions, which would affect national security, the economy, daily life, society, and traditional culture. Therefore, he implemented social reforms such as abolishing the tradition of bare-chested court audiences, allowing foreign merchants to participate in royal assemblies, letting commoners greet the King with offerings and decorations in front of their homes, permitting them to submit petitions directly to him, and allowing foreigners to greet him by handshake or standing to show respect (Sombat Plainoi, 1984, pp. 29–30; Somsri Boon-arunraksa, 2007, pp. 87, 91).

These changes and administrative reforms stemmed from the King’s royal address:

“Since Siam is being encroached upon by France on one side and by British colonies on the other… we must decide what to do: swim upstream to befriend crocodiles, or swim into the sea and cling to whales. Even if we discover a gold mine that could buy hundreds of warships, we would not be able to fight these powers, as we would be buying the ships from them. They could stop selling to us at any time… The only weapon truly beneficial to us in the future is speech and a heart endowed with reason and wisdom.” (Nawaporn Ruangsakul, 2007, p. 10).

This led to the signing of the Bowring Treaty in 1855 (B.E. 2398) with Britain and later with other Western nations. Although the treaty put Siam at a disadvantage, the King recognized the necessity of compliance to avoid armed coercion by British gunboat diplomacy—used effectively in China—and feared that resistance might lead to Siam becoming a colony, as had happened to neighboring countries (Krairerk Nana, 2007).

In parallel with these diplomatic efforts, the King worked to modernize Siam to prevent Western powers from claiming the country was barbaric and uncivilized—a common justification under the so-called “White Man’s Burden” to colonize and “civilize” Asian and African nations. This modernization helped deter colonial occupation and fostered lasting social and cultural transformation.

The phenomenon of a hundred cargo ships crowding the Chao Phraya River in late 1864 (B.E. 2407) reflects the vibrant expansion of international trade and modernization of Siam during the reign of King Mongkut (Rama IV). This image, drawn from: Source: Phiphat Phongrapeephorn, A Panoramic View of Bangkok in the Reign of King Rama IV: A New Discovery, Bangkok: Muang Boran, 2001, p. 100.

Sitthikarn Mint, established by King Rama IV, where a machine-operated coin factory was built in front of the Royal Treasury.

(Source: Prachum Phap Prawattisat Phaendin Somdet Phra Chom Klao Chao Yu Hua. Bangkok: Fine Arts Department, 2005. p. 38.)

Economic

Sir John Bowring negotiated the Bowring Treaty (1855 CE or 2398 BE), which marked the first official opening of Siam to international trade. This treaty is widely regarded as the origin of modern Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), which are economic blocs aiming to reduce tariffs among member countries.

As a result of the treaty, Siam was required to abolish the royal trade monopoly system known as Phra Khlang Sinkha, in which the economy was centralized under the king and operated through ministers who auctioned off tax collection rights and delivered expected revenues to the royal treasury, keeping any surplus for themselves. The treaty ended this system entirely.

Furthermore, the traditional ber rong (harbor fee) or pak ruea (entry tax) was eliminated. A new Customs House (Sunkasathan) was established to collect a 3% import duty and specified export duties listed in the treaty annex. This introduced a new customs regime in Thailand, which has been in place ever since.

Importantly, the treaty had no expiration date—it could only be amended by mutual consent of both parties.

(Sources: Kraisak Nana, 2007; Nawaporn Ruangsakul, 2007, pp. 10–11)

Finance Sector

Trade between Thailand and foreign countries rapidly flourished following the signing of the Bowring Treaty. This led to an influx of foreign currencies and silver bullion into the country, resulting in a trade surplus. As trade expanded, the demand for currency as a medium of exchange increased. The handmade bullet coins (pod duang) were no longer sufficient for circulation. His Majesty resolved this issue through several measures: In 1857 (B.E. 2400), he issued a decree allowing the use of foreign currencies—such as the Mexican dollar and coins from the Straits Settlements (territories under the British East India Company in Southeast Asia, including Penang, Singapore, and Malacca)—to legally settle debts. Royal stipends were paid in Mexican coins (Nawaporn Ruangsakul, 2007, pp. 10–11). In 1860 (B.E. 2403), His Majesty ordered the establishment of the Sitthikarn Mint inside the Grand Palace to produce machine-struck coins in various denominations made of gold, silver, copper, and tin (Department of Mineral Resources, 2008, pp. 71–72).

