King Taksin The Great

Chapter 6: The Battles of King Taksin the Great Against Burma Before and After the Fall of Ayutthaya

In the year 1764 (B.E. 2307), Ayutthaya issued orders for Phra Ya Tak (Sin) and Phra Ya Phiphatkosa (Phra Ya Kosa Thibodi) to lead a land force to intercept the Burmese army at Phetchaburi. The Siamese forces engaged in battle with notable valor and succeeded in driving the Burmese back through the Singkhon Pass, forcing them to retreat to Tavoy. The Siamese army thus successfully defended and held the city of Phetchaburi. (Thuan Boonyaniyom, 1970: 35–36)

6.1 When the Burmese forces surrounded Ayutthaya (in 1766 A.D. / B.E. 2309), what position did King Taksin the Great hold? Where was he residing at the time?

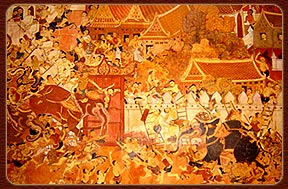

In the year 1766 (B.E. 2309), when the Burmese army surrounded Ayutthaya, King Taksin the Great, then known as Phra Ya Tak, was serving as a royal official under King Ekkathat. Recognized for his military acumen and bravery, he was later promoted to Phra Ya Wachira Prakan and appointed governor of Kamphaeng Phet. However, he never took up the post, as he remained engaged in defending the capital against the advancing Burmese forces. Prior to the fall of Ayutthaya, Phra Ya Wachira Prakan had been tasked with leading a campaign to resist the Burmese at Mergui but was unsuccessful and retreated to reinforce defenses within Ayutthaya. He eventually commanded a naval force and stationed his troops at Wat Pa Kaeo (now Wat Yai Chai Mongkhon) to block enemy advances into the city. According to the Burmese royal chronicles, the Siamese organized a major offensive in 1766 led by Phra Ya Wachira Prakan and Phra Ya Tan, fielding a force of 50,000 troops, 1,000 cannons, and 400 war elephants, while the Burmese under Mang Maha Noratha defended with 20,000 soldiers, 100 elephants, and 500 horses.

Military Engagement Near Phukhao Thong Stupa

The clash escalated into close-quarter combat. Initially, the Siamese forces launched a heavy artillery bombardment upon the Burmese troops. Following this, Phra Ya Tan (พระยาตาน) led a formidable charge of 400 war elephants, valiantly storming into the enemy lines. In the heat of battle, he engaged in a royal elephant duel with the Governor of Suphanburi, one of the local rulers who had sworn fealty to Burma. Before the outcome of the duel could be determined, the Governor of Suphanburi was struck down by a marksman’s bullet and died on the field.

Seizing the opportunity, Phra Ya Tan pressed forward with his elephants, breaking through the ranks of the Burmese cavalry and scattering them. At that critical moment, the entire Siamese force—comprising all 400 war elephants and artillery—executed a coordinated assault, wreaking havoc upon the enemy and driving the Burmese into disarray.

In response, General Mang Maha Noratha, the principal Burmese commander, was compelled to deploy his own elephant corps and artillery to stem the tide of the Siamese offensive. This maneuver succeeded in halting the momentum of the Thai assault and reversing the fortunes of battle in favor of the Burmese.

Thereafter, the Burmese army established encampments surrounding the capital on all four fronts. However, all encampments remained positioned at some distance from the city walls. Despite several attempts to breach the city, the Burmese were repeatedly repelled.

(Note: Burmese chroniclers often exaggerated the numerical strength of Siamese forces and downplayed their own, so as to magnify the valor and superiority of the Burmese troops, even when supposedly outnumbered. – Chanya Prachitromran, 1993: 116–117)

A Sketch Map Showing the Battle Positions of Phraya Thibet Pariyat, Phraya Tan, and Phraya Wachiraprakarn

(from the book The Fall of Ayutthaya in the Second Burmese Invasion, B.E. 2310)

The Harassing Raids by Foreign Volunteers and Siamese Soldiers (Ayutthaya, 1766)

During this period, foreign volunteer forces, alongside Siamese soldiers, launched frequent harassing attacks against the enemy. These irregular sorties served to disrupt and challenge the besieging forces in multiple engagements.

The Chinese: The four Chinese nobles—Luang Choduek, Luang Thongsue, Luang Naowachot, and Luang Lea-ya—along with a group of Chinese volunteers, marched out to attack the Suan Phlu camp. They engaged in fierce and intense combat.

The Europeans: The merchants of the city—Rit Samdaeng, Wisut Sakorn, Anton, and many other Europeans—volunteered to attack the Ban Pla Hed camp. They engaged in fierce and intense combat as well.

At that time, an English ship named Alangkabooni was trading in Siam and volunteered to assist in fighting the Burmese. The ship used its cannons to fire upon the Burmese at Thonburi. However, the Burmese responded with artillery from the Vichai Prasit fortress, forcing the English ship to retreat through Nonthaburi. The English fired cannon shots at the Burmese at Wat Khema but were unable to withstand the Burmese forces, ultimately fleeing out to sea by boat. (Athorn Chantawimon, 2003: 228)

The bandits included Muen Han Kambang, Nai Chan Suea Tia, Nai Mak Si Nuad, Nai Jon Yai and four other chief bandits with their followers. Phra Muen Sri Saowarak served as the commander.

