The King Mongkut Studies Initiative

Siam Opens Its Doors to Trade in the Reign of King Rama IV: The Economic Foundations of National Development

Compiled and edited by Ms. Sompong Yimlamai and Ms. Supap Klinrueang

His Majesty King Mongkut (Rama IV) was a monarch of the Rattanakosin Kingdom who pursued a remarkably open and far-reaching policy of engagement with Western nations. He is widely regarded as the “prototype” for Siam’s modern foreign policy. During the 27 years in which he lived as a Buddhist monk prior to ascending the throne, the King remained acutely attentive to global affairs, particularly the movements and ambitions of Western powers. Motivated by deep concern for the future of the nation, His Majesty recognized that the time had come for the Siamese people to begin earnestly studying the Western world—its peoples, its systems, and its material progress—so as to prepare the Kingdom for the profound changes that loomed on the horizon.

These concerns stemmed from mounting global shifts, including the Industrial Revolution in Europe and the aggressive expansion of Western imperialism, as major powers vied for colonial dominion through military and technological superiority. Such imperial competition had already begun to impact the region by the reign of King Rama III, when Britain defeated Burma, China, and several Malay principalities, asserting itself as a dominant force in Southeast Asia.

The Industrial Revolution in Europe

During the 18th and 19th centuries, the Industrial Revolution, which began in Great Britain and soon spread to other European nations, marked a dramatic transformation in global economic systems. As industrial production advanced, output soon exceeded the level of domestic consumption. This led to a pressing need for new markets to absorb surplus goods, thereby fueling a fierce competition among Western powers to expand their influence across various regions of the world.

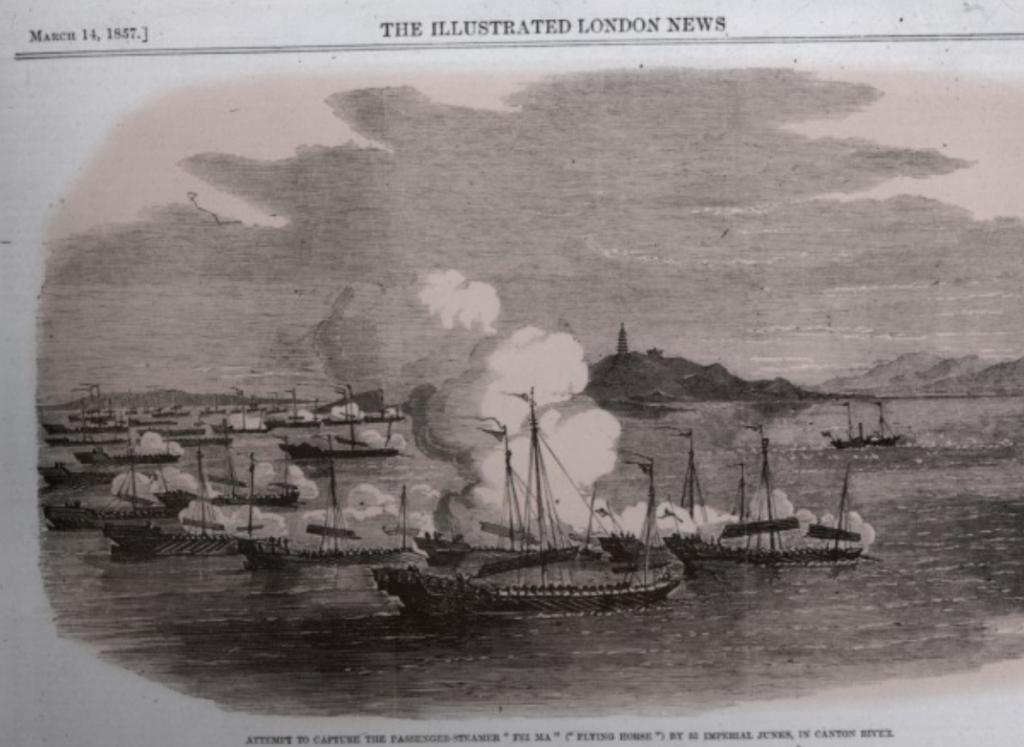

At that time, many nations in Asia—including Siam (Thailand)—found themselves increasingly under pressure from Western imperial ambitions. The case of China, one of Asia’s largest and most powerful empires, served as a stark example. China’s refusal to engage in open trade and its persistent resistance to diplomatic relations with the West culminated in serious consequences. Most notably, the Opium War (1840–1842), in which China was decisively defeated by Britain, highlighted the dangers of isolationism in the face of aggressive Western expansion.

