The King Mongkut Studies Initiative

His Vision for Civil Rights and Liberties

King Mongkut of Siam was profoundly aware of the looming threat posed by the great Western powers. During his monastic years, His Majesty devoted himself to studying foreign knowledge through newspapers and Western treatises, which he had either purchased himself or had been presented by foreign acquaintances. He frequently engaged in intellectual exchange with foreigners, thus acquiring a discerning understanding of global affairs and the predicament his kingdom might face—even before he ascended the throne.

Upon his accession to the throne, His Majesty initiated a series of reformist policies aimed at advancing the Siamese state along the path of Western modernization. Though he reigned as an absolute monarch under the traditional system of divine kingship (Chakravartin), he refrained from exercising his supreme authority in a manner that might burden or oppress his subjects. Instead, he consistently emphasized that his kingship was derived from the will of the people. This sentiment is inscribed in the Phra Suphanabat, the royal charter, wherein he is acknowledged as Mahachon Nikorn Samo Sorn Sommot, meaning “elected by the assembly of the people” (as cited in Chulachakrabongse, Lord of Life, p. 359).

In royal correspondence with Lieutenant-Colonel Butterworth, the British Governor of Prince of Wales Island (Penang), dated 21 April, His Majesty styled himself “Newly Elected President or Acting King of Siam,” and in another letter dated 22 May, referred to himself as the “Newly Enthroned King of Siam” (as noted in Malcolm Smith’s A Doctor in the Royal Court of Siam, p. 65). Even when issuing public proclamations to dispel false rumors, His Majesty affirmed that his royal power was contingent upon the consent and collective will of the people. This reveals that His Majesty held the happiness and welfare of his subjects in the highest regard.

Consequently, His Majesty espoused a philosophy of constitutional monarchy and democratic principles well ahead of his time. He was the first monarch to partake in the Nam Phra Phithap Sattha oath alongside his people—an act symbolizing his solemn pledge of loyalty and integrity to the nation. He also welcomed the counsel of others, entrusting members of the royal family, nobility, and senior officials with the responsibility of selecting judicial officers. These appointments were made through a majority vote, regardless of whether the individuals were personally favored by the King. In so doing, His Majesty laid the groundwork for civil liberties and greater participatory governance among the citizenry of Siam.

The Petitioning of Grievances and the Election of Judicial Officers

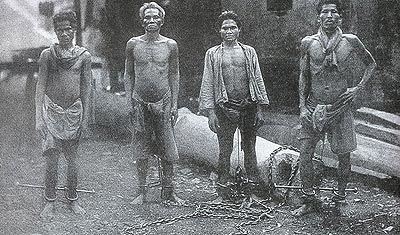

A Heavily Convicted Prisoner in Shackles

(Image from: Samutphap Muang Thai, Vol. 2, n.d., p. 31)

His Majesty reformed the custom of submitting petitions, allowing the people to present grievances directly to the King without punishment or needing to pass through officials. He received petitions every Wednesday. If the petitioner was imprisoned, relatives or guarantors could submit on their behalf. Petitions could be self-written or by others, provided they were concise and clear.

Subjects were granted the right to file grievances even against royal officials or nobles close to the King. For example, a petition from Rayong accused the local governor. His Majesty appointed a judicial committee to ensure just and impartial trials. Each petitioner received one salueng as a preliminary reward, and another salueng if the case was judged in their favor. Those who petitioned in person were granted two salueng for paper, pencils, and writing fees (Royal Decrees Nos. 81, 128).

In cases where judges were accused of bias, His Majesty issued a decree (No. 298) permitting plaintiffs to select judges whom they trusted. If injustice was perceived, subjects could appeal directly to the King.

Religious Observance

During His Majesty’s reign, numerous Christian missionary groups from the West entered the kingdom to propagate their faith. Aware that religious propagation was among the strategies employed by colonial powers, the King responded with a policy of religious tolerance. He granted his subjects the liberty to choose their faith freely and to practice its rites without restriction.

