King Taksin The Great

Chapter 9: King Taksin’s Royal Duties in the Economic Sphere

9.1 What were the economic problems during the Thonburi period when it served as the capital?

9.1.1 Economic Problems in the Early Thonburi Period

The economic problems during the early years of the Thonburi Kingdom primarily pertained to the livelihoods and sustenance of the populace. The second fall of Ayutthaya to the Burmese in 1767 (B.E. 2310) inflicted catastrophic devastation upon the kingdom, causing ruin and desolation in nearly every aspect of society. The national economy fell into a dire state of decline, the likes of which had never been seen before. Agriculture came to a halt, as did commerce with foreign nations. The Thai people were plunged into a great famine, having been unable to farm for two consecutive years due to the ongoing warfare and the continual incursions of the Burmese. At that time, Siam found itself in a severe state of scarcity. The people starved, becoming emaciated and feeble. Disease and death were widespread. The scene was one of great sorrow and pity. Even garments and basic clothing were in desperately short supply. The Pali-language Chronicle of Ayutthaya, composed by Phra Phimontham (later elevated to Somdet Phra Wannarat during the reign of King Rama I), offers a vivid depiction of this famine:

“In that grievous time, the people of Ayutthaya were consumed by sorrow, lamentation, and hardship. Hunger and starvation rendered many physically debilitated. Some were torn from their kin, spouses, children, and parents. Deprived of all necessities, they became destitute and helpless, akin to untouchables—without food, raiment, or shelter. Emaciated and disfigured, they survived by subsisting upon fruits, leaves, vines, lotus roots, and bark.”

“These wretched souls wandered the forests and countryside, struggling to preserve their lives. In their desperation, they gathered in bands, plundering and fighting amongst themselves for paddy, rice, and salt. Some possessed nothing; others, very little. Their bodies grew so lean and weak, their flesh and blood depleted, that they died from suffering—some succumbing, others barely clinging to life.”

“The Siamese even took up arms against monks, accusing them of betrayal. Pagodas were ransacked, and Buddha images destroyed in the hope of retrieving hidden treasure.”

The food shortage was so severe that many perished daily. Those who survived were left enfeebled and frail. Clothing and cloth were likewise scarce. The utter deficiency of the Four Requisites—food, clothing, shelter, and medicine—caused great disorder, and the social order broke down. Prior to the fall of Ayutthaya, many of the wealthy had buried their treasures in temples or secluded places. In their desperation, some resorted to looting monasteries, seizing arms against the clergy, and destroying Buddha images or stupas in the hope of retrieving hidden wealth to sustain themselves.

As recorded in the Royal Chronicles, Volume 39: “The Siamese, moved by some belief of theirs, had concealed gold and silver in great quantities within the bodies of Buddha images—some in the head, some in the chest, some in the feet, and much within the stupas. A single stupa yielded four jars of silver and three jars of gold. Those who destroyed such statues were rarely unrewarded.”

The digging up of these hidden treasures helped some survive, yet the persistent lack of agricultural output meant that gold and silver lost their value. Gold became so abundant that it could be gathered by the handful from the roads, which were littered with ashes and copper scraps. Temples and buildings were dug up and riddled with holes. Nonetheless, the circulation of these treasures yielded some economic benefit, as it rekindled financial activity. This circulation proved advantageous later when economic conditions began to recover and trade with foreign merchants resumed. (The Royal Biography and Royal Duties of His Majesty King Taksin the Great, cremation volume of Miss Phan Na Nakhon, 20 September 1981, p. 5)

The memoirs of the French Catholic missionaries who resided in Siam at the time recorded the famine in the Royal Chronicles, Volume 39, as follows: “The price of food in this city is exceedingly high. At present, rice sells for two and a half silver coins per thanan. Even the most diligent laborer cannot earn enough to feed himself alone—what then of his wife and children?”

Another passage recounts: “The king’s subjects suffer great hardship. Many perish each day due to the most extreme food scarcity. In this year (B.E. 2312 / A.D. 1769), more people died than during the Burmese assault on Ayutthaya.”