Simultaneously, Britain and France were vying for strategic footholds in Burma and Indochina, seeking routes and staging grounds for deeper penetration into Yunnan and Tibet. These geopolitical maneuvers underscored the growing reach of European empires and the vulnerability of Asian polities during this critical period of imperial contestation.

The Industrial Revolution

The Opium Wars in China

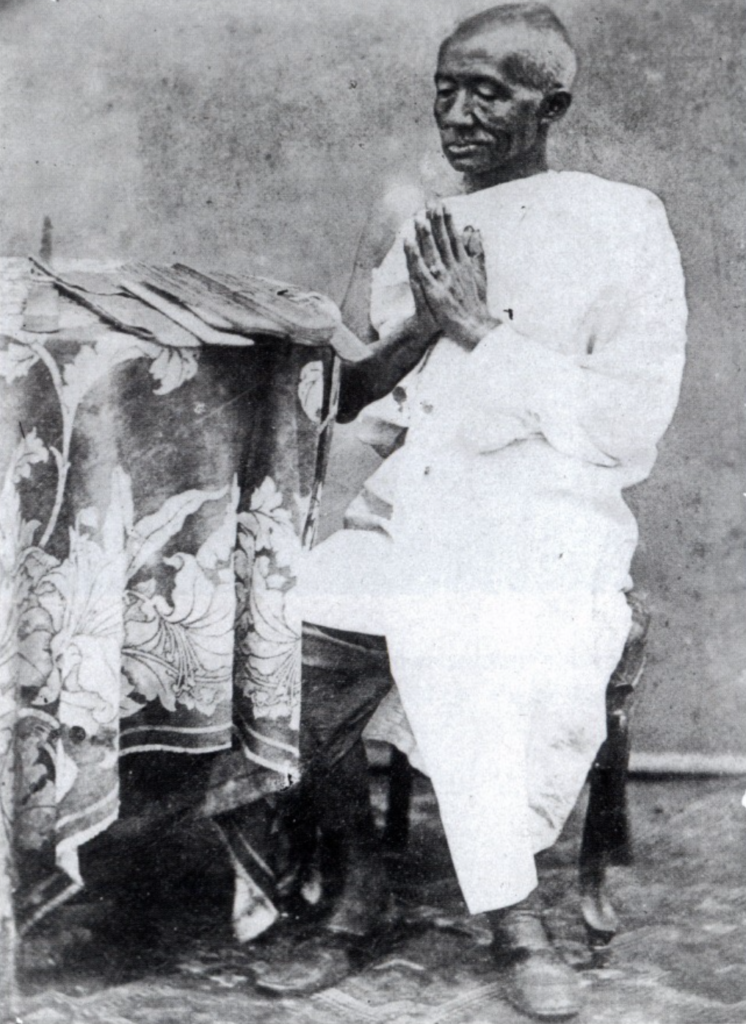

The Reign of His Majesty King Mongkut (Rama IV)

Wearing the Royal Full Regalia and the Great Crown of Victory

Photographed in the year 1864 (B.E. 2407)

His Majesty King Mongkut (Rama IV) reigned from 1851 to 1868 (B.E. 2394–2411). Throughout his 17-year reign, Siam—then known to foreigners as Thailand—entered a period of profound transformation in its foreign trade policies. The most significant milestone was the signing of the Bowring Treaty, followed by a series of treaties with other Western nations. These agreements brought an end to the long-standing royal trade monopoly previously administered by the Royal Warehouse (Phra Khlang Sinkha), abolished numerous prohibited goods, and reformed the taxation system for foreign merchant vessels.

This marked a fundamental shift in the kingdom’s commercial traditions, laying the groundwork for a new era of free trade and diplomatic engagement with the West, and ushering in lasting economic and administrative reforms that would shape Siam’s modernization in the decades to come.