The Athamat volunteered to attack the Pa Phai camp and fought multiple battles against the Burmese, with heavy casualties on both sides.

The “Khak” volunteers were Luang Sri Yot, Luang Ratchapimol, Khun Sri Worakhun, Khun Ratchanithan, and many other foreign mercenaries including the Cham, Malay, Javanese, and other foreign groups in large numbers. Phra Chula was their commander, leading the attack on the Ban Pom camp. The Burmese also had a mercenary commander named Nemyo Kung Narad who fought against Phra Chula, both sides suffering heavy losses.

The Mon volunteers included Luang Theking, Phra Bamroephakdi, Phra Piya, Phra Ram, along with many Mon from Sam Khok, Ban Pa Pla, and Ban Hua Ro.

The Lao nobles such as Saen Kla, Saen Han, Saen Tao, Wiang Kham, and a large number of Lao warriors also volunteered to attack the Burmese camps.

Subsequently, the authorities appointed Phaya Phon Thep to guard the city gates and oversee the city with absolute authority. Most of these volunteers mentioned were foreigners, with very few ethnic Thais left due to mass killings amid power struggles, including beheadings and systematic extermination that wiped out entire lineages. Many good men perished, leaving the Thai forces under Khun Luang Suriyamarit extremely weakened.

Note:

Regarding the settlements of foreigners during the Ayutthaya period, in the reign of King Rama V, Phraya Boranrajathanin once submitted a letter to Somdet Krom Phraya Damrong Rajanubhab concerning the locations where foreigners established their communities in Ayutthaya when it was still the capital city.

A schematic map showing the surprise attacks by foreign volunteer units and Thai soldiers in 1766 (B.E. 2309). (Image from the book The Fall of Ayutthaya, Second Time, B.E. 2310).

Brahmins lived in front of Wat Nang Muk, Wat Ammae, and Shee Kun, which were the locations of the Hindu shrines and the city pillar (Sao Ching Cha) in the city center.

Foreign Indians and Persian Indians resided from the Chinese Gate Bridge on the west side, past Wat Nang Muk, then turning toward Tha Gayi—locals called this area “Tung Kaek” (Indian Field).

Cham Indians lived along Khlong Ku Cham, south of Wat Kaew Fah.

Malay Indians lived along Khlong Takian downstream.

Makassan Indians lived on the west bank of the river, south of the mouth of Khlong Takian.

Chinese lived in several areas: behind Wat Chin to Sam Ma in Kai, near the Chinese Gate, at Khlong Suan Plu, at the mouth of Khlong Khao San, at Khlong Thanon Tan, at Ban Din, and on Ko Phra.

Japanese lived on the east riverbank, below Ban Suea Kham, north of Ko Rian.

Mon people lived in Ban Pho Sam Ton and at the mouth of Khlong Takian on the north side.

The Black-bellied Lao lived in Uthai District and the eastern side of Bang Pa-in District.

The White-bellied Lao lived along the Maha Brahma River outside the Khlong Pak Khu estuary.

The Shan (Thai Yai) lived at Ban Pom Nuea, Peniad.

The Vietnamese (Yuan) lived north of Wat Nang Krai, up to the northern side of Khlong Takian estuary.

The Tavoy (Tanaw) lived at Khlong Luang and Wat Prod Sat.

The Khmer lived along the southern bank of the Nakhon Chai Si River near Ngiu Rai and close to Wat Khang Khao.

The Portuguese lived along the west bank of the river, behind Ban Din.

The Dutch in Ayutthaya lived along the east bank of the river, south of Wat Phanan Choeng (and had a warehouse at the mouth of Khlong Bang Plakod by the Chao Phraya River near Phra Pradaeng, an area called New Amsterdam).

The English lived along the east bank of the river, south of the Dutch settlement, down to the north side of the Mae Bia River mouth.

The French lived at Ban Pla Hed, on the northern side of Khlong Takian estuary.

(Source: Athorn Chantawimol, 2546: 223)

6.2 What caused King Taksin the Great to become discouraged?

During the defense of the capital, although Phraya Wachiraprakan (Sin) commanded the battle and fought the enemy skillfully, he encountered several events that caused him great discouragement, namely:

- 1) In 1766 (B.E. 2309), Phraya Wachiraprakan led troops to attack and successfully captured the Burmese camp at Wat Prod Sat, but the commander responsible for defending the capital did not send reinforcements. Mang Mahanatha then sent additional forces, allowing the Burmese to retake the camp. As a result, Phraya Wachiraprakan had to abandon the camp and retreat. The Thai army was scattered and retreated into the city. Phraya Wachiraprakan was accused of wrongdoing for the defeat and dispersal of the army in this incident. (Prapat Trinarong, 1999:14)

- 2) By the twelfth month, when the fields were flooded, it was known inside the capital that the Burmese fleet was navigating through the flooded plains, seemingly to scout and prepare for the siege of the city from the east. King Ekathat then ordered Phraya Phetchaburi to lead one naval force, while Phraya Wachiraprakan (Sin) commanded the rear guard (reserve force). They stationed at Wat Pa Kaeo (now called Wat Yai Chaimongkhon) to intercept and attack the Burmese troops advancing through the fields.

