King Taksin the Great

Chapter 4: The 24th War Between Siam and Burma (1765–1767)

4.1 What was the nature of the Burmese army’s campaign this time?

It has been said that King Chulalongkorn (Rama V) was possibly the first to describe the Burmese army that invaded this time as a “bandit-like force,” meaning that the army lacked the strength to launch a decisive siege on the capital, instead resorting to raiding and pillaging the surrounding areas for three years before finally capturing Ayutthaya.

Somdet Krom Phraya Damrong Rajanubhab wrote:

“… The Burmese army was a bandit army, not a royal army. They lacked even a clear objective to capture Ayutthaya, as their original goal was merely to suppress the city of Tavoy. However, upon discovering the weakness of the Thai forces, they advanced to the outskirts of the capital. He did not accept the Burmese Royal Chronicles’ claim that the Burmese planned simultaneous invasions from the north and south converging on Ayutthaya, considering such an idea to be a later fabrication by the Burmese chronicles…”

(“Thai vs. Burma,” 1964: 311-314)

Sunet Chutintharanon (2000: 79-83) gave the following opinion:

“In the past, understanding of the war during the fall of Ayutthaya in 1767 within Thai academic circles has been limited to the notion that the Burmese army ‘came as bandits.’ That is, the invading forces did not come as a royal army; they were small in number, lacked prior planning, and upon seeing Ayutthaya weak, advanced in. Moreover, the northern and southern Burmese armies acted independently of each other.”

On the contrary, the Glass Palace Chronicle and the Konbaung Chronicle state that King Mangrai (Maha Mingalar) had orderly preparations for the invasion of Ayutthaya well in advance. King Mangrai even thought that the Ayutthaya kingdom had never before been so destined for utter destruction. Therefore, relying on only the army led by Nemyo Thihapate advancing from the Chiang Mai route would be insufficient for an easy victory. It was necessary to deploy the army of Maha Norahta to assist from another direction.

Stages of the War

The war can be divided into four stages:

Bandits raiding and plundering the various frontier towns

Siege of frontier cities and approach to the outskirts of the capital

Military operations during the rainy season and flood season

The fall of the capital (Janya Prachitromrun, 1993: 56)

Furthermore, both Burmese chronicles clearly state that the main Burmese armies advancing from Chiang Mai and Tavoy were led by their commanders themselves from the beginning. There was no division of forces into bandits sent in advance. Both Burmese armies, using their superior strength, swept through all important towns located along the northern and southern invasion routes, sparing no city.

Even Phitsanulok—which Thai historians generally believe was never captured by the Burmese—the Burmese chronicles mention that Nemyo Thihapate’s army advancing via the Chiang Mai route not only attacked Phitsanulok but also established a main command center there to plan the subsequent attack on the lower cities along the Chao Phraya river basin.

Importantly, both direct and indirect Burmese sources indicate that although Nemyo Thihapate’s and Maha Norahta’s armies advanced via separate routes, their operations were coordinated and mutually supportive. They conducted sequential actions aimed at encircling Ayutthaya into a desperate situation by destroying or occupying surrounding towns, thus cutting off any chance for reinforcements to come to the capital’s aid.

Phu Khao Thong Chedi Phu Khao Thong is a major stupa located approximately 2 kilometers northwest outside the old city of Ayutthaya. It stands at a height of 90 meters (2 sen 5 wa 1 khuep). The temple is situated on a hill, surrounded by floodwaters. Its significance lies in being an important strategic battlefield during the two Burmese invasions of Ayutthaya. After the second fall of Ayutthaya, the temple gradually became abandoned, yet the great stupa remained a significant Buddhist site, attracting pilgrims. This is notably mentioned in the poem Nirat Phu Khao Thong by Sunthorn Phu. The present-day stupa was restored during the era of Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram in 1956. (Image source: from the book “Ayutthaya and Bayinnaung with Kyawodin Noratha”)

Burmese sources also state that the army of Mahanoratha, which reached the outskirts of the capital before the forces of Ne Myo Sihabodi, did not recklessly besiege the city independently. Instead, they held their position and awaited Ne Myo Sihabodi’s army at the village of Kanni, north of Thigok. Only after learning that Ne Myo Sihabodi’s forces had advanced to the city outskirts did Mahanoratha’s army march out from Kanni and position itself behind the Phu Khao Thong Great Chedi (Burmese chronicles refer to this stupa as the one built by King Hongsawadi, the White Elephant).