The Bowring Treaty

In the year 1855 (B.E. 2398), Sir John Bowring, plenipotentiary envoy of the British Crown, traveled to Siam to negotiate a Treaty of Friendship and Commerce, known historically as the Bowring Treaty. The negotiations were conducted in accordance with the royal policy of His Majesty King Mongkut (Rama IV). In this, Siam adopted a pragmatic and strategic approach: provisions that were clearly non-negotiable from the British perspective were granted without resistance, in exchange for concessions more favorable to Siam. The objective was to ensure that the treaty could proceed smoothly and peacefully, and to avoid the threat of coercion by Western powers, such as had been inflicted upon China and Burma in the wake of military defeat.

Sir John Bowring himself recorded: “I rose to express my deep sense of His Majesty’s gracious kindness, for the generous welcome I had received and the complete facilitation of my diplomatic mission. I conveyed my confidence that this treaty would make the name of Siam more widely known among Western nations, and would bring lasting prosperity not only to the contracting parties, but ultimately to the greater world at large…” Subsequent to the Bowring Treaty, Siam entered into similarly unequal treaties with other Western powers, including the United States, France, Denmark, Portugal, the Netherlands, and Prussia. However, Siam’s acceptance of these treaties was not from weakness, but a deliberate strategy to prevent Britain from gaining exclusive dominance. By inviting multiple powers to stake interests in Siam, the kingdom effectively created a balance of power, ensuring that no single nation could assert overwhelming control. Yet, the ultimate success of this diplomatic balancing act rested upon the statesmanship and administrative wisdom of Siam’s leadership. The survival and sovereignty of the nation in this era of colonial encroachment would depend not solely on policy, but on the enduring capability of its rulers to navigate the complexities of international diplomacy.

Sir John Bowring

(17 October 1792 – 23 November 1872)

The Bowring Treaty was a treaty concluded between the Kingdom of Siam and the United Kingdom, signed on 18 April 1855 (B.E. 2398).

Key Provisions of the Bowring Treaty Related to Trade

Export Freedom – Buyers were permitted to freely purchase and export all types of goods without restriction. However, the Siamese government retained the right to prohibit the export of certain commodities in times of famine or national emergency.

Import Regulations – Sellers were allowed to import and sell goods of any kind within Bangkok, with two exceptions: military weapons and munitions were to be sold exclusively to the government, and opium was to be sold solely to the official opium tax monopoly.

Free Commercial Exchange – Sellers and buyers were granted the freedom to engage in direct trade without interference or restriction.

Customs Reform – The traditional anchorage duties (paak ruea) were abolished and replaced with a standard import duty of 3% on all incoming goods.

The signing of the Bowring Treaty marked a pivotal transformation in Siam’s commercial system, laying the foundation for the kingdom’s modern economic development in the decades that followed.

The conduct of trade under a free trade system

Following the signing of the Bowring Treaty, a large number of foreign merchants entered Siam, and Thai goods—particularly rice—began to enjoy heightened demand in international markets. King Mongkut (Rama IV) actively encouraged rice cultivation and urged his subjects to farm to their fullest capacity. His Majesty issued a royal directive stating:

“If any subject is without a rice field to farm, the governors, officials, and local administrators shall make arrangements to allocate land to them.”

To increase productivity, efforts were made to expand arable land, and the King inspired his people by introducing more equitable tax measures, such as reforms to the land and rice taxes. These new rates were publicly printed and disseminated, ensuring that common people were informed and motivated to engage in agricultural work. In addition, the King promoted diversification in agriculture, encouraging the cultivation of sugarcane, tobacco, cotton, jute, vegetables, and fruit, thereby broadening the scope of Siam’s export economy and laying the foundations of a modern economic system.

(National Archives of Thailand, Royal Documents of King Rama IV, No. 148, Chula Sakarat 1224)

The importance of this economic transformation is reflected in the words of Professor Ingram, author of Economic Change in Thailand, 1850–1950, who wrote that:

“The most significant component of Thailand’s economic development during this period was the dramatic increase in rice production. Following the Bowring Treaty, rice exports—which had once been less than 1 million ‘hap’ (Thai volumetric measure) annually—rose to 26 million hap by the year 1951. This 100-year increase represented a 25-fold expansion in rice exports, while the population had only doubled. It may thus be said that no single economic activity has had a greater impact on Siam’s transformation since 1855 than the export of rice, the fruit of the Thai farmer’s labor.”

James C. Ingram, a distinguished economist, authored a seminal dissertation entitled Economic Change in Thailand, 1850–1970, which explores the transformation of Thailand’s economy over the course of more than a century.