In the History of Thailand during the Ayutthaya Period by François Henri Turpin, it is recorded that prices of rice rose so high that it became a rare commodity in the marketplace. Taro roots, yams, and bamboo shoots became the principal foods during this famine. Most people were afflicted with strange illnesses; some lost their memory and spoke incoherently, becoming mad with startling ease. Such accounts vividly illustrate the terrifying severity of the epidemic during that time.

The desperate hunger and emaciation of the people greatly grieved His Majesty. He was deeply troubled by the dire conditions of his subjects. This sentiment is likewise recorded in the Royal Chronicle of the same period:

From that time onward, with great royal compassion and tireless exertion for all beings and the Buddhist religion, His Majesty could no longer rest, bathe, or dine in peace. Monks, nobles, ministers, citizens, paupers, and beggars from every province gathered to receive royal relief, numbering more than ten thousand in total. All military and civil officials, Thai and Chinese alike, were granted one thang of rice each, sufficient for twenty days’ sustenance.

At that time, no one could yet return to the fields. Food was so scarce that rice brought in by Chinese junks sold for three baht per thang, or even one tamlueng, and at times five baht. Still, through royal wisdom and benevolence, His Majesty strove to nourish all living beings. He gave away vast quantities of garments, fabrics, silver, and money beyond measure.

So sorrowful was His heart that He uttered:

“Should there be any being — deity or man of supernatural might — who could restore the abundance of food and bring peace to all beings, and should he ask for one of my royal arms, I would willingly sever and offer it unto him. Such is the truth of my compassion.”

Thus, in addition to the restoration of the kingdom and the relocation of the capital to Thonburi, His Majesty King Taksin bore also the grave responsibility of reviving the realm’s shattered economy from ruin.

9.1.2 Natural disasters caused problems such as irregular rainfall that failed to arrive in the proper seasons, damaging the rice fields after sowing. In addition, insects and rats constantly gnawed at the roots of rice plants and other crops, preventing sufficient harvests to sustain life. As a result, banditry became rampant everywhere, and the people had to keep weapons at hand at all times.

“The destruction of rats, which fed on the ripe rice causing grains to fall to the ground, prevented the people from finding reptiles, termitaria mushrooms, or large tubers—each enough to feed one person. Insects swarmed over the corpses, darkening the air, and humans had to endlessly contend with these pests.”

9.2 How did Somdet Phra Chao Taksin the Great resolve the livelihood woes of His subjects?

King Taksin’s Royal Duties in Resolving Economic Problems after the Second Fall of Ayutthaya had several important aspects as follows:

9.2.1 Solving the Famine and Shortage Problem of the People (Short-term)

The most urgent and critical problem to be addressed immediately was the famine and shortage of essential goods among the people. King Taksin took action by spending a large amount of royal funds to purchase rice brought in by foreign merchants on their junks, paying exceptionally high prices—3 to 5 baht per jar, sometimes up to 6 baht per jar, which was very expensive at the time. Compared to present-day values, this would be about 2,000 baht per jar. He then distributed this rice generously to tens of thousands of starving people, including both military and civilian officials, who each received one jar for every 20 days. (Sujit Wongthes, 2002: 130) At the same time, he also ordered the purchase and distribution of large quantities of clothing and garments, which immediately alleviated the suffering of the people.

Where did King Taksin get the money to buy food and supplies to distribute to the people and army?

For the funds used to purchase consumables for distribution, His Majesty sent officials to Ayutthaya to organize the excavation of treasures and to collect taxes from the recovered wealth (Pharadee Mahakhan, 1983: 29-30). He also used royal treasures seized from the Burmese to buy rice from foreign junks and allocated it to the subjects.

King Taksin brought forth his own treasures, as well as those of his mother and siblings, which they had accumulated, to aid the royal administration. He ascended an empty realm, devoid of palaces, valuables, and treasury stores. (Woramai Kobilsingh, 1997: 61) Moreover, his soldiers of Chinese descent reached out to relatives and merchants, pooling approximately ten thousand taels of silver, along with rice, salted fish, and other provisions—though these were not officially accounted for. (Woramai Kobilsingh, 1997: 65) Additional offerings came later, as well as proceeds from trading ships. (1997: 80–81)

Later, a relative named Jianjin petitioned to borrow money from Chinese officials and the King of Beijing to purchase firearms, steel for swords, and quality swords from nearby cities, as well as spears, halberds, and pikes. It is said that they borrowed about sixty thousand taels from merchants, officials, and the King of Beijing combined. (1997: 82–93)

The royal funds that were spent on rice and clothing to support the distressed officials and populace during those harsh times are believed by King Rama V (Somdet Phra Chulalok) to have come partly from the spoils of the Burmese camp at Pho Sam Ton.