Communication

Sompong Kriangkraiphet (1965), Opas Sawikoon (1970), and Sanguan Ankong (1959) note that while King Mongkut (Rama IV) was still ordained at Wat Bowonniwet, he recognized the importance of printing for disseminating Buddhist teachings. He therefore ordered a printing press to be used for printing Buddhist texts. Upon ascending the throne, he established the Royal Press (also known as the Aksorn Pim Kan Printing House) and oversaw the casting of Thai typefaces for printing.

Initially, he commanded the publication of a news bulletin titled Ratchakitjanubeksa (Royal Gazette), first issued in 1861 (B.E. 2401) on a biweekly basis. Later, he ordered the printing of royal proclamations and full documents. Historical records indicate that during his reign, five newspapers were circulated—one in Thai and four in English—to disseminate news and information.

Prince Akson Sasanon Sophon was known to have read The Illustrated London News, indicating that English newspapers had made their way into the royal court of Siam. This demonstrates the Thai monarchy’s openness to international perspectives and news media during the reign of King Mongkut.

Image Source: Kraisri Nara. “Siam Regained Its Independence: National Solutions Through Royal Strategy.” Bangkok: Matichon, 2007, p. 5.

The Illustrated London News, 5 December 1857 Edition:

(Interior News Image) The first diplomatic mission from the Kingdom of Rattanakosin to the United Kingdom consisted of 28 members, including envoys and attendants. The delegation was led by Phra Montri Suriwongse (Chum Bunnag), who traveled by ship and arrived in Portsmouth, England, on 28 October 1857. The mission presented the royal letter from King Mongkut (Rama IV) to Her Majesty Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle on 19 November 1857.

Image Source: Kraisri Nara. The Illustrated Album of King Rama IV: Crisis and Opportunity of Rattanakosin in 150 Years. Bangkok: Matichon, 2007, p. 60.

Kraisri Nara (2007) noted that King Mongkut actively followed international developments. This is evident in a royal letter sent to Chao Phraya Montri Suriwongse (Chum Bunnag), the envoy to England, where the King wrote:

“…You’ve been gone for many months. I have had to follow news from the foreign newspapers (The Illustrated London News)…”

—indicating that the King subscribed to the publication to stay informed.

Additionally, Sir John Bowring brought the inscription of King Ramkhamhaeng—discovered by King Mongkut—to be published in England in 1857 (B.E. 2400). It was later published in Germany by Mr. Bastian in 1865 (B.E. 2408), and in France by Mr. Fournereau in 1891 (B.E. 2434) (Sompong Kriengkraipetch, 1967, p. 195).

Another notable milestone was when Dr. Bradley purchased the publishing rights to Nirat London, written by Mom Rajawongse Karta Isarangkun (M.R. Rachothai), for 400 baht. This marked the first known copyright transaction in Thai literary history. The book was first published in 1861 (B.E. 2404, the Year of the Rooster) (Opas Sawikoon, 1970, p. 165).

Postage stamps from India and the Straits Settlements were used by the British Consulate in Siam, overprinted with the letter “B” to denote Bangkok.

Source: Thailand Post Co., Ltd. (2008). 125 Years of Thai Postal Service. Bangkok: Thailand Post, p. 30.

Sir John Bowring (known in Thai as Phra Ya Siammanukulkij Siammitmahayot, 2335–2415 B.E. / 1792–1872 CE)

Image source: “Prachum Phap Prawattisat Pandin Somdet Phra Chom Klao Chao Yu Hua” (Collection of Historical Images from the Reign of King Mongkut), Bangkok: Fine Arts Department, 2005, p. 167.

In 1867 (B.E. 2410), the British Consulate introduced a postal system to facilitate correspondence between Bangkok and Singapore. This development was prompted by the growing presence of Western residents in Siam and the establishment of consulates in Bangkok to oversee their nationals and commercial activities. Consequently, commercial communication between Siam and foreign countries significantly increased. Initially, Indian postage stamps were used for mail payment. Later, stamps from the Straits Settlements and Hong Kong were adopted, overprinted with the letter “B” to represent Bangkok, and affixed to postal items. Additionally, some mail was sent via private shipping companies without passing through the British consular post office in Bangkok.