When the Burmese army grew larger, Phraya Phetchaburi wanted to lead his naval forces out to attack. Phraya Wachiraprakan (Sin), seeing their forces were insufficient, advised Phraya Phetchaburi to observe the Burmese movements first. However, Phraya Phetchaburi ignored this and led the fleet out to fight near Wat Sangkhawat. The Burmese forces, being superior in number, surrounded Phraya Phetchaburi’s fleet and dropped black earthenware bombs into his ships, causing explosions and sinking them. Phraya Phetchaburi died in battle. The remaining troops were either killed or fled.

Meanwhile, Phraya Wachiraprakan (Sin)’s forces did not engage the Burmese and retreated to set up camp at Wat Phichai, which was previously Phraya Phetchaburi’s camp (located south of the current railway station). Since then, Phraya Wachiraprakan (Sin) never entered the capital again. Despite this, he was accused of negligence in battle, of abandoning Phraya Phetchaburi in combat, which caused him great disappointment. (Thuan Boonyanuyom, 1970: 39-40)

- 3) Three months before the fall of the capital, there was a shortage of gunpowder within the city. Therefore, an order was issued that any unit wishing to fire cannons must first obtain permission at the Sala Luk Khun (Judges’ Hall), because the royal ladies and palace attendants were very timid. (Wiset Chaisri, 1998: 304)

One day, the Burmese advanced from the east where Phraya Wachiraprakan was in command. Seeing the urgency, he ordered his troops to fire the cannons at the enemy without requesting permission at the Sala Luk Khun. As a result, he was charged and sentenced, but only given a reprimand because of his prior merits. (Prapat Trinarong, “The Reign of King Taksin the Great,” Thai Journal 20(12): October-December 1999:14)

(Image from the book “The Fall of Ayutthaya, Second Time, B.E. 2310”)

6.3 why did King Taksin decide to break through the Burmese siege and escape from Ayutthaya?

The Burmese army besieged Ayutthaya for about two years. Phraya Wichiraprakarn predicted that Ayutthaya would inevitably fall because the Burmese reinforcements were vast, but the city’s defense was weak. Moreover, the weapons and military equipment were not in a ready state and were deteriorating. The king himself did not seem to care or try to solve the situation, allowing events to proceed as fate willed. The people’s morale was broken and scattered (Thuan Boonyaniyom, 1970: 40). In addition, Phraya Wichiraprakarn’s army was severely lacking supplies. Continuing to fight would be tantamount to leading soldiers to die pointlessly. Therefore, he planned to break through the Burmese encirclement to gather food, manpower, and military equipment to later return and reclaim Ayutthaya. This course was deemed better than staying and dying senselessly.

(Opening Ceremony of the King Taksin Monument, Chanthaburi Province, 1999: 20; http://www.wangdermpalace.com/kingtaksin/thai_millitaryact.html, 22/11/45)

6.4 When did King Taksin lead his troops to break out from Ayutthaya?

Phraya Wichiraprakarn (Sin) decided to gather about 500 loyalists, both Thai and Chinese (according to the Thonburi Chronicle by Phan Chanthanoomart (Jerm), the number was slightly over 1,000). His fellow officers included Phra Chiang Ngoen, Luang Phrom Sena, Luang Phichai Racha, Luang Ratchasena, Khun Aphai Phakdi, and Muen Ratchasaneha (Thuan Boonyaniyom, 1970: 40). They marched out from the camp at Wat Phichai on Saturday, in the second lunar month, the 6th day of the waxing moon, Year of the Dog, Atthasak era, Chula Sakarat 1128, in the evening—corresponding to January 4, 1767 (three months before the fall of Ayutthaya). They broke through the Burmese enemy lines heading east (or southeast, Prapat Trinarong, 1981: 14) via Ban Hantra and Ban Khao Mao, as the Burmese had not fully encircled the city but had only set up camps at some distance with relatively few troops (http://www.wangdermpalace.com/kingtaksin/thai_millitaryact.html, 22/11/45; and Ayutthaya Chronicle, p. 69).

Phraya Tak gathered his followers and fled from Ayutthaya.

(Image courtesy of Muang Boran)

Pharadee Mahakhan (1983: 17-18) expressed his opinion regarding King Taksin’s departure from Ayutthaya three months before its fall as follows:

“According to the law on rebellion in military offenses, Section 40, King Taksin’s act of fleeing from Ayutthaya would constitute treason and punishable by death. However, since he managed to escape and three months later Ayutthaya fell to the Burmese, his charge of rebellion was nullified. Moreover, some scholars argue that King Taksin and his followers did not flee merely to save themselves but rather to regroup and muster strength to reclaim Ayutthaya and to revive and uphold Buddhism, as recorded in the Royal Chronicles in the Royal Handwriting edition, which states that upon his arrival at the district of Hin Khong and Nam Kao in the Rayong region…”

He consulted with his generals, officers, and troops, saying:

“Ayutthaya will surely fall to the Burmese. I shall gather the people from all the eastern towns and muster them. Then, I will march back to reclaim the city, restoring it as the capital once more. I will also nurture and support the monks, Brahmins, and the people who have nowhere to take refuge, providing them shelter and happiness. Furthermore, I shall revive the glorious and flourishing Buddhist religion as it was before. I will establish myself as their ruler, so that all people will respect and fear me greatly. Only then will the restoration of the kingdom be accomplished with ease…”

— (Royal Chronicles in the Royal Handwriting edition of King Mongkut, pp. 603–604)

6.5 After breaking through the Burmese army, where did King Taksin advance his forces?

When Phraya Wachiraprakan (Sin) (who later became King Taksin) and his followers left the camp at Wat Phichai, they encountered the Burmese forces stationed east of Wat Phichai. With fierce and swift action—characteristic of his infantry and cavalry troops—this force broke through the Burmese lines and advanced eastward.

Phanadi Mahakhan (1983: 18-19) proposed reasons why King Taksin the Great headed to recruit forces along the eastern seaboard as follows:

The reasons why King Taksin of Thonburi proceeded to gather troops along the eastern coast may be considered as follows:

The eastern coastal towns still had sufficient manpower, weapons, and provisions to gather forces and launch a campaign to reclaim Ayutthaya.

These towns were not on the Burmese army’s route, so they remained intact and unaffected by the Burmese, who were also unfamiliar with the area.

While Ayutthaya was under siege by the Burmese, Chinese merchants had shifted their trade to the eastern coastal region, especially around Chanthaburi and Trat. Once these merchants accepted his authority, King Taksin would receive financial support and easier access to weapons and food supplies.

The eastern coastal towns were not far from Ayutthaya and connected by waterways. King Taksin likely planned that by advancing his army covertly via waterways, he could reclaim Ayutthaya without alerting the Burmese. Additionally, if he faced defeat, retreat into Khmer territory was possible.

The Burmese did not relent in pursuing the forces of Phraya Wachiraprakan (Sin). The fighting was fierce, with both sides engaging while retreating. The battle only subsided late at night, during which a great fire broke out in Ayutthaya. The flames burned brightly and could be seen from a great distance. Phraya Wachiraprakan (Sin) reached Ban Pho Saowan (or Pho Sanghan; however, the Thonburi Chronicles by Chantanus states it as Pho Samhao or Pho Sanghan), likely very late at night. Early the next morning, he saw Burmese soldiers advancing toward the village, so he organized his troops to fight near the fields between the temple and the village. The villagers united with Phraya Wachiraprakan’s forces in a coordinated effort, ultimately winning the battle. Many Burmese were killed, and the rest fled back.

Note: According to oral tradition passed down, Teacher Jirawan Kongsomsaeng, the headmistress of Ban Pho Sao Han School, recounted that among the villagers, there was a brave woman named “Nang Pho” who fought valiantly at the forefront, fearlessly confronting Burmese spears and swords until she died in battle. After the fighting ended, King Taksin honored both the village and Nang Pho by naming the village “Ban Pho Sao Han” (Village of the Brave Pho). Today, the villagers have made a statue of Nang Pho as a memorial, so that future generations can remember her honor. This statue is located in Village No. 3, Ban Pho Sao Han, Pho Sao Han Subdistrict, Uthai District, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya Province.

Phraya Taksin and his followers managed to escape safely from Ayutthaya and could see the city’s flames burning in the distance. (Image from the book Bloodied Sword)

The statue of Nang Pho, Ban Pho Sao Han

(Image from the book War: History)

After achieving victory, Phraya Wachiraprakarn led his forces from Ban Pho Sao Han toward Ban Pran Nok, a distance of about 3 kilometers. They rested and reorganized their troops. While the Thai soldiers went out to gather supplies from nearby villages, a group of Burmese soldiers came from Bang Kang (the site where the old Prachinburi fortress was built), heading to Ayutthaya. The Burmese force consisted of about 30 cavalry and 200 infantry. When the Burmese soldiers encountered the Thai troops gathering supplies, they began to encircle and chase them. Some Thai soldiers fled back to Ban Pran Nok to inform Phraya Wachiraprakarn. Acting swiftly and skillfully, he ordered the Thai troops to form a “winged bird” formation, enveloping the Burmese on both flanks. Phraya Wachiraprakarn mounted his horse and, along with five trusted soldiers leading the charge, confronted the 30 Burmese cavalry who were traveling carelessly. When faced unexpectedly by Phraya Wachiraprakarn’s cavalry, the Burmese were thrown into confusion. Phraya Wachiraprakarn launched a rapid assault, causing panic among the Burmese troops. They fought while retreating and soon met the 200 Burmese infantry following behind. At that moment, the Thai infantry positioned on both flanks took the opportunity to launch a counterattack, forcing the Burmese to retreat with heavy casualties. The remaining Burmese either died or fled in complete disarray.