Note:

N. Na Paknam described Mahanoratha’s camp at Thigok as the only one of significant size, comparable to a city. He wrote:

“Because the river bends here form a horseshoe shape (this is where the Chao Phraya and Noi Rivers meet), the Burmese established their camp at Wat Thigok, building a strong brick wall cutting across the end of the horseshoe to both sides of the river. Though the bricks have since been almost entirely removed by locals to sell, the Thigok camp is historically renowned. It covered several dozen rai of land, with elephant and horse mounds, resembling a city in all respects.”

This is evidence that the Burmese invasion was not a mere bandit raid without strategic planning. The choice of terrain for the camp and the surviving fortifications indicate that the Burmese prepared for a prolonged campaign and had solutions for the flood season. Their primary objective from the beginning was to capture Ayutthaya and conquer the kingdom (Wiseschaichri, 1998: 202).

More importantly, both the Horkaew and Konbong Burmese chronicles vividly depict that during the second fall of Ayutthaya, the city’s rulers prepared and fought fiercely, contrary to the common misconception of weakness or disarray.

The Burmese chroniclers narrate the military strategy that the Ayutthayan king intended to employ in that war through a dialogue between Phaya Thibeth Priyat (Phaya Kuratit) and King Ekatat (the Burmese chronicles record King Ekatat’s name in Burmese; translated as King Ekatat Racha of Ayutthaya). Phaya Thibeth Priyat reported that the Burmese armies invading from both directions were not only vast in numbers but also confiscated elephants, horses, weapons, and supplies from towns in the east, west, and north. Thus, if the Burmese were allowed to establish permanent siege camps for a prolonged campaign, it would be difficult to defeat them. Therefore, Ayutthaya should seize the opportunity to strike before the Burmese fully entrenched themselves.

The Ayutthayan king responded that even if the capital did not send out troops to attack the Burmese—who were then positioned north and west of the city—when the flood season arrived, the Burmese would be forced to retreat. Only then would it not be too late to send forces to pursue and defeat them, capturing their spoils and prisoners.

The Burmese chronicles also describe several instances where the city’s defenders fiercely resisted, launching volleys of arrows and gunfire to prevent the enemy from approaching the city walls. Because of this, Mahanoratha proposed to his generals that the siege of Ayutthaya should employ the tactic used by Mahawthata to abduct Queen Pancala Candi: digging tunnels into the city of Pancala Raja. This tunnel-digging tactic was eventually implemented, as it offered a way to evade the defenders’ gunfire. Burmese sources state that five tunnels were dug. On the day Ayutthaya fell, the Burmese set fire to the tunnel foundations under the city walls, burning the supports until the walls collapsed. The Burmese then used ladders to scale the breached walls, while other forces infiltrated through three of the prepared tunnels.

The chronicles further record that as soon as Burmese troops entered the capital, they spread out to set fire to houses and temples, seize valuables, capture prisoners, and loot according to their desires.

4.2 Did the Thais adequately prepare and concentrate their forces to defend the capital city of Ayutthaya, or not?

In the past, Ayutthaya was defended by a city wall made of brick and quite tall, surrounding the expansive city. This made it possible to effectively prevent enemy forces from launching direct attacks. Although the Burmese army besieged the capital, the city’s defense was strong and resilient. However, the strategy of relying on the capital as a fortress for enemies to surround and wait for reinforcements from provincial forces to flank them had long become ineffective. The new defensive strategy, employed by King Naresuan the Great, was widely accepted — namely, to push back the enemy before they could reach the city’s outskirts.

— Nithi Aiwsriwong (1997: 137)

Sunet Chutintharanon (2000: 189–191) commented:

“The strategy of using the capital city itself as a defensive base remained the fundamental tactic in wars against the Burmese during the late Ayutthaya period, such as during the 1759–60 Burmese–Siamese War and especially during the 1767 Fall of Ayutthaya. Burmese chronicles, including the Hokkew and Mannan Maha Yazawin, and the Konbaung royal chronicles, all consistently state that King Ekathat of Ayutthaya secretly planned to delay the Burmese siege until the flood season. Once the floods forced the Burmese to retreat, the Ayutthaya forces would counterattack to reclaim loot and prisoners.