Suree Phumiphomorn (1996: 78) noted that the sale of tin, ivory, and timber helped raise money to buy food and clothing.

In another passage, King Rama V wrote: “No matter from where the money came, the Lord of Thonburi purchased rice to distribute evenly to sustain life during hardship. Those who were full were full together, those who were hungry were hungry together.”

In the memoirs of Krom Luang Narindhara Thewi, it was recorded that “The unused Burmese cannons were melted down to extract metal (likely brass or bronze) to be loaded onto junks. Rice was purchased at 6 baht per jar, feeding over a thousand starving people.”

This clearly demonstrates that King Taksin tirelessly sought funds by every possible means to procure rice for distribution to the starving populace—even going so far as to melt down unusable cannon metal and sell it abroad to buy food for his starving people.

“In 1769, His Majesty showed great compassion for the people. The damage caused severe famine, one of the consequences of war. Work was temporarily halted, and the farmers could only cultivate a small amount of rice.”

“Under these dire circumstances, Phraya Taksin showed mercy and kindness, declaring that hardship would no longer mean starvation. He opened the royal granaries to provide relief…”

The famine during the early Thonburi period likely lasted several years, as evidenced in the Phan Chanumas (Cherm) edition of the Thonburi Royal Chronicles, which recorded that even in 1770 (B.E. 2313), rice was still being purchased and distributed:

“At the beginning of the year 1132, the year of the Tiger, the year of sorrow (B.E. 2313)… rice cost 3 chang per cartload. By the grace of the King, rice was imported from the south in abundance. The surplus was organized for the army, and donations were given to monks, Brahmins, beggars, wanderers, and all families of the royal subjects…”

Regarding this royal rice distribution, there is an anecdote passed down by elders. During the early reign of King Rama V, an old man from Bang Pratun on the Thonburi side recounted to his descendants that his father had personally witnessed these events. When people evacuated from Ayutthaya to settle in the new capital Thonburi, and the people faced severe famine and hardship, King Taksin was deeply concerned about their welfare.

He rode his royal elephant personally to distribute rice and clothing to the people every day. The people praised and crowded around, pressing so close to the royal elephant that the King, worried the elephant might harm someone by stepping or poking, cautioned the crowd saying, “Do not come close, my child, or the elephant might hurt you.”

The royal words filled with compassion for His subjects left a deep and lasting impression upon the people there. Beyond being a monarch who relieved suffering and brought happiness in a manner rare among kings, His Majesty also spoke words overflowing with mercy and kindness, bringing immense joy to all who heard His royal utterance, especially during times of severe hardship and famine such as these. His royal duties and compassionate speeches were like the elixir of life that revived all beings, who were near death, back to vitality and joy.

This royal conduct was another essential quality that earned Him the lasting respect and love of the populace for well over two centuries.

By addressing the immediate famine crisis through generously purchasing rice and essential goods for distribution to relieve the hunger and scarcity of the people, as previously mentioned, He brought about threefold benefits to the nation and the general populace:

When all the merchants learned that goods sold in Thonburi fetched good prices and sold well, they increasingly brought in paddy rice, milled rice, clothing, and various necessities to sell in Thonburi. This ensured that the citizens had sufficient food and clothing, ending the famine and shortages.

As merchants competed to bring in more diverse goods to sell, this caused a surplus in the market that exceeded the people’s demand. Consequently, prices gradually fell, and the hardship of the populace slowly diminished.

Many citizens who had previously scattered and hidden from warfare in various places, upon hearing that King Taksin of Thonburi compassionately cared for his people and prevented starvation, rejoiced and gradually returned to their original homes and towns. This increased the population of Thonburi significantly, providing greater strength to defend the kingdom against enemies. The people resumed their livelihoods and trades, restoring towns that had been deserted to normalcy and prosperity. Thus, the nation’s economy began to recover steadily and improve continuously.