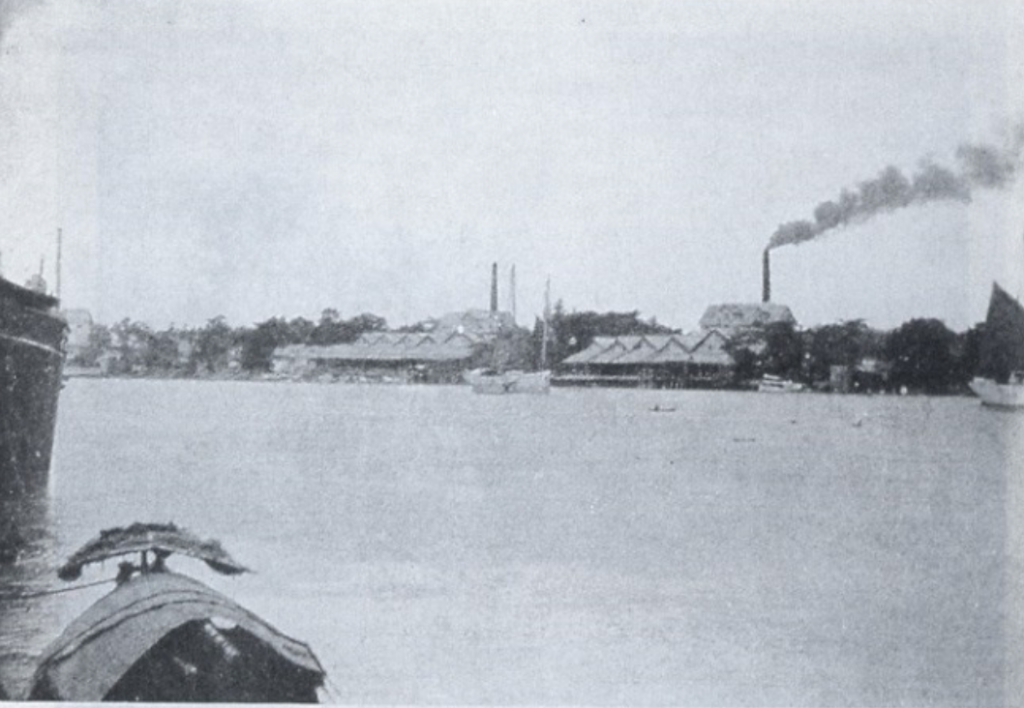

Dr. Dan Beach Bradley once remarked (Bangkok Recorder, 1866: p. 223) that Bangkok may be likened to a vast granary for the distribution of rice throughout Asia. A great number of merchant vessels awaited their cargo of rice. On 1 January 1866, no fewer than 26 foreign ships and 46 Siamese junks were anchored in the port of Bangkok, making a total of 72 vessels present at that time.

แม่น้ำเจ้าพระยา มีระดับน้ำลึกพอสำหรับเรือกลไฟ ขนาดระวางบรรทุก 1,500 ตัน และเห็นโรงสีเรียงรายทั้งสองฝั่งแม่น้ำ

“บางกอกรีเคอเดอร์, 2409:202 ระยะเวลาผ่านมาอีก 15 วัน มีเรือสินค้าเพิ่มขึ้นมาอีกเป็น 84 ลำ เรือเหล่านี้คอยบรรทุกข้าวแทบทุกลำ”

“บางกอกรีเคอเดอร์, 2409:203 แสดงให้เห็นว่าการค้าขายกับต่างประเทศขยายตัวไปอย่างกว้างขวางมาก และรัฐบาลได้เปิดเสรีทางการค้าระหว่างพ่อค้ากับประชาชน ยกเลิกผูกขาดตามสนธิสัญญาบาวริ่ง”

“กองจดหมายเหตุแห่งชาติ, เอกสารรัชกาลที่ 4 เลขที่ 122 จ.ศ. 1218 : รัฐบาลได้ออกประกาศอนุญาตให้ราษฎรซื้อขายสินค้ากับต่างประเทศ ใจความว่า บรรดาราษฎรผู้ใดมีข้าว ปลา น้ำอ้อย น้ำตาล และสินค้าอื่น ๆ เมื่อพอใจจะขายกับคนนอกประเทศก็ให้ขายตามใจชอบโดยสะดวกสบายเถิด”

The state's fiscal policy

After the abolition of the Royal Warehouse monopoly (Phra Khlang Sinkha), the state’s revenue became limited primarily to domestic taxation and customs duties on imports and exports. The loss of income formerly derived from monopoly rights and overlapping taxes on foreigners significantly reduced government revenue. In response, His Majesty introduced reforms to the fiscal system, expanding the structure and scope of taxation. A greater variety of duties were implemented through the tax farming system, whereby revenue collection was outsourced to private contractors known as tax farmers (jao phaasi nai akon). An additional 16 types of taxes and duties were introduced.