Note:

Ban Pran Nok (Pran Nok Village) was home to an old hunter named Tao Kham, who lived alone and made a living by hunting birds. The village likely had many birds, so Tao Kham often hunted them using a bow. The birds he caught were probably shared with the soldiers under Phraya Wachiraprakarn, who roasted and cooked them at that time. In the past, in rural areas, people with specialized professions were called by the animal they hunted—for example, someone who hunted wild chickens was called a “wild chicken hunter,” and someone who hunted rabbits was called a “rabbit hunter.” Since Tao Kham liked to hunt birds, he was known as the “bird hunter,” which became the village’s name. A statue of Tao Kham was also made. Phraya Wachiraprakarn created his heroic feat with five Thai cavalry soldiers fighting against 30 Burmese cavalry, along with infantry forces on both sides of roughly equal numbers. Ultimately, the Burmese were defeated and fled in disorder. This event took place at Ban Pran Nok on January 4, 1766 (B.E. 2309). From then on, cavalry soldiers marked January 4 every year as “Cavalry Day,” and a memorial was established at Ban Pran Nok, Village No. 2, Pho Sao Han Subdistrict, Uthai District, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya Province, on January 4, 1991 (B.E. 2534). Due to the importance of this village, the government named a village in Thonburi “Ban Pran Nok,” located near Ban Chang Lho and Ban Khamin. The victory by Phraya Wachiraprakarn included villagers who had been hiding from the Burmese and joined him. The village headman, known as “Nai Song,” also joined.

The statue of Tao Kham at Ban Pran Nok (image from the book War: History).

Khun Muen Phan Thanai of Ban Bang Dong did not believe the call to arms from Phraya Wachiraprakarn, so he did not join the resistance. Because of this, Phraya Wachiraprakarn subdued him by force and brought him under control before marching to Na Ngeang (present-day Ban Na District) in Nakhon Nayok Province. Phraya Wachiraprakarn gathered troops, elephants, horses, transport, and provisions and traveled through Nakhon Nayok city, entering the area of Ban Kop Chae (the site of the current Kop Chae checkpoint, which lies within Prachantakham District, near where the Prachantakham River flows into the Prachinburi River).

At the Kop Chae checkpoint on the east bank, Phra Kru Sri Maha Phot Khanarak, the abbot of Wat Mai Krong Thong, later recounted that the east bank, where the troops of King Taksin crossed, currently has an abandoned temple named Wat Kop Chae, though it is unknown when it was built—likely after King Taksin’s troops had crossed.

After crossing the river to the east bank, Phraya Wachiraprakarn ordered the supply bearers to travel across the fields toward Ban Mao Ram, Phai Khat, and Ban Khu Lamphan, all located at the edge of Thung Si Maha Phot. His forces marched last in the column. While approaching Ban Khu Lamphan, Burmese troops from Pak Nam Chao Lo (thought to be Pak Nam Yothaka) south of Prachinburi city pursued by land and water.

Hearing the drums, gongs, and seeing the Burmese army’s flags, Phraya Wachiraprakarn ordered the supply corps to hurry to safety first. He quickly arranged his forces, deploying ambush lines and the final firing line consisting of his strike troops. He chose reed and cane thickets as cover for the boundary and movement corridors.

At the same time, he sent about 100 soldiers into the fields to engage the Burmese, feigning retreat toward the hidden firearms. After a while of fighting, when the Burmese saw the Thai troops withdrawing, they pursued, only to be met with concentrated gunfire. Many Burmese fell, and those reinforcements arriving in two or three waves were also defeated and retreated in disorder.

Phraya Wachiraprakarn then led the ambush troops in pursuit, slaughtering many Burmese in the reed and cane thickets. Survivors fled in all directions, and the Burmese did not follow further.

Having finished the battle at Ban Khu Lamphan in Prachinburi territory, Phraya Wachiraprakarn reorganized his army and prepared to move south from Ban Khu Lamphan about six kilometers to camp at Wat Ton Pho, Ko Phib Subdistrict, Ko Phib District, Prachinburi Province.

On Monday, the 14th day of the second lunar month, Year of the Dog (B.E. 2309), Phraya Wachiraprakarn’s forces moved from Wat Ton Pho, passing through Mueang Chachoengsao (formerly Mueang Paed Riu), Mueang Chonburi (formerly Mueang Bang Pla Soi), and entered Ban Na Kluea. There, Nai Klam led his troops to obstruct Phraya Wachiraprakarn’s army, which responded by firing into the opposing forces. Nai Klam then yielded and submitted.

From Ban Na Kluea, the forces proceeded through Pattaya, Na Jomtien, Kai Tia, and Sattahip. From Sattahip, the troops marched along coastal villages past Ban Hin Dong and Ban Nam Kao, establishing a stronghold at Wat Lum (Wat Lum Maha Chai Chumphon or Wat Maha Chai Chumpuph), located in Ban Tha Du district, not far from the old camp that once was the city center of Rayong.

Note:

Phraya Tak (Phraya Wachiraprakarn) established a military camp at Wat Lum, in front of Rayong city (currently known as Wat Lum Maha Chai Chumphon). He then laid siege to the city of Rayong. Later, the people of Rayong built a shrine dedicated to King Taksin the Great for reverence and worship at the front of Wat Lum Maha Chai Chumphon, located in front of Rayong city to this day. Next to the shrine is a large satao tree called the “Satao of King Taksin,” as it was the tree under which King Taksin took shelter during his encampment, using its shade to protect from sun and wind.