The importance of Ayutthaya and Bangkok lies in their status as large cities situated along riverbanks where long-distance sea vessels could dock. This enabled their growth as major port cities for trade and international transportation, in addition to serving as the capitals and administrative centers of the kingdoms. Moreover, Thailand built seafaring ships to carry Thai goods overseas. One such vessel was the traditional Thai junk, which used to berth along the banks of the Chao Phraya River, from its mouth up to Bangkok. These ships gradually disappeared about 50 years ago. (Image courtesy of Muang Boran)

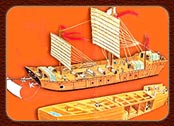

A cross-sectional illustration of a traditional Thai junk ship, adapted from Chinese junks, shows distinctive differences in the assembly of the ribs and frame. The ship is decorated with carvings and painted designs on the bow and stern, often in vivid, bright colors. This image of the Thai junk is drawn from a replica based on line drawings found in Japanese trade records dating to the mid-19th century (source: the book Ships: The Culture of the Chao Phraya River Basin People).

Note: Trade by junk ships in the Chao Phraya River basin has evidence dating back to the (Sri) Dvaravati period, when it was a central state for trade with various countries in Southeast Asian waters. Trade continued through the Sukhothai, Ayutthaya, Thonburi, and early Rattanakosin periods (from the book Ships: The Culture of the People of the Chao Phraya River Basin, 2002: 15-16).

Foreign trade in early Rattanakosin used junk ships, called “samphea” or royal junks. During King Rama I’s reign, there were two royal junks: Hoo Song and Throne Letter Ship. Private junks belonged to high officials and merchants. It was said that Phraya Klang (Khun), later Chaophraya Rattanathibet, ancestor of the Rattanakul family, owned more junks than anyone else and was known as a wealthy samphea merchant.

Sethiakoset described the junk’s features: the bow had a “fish mouth” shape with centipede flags on both sides. Near the bow were white and black painted “eye spots.” The bow’s side was painted red with a lion-shaped board called “tapin” used to support the fish mouth. At the center was a white circle with more details. The stern was painted red with a white circle bearing the ship’s Chinese name. The captain, called “Junju,” had sole authority over the cargo. The navigation was the duty of “Ho Chang” or helmsman, and the “Tai Kong” held the rear position. Junks sailed into the gulf in groups of 3-4 ships around March-April with the northeast monsoon and departed around July-August with the southwest monsoon. Junk berths along the Chao Phraya River were near Khlong Ong Ang, westward, lined in two rows facing the river mouth. Newcomers were greeted with trumpet signals, and when it was time to unload, officials called Khun Thong Waree or Khun Phakdee managed the process. Sethiakoset recalled the tradition of “stepping on the junk’s head.” Sir John Bowring recorded that each junk carried tribute goods for the king and ministers.

Later, the junks functioned like department stores, with crew members selling various goods. Thais eagerly bought from them, with trade lasting two months until May-June-July, when the junks sailed mainly to China.

By King Rama III’s reign, the number of junks declined. He predicted their disappearance and ordered a pagoda built with a junk base at Wat Khok Krabue, renamed Wat Yannawa.

This prophecy came true when the last junk, Bun Heng, owned by Phraya Phisan Phonpanit (Jin Sue Phisanbut), sank in 1874. However, samphea trade continued, switching to Western-style steamships. Early difficulties entering China were solved by bamboo scaffolding and painting the steamships with junk-style “eye spots” so Chinese officials would permit trade. Later modifications combined a junk bow with a steamship stern, called “steamship of many ways,” locally known as “steamship buay,” facilitating trade with China even further (Barai, 2004:5).

9.2.2 Long-term measures to solve the famine and scarcity among the people were as follows:

King Taksin of Thonburi actively supported foreign trade, especially with China, due to shortages of essential goods within the country. Moreover, trade could generate significant profits. Therefore, promoting international trade was a key factor in restoring the kingdom’s economic status. King Taksin encouraged samphea trade and sent royal junks to trade with various countries such as China and India. At times, up to eleven royal junks were dispatched. The main exported goods included forest products, animal hides, tin, ivory, and logs (Suree Phumiphmon, 1996: 78-79). In addition, many foreign junks, including those from China and Java, came to trade with Thonburi. The profits from trade strengthened the kingdom’s economic foundation and helped reduce the burden of tax collection.