This 1767 war reflects the advanced development of the defensive strategy using the capital as a base in the history of Thai–Burmese warfare, as it was the first and only time Ayutthaya’s leaders successfully held the city until the flood season as planned. The city itself remained relatively unscathed, and the residents sheltered inside the walls did not suffer severe food shortages.

The effective establishment of a “battlefront” prevented the Burmese forces, which had besieged the city for at least 10 months since February 1766, from even approaching the city walls or setting up artillery camps near the walls as they had in earlier wars like the 1759–60 conflict. The Burmese could only camp at a distance, such as near Wat Tha Kharong on the west side, while most of their forces were stuck in the fields of Prachet and Phu Khao Thong. On the southwest side, the Burmese did not reach Wat Chaiwatthanaram because the Ayutthaya forces had established large camps there. On the east side, they did not reach Wat Phichai. The entire moat area from Hua Ro to Pak Nam Mae Bia and Khlong Suan Phlu likely remained free of Burmese occupation. The southeast and south areas from Khlong Suan Phlu, Wat Portuguese, to Wat Phutthaisawan and Wat Saint Joseph remained under Thai control. From the north, the Burmese advance stopped near Pho Sam Ton and Pak Nam Prasop.

Phaya Boran Ratchathanin wrote:

“… When the Burmese laid siege to the capital, capable commanders led troops against the enemy. However, Thao Phra Ya Senabodi was a commander who did not engage in battle like Phaya Yommarat, who commanded at Nonthaburi. When the Burmese captured Thonburi, British mercenaries retreated, and Phaya Yommarat withdrew without fighting. Phaya Phra Khlang, commanding 10,000 men, marched out to attack the Burmese camp at Wat Pa Fai, Pak Nam Prasop. The Burmese fired cannonballs, killing 4–5 Thai soldiers, forcing the army to withdraw. Two or three days later, orders were given to attack the Burmese camp at Pak Nam Prasop again. Before the battle started, the Burmese tricked the Thai troops, ambushed, and killed many soldiers, causing the main Thai force to collapse back into the city.”

— Tuan Boonyaniyom (1970: 37)

Regarding naval warfare, royal chronicles recorded that when those inside the city realized the enemy artillery could reach the capital, they sent the navy to attack the Burmese camps. The naval force consisted of six volunteer regiments. It was said that Nai Rerk wielded a two-handed sword, performing a ritual dance at the front of the boat. When the Burmese fired, Nai Rerk was shot and fell into the water, causing the navy to retreat entirely back into the city.

It is considered that the belief in occult practices was the cause. Nai Rerk was apparently a master who performed a ritual sword dance in front of the army, believed to protect and safeguard the entire force. When the master was killed by a cannonball, the navy forces lost morale. Those commanding the troops saw that continuing the fight would only lead to death, so they ordered a retreat. This serves as a cautionary tale showing that excessive superstition and belief in occult practices can lead to failure. Tuan Boonyaniyom (1970: 39)

A French priest summarized the capability of the Thai soldiers defending Ayutthaya as follows:

“… Whenever the Thais went out to fight the Burmese, it was only to supply weapons to the enemy …” Nithi Aiwsriwong, in the funeral book for Major General Sawat (Udom) Panyasuk, 21 May 1997: 140

When the rainy season arrived, the Burmese generals complained to Mahanoratha that the heavy rains and impending floods from the north would make continuing the war very difficult. They requested to withdraw the troops temporarily and return to attack Ayutthaya again in the dry season. Mahanoratha disagreed, stating that Ayutthaya was already running low on food supplies and gunpowder, making it weak and nearly ready to be captured. Meanwhile, the Burmese forces had prepared by cultivating fields and gathering provisions. If they withdrew now, the Thais would have an opportunity to recruit more forces, better prepare their defenses, and it would not be as easy to conquer the city on a subsequent attack. Therefore, Mahanoratha refused to retreat. He ordered his troops to scout elevated grounds such as hills and temples around the capital and to divide forces to set up camps for the flood season. He also instructed that elephants, horses, and transport animals be sent to graze on higher lands in nearby towns. Additionally, he ordered the collection of many large and small boats to be used in the army’s operations.