Prince Damrong Rajanubhab recounted in his memoirs: “…International mail between Siam and foreign countries had to rely on the British Consulate… to forward it to the Singapore or Hong Kong postal departments… But for government correspondence, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs would entrust naval officers to deliver the mail directly to the Siamese Consulate in Singapore…” (Thailand Post Co., Ltd., 2008, pp. 28–30)

Foreign Affairs

King Mongkut appointed a Western diplomat—Sir John Bowring, who had formerly served as Her Majesty’s Plenipotentiary Ambassador from Great Britain and had been the first to formally negotiate with Siam during his reign—as Plenipotentiary Minister and Ambassador Extraordinary representing Siam. By royal decree, issued on June 3, 1867 (B.E. 2410), Sir John Bowring was officially appointed to this prestigious post on behalf of Siam. Later, on August 30, 1867, His Majesty graciously conferred upon Bowring the Siamese noble title: Phra Sayan Anukulkij Siammitmahayot.

Subsequently, on March 27, 1868 (B.E. 2411), the King ordered two seals to be prepared and presented to him—both identical, one larger for stamping official documents, and the other smaller for sealing with lacquer. These seals featured the Great Crown of Victory (Phra Maha Mongkut) at the top, beneath which stood an image of an elephant on a pedestal. Below the pedestal appeared the Latin inscription:

“Legatus Regius Negotiorum Regni Siamensis”

(meaning “Royal Envoy for the Affairs of the Kingdom of Siam”).

In addition to Sir John Bowring, Mr. Edward Fowle was also appointed by the King. According to Anek Nawigamune (2006, pp. 67–83), Mr. Fowle—who had formerly accompanied the Thai royal delegation to England—was appointed Luang Siam Anukhro (Consul of Siam) in Rangoon in 1863 (B.E. 2406). His responsibility was to liaise with British Burma and the King of Ava regarding matters of interest to Siam.

Later, Luang Siam Anukhro sent a letter to the King requesting permission to construct a pavilion near the Shwedagon Pagoda in Rangoon to serve as a shelter for Siamese pilgrims visiting the sacred site. Upon receiving this request, the King ordered a formal letter to the British authorities asking for land approval. Once granted, the King personally funded the construction of the pavilion as proposed.

Agriculture

After the signing of the Bowring Treaty, agricultural cultivation—especially rice farming—expanded extensively, particularly in the Central Region, due to the increasing global demand for rice. The development of efficient maritime transport facilitated this expansion, transforming agriculture from a subsistence-based system into commercial production for export. Consequently, the economic system shifted from a monopolistic model to a free trade system. The king encouraged wage labor and attempted to reduce the number of corvée laborers by minimizing the practice of body tattooing for conscription purposes.

Chulaladda Phakdiphumin (2008: 181–185) noted that during the reign of King Rama IV, foreign flower seeds such as dahlias and gladiolus were imported for cultivation.

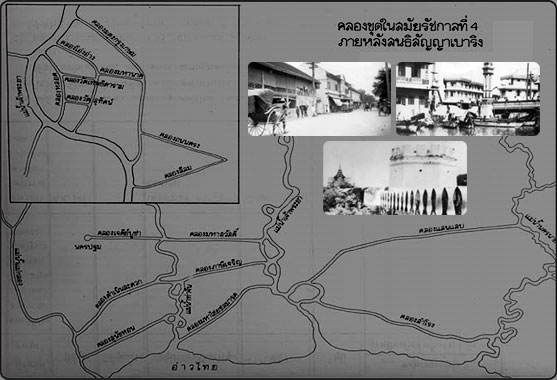

Map showing the excavated canal (Khlong Phadung Krung Kasem), Charoen Krung Road, and Fort Ritthirut Roraman located near the southern side of Phra Thinang Sutthaisawan.

(Photo taken during the reign of King Rama V)

Image source: Prachum Phap Prawattisat Phaendin Somdet Phra Chom Klao Chao Yu Hua [Collection of Historical Images of the Reign of King Mongkut].

Bangkok: Fine Arts Department, 2005, pp. 125–129.

Public Infrastructure

In the matter of road construction, His Majesty King Mongkut graciously commanded the development of key thoroughfares in the capital, including Charoen Krung Road, Bamrung Muang Road, and Fueang Nakhon Road. Additionally, major canals were excavated to enhance waterborne transport and urban drainage, notably the Phadung Krung Kasem Canal, Wat Traimit Canal, Si Lom Canal, Wat Sutharam Canal, Khlong Khwang, and the Mahasawat Canal.

As for bridges, Chulalada Phakdiphumin (2002) recorded that in the early days—prior to and during the early years of King Mongkut’s reign—the bridges crossing the inner-city canals (notably Khlong Bang Lamphu–Ong Ang, dug in the reign of King Rama I), and those spanning the Phadung Krung Kasem Canal (an outer moat canal dug in 1852, during the reign of Rama IV), were constructed entirely of wood.