At the same time, efforts were made to increase the volume of trade, both imports and exports, by encouraging foreign merchants to conduct business in Siam. Simultaneously, the government sought to stimulate domestic production, aiming to boost economic activity from within as a means of compensating for the reduced royal income under the new free trade environment.

Industrialization and Mechanized Production

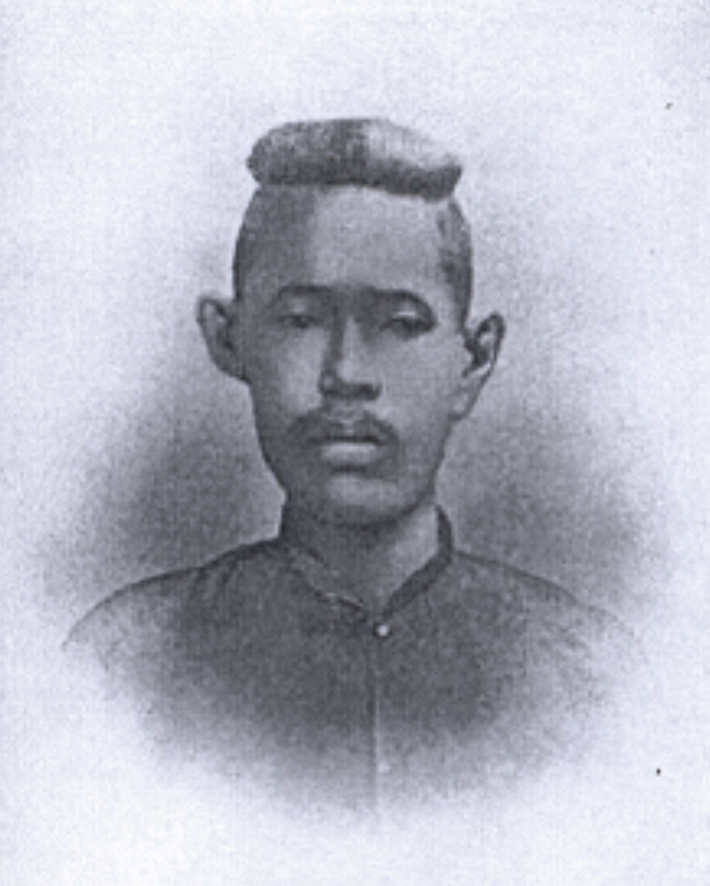

His Royal Highness Prince Isarapong

Founder of the Isarasak family (Isarasak na Ayutthaya)

(23 November 1820 – 29 October 1861)

He was a royal son of His Royal Highness Prince Maha Sakkdipolsep, the Deputy King (Uparat), and Her Royal Highness Princess Darawadi.

In 1858 (B.E. 2401), His Majesty King Mongkut (Rama IV) dispatched Prince Isarapong to observe the establishment of a cement works in Saraburi, marking one of Siam’s early steps toward domestic industrial development. In the same period, rice milling technology was introduced for the first time, with machinery used to replace manual methods in rice processing.

(Bangkok Recorder, 1866: p. 243)

A cotton ginning factory equipped with mechanical devices was also established, encouraging farmers to increase their cotton production. Cotton was now purchased directly from producers through designated factories.

(National Archives of Thailand, Royal Documents of King Rama IV, No. 161, Chula Sakarat 1277)

In addition, mechanized sawmills were introduced, replacing traditional hand-sawing methods. This innovation significantly enhanced the export capacity of Siam’s timber industry—especially in the case of teakwood, which became an increasingly valuable commodity in international markets.