Rather than enforcing conformity, His Majesty encouraged the people to deliberate thoughtfully and to adopt a religion that truly offered intellectual and spiritual refuge—one that aligned with reason, rather than mere custom or social influence. In a royal proclamation (No. 165), he declared:

“The pursuit and observance of a religion which serves as a refuge in this life is indeed a most commendable endeavor. Therefore, all persons should consider and reflect with their own intellect. When the merit of a given religion becomes evident, and it proves itself a refuge suitable to reason, then let them adhere to and practice that religion of their own volition.”

As for the monastic order, although the King founded the Dhammayutika Nikaya to reform and purify Buddhist practice, he never imposed exclusivity. Buddhist monks were granted freedom to choose between the Dhammayutika and Mahanikaya sects, according to their personal convictions and spiritual discipline.

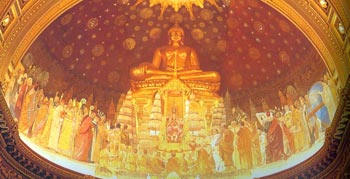

Image of King Rama IV fostering religion, depicted on the western dome of the Ananta Samakhom Throne Hall

(Source: Dusit Palace: The Royal Residence Compound, 2002, p. 212)

Elevation of the Status of Women

Mrs. D. B. Bradley

(from the book Somdet Phra Chom Klao, King of Siam, Volume I, 1973, p. 124)

Mrs. Stephen Mattoon (or Mattoone)

(from the book Somdet Phra Chom Klao, King of Siam, Volume I, 1973, p. 124)

King Mongkut (Rama IV) graciously abolished many cruel and oppressive customs, especially those pertaining to the abduction or forced marriage of women. He affirmed the right of women to choose their own spouses, raising the status of women to equality with men—an extraordinary advancement in a society where women had long been subjected to subjugation, likened to animals or beings of lesser worth, while men were regarded as fully human.

The King issued royal decrees forbidding husbands from selling their wives, prohibiting parents from selling their children, and outlawing forced marriages in which daughters were compelled to wed without their consent (Royal Decrees No. 271 and 294). In the same spirit, His Majesty allowed royal consorts, concubines, and ladies of the inner court the freedom to respectfully resign their courtly status and remarry at will.

Furthermore, the King elevated the status of women by granting them equal rights to education. He commissioned Mrs. Bradley and Mrs. Mattoon, wives of foreign missionaries, to teach English, literature, and science to royal consorts and ladies of the court. This initiative reflected His Majesty’s foresight in preparing the women of the palace for effective communication and intellectual engagement with Westerners, who were increasingly influential during his reign.

(Source: Wilailak Thawornthanasarn, “Thai Elites and the Adoption of Monetary Culture”, pp. 81–82)

Expanding Educational Opportunities to the Common People

Women at the Missionary School during the Reign of King Mongkut (Rama IV), in a Classroom Where Mrs. House Taught Literacy, Sewing, and Laundry Skills

(Image from: Chum Num Phap Prawattisat Phaendin Phra Bat Somdet Phra Chom Klao Chao Yu Hua, 2006, p. 156)

His Majesty recognized the importance of education and actively promoted the establishment of modern schooling, thus becoming a pioneer in expanding learning opportunities to commoners and women. After founding the Rajakumari and Rajakuman schools within the Grand Palace for royal children, His Majesty granted permission to Christian missionaries to establish schools both in Bangkok and the provinces (Lao Rueang Phra Chom Klao, 2004, p. 12). As a result, many nobles and officials enrolled their sons and daughters for formal education in these institutions.

Upon establishing a royal printing press, official documents and government notices were published and distributed widely to governmental departments and local communities, making knowledge accessible to the broader population. Eventually, various textbooks were printed for public circulation, including Chindamani, Prathom Kor-Kor, Prathommala, as well as texts on craftsmanship and medicine. These efforts significantly broadened the reach of education to the common people, granting them greater access to information and the tools for intellectual advancement.

A private school for female students was established by a missionary group in Phetchaburi Province in the year 1865 (B.E. 2408).