It was not until the year 1861 (2404 B.E.) that the first iron bridges were built in the kingdom. Two were constructed:

An iron swing bridge over Khlong Bang Lamphu–Ong Ang, connecting Charoen Krung Road from within to outside the old city walls. This bridge was of a swing type that could be opened and closed, allowing for the royal processional barges to pass during ceremonial events.

Another bridge was built to replace the original “Saphan Han” (the Turning Bridge), which had formerly been a wooden drawbridge. This, too, was reconstructed as an iron swing bridge of similar design.

These developments were undertaken not only to improve the convenience of transportation and commerce within the growing city, but also to accommodate the preferences and expectations of the increasing population of Western expatriates and merchants residing in Bangkok.

The fire hose cylinder, crafted from brass, possessed a diameter of 1.8 inches and a length of 1.33 meters, which could be extended to a full 2 meters. It was capable of discharging water over a horizontal distance of 50 to 60 meters, with a vertical reach high enough to strike the roof of a three-storey building.

Image from : URL : http://i176.photobucket.com/albums/w176/mrtbtt/35.jpg

In matters of fire prevention, His Majesty issued a royal letter instructing the Siamese envoy, who had been dispatched to establish amicable relations with Great Britain, to procure modern firefighting apparatus for use within the Grand Palace compound (Paothong Thongchua, 2007). As for public health, the King proclaimed a prohibition against the populace discarding animal carcasses into waterways, recognizing that unclean water was a principal cause of various diseases. He further admonished the people to exercise caution regarding fire hazards, especially those arising from household hearths, and recommended that hearths be constructed using bricks and mortar for greater safety (Kanokwan Chuchaiya, 2004, p. 64).

During the excavation of the Maha Sawat Canal, with Chao Phraya Thipakorn Wong serving as the chief commissioner, rest pavilions were erected along the canal bank at intervals of approximately one hundred sen per pavilion. At each of these stations, medicinal texts detailing remedies for various ailments were posted for the public benefit. The people thus came to refer to such pavilions as “Sala Ya” or “Medicine Pavilions.” Additionally, another pavilion was constructed specifically as a site for the performance of posthumous merit-making rites on behalf of the commissioner himself, and was called “Sala Tham Sop” or “Funeral Pavilion” (Somphong Kriengkraipetch, 1965, pp. 178–179).

With regard to the advancement of modern medicine, His Majesty graciously permitted Dr. Dan Beach Bradley and Dr. House to provide treatment using Western medicine, including the crafting of artificial teeth for royal use (King Mongkut University of Technology Thonburi Archives, 2005; Prayut Sitthiphan, 1973, pp. 158–162). It is also recorded that Bishop Pallegoix ordered Semen Contra, a medicinal preparation, for use in the manufacture of lozenges to be distributed to children for the treatment of intestinal parasites (Somsri Boonarunraksa, 2007, p. 175).

tourism and hospitality

In the realm of tourism and hospitality, according to the course on Principles of Hotel Management offered by Mahasarakham Rajabhat University, it is stated that: “The hotel business in Thailand first emerged during the reign of King Mongkut (Rama IV). Three notable establishments were in operation—namely the Union Hotel, Fishers Hotel, and the Oriental Hotel. The majority of patrons were foreigners who had traveled to the Kingdom.” It was later recorded that both Fishers Hotel and Oriental Hotel succumbed to fire, after which a seaside resort hotel was constructed at Ang Sila, in Chonburi Province, specifically to accommodate foreign visitors seeking sea air and convalescence.

This account aligns with the writings of Ekachart Jan-urairot (2008, pp. 86–87) and Paothong Thongchua (2006, p. 24), who noted: “…The very first seaside health resort in Thailand was established during the reign of King Rama IV, following a request from foreigners for permission to build such a facility in Ang Hin, Chonburi.” Moreover, in the year 1861 (B.E. 2404), Bishop Pallegoix journeyed to Chanthaburi for the purposes of seaside recuperation and treatment of an eye condition, where he stayed for a duration of one month (Somsri Boonarunraksa, 2007, p. 179).

His Majesty King Mongkut (Rama IV) and Her Majesty Queen Debsirindra,

photographed in the year 1856 (B.E. 2399).

Source: “Collection of Historical Photographs of the Reign of King Mongkut.”

Bangkok: Fine Arts Department, 2005, p. 33.

Her Majesty Queen Mother Phiyamavadi Sri Patcharindra Mata

(Chao Khun Chom Manda Piam)

(1829–1904, B.E. 2382–2447)

Source: “Collection of Historical Photographs of the Reign of King Mongkut.”