(Bangkok Calendar, 1862: p. 4)

The Establishment of Foreign Trading Companies and Commercial Houses

Markwald & Co., a German commercial company

The Oriental Hotel, Bangkok, photographed circa the reign of King Chulalongkorn (Rama V), prior to 1910 (B.E. 2453). The hotel had advertised in the Bangkok Recorder as early as 1865 (B.E. 2408), making it the oldest surviving hotel in Thailand.

Image courtesy of the National Archives of Thailand.

During the reign of King Mongkut (Rama IV), a number of foreign trading companies established commercial houses throughout Bangkok, marking the beginning of modern international commerce in Siam. Among the prominent firms were Parker Goodale, Mason, Borneo, Schmit, Pickenpack, and Markwald—the latter locally known as Hang Ma-Kua—as well as Odman.

(Bangkok Calendar, 1868: p. 63)

In addition to trading companies and factories, foreign-owned hotels also began to appear in this period. Notably, Falck’s Hotel, owned by Mr. C. Falck, opened in October 1863 (B.E. 2406). Another early establishment was Carter’s Hotel, owned by Mr. P. Carter.

(Bangkok Calendar, 1869: p. 64)

Among these early institutions, the most enduring was the Oriental Hotel, Bangkok, which—according to Anek Nawigamune (2006: p. 24)—would go on to become the longest-standing hotel in Thailand, with origins tracing back to an advertisement in the Bangkok Recorder in 1865 (B.E. 2408).

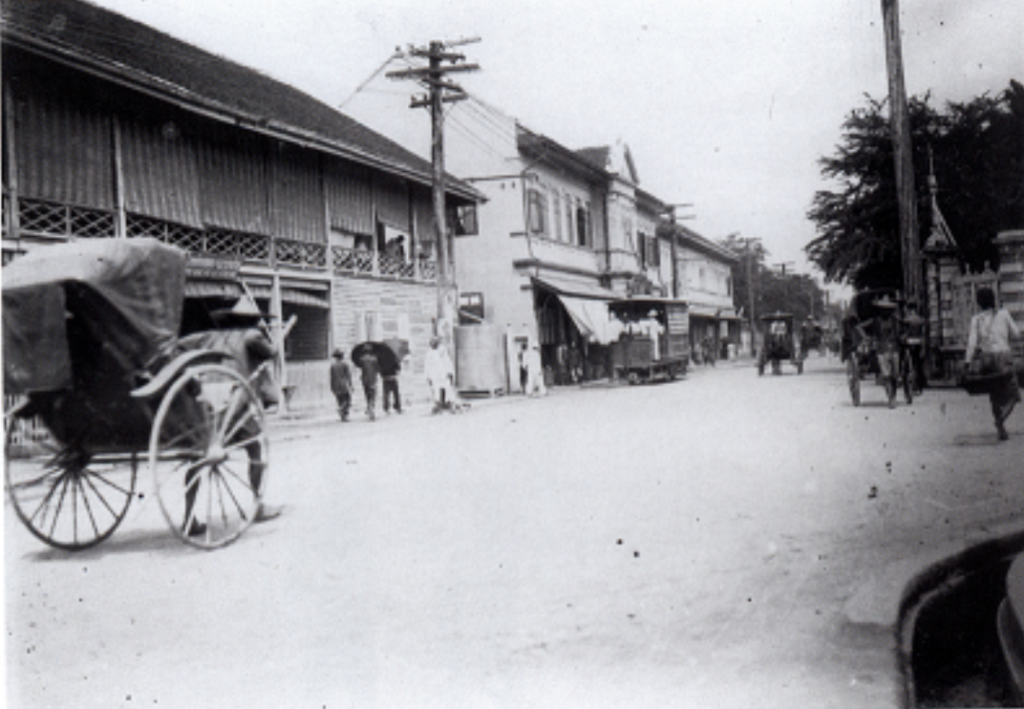

Charoen Krung Road was constructed in two phases. The southern section was commissioned in 1861 (B.E. 2404), followed by the inner section in 1862 (B.E. 2405). The two sections converged at the Upper Iron Bridge (Saphan Damrong Sthit), which became a key junction point. In its day, the thoroughfare was popularly referred to as the “New Road” (Thanon Mai), marking it as a symbol of modernization and Western-style urban planning in Bangkok.

Bamrung Mueang Road was constructed with a width of 6 meters and stretched a distance of 1.2 kilometers, running from Sanam Chai Road to Samran Rat Gate.