Phraya Taksin advanced his troops, intending to besiege the city of Rayong.

At that time, it was customary to use monks as intermediaries or envoys to negotiate peace.

(Image courtesy of Muang Boran Museum)

This tree should be preserved and cared for as a memorial, much like the American Elm tree under which President George Washington once took shelter during the American Revolutionary War. The American people have maintained that elm carefully to this day, in remembrance of Washington’s merits and the tree’s symbolic support in securing victory and independence (Samanwanakit, Luang, 1953: 18). At Rayong city, the first governor was named Boon or Boonruang, known as Phra Rayong (Chusiri Jamraman, 1984: 69). He agreed to cooperate with Phraya Wachiraprakarn. However, another faction, composed of the old city officials including Luang Phonsaenhan, Khun Cha Muang, Khun Ram, and Muen Song, opposed Phraya Wachiraprakarn’s actions. They regarded his gathering of troops and invasion as an act of rebellion and aggression against the land and therefore refused to cooperate.

Later, the governor of Rayong hesitated but eventually allied with Khun Ram and Muen Song. Phraya Wachiraprakarn stayed for two days. On the night of the second day, Khun Ram and Muen Song, leaders of the Rayong forces, prepared to attack the old Rayong camp. Phraya Wachiraprakarn learned of their plan to strike at night and secretly made preparations. Phra Rayong himself held firm within the camp. When the forces of the city officials moved from the old camp to surround Phraya Wachiraprakarn’s camp, they shouted war cries and fired guns. In response, Phraya Wachiraprakarn extinguished all the fires throughout his camp.

Bringing thirty men from Rayong’s forces via Wat Noen, located north of Phraya Wachiraprakarn’s camp, they intended to break into the camp. When they crossed the bridge about ten meters from the camp, Phraya Wachiraprakarn’s soldiers fired volleys at Khun Ja Muang and his group, causing them to fall into the river. The following soldiers, frightened, fled completely. Seizing the opportunity, Phraya Wachiraprakarn ordered his troops to raise battle cries and advance, chasing the enemy. The Rayong officials’ forces fled into their old camp, but the pursuing soldiers caught up, slaughtered those inside, causing many deaths, and set fire to the camp. Thus, on that night, Rayong came under Phraya Wachiraprakarn’s control. At that time, Ayutthaya had not yet fallen to the Burmese. Phraya Wachiraprakarn’s attack on Rayong was viewed as a violation of the law, causing him to be cautious not to declare himself a rebel. He received the official title of Phraya Prasat, a chief governor, but his followers began calling him “Chao Tak” (Lord Tak) from then on. (Veena Rochanarata, 1997: 88)

During the period when Chao Tak held power in Rayong, Ayutthaya had not yet fallen. He established cooperative relations with various cities such as Chanthaburi, Chonburi, and Banteay Meas, all of which pledged to unite in resistance against the Burmese. However, after the fall of Ayutthaya, the local governors hesitated, contemplating declaring independence for themselves. Chao Tak therefore prepared to subdue these rebellious lords so that they could be united under a single command, enabling an effective campaign to drive the Burmese from the land. His first campaign targeted Khun Ram and Muen Song in Klaeng. Upon victory, he moved to Chonburi, where he persuaded Nai Thong Yu Nok Lek to join his cause and appointed him as Phraya Anurathaburi, also known as Phraya Anuratchaburi Si Mahasamut (Chusiri Jamraman, 1984: 90). (Later, King Taksin ordered his execution for misconduct.)

Note: Phraya Anuratchaburi Si Mahasamut, originally named Nai Thong Yu Nok Lek, was the governor of Chonburi. When King Taksin arrived in Rayong, he learned that Nai Thong Yu Nok Lek had conspired with Rayong officials to assemble forces to harm him. King Taksin planned an ambush, attacking their troops and scattering them. Nai Thong Yu fled to Chonburi but later surrendered and pledged allegiance, after which he was appointed Phraya Anurathaburi Si Mahasamut, governor of Chonburi.

However, it later became known that Phraya Anuratchaburi (Nai Thong Yu Nok Lek) behaved improperly, turning to piracy by raiding merchant junks. When King Taksin advanced his army toward the mouth of the Chao Phraya River and learned of this, he halted his march to investigate in Chonburi. Upon confirming Phraya Anuratchaburi’s guilt, he was executed. As for Nai Thong Yu Nok Lek, he was invulnerable to stabbing or cutting because his navel was made of copper. Therefore, he was bound and drowned in the sea.

(Department of Fine Arts, Royal Chronicles in Royal Handwriting Edition, commemorative printing for Khun Por Tailong Pornprapa’s funeral, 4 Sept 1968: 617)

The next crucial battle was the assault on Chanthaburi (formerly called Chanthaboon), a fortified city long important in the east. When King Taksin requested cooperation from Phraya Chanthaburi but failed, and instead was deceived by Phraya Chanthaburi’s ploy to kill him, a battle to capture Chanthaburi became inevitable. The Thai-Burmese war chronicles describe it as follows:

Phraya Chanthaburi suspected that King Taksin was angry and unwilling to ally with him, and might be seeking cause to attack Chanthaburi. He consulted with Khun Ram and Muen Song, concluding that fighting King Taksin directly would be difficult, since Taksin was skilled and his troops experienced. They therefore devised a plan to lure King Taksin into Chanthaburi, where he could be easily eliminated. Acting on this, Phraya Chanthaburi sent four monks as envoys to invite King Taksin to come down to Chanthaburi. The monks arrived in Rayong.