(Image from the book The Fall of Ayutthaya, Second Time, B.E. 2310)

When the Burmese army completed their preparations for warfare during the rainy season and the flood period, Mahanoratha fell ill and passed away at the camp in Sikuk. However, Mahanoratha’s death ultimately worked to the disadvantage of the Thai side. Previously, the northern Burmese army and the southern Burmese army often competed and acted independently without subordinating to each other. After Mahanoratha’s death (according to Burmese sources, he likely died around late December B.E. 2309 or early January of the following year), Ne Myo Sihabodi became the supreme commander in sole charge of the entire army. This resulted in the northern and southern Burmese forces joining together to besiege Ayutthaya. Ne Myo Sihabodi moved his camp from Paknam Prasop to Pho Sam Ton camp.

(Tuan Boonyaniyom, 1970: 36–37)

Considerations

Thai chronicles consistently state that Mahanoratha died of fever, but the timing varies greatly, as if he had died before the flood season. The book History of Siam by Turpin records that Mahanoratha’s death occurred five days after the Thai envoy returned from negotiating peace.

(Sunetra Chutintharanon, 1998: 63)

Some have claimed that Ne Myo Sihabodi, who had a prior conflict with Mahanoratha, was responsible for his death.

Between Mahanoratha and Ne Myo Sihabodi, Mahanoratha held absolute decision-making power, even insisting on besieging the city during the flood season and endorsing the tactic of digging underground tunnels to capture the capital. Although there was discord between the two, there is no evidence of lack of coordination between their forces; on the contrary, they continuously supported each other. Therefore, Mahanoratha’s death did not change the situation of Ayutthaya at all.

At the beginning of the war, we divided the conflict into four stages. The first stage is called “Bandits plundering various towns.” Although it sounds like an accusation against only one side, it turns out that the Burmese themselves acted exactly as the term suggests, confirming the shared understanding rather than a one-sided allegation.

(Janya Prachitromrun, 1993: 175–176)

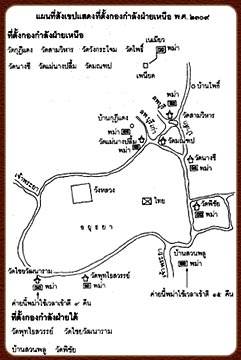

Around the capital, Ne Myo Sihabodi ordered the vanguard to set camp at Wat Phu Khao Thong, then at Wat Tha Karong, and established further camps extending down to Wat Kra Chai, Wat Plap Pha Chai, Wat Tao, Wat Surin, and Wat Daeng on the western side, positioning artillery to bombard the city.

Thai Defensive Camps

Subsequently, the Thai side ordered the establishment of defensive camps surrounding the capital as follows:

North: Camps set at Wat Phra Meru and at Pheniad

South: Camps set at Ban Suan Phlu under the command of Luang Aphai Phipat, a Chinese noble, overseeing 2,000 Chinese soldiers (some sources call them “nai kai” or commanders). The Christian community set up camp at Wat Phutthai Sawan.

East: Camps set at Wat Ko Kaeo, Wat Montop, and Wat Phichai under the command of Phraya Wachiraprakarn (Sin)

West: The Sixth Volunteer Regiment set camp at Wat Chaiwatthanaram

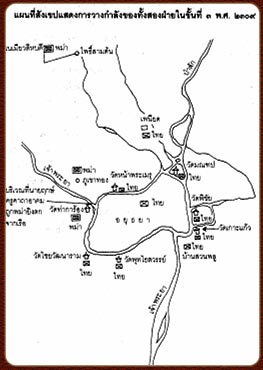

(Image from the book The Fall of Ayutthaya, Second Time, B.E. 2310)

The Thai army defending the capital began to break apart, as it became clear they had no chance to defeat the Burmese. The Chinese soldiers in the army, who had set up camp at Ban Suan Phlu, planned to save themselves first. About 300 men conspired to go to Phra Phutthabat to strip the gold covering the small mondop and the silver plates flooring the large mondop, dividing the loot among themselves as a form of personal gain. They then set fire to the mondop at Phra Phutthabat, hoping to cause destruction.

(Lieutenant General Ruamsak Chaikomin, “King Taksin the Great, Supreme Thai Marine”, in Special Veteran’s Issue: Veteran’s Day, 3 February 1994: 17)

Later, the Chinese camp at Ban Suan Phlu fell to the Burmese. Soon after, the Burmese advanced and attacked the camp at Pheniad, where Ne Myo Sihabodi, the Burmese commander, established his position. The Burmese army attacked the Thai camps set up to defend the northern side of the capital, and all these camps were routed and forced to retreat back into the city.