Transportation and Infrastructure

The row buildings (shophouses) along Charoen Krung Road appear here as a long stretch of white structures with evenly spaced windows, visible at the center of the image. This section of Charoen Krung Road was newly constructed—partly by expanding existing paths and partly by cutting new ones—in the year 1862 (B.E. 2405).

During the reign of King Mongkut (Rama IV), significant efforts were made to improve and expand both land and water transport routes in order to facilitate more efficient trade and communication throughout the kingdom.

Road construction marked a pivotal change from the traditional use of ox-cart paths to modernized roadways. In particular, major roads in Bangkok—such as Charoen Krung Road, Bamrung Mueang Road, Fueang Nakhon Road, and Si Lom Road—were developed. These roads gave rise to the construction of one-story shop houses and commercial buildings along both sides, creating new marketplaces frequented by Chinese and Western merchants.

(H.R.H. Prince Damrong Rajanubhab, 1973: p. 237)

With this transformation, land-based commerce flourished, leading to the establishment of trading houses and urban commercial districts. The Thai population gradually shifted from building homes along canals to settling along these new roads, forming a new urban society that would define Bangkok’s future cityscape.

Beyond the capital, roads were also constructed in major provincial centers. A notable example is the road from Songkhla to the border of Kedah, then under British control. Dr. Dan Beach Bradley proposed constructing a road to link Bangkok and Chiang Mai, which at the time remained under a semi-autonomous ruling prince (Chao Fa system). The road would serve to facilitate travel, commerce, and royal diplomacy between the two regions.

(Bangkok Recorder, 1866: p. 254)

In terms of waterborne transportation, the reign of King Mongkut (Rama IV) saw both the dredging of existing canals and the construction of new waterways to enhance navigation and commerce. Notable among these were Khlong Maha Sawat, Khlong Thanon Trong, Khlong Chedi Bucha, Khlong Phasi Charoen, Khlong Damnoen Saduak, Khlong Bang Li, and Khlong Lat Yi San. These canals greatly facilitated trade and travel between agricultural zones and urban markets.

Additionally, numerous bridges were constructed to connect roads across canals. These structures were built using wood, iron, and brick masonry, reflecting Western architectural influence.

(H.R.H. Prince Damrong Rajanubhab, 1961: p. 238)

This era also marked the first use of steamships for international trade, representing a major leap forward in Siam’s commercial transportation capabilities.

(Bangkok Recorder, 1866: p. 238)

Such developments signified remarkable advancements in transportation infrastructure, positioning Siam to better integrate with global trade networks during a time of accelerating modernization.

Canals, Roads, and Bridges in the Reign of King Mongkut (Rama IV) Following the Bowring Treaty

A currency-based economic system

In earlier times, Siam utilized cowrie shells (bia) and “phot duang” (bullet-shaped silver ingots known as baht) as its principal forms of currency. However, with the opening of the kingdom to free trade, an influx of foreign coins and gold bullion began to enter the country annually. This caused growing difficulties in commercial transactions, as the population was unfamiliar with foreign monetary systems and often refused to accept foreign currency.

In response, King Mongkut (Rama IV) initiated a series of monetary reforms aimed at modernizing the national currency system. In 1857 (B.E. 2400), His Majesty issued a royal letter to the Siamese diplomatic mission in England, instructing them to procure a coin-minting machine for domestic use. The delegation succeeded in acquiring such machinery from Taylor & Co. of Birmingham, which arrived in Siam in late 1858 (B.E. 2401).

By 1860 (B.E. 2403), the kingdom began minting modern coins in various denominations, including copper, tin, and gold coins, for circulation. In 1863 (B.E. 2406), the government also introduced paper money, initially referred to as mai (หมาย), and official cheques known as bai phra ratchathan ngoentara (“Royal Currency Warrants”).

To further integrate Siam into the global economy, King Mongkut implemented a standardized national monetary policy consisting of the following key reforms:

Establishing fixed exchange rates between Siamese currency and foreign currencies

Standardizing Siamese coinage to align with Western monetary systems

Issuing public proclamations to educate the population and encourage adaptation to the new monetary order

These measures marked the kingdom’s transition from a traditional barter and ingot economy to a structured monetary economy, making trade more efficient and internationally compatible.