He established prosperity and well-being for the people and took measures to prevent future shortages, such as:

2.1 During the quiet winter season, when there was no warfare, he ordered the construction of roads to facilitate travel for merchants and commoners alike, promoting communication and commerce. Prior to this, road construction was rarely undertaken, marking King Taksin as a notably progressive monarch.

2.2 In years of drought and scarcity, such as in 1768 (B.E. 2311), when rice prices soared to 2 chang (approximately 160 baht) per cartload, he commanded officials to collectively cultivate off-season rice fields extensively to avoid forcing the populace into distress by having to compete for scarce food supplies (Sanun Silakorn, 1988: 36-37).

2.3 He also encouraged the cultivation of mulberry trees for silkworm farming, as well as the production of tobacco, balm, and lacquer to serve as export commodities (Suree Phumiphmon, 1996: 78-79).

Promotion of Rice Cultivation

When the country was peaceful and free from enemy invasions, the people began to resume their normal livelihoods, especially rice farming, which had been the main occupation of Thai society since ancient times. This activity received strong support and encouragement from the government at that time, significantly helping to alleviate the shortage of rice among the people.

Later, in 1771 (B.E. 2314), the King ordered a large-scale expansion of rice fields by converting garden areas into rice paddies on both sides outside the city moat—east side (Phra Nakhon side) and west side (Thonburi side)—which were called “Talay Tom” (Mud Sea). This area also served strategically as a buffer zone for setting up camps to defend against enemy attacks approaching the capital.

After the campaign against the northern city-states in mid-1776 (B.E. 2319) led by Chaow Hunki, the King summoned all armies to gather at Thonburi and ordered commanders and generals to lead their troops in rice cultivation.

For example, Chao Phraya Chakri, Chao Phraya Surasi, and Phraya Thamma were assigned to oversee the troops farming on the eastern side of Thonburi. Meanwhile, Phra Yommarat and Phra Yararatchsuphawadi cultivated rice at Krathum Ban, Nong Bang, in the Nakhon Chaisi district. The officials overseeing the troops’ farming worked in the area called Talay Tom outside the eastern city moat. During times free from warfare, soldiers were also encouraged to return to their hometowns to farm.

He commanded that people cease their duties at the fortifications and return to their native lands to cultivate rice fields… and since the Burmese did not pursue further, it was the season for planting. Thus, the armies in Phichit and Nakhon Sawan were dismissed.

Encouraging the populace to resume agriculture ensured sufficient food supplies for the kingdom. The agricultural labor force during the Thonburi period comprised not only Thai commoners but also captives from the Lao and Khmer peoples captured in territorial wars. For instance, in 1774 (B.E. 2317), about ten thousand Lao captives were taken; in 1778 (B.E. 2321), over ten thousand Khmer captives; and in 1779 (B.E. 2322), a large number of Lao people were resettled. These captives were settled in towns such as Phetchaburi, Saraburi, Ratchaburi, Chanthaburi, and the western frontier cities to cultivate the land. Moreover, some Chinese groups took up farming occupations, planting betel nut and pepper along the eastern seaboard and southern provinces (Sukhothai Thammathirat Open University, 2003: 359).

On the eastern side, cultivation extended continuously through the plains of Bang Kapi and Thung Sam Sen; on the western side, farming reached areas like Krathum Baen, Nong Bua, and Nakhon Chaisi district. Consequently, Bangkok became a significant new rice-producing region in central Thailand from that time onward.

In summary, as general conditions improved, King Taksin of Thonburi undertook various initiatives to nurture the realm and bring prosperity to the people, such as constructing roads to facilitate transportation.

The economic and social conditions during King Taksin’s reign were initially dire and in decline. The King endeavored to solve problems by alleviating shortages through the distribution of food and essential goods and revitalizing the economy via trade. He also facilitated increased immigration of Teochew Chinese, who were skilled in commerce, thereby diminishing the influence of the Hokkien community, which had been dominant since the Ayutthaya period (Suree Phumiphmon, 1996: 80). Furthermore, the King supported production activities, and thus the economy gradually improved and stabilized into the Rattanakosin era (Royal Biography and Activities of King Taksin the Great, published in the Funeral Memorial Book of Ms. Phan Na Nakhon, 20 September 1981: 6).