Now known as Arunpradit School

(Image from the book “Somdet Phra Chom Klao of the Kingdom of Siam,” Volume I, 1973, p. 156)

His Majesty deeply recognized the importance of education and earnestly promoted the development of modern schooling, becoming a trailblazer in expanding learning opportunities to both commoners and women. Upon founding the Rajakuman and Rajakumari schools within the Grand Palace for royal children, His Majesty graciously permitted missionaries to establish schools throughout the capital and provincial cities (Lao Rueang Phra Chom Klao, 2004, p. 12). These schools drew widespread enrollment from the children of nobles and officials alike.

Following the establishment of the royal printing press, government documents and official notices were widely printed and distributed to government offices and communities, providing the populace with access to knowledge. Later, books were printed for public sale, including Chindamani, Prathom Kor-Kor, Prathommala, as well as manuals on craftsmanship and medicine. This marked a significant expansion of educational opportunities for the common people, enabling them to better access knowledge and current information.

Theatrical Performances

During the reigns preceding that of King Mongkut, royal edicts strictly forbade members of the royal family, nobility, and officials from training or participating in female theatrical troupes. Consequently, royal court dramas performed exclusively by women were confined to the Grand Palace alone. However, under the enlightened rule of His Majesty King Mongkut (Rama IV), this custom was revised. His Majesty graciously permitted all-female theatre troupes to perform publicly beyond the palace grounds. He remarked that the presence of multiple theatrical groups would enliven the realm and bring honour to the kingdom (Royal Proclamation No. 70).

Furthermore, the King allowed public performances of his own royal dramatic compositions—an unprecedented liberty. Traditionally, public theatre, or lakhon nok, was limited to Jataka tales or local folk narratives. Under the new regulation, such restrictions were relaxed. Nevertheless, His Majesty strictly forbade the coercion of boys or girls into theatrical training against their will, thereby upholding individual freedom and dignity even in the realm of entertainment.

The Siamese Theatre of Phraya Burut Rattanaraj Phallop

(Pheng Phenkul – Adopted Royal Son of King Rama IV, Later Elevated to Chao Phraya Mahintharasakdithamrong)

Subsequently Renamed as Prince Theatre

Photograph circa 1867

Featuring Performances by Real Men and Women

Land Ownership during the Reign of King Mongkut (Rama IV)

His Majesty promulgated the Royal Land Pricing Act to ensure that commoners who possessed homes, fields, or orchards would receive fair compensation for their land rights. Though vested with absolute power, the King had no intent to exploit his subjects. He decreed that henceforth, if the sovereign required any land—whether houses, fields, or gardens—for royal palaces, residences, or estates to be granted to members of the royal family, court officials, or devout servants, the Crown would provide payment into the state treasury. Those funds would then be used to purchase alternate land, fields, or homes for distribution to those entitled.

Furthermore, peasants holding land under the official “red deed” title were permitted to sell or pledge their land. Should they wish to redeem it later, the King decreed they could buy it back at a price satisfying the new owner. At the same time, landowners whose properties lay within designated zones were allowed to sell outright to foreigners—often fetching higher prices due to foreigner generosity—with the transaction keeping wealth within the realm. (Royal Proclamation No. 86)

The Rice Trade and Employment with Foreigners

Warehouse along Khlong Bang Luang (Khlong Bangkok Yai), Thonburi Side

(Image from: Chum Num Phap Prawattisat Phaendin Phra Bat Somdet Phra Chom Klao Chao Yu Hua, 2006, p. 188)

In earlier reigns, maritime trade with foreign nations was the exclusive privilege of the Royal Warehouse, members of the royal family, princes, and high-ranking officials. However, following the signing of the Bowring Treaty, the structure of the economy shifted from a monopolistic system to one of free trade (Pensri Duke, Foreign Affairs, Sovereignty and Thai Independence, 2001, p. 7). For the first time, the exportation of rice was officially permitted, enabling commoners to engage freely in the rice trade and to seek employment with foreigners. This led to increased income for the populace and a widespread expansion of commercial activity (Royal Proclamations No. 92, 95, 120).