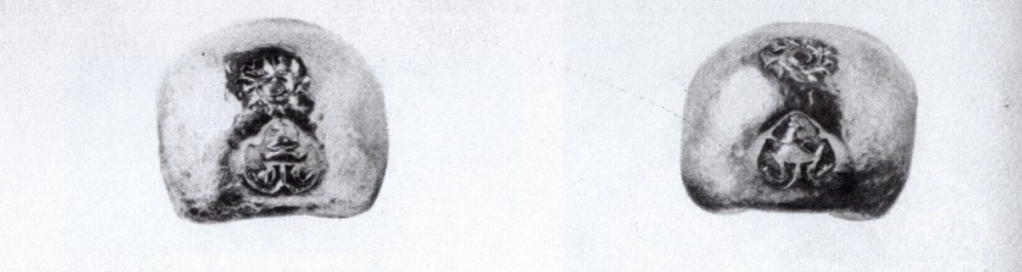

In the reign of King Mongkut (Rama IV), the traditional phot duang (bullet coin) bore the national emblem in the form of a chakra (wheel) and the royal emblem of the reign depicted as the Great Crown of Victory (Phra Maha Mongkut).

Gold coins were issued in denominations of Thot (8 baht), Phis (4 baht), and Phatdueng (10 salueng). They were first minted and circulated in 1863 (B.E. 2406) and remained in use until their withdrawal in 1908 (B.E. 2451).

Concepts and Methods for Restructuring the Economic System to Lay the Foundations for National Development

In retrospect, while the Bowring Treaty may be viewed as a significant step that propelled Siam into a modern economic system and helped transform the kingdom into a capable nation-state, fully prepared to engage diplomatically with Western imperial powers, it must also be acknowledged that the treaty contained numerous provisions disadvantageous to Siam. Chief among these was the loss of judicial extraterritoriality, which severely weakened the kingdom’s ability to assert sovereignty over foreign nationals within its own borders. To many Thais and foreigners alike, it created the impression that Siam had relinquished a portion of its independence, drawing unfavorable comparisons to neighboring territories that had fallen under direct colonial rule, particularly British.

King Mongkut (Rama IV) was well aware of these concerns and addressed them explicitly in a royal proclamation.

(National Archives of Thailand, Royal Documents of King Rama IV, No. 550, M.M.P.: 1)

He wrote:

“I have heard that many princes and officials have been murmuring that the present difficulties arise because the members of the royal court and the inner palace have grown too close to the British—learning their language, using their writing, and engaging in trade with them. Thus, the British have become overly intrusive and caused us much annoyance. Some even claim that this is how we lost Koh Mak Island, once Thai, now in British hands. Was it not because someone formed ties with the British? Singapore, too—once the territory of Johor Malays—is now a major British trading port. Back in the year 1181 of the Chula Sakarat calendar, we called it ‘the new city,’ and still do to this day. Who was it among the Thai nobility that forged relations with the British then?”

This evidence illustrates the delicate balance Siam had to maintain—opening the kingdom to international trade in the interest of survival, even at the cost of temporary disadvantage. While certain provisions placed Siam at a legal and diplomatic disadvantage, the treaty also served to lay the foundation for modernization, particularly in language education, systematized commerce, and broader exposure to global institutions. These would, in time, provide more benefit to the kingdom as a whole than to any particular class of individuals.

As a sovereign and perceptive ruler, King Mongkut understood both the conditions faced by neighboring states and the real threats posed by the superior military power of Western empires. He knew well that Siam could not prevail through armed resistance and thus chose instead a policy of strategic accommodation, accompanied by domestic reform. He prioritized the development of the nation’s economy, society, and institutions to reduce potential harm and simultaneously seized this as an opportunity to modernize Siam on its own terms.

He remarked in a royal statement (same source, p. 3):

“As things stand now, our country is surrounded on two or three sides by powerful nations. What then will become of a small country like ours? Suppose, for instance, that we were to discover a gold mine within our territory and could extract gold in great quantities—enough to sell and buy one hundred warships. Even then, how could we possibly contend with those powers? The reason is simple: we would still have to purchase those ships and weapons from the very countries we would be preparing to resist. We do not yet possess the capability to manufacture such instruments of war ourselves. And even if we did have the money, they would stop selling to us the moment they saw us growing too strong for our own good. In the future, our most important weapons will be none other than our words and our minds—fully equipped with reason and cleverness. These alone may suffice to serve as our defense.”