The Burmese established camps close to the capital on the north side at Wat Kudi Daeng, Wat Sam Phihan, Wat Sri Pho, Wat Nang Chi, Wat Mae Nang Pluem, and Wat Montop. They built watchtowers, mounted cannons, and fired into the capital daily without fail. Meanwhile, the southern commander advanced to attack at Wat Phutthaisawan, then moved to assault the camp at Wat Chaiwatthanaram. After eight to nine days of fighting, the Burmese succeeded in capturing the camp. (Lieutenant General Ruamsak Chaikomin, 1994:18) However, at the camp of Phraya Taksin at Wat Phichai, Phraya Taksin abandoned the camp before the Burmese could attack.

Wat Phanan Choeng, located at the confluence of the Pa Sak–Lopburi Rivers and the Chao Phraya River,

known as Bang Kaja whirlpool, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya Province.

(Image from the book “Social and Cultural History of Siam and Thailand”)

Phra Chao Phananchoeng, the principal Buddha image enshrined in the main vihara of Wat Phanan Choeng, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya Province.

According to the Royal Chronicle by Luang Prasoet Aksonnithi, the image was created 26 years before the establishment of Ayutthaya as the capital,

indicating that it is a significant temple dating back to the time of Ayodhya Sri Ramthep Nakhon.

(Image from the book “Social and Cultural History of Siam and Thailand”)

Omens of Doom (from the Royal Chronicle of the Old Capital, page 175)

As the fall of Ayutthaya drew near, ill omens began to manifest throughout the city. The great Buddha image at Wat Phananchoeng (Phra Chao Phananchoeng) was seen with tears flowing from its eyes. The sacred image of Tilokanat, carved from the wood of the Bodhi tree, was found with its chest split into two halves. The life-sized golden Buddha and the Phra Phuttha Surin, cast in red gold, enshrined within Wat Phra Si Sanphet in the Royal Palace, both displayed signs of desecration—their skin tarnished, and in one case, both eyes had fallen into its lap.

Two crows were seen fighting in the skies—one flew and plunged into the pinnacle of the chedi at Wat Phra That, its body impaled upon the spire as though placed by unseen hands. The statue of King Naresuan shed tears and let out mournful cries. Lightning struck the city on several occasions. The royal family and high officials had forsaken righteous conduct, signaling the fall of Ayutthaya through many such portents.

Within the besieged capital, as the Burmese army encircled the city for a long time, provisions grew scarce. Banditry and looting became rampant. Then, on Saturday, the 4th waxing moon of the second month in the year of the Dog (which corresponds to January 4, 1766), a great fire broke out in the city by night. It began at Tha Sai by the northern wall, spreading through the Khao Ploek Gate, igniting homes in Pa Maprao, and sweeping through Pa Thon, Pa Than, Pa Tong, and Pa Ya, consuming Wat Mahathat, Wat Ratchaburana, and reaching as far as Wat Chattathan. The blaze devoured monasteries, temples, and over 10,000 dwellings within the capital.

The people, now desperate and famished, suffered greatly. King Ekkathat dispatched envoys—Phra Ya Kalahom and members of the royal council—to the Pen Yat Camp, requesting a ceasefire and offering to become a tributary state to King Hsinbyushin. But Nemyo Thihapate, the Burmese general, rejected the proposal, desiring instead to plunder Ayutthaya completely.

The Burmese chronicle states that Nemyo Thihapate launched repeated assaults upon the capital but was repelled each time. The Thai defenders, driven by desperation, fought with valor and resisted every attempt, forcing the Burmese to halt and maintain their siege. However, famine within the walls pushed many to scale the walls and flee—some escaped successfully, while others surrendered themselves to the enemy in exchange for food.

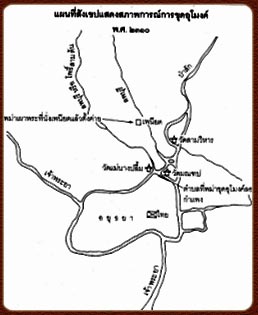

Seeing that the city was weak and disordered, Nemyo Thihapate ordered the forces at Wat Khudi Daeng, Wat Samphiran, and Wat Mondop to combine and advance at night. They constructed a woven raft bridge (saphan rueak) across the narrow river at Hua Ro, near Pom Maha Chai, at the northeast corner of the city. Sugar palm trunks were used to build approach ramparts (khae wihanlan) on both sides to shield the Burmese soldiers from Thai cannon fire as they advanced. The raft bridge was then drawn across the moat to the city wall.

Within the capital, upon seeing this bold maneuver, King Ekkathat commanded Chao Phraya Si Sarnrak to lead a sortie and attack the Burmese as they built the bridge. The Burmese records state that the Thais fought fiercely, driving the enemy into retreat, inflicting many casualties, and capturing another Burmese encampment. However, lacking sufficient reinforcements, the Thai forces were eventually driven back. From that point on, they ceased further offensives.

Once the Burmese completed the raft bridge, they established a new encampment at Sala Din, just outside the city. They then began digging underground tunnels, reaching the foundations of the city wall. Firewood was heaped beneath the wall’s base, and ladders were prepared to be placed upon the wall, ready for the final assault and plundering of the city.

The Tunnel Excavation (Ayutthaya – Hua Ro, 1766)

The plan to excavate tunnels began after the Burmese commanders had become fully convinced that the forces of Ayutthaya were greatly weakened, and that the inhabitants inside the city were suffering from severe famine. Upon confirming this situation, they resolved to begin tunneling operations beneath the city walls, specifically targeting the Hua Ro sector, which was known to be the narrowest part of the city moat. In total, five tunnels were excavated. Of these, two tunnels were dug to stop directly beneath the foundations of the city wall. From these points, horizontal extensions were created in both directions, running parallel to the wall for approximately 350 yards. Wooden beams were then installed underneath to support the structure of the wall above. The remaining three tunnels were dug beneath the foundations and into the inner part of the city. However, a layer of earth approximately two feet thick was intentionally left to seal the tunnels, awaiting final assault orders. The execution of this tunneling operation did not proceed smoothly. Thai defenders stationed on the ramparts of the city walls consistently opened fire upon any Burmese troops who ventured close to the wall. Because of this, the Burmese had to conduct their operations in stages, implementing strategic caution throughout the excavation process.

(Image from the book The Fall of Ayutthaya, Second Time, B.E. 2310)

The Construction of the Bridge, Initially, a bridge was constructed across the moat. Following that, the Burmese forces established three new camps adjacent to the northern moat of the city. Once the camps were completed, tunnel excavation commenced. The Konbaung-era Burmese chronicles state that the Thai side did not remain idle in the face of these operations. In this account, Phra Maha Montri (identified in Thai-Burmese Wars as Chamuen Sri Sanrak) volunteered to lead an attack on the three newly established Burmese camps. King Ekkathat thus authorized the deployment of 50,000 troops and 500 war elephants. It is recorded that Phra Maha Montri fought valiantly, managing to capture all three enemy camps. However, Burmese reinforcements were quickly dispatched and encircled the Thai forces, eventually forcing Phra Maha Montri to withdraw back into the capital. The Ayutthaya Royal Chronicle, by contrast, offers only a brief mention of this same event, stating that the Burmese forces advanced to burn the Pen Palace, established camps at Pen Yat, Wat Sam Viharn, and Wat Mondop, then constructed bridges over the embankments, awaiting the opportunity to tunnel beneath the city wall. Additional positions were fortified at Sala Din Fort, Wat Mae Nang Pluem, and Wat Si Pho, where they erected elevated platforms to mount cannons aimed into the city.

Considerations:

The strategy employed by the Burmese forces in this campaign was to lay a prolonged siege on the capital, showing no intent to retreat even during the flood season. The plan was executed with deliberate measures as follows:

Seizing and stockpiling provisions from the surrounding area as much as could be found, for long-term sustenance.

Gathering cattle and buffalo, and engaging in cultivation of nearby fields to maintain a food supply.

Sending elephants and horses to graze in areas rich in forage, to preserve the strength of their transport and cavalry.

Constructing fortresses and encampments in elevated areas safe from seasonal floods for the soldiers maintaining the siege.

Stationing patrol and guard units at intervals between forts to ensure defense continuity.

Interception of any external reinforcements, should allied forces attempt to break the siege.

2. The final assault strategy upon the capital saw a notable shift in Burmese tactics — from the former method of placing ladders to scale the city walls, to the more covert and calculated method of tunneling beneath the fortifications. The operations were executed in systematic stages, as follows:

- The construction of bridges,

- The establishment of fortified encampments,

- The excavation of underground tunnels.

It has been stated in certain records that the Burmese constructed three new fortified camps near the northern moat of the capital, with the intent of diverting the Siamese defenders’ attention from their covert tunneling operations. However, such details are notably absent from the Konbaung Chronicle.

The construction of these three forts served three primary strategic purposes:

To coordinate with the tunnelers, ensuring that Burmese soldiers digging beneath the walls would not be easily targeted by Siamese forces atop the battlements.

To intensify bombardment of the inner city and thereby inflict greater damage upon the defenders.

To support the infantry forces in their assault—whether by scaling the walls or entering through the tunnels—into the heart of Ayutthaya.

The military strategy employed by the Burmese in this campaign was to encircle the capital, thereby placing it in a state of isolation, compelling the inhabitants to rely solely on their own dwindling resources. The objective was clear: to prevent reinforcements from provincial cities from reaching and rescuing Ayutthaya.

Furthermore, the Burmese were determined not to allow natural seasonal conditions, such as floodwaters, to hinder their assault—a stark departure from earlier invasions. The defenders of Ayutthaya had not anticipated that the Burmese would successfully adapt to the challenges posed by the rainy season. Unbeknownst to them, the Burmese had come prepared with a naval division, skilled engineers, and the materials necessary to construct and launch vessels, thereby withstanding attacks from the Siamese navy, who sought to capitalize on the floodwaters.

The Burmese chronicles describe these naval engagements in vivid detail, noting that the Siamese navy, though formidable in both quality and quantity, was unable to overpower the Burmese response.

Thus, it becomes evident that what Siamese strategists failed to foresee—and could hardly have predicted—was the Burmese adaptation of their war strategy, which deliberately neutralized the disadvantage of natural obstacles. Even when the floodwaters rose, the Burmese maintained their siege with tenacity, leading Ayutthaya to suffer from famine and depletion, and ultimately to fall in defeat.

King Mongkut study : Reflecting from history, Reinventing our future

- 3. The fact that enemy forces had come close to besieging Ayutthaya was already a serious threat, and on top of that, a fire broke out, burning many houses. The existing scarcity and shortages worsened significantly. The people suffered greatly, as over 10,000 houses were destroyed by fire, leaving tens of thousands homeless. Seeing that the people were facing death, homelessness, and lack of food, their morale and physical strength declined. Therefore, King Ekathat sought to negotiate with the Burmese to cease the fighting and accept vassalage to the King of Ava. However, the Burmese commanders refused to relent, intending to plunder all the wealth and possessions of the people completely.

- 4. The Burmese firmly maintained their original objective in this battle from the beginning until now, even though the war could have ended. The Thai side, seeing the situation was hopeless, decided to surrender and become a vassal state, as had been done since ancient times. However, the Burmese refused to accept this, because Thailand’s surrender was not the aim of the Burmese. The Burmese intended to seize the wealth and people of Thailand, rather than merely making Thailand a vassal. Therefore, when Thailand surrendered and offered vassalage, the Burmese ignored it, as the Thai proposal was not aligned with the original Burmese goals.

- 5. The final assault as the city neared its fall, the Burmese carried out the following operations:

Condition of the Thai side: The Thai forces were completely weakened.

Location: At the edge of the Mahachai fortress, beside the northeastern corner of the city—where the river was narrower than elsewhere.

Time of operation: Nighttime

Operation: Palm wood was used to build defensive camps to block cannon fire, then they constructed a rafts bridge.

Counterattack: The Thai side was able to strongly repel the attack.

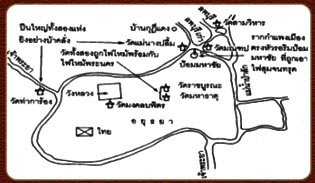

6. Fall of the city — operations as follows:

Location: At Hua Ro, by the rim of Mahachai Fortress

Time of operation: Started at 3 PM, and the Burmese entered the city at 8 PM on April 7, 1767 (B.E. 2310)

Operation: The Burmese completed the bridge, dug a tunnel lengthwise under the wall’s foundation, then set fire beneath the wall. The wall collapsed at 8 PM. The Burmese used ladders to climb into the city through the collapsed section first.

Duration of siege: The Burmese besieged the city for 1 year and 2 months.(Janya Prachitromrun, 1993: pp. 170–171)

Map of the situation at the fall of the city, B.E. 2310 (1767)

(Image from the book The Fall of Ayutthaya, Second Fall, B.E. 2310)

4.3 How did the second siege of Ayutthaya differ from the first siege of Ayutthaya?

The loss of independence of Siam (Ayutthaya) in this period has been interpreted by historians as a result of the differences between the Burmese invasions during the reigns of King Hongsawadi Bayinnaung and King Mangra.

During the reign of King Bayinnaung of Hongsawadi, when he waged war as a monarch, Ayutthaya experienced its first loss of the city to Burma, but the damage was not severe. This was because Bayinnaung’s wars aimed more at creating unity within the Pagan Empire of Burma rather than engaging in warfare solely for looting and destroying the enemy’s lands. (Piset Jiajantapong, 1999: 3560)

However, during the reign of King Mangra of Ava, the Burmese waged war more like bandits (Thuan Boonyaniyom, 1970: 57). Lacking the strength to directly assault the capital, they resorted to raiding and plundering the surrounding areas for about three years before finally capturing Ayutthaya. The Burmese royal chronicles from the Ho Kaeo manuscript are considered more reliable than what Thai historians have previously thought (Tin Ohn, “Modern Historical Writing in Burmese, 1724-1924,” in D.G.E. Hall, Historians of South-East Asia, Oxford University Press, 1962). At least the Burmese chronicles have been more thoroughly checked against primary sources, and in fact, Burmese records do not contradict the points mentioned in the Thai royal chronicles themselves.

The reign of King Mangra began with continuous suppression of rebellions in various regions. The traditional intervention of Ayutthaya in the spheres of influence under the Alaungpaya dynasty effectively encouraged these rebellions in the Burmese provinces. For this reason, it was necessary for King Mangra to reduce the power of Ayutthaya. The true objective of this war was not to expand royal authority by conquering Ayutthaya as a city-state but rather to cause the Ayutthaya kingdom to disintegrate or weaken to the point where it could no longer serve as a refuge for the Burmese vassal states.

According to the understanding of the old city people, the refusal to hand over Htutongja (Hui Tong Cha) to Burma when requested was the cause of this final war (Testimony of the Old City People, 1967: 167), which is not far from the truth when considering the overall relationship between Thailand and Burma.

The Burmese army that marched in since 1764 (B.E. 2307) had no king as its commander. Because of this, it was often disparaged as not being a royal army. However, the notion of what constitutes a royal army was not precisely defined. The idea of attacking Ayutthaya by King Mangra likely existed since he ascended the throne in 1763 (B.E. 2306). He had accompanied his father’s army during the 1760 (B.E. 2303) campaign against Ayutthaya. Upon accession, he organized the administration efficiently, enabling multiple campaigns during his reign. His military experience in Thailand helped him identify Ayutthaya’s weaknesses and prepare accordingly to ensure victory in later wars.

King Mangra did not personally lead the army against Ayutthaya due to other obligations. Moreover, when assessing the threats to Burma from Ayutthaya and Manipur, Manipur posed a greater threat due to its cavalry forces, while Ayutthaya’s threat was primarily through its influence over frontier vassal states.

The Burmese royal chronicles (Ho Kaeo manuscript) clearly state that when King Mangra received news from Nemyo Sithu that Ayutthaya was about to fall, he ordered that once Ayutthaya was captured, the city should be utterly destroyed, and the king and royal family sent to Burma.

The Burmese plan to conquer Ayutthaya involved sending armies to surround the city from both south and north. King Mangra believed Ayutthaya was strong because it had not suffered warfare for a long time. Sending only the northern army under Nemyo Sithu would be insufficient, so he also ordered Mang Mahanatha to lead the southern army to attack from the opposite side.

The two Burmese armies had other missions to complete beforehand, but these tasks also supported their primary objective: the conquest of Ayutthaya. Nemyo Sithu’s army marched through the border towns to conscript people into their forces, then proceeded through Chiang Mai via Chiang Tung. Nemyo Sithu was responsible for suppressing rebellions in the Lanna region, which he accomplished swiftly. After the rainy season of 1764 (B.E. 2307), he advanced to subdue the Lan Xang kingdom, completing that mission as well. He then stationed his forces in Lampang during the rainy season of 1765 (B.E. 2308), conscripting troops from the Lanna and Lan Xang regions, including princes from the eastern side of the Salween River, to prepare for the campaign against Ayutthaya.

Nemyo Sithu’s army moved from Lampang in the dry season of 1765 (B.E. 2308). Meanwhile