At times, the volume of rice exports grew so large that it caused domestic prices to surge. There were instances when demand from foreign buyers prompted local sellers to inflate prices. In response, the monarch issued a declaration stating that if those in possession of rice wished to profit and those in fear of scarcity desired to purchase for security, the royal government would not object — trade was to be conducted freely according to the will of the people.

Nevertheless, in years when floods devastated the paddies, domestic rice production fell short of national consumption needs. To address such shortages, the King issued proclamations discouraging hoarding or price manipulation by merchants. Furthermore, proclamations were issued advising the public to reserve enough rice for domestic sustenance, including orders prohibiting the export of rice abroad during critical times (Royal Proclamations No. 95, 243).

Freedom of Expression and Access to Information

When Dr. Dan Beach Bradley introduced the Thai-script printing press to the Kingdom and published the Bangkok Recorder, it marked a momentous shift in the dissemination of knowledge and public discourse. Beyond religious and scientific enlightenment, the Bangkok Recorder provided the common people with a rare opportunity to express opinions and engage in the critique of public affairs—even extending, at times, to the monarchy itself.

Such openness did not go unnoticed. His Majesty King Mongkut issued royal proclamations (No. 333, 335) cautioning the populace against blindly believing everything published in the Bangkok Recorder. Yet significantly, he did not suppress the publication; rather, he affirmed the people’s right to inquire and seek truth by allowing them to submit questions directly to the throne regarding circulating rumors. This gesture powerfully underscored that the right to expression and critical thought were not only permitted, but protected.

In a further effort to ensure transparency and justice, King Mongkut commanded that all tariff rates and tax codes be calculated and printed for public distribution throughout all districts (Proclamations No. 56, 180), thereby safeguarding the populace from exploitation by local officials (Proclamation No. 94). Should grievances arise, the people were granted the legal right to bring suit (Proclamation No. 143).

Moreover, the establishment of the Royal Gazette (Ratchakitchanubeksa) as a regularly issued publication reflected a deeper commitment to institutional transparency. Through these bulletins, proclamations were not only declared but widely disseminated to be read and understood by the citizenry (Proclamation No. 116), confirming that access to information was regarded as a civic right.

Altogether, these reforms illustrate that under King Mongkut’s enlightened rule, freedom of expression and access to information were nurtured as vital components of a just and modern state.

Royal Audience

Royal Progress and Public Audience During Provincial Tours

In the course of His Majesty King Mongkut’s royal excursions to provincial cities, His Majesty graciously permitted the common folk to present themselves before His royal personage, allowing them the privilege of beholding the splendor of royal majesty. On such occasions, His Majesty welcomed all manner of petitions and supplications from the people, who were thus afforded a rare and reverent opportunity to bring forth their concerns directly to the sovereign.

Furthermore, His Majesty commanded that foreign subjects residing within the realm, who came to pay their respects, be permitted to do so according to the customs of their own lands, in accordance with a royal edict which reads: “Let not the provincial officers, district chiefs, nor the city guards gather in tight circles to block the people from approaching the royal route. Let no officials of the royal procession or local governors drive away villagers who have come to witness the passing of their Sovereign.

Forbid them from scolding or discouraging foreigners who, by their own tradition, wish to show respect in the manner of their homeland.”

(Royal Edict No. 108)

Such proclamations exemplify the far-sightedness and enlightened vision of His Majesty King Mongkut. It was by virtue of this magnanimous and open-hearted governance, coupled with astute understanding of international affairs, that the Kingdom of Siam was able to maintain her independence and sovereignty, even as the imperial powers of the West vied relentlessly to expand their colonial dominions.