At that time, King Taksin was at Chonburi and waited until his return to Rayong. The monks then told him that Phraya Chanthaburi, angered by the enemy’s devastation of Ayutthaya, was willing to help Taksin overcome adversity and restore peace and prosperity. However, Chanthaburi was well provisioned, unlike Rayong, which was small and unsuitable for gathering a large army. Therefore, King Taksin was invited to establish his base in Chanthaburi to prepare for the campaign to retake Ayutthaya from the invaders.

Hearing this, King Taksin was pleased, ordered his troops to rest and recover, then sent the monks ahead to guide him to Chanthaburi. Upon reaching Bang Kra Ja Hua Waen, about 200 sen from Chanthaburi, Phraya Chanthaburi’s chief official welcomed them and informed King Taksin that preparations had been made for their camp by the river on the south bank opposite the city. King Taksin ordered his army to follow the official, but before reaching Chanthaburi, a messenger warned him that Phraya Chanthaburi was colluding with Khun Ram and Muen Song to amass forces inside the city to ambush his army during the crossing of the river south of the city.

King Taksin hastened to forbid his army from following Luang Palat to cross the river, instead ordering the troops to turn north and establish a camp at Wat Kaew, about five sen from the Tha Chang Gate of Chanthaburi city. Upon seeing that King Taksin did not cross as expected but instead positioned his forces along the city’s edge, Phraya Chanthaburi was alarmed. He quickly ordered his soldiers to man the fortifications and sent Khun Phromthiban, his water commander, along with several notable men, to meet King Taksin. They were to invite him to enter the city and meet with Phraya Chanthaburi. King Taksin instructed Khun Phromthiban to return and tell Phraya Chanthaburi that originally, Phraya Chanthaburi had sent monks as envoys to invite him for consultation, intending to cooperate in planning to restore Ayutthaya. King Taksin took this as a sincere invitation and came accordingly. Moreover, King Taksin himself had been the lord of Kamphaeng Phet, holding the rank of a senior noble, superior to Phraya Chanthaburi. Upon arrival, however, Phraya Chanthaburi did not come forth to welcome him but instead summoned troops to man the fortifications and allied himself with Khun Ram and Muen Song, who had twice defeated King Taksin before. Phraya Chanthaburi treated King Taksin as an enemy, making it impossible for him to enter the city. King Taksin therefore insisted that for him to enter, either Phraya Chanthaburi must come out to meet him personally, or Khun Ram and Muen Song be sent forth to swear an oath to prove their trustworthiness.

If such gestures were made, King Taksin said, he would then see the sincerity of Phraya Chanthaburi and would continue to regard him as a brother and ally. Khun Phromthiban returned to convey this message, but Phraya Chanthaburi neither came out nor sent Khun Ram or Muen Song. Instead, he merely sent food offerings and informed King Taksin that Khun Ram and Muen Song were afraid to come out, and Phraya Chanthaburi was at a loss how to compel them. King Taksin, displeased, ordered that this be reported back to Phraya Chanthaburi, saying that since he saw no goodwill, he would leave him to guard the city well. Seeing that his forces outnumbered King Taksin’s, Phraya Chanthaburi ordered the city gates closed and prepared the city’s defenses firmly.

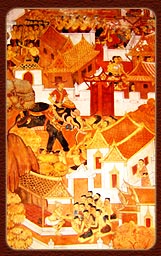

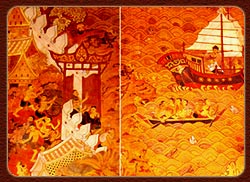

The army of Phraya Tak prepared to assault Chanthaburi city.

(Image courtesy of Muang Boran)

A portion of Phraya Tak’s army, filled with fervor and determination of the soldiers in the ranks.

(Image courtesy of Muang Boran)

The Royal Chronicles state:

“He commanded the generals, commanders, and all brave soldiers to cook and eat together,

then to pour out what remained until nothing was left.

This very night, swiftly assault the city of Chanthaburi and seize it.

Have your breakfast inside the city;

if you fail to capture the city, then all shall die together.”

(Image courtesy of Muang Boran)

…As a warrior, King Taksin immediately realized that he had to strike first to avoid defeat. So, he summoned his generals and commanders and ordered:

“We shall attack Chanthaburi tonight. Once the army has finished cooking and eating dinner, all the remaining food must be poured out, and the pots smashed. We shall have breakfast together inside the city tomorrow. If we fail to capture the city tonight, then we shall all die together.” The generals and commanders, having witnessed King Taksin’s power before, dared not disobey and carried out his orders…

The army of Phraya Taksin advanced to attack Chanthaburi, observing the houses of the people and the enemy forces preparing to approach the city.

(Image courtesy of Muang Boran)

Phraya Taksin’s army advanced to attack Chanthaburi (Chanthaburi city).