Bangkok: Fine Arts Department, 2005, p. 38.

In the early period of photography in Siam, Prince Damrong Rajanubhab once explained, “…when photographers first arrived, there were few who agreed to be photographed.” However, in later times, His Majesty King Mongkut (Rama IV) graciously commissioned photographers to take a royal portrait of Himself together with Her Majesty Queen Debsirindra, and had the image sent to Queen Victoria of England, Napoleon III of France, and the President of the United States, along with royal gifts. (These offerings are now preserved in Windsor Castle in England, the Palace of Fontainebleau in France, and institutions in the United States.) These three nations were, at the time, experiencing diplomatic friction with Siam, and thus this gesture may be regarded as an early form of royal diplomatic strategy initiated by King Mongkut. Moreover, the King also graciously commanded that photographs be taken of Chao Khun Chom Manda Piam and Chao Khun Chom Manda Sumalee, royal ladies of the Inner Court, dressed in Western-style gowns, and had these images sent abroad as well. This served to illustrate that Siam had embraced Western culture, and allowed people on the far side of the world to see the appearance of the Siamese and the modernizing atmosphere of the Kingdom, which had begun to incorporate science into daily life—evident in photography, image processing, and the publication of those images in foreign newspapers. (Krairik Nanah, 2007)

As for royal hospitality, Opas Sawikkul (1970, pp. 111, 165) noted that “…on the occasion of the royal visit to Wako for the observation of a solar eclipse… the food served at the banquet was prepared by a French chef, and the head steward, an Italian, poured wine or champagne, considered at the time a luxury of great rarity, chilled in ice to perfection… and His Majesty graciously permitted ladies of the Inner Court as well as royal sons and daughters to attend the banquet.”

Military and Police Affairs

According to Opas Sawikkul (1970, pp. 276–282) and Suwan Petchnin (2004, p. 97), His Majesty King Mongkut (Rama IV) not only commanded the excavation of Khlong Phadung Krung Kasem to improve transportation and expand arable land, but also to serve as an outer defensive moat to protect the capital from potential enemies. Upon the canal’s completion, His Majesty appointed Chao Phraya Sri Suriwongse as chief commissioner to construct a series of forts along this outer line of defense. These included Fort Defier of Foes, Fort Shutter of Enemies, Fort Bold and Fearless, Fort Slayer of Foes, Fort Vanquisher of Enemies, Fort Breaker of Opposition, Fort Crusher of Rebels, and Fort Defender of the Metropolis.

In the early years of His reign, King Mongkut further ordered the restructuring of the military, introducing Western-style military training and establishing regiments modeled after European forces. These included an Infantry Regiment, an Artillery Regiment, and a unit of Marines. The King also commissioned the construction of numerous sailing vessels for both military and commercial purposes. With the later arrival of steam-powered ships, His Majesty ordered the building of the Siam Orasumphol, the Kingdom’s first steam warship, equipped with naval officers and gunners following the traditions of the British Royal Navy. Other vessels such as the Siam Upsadum and the Pirate-Chaser were also constructed to defend the nation’s sovereignty.

According to the Royal Thai Police Office (2008, pp. 1–21), Lumjul Huabcharoen (2007, p. 280), and Chutarat Ueanamnuay et al. (2008, pp. 104–111), His Majesty King Mongkut recognized the pressing need to reform the kingdom’s policing system, driven by the growing threat of crime, social unrest, and pressure from foreign powers, particularly Britain and France, over issues of extraterritoriality. This provision exempted nationals from Britain, France, the United States, Denmark, Portugal, and others from Thai legal jurisdiction—creating serious disruptions to the administration of justice in Siam.

In response, His Majesty initiated reforms inspired by police systems in Singapore and British India, and in 1860 (B.E. 2403), appointed Captain Samuel Joseph Bird Ames, a British officer, to organize a formal police force. This unit, known as the Police Constables, was comprised primarily of Malay and Indian recruits and tasked with maintaining order in the capital. It was placed under the jurisdiction of the Royal Capital Police Bureau, marking the beginning of a modern, centralized police force in Siam.

It may be said that the aforementioned reforms—military, infrastructural, and legal—were integral in enabling Siam to withstand the threat of colonial encroachment during the height of Western imperialism. Through King Mongkut’s astute diplomacy and strategic modernization, Siam succeeded in asserting its sovereignty and earning the respect of the Western powers, positioning itself as a civilized nation among empires.