Bibliography

Proclamation on the Form of Language to Be Used in Petitions to His Majesty

Proclamation Granting Permission for Inner Court Officials to Resign from Royal Service

Proclamation on the Publication of Tariff Duties for Public Notification

Proclamation Concerning Female Theatre Performances, Physicians, and Artisans

Proclamation Regarding the Right to Submit Petitions to the King

Proclamation Regarding Zones Where Foreigners May Rent or Purchase Land

Proclamation Advising Citizens to Purchase Rice Before Export is Permitted

Proclamation Permitting Bangkok Dwellers to Work for Foreigners

Proclamation Prohibiting Panic Regarding the Movement of Warships

Proclamation Admonishing Both Buyers and Sellers of Rice

Proclamation Establishing Set Times for Submitting Petitions to His Majesty

Proclamation Admonishing the Sale and Purchase of Rice in the Year of the Snake

Proclamation Permitting Siamese Subjects to Work for the British Consulate

Proclamation Abolishing the Firing of Salutes and Permitting the Public to Pay Homage Along the Royal Route

Proclamation on the Manner of Presenting Petitions to His Majesty

Proclamation on the Selection of Royal Teachers, Jurors, Royal Brahmin Priests, and Royal Astrologers; on Payment of Taxes to Support the Capital

Proclamation Requiring Petitioners to Sign Their Names or Delegate a Trusted Person to Sign on Their Behalf

Proclamation Granting Royal Permission for Consorts to Resign; on Royal Consorts, Mothers of Princes and Princesses, and Noble Ladies with Husbands

Proclamation on Religious Observance and Those Who Choose the Wrong Faith

Proclamation Allowing Ladies of the Inner Court to Resign from Royal Service

Proclamation to Summarize Civil Complaints Filed by the People for Royal Consideration

Proclamation Urging the Preservation of Rice for Domestic Consumption Throughout the Year

Proclamation Abolishing the Coconut Product Tax

Proclamation Regarding the Price of Rice

Proclamation Containing Royal Counsel to Rice Buyers and Sellers

Proclamation Prohibiting the Export of Rice Abroad

Proclamation Banning the Official Setting of Rice Prices

Royal Act on Abduction

Proclamation Forbidding Adorning Children with Gold or Silver and Leaving Them Unattended

Proclamation on Mortgaging and Selling of Land Ownership Rights

Supplementary Royal Act on the Mortgage and Sale of Land Ownership Rights

Royal Act Prohibiting Husbands from Selling Their Wives and Parents from Selling Their Children

Proclamation of the Grand Songkran Festival, Year of the Dragon, Samritthisok Era

Proclamation Directing That Judges Be Selected Who Are Acceptable to Litigants

Toyota Thailand Foundation. (2004). Collection of Royal Proclamations of King Rama IV. Bangkok: Toyota Foundation.

Prince Chula Chakrabongse. (1974). Chao Chiwit [The Sovereign Life] (4th ed.). Bangkok: Khlang Witthaya. p. 359.

Smith, Malcolm. (2003). A Farang Doctor in the Siamese Court (3rd ed.). Bangkok: Ruam Thansan.

Dhamma Sapa and Banlue Dhamma Institute. (1999). The Royal Dharma, Biography, and Deeds of His Majesty King Mongkut. Bangkok: Dhamma Sapa. p. 125.

Duke, Phensri. (2001). Foreign Affairs and the Sovereignty of Thailand. Bangkok: Royal Institute. p. 7.

Thongtor Kluaymai na Ayudhya. (2005). Stories of King Mongkut. Bangkok: Fine Arts Department.

Wilailekha Thawornthanasan. (2002). The Thai Elites and the Reception of Western Culture. Bangkok: Muang Boran Publishing. pp. 81–82.

Proclamation No. 43

Proclamation No. 52

Proclamation No. 56

Proclamation No. 70

Proclamation No. 81

Proclamation No. 86

Proclamation No. 88

Proclamation No. 90

Proclamation No. 92

Proclamation No. 95

Proclamation No. 99

Proclamation No. 104

Proclamation No. 105

Proclamation No. 108

Proclamation No. 120

Proclamation No. 128

Proclamation No. 146

Proclamation No. 153

Proclamation No. 156

Proclamation No. 165

Proclamation No. 209

Proclamation No. 219

Proclamation No. 243

Proclamation No. 245

Proclamation No. 252

Proclamation No. 253

Proclamation No. 256

Proclamation No. 266

Proclamation No. 271

Proclamation No. 282

Proclamation No. 283

Proclamation No. 290

Proclamation No. 294

Proclamation No. 296

Proclamation No. 298