(Image courtesy of Muang Boran)

At night, King Taksin assigned the Thai-Chinese soldiers to stealthily enter the city without alerting the townspeople. He ordered them to listen carefully for the signal gunshot, which would indicate the time to simultaneously storm the city, but they were instructed to keep silent and avoid making any loud noises. Once any group successfully entered the city, they were to shout loudly as a signal for the other groups.

When preparations were complete, at the auspicious time of 3 a.m., King Taksin mounted his war elephant, Phankiribancha or Phankirikunchornchattan (Chusiri Jamman, 1984: 92), and fired a signal gun to order the soldiers to attack simultaneously from all sides. King Taksin then rode his royal elephant to break down the city gate. At that moment, the town’s defenders fired many cannons and small firearms in defense.

The mahout of the royal war elephant, perceiving the heavy cannon fire from the townsfolk, feared that King Taksin might be struck. Thus, he attempted to draw back the royal elephant. King Taksin, displeased, drew his sword and turned to strike the mahout. Startled, the mahout begged for mercy and then urged the elephant forward to break down the city gate. The soldiers poured into the city through the breach. Upon realizing that the enemy had entered, the townspeople abandoned their posts and fled in disarray. Meanwhile, Phraya Chanthaburi fled by boat with his family to the town of Banthaimat.

King Taksin’s capture of Chanthaburi occurred on Sunday, the 7th day of the 7th lunar month, Year of the Pig, 2310 BE (corresponding to 14 June 1767), two months after the fall of Ayutthaya.

According to the Siamese Junk Chronicle and the Legend of the Chinese of Bangkrok,

“…During the siege of Chanthaburi, King Taksin received assistance from a Chinese junk captain from Trat named Jeen, who was later appointed Phraya Aphai Phiphit, Governor of Trat…”

(Pimprapai Pisankul, 1971: 97) Having taken Chanthaburi, King Taksin persuaded the people to return to their homes, showing mercy toward those who had formerly resisted him. Once order was restored in Chanthaburi, he marched his army to Trat, traveling for seven days and seven nights. The officials and common folk, fearing his might, submitted peacefully throughout the city. At that time, several Chinese junks lay anchored at the mouth of the Trat River. King Taksin summoned the ship captains to submit, but they resisted and fired upon his envoys. Upon learning this, King Taksin himself boarded a warship and laid siege to the junks. He called for their surrender, but they refused and unleashed cannon fire. After half a day’s fierce combat, King Taksin’s forces captured all the junks, seizing a vast quantity of arms and goods. Having secured Trat, King Taksin returned to establish his encampment at Chanthaburi.

(Ruamsak Chaikomintorn, Lt. Gen., Phansuksarn, 2000: 18-26)

The Royal Chronicles record that “…Phraya Chanthaburi fled the city with his wife and children, sailing to the town of Phutthaimat. The combined Thai and Chinese troops captured his family and seized a great quantity of valuables, gold, silver, cannons—both large and small—and various arms and munitions. Thus, the siege was halted in the town of Chanthaburi…”

(Image courtesy of Muang Boran)

The route taken by King Taksin the Great and the battle sites”

(Image from the book Wars: A History)

Summary of Phraya Wachiraprakan (Sin)’s escape route from Ayutthaya: Camp at Wat Phichai – Ban Pho Sao Han – Ban Pran Nok – Nakhon Nayok – Prachinburi – Chonburi – Rayong – Chanthaburi – Trat – Chanthaburi

6.6Why did King Taksin the Great choose Chanthaburi as the place to regroup and recuperate his forces after breaking through the Burmese siege, prior to the fall of Ayutthaya? Why did He not choose to proceed to other cities instead?

The eastward course was chosen for several reasons. First, breaking through the Burmese to return to Tak was impossible, as many territories held by the Burmese lay in between. Even Tak itself was under Burmese control.

King Chulalongkorn speculated that Phraya Tak chose Chanthaburi because once past Chonburi and heading eastward, they would be beyond the reach of the Burmese, who would not pursue them further.

Chanthaburi was an important eastern coastal city, serving as a hub for communication and contact with other regions, such as southern Siam, Cambodia, and Phutthaimat.

Moreover, Chanthaburi’s location made it a suitable gateway for easy escape or further movement to other areas.

An important point often overlooked by historians is that Chanthaburi was a city where King Taksin (Somdet Phra Chao Krung Thonburi) had previously visited for trade during his time as a caravan leader stationed in Tak. The route from Tak to Ayutthaya passing through Chonburi, Rayong, and Chanthaburi was a path well known and familiar to him. Most significantly, Chanthaburi was home to a dense community of Teochew (Chaozhou) Chinese settlers who were likely acquainted with Phraya Tak, sharing a common Chinese heritage. Traveling to Chanthaburi thus meant returning to a land he knew well — a place where he could feel secure among familiar and trusted people. All these factors formed the rationale behind His Majesty’s choice of Chanthaburi as a place of recuperation and a base for assembling his forces.

(Nithi Eawsriwong, 1986: 69; “Lakamueang Chanthaburi lae Prawattisat Mueang Chanthaburi,” 1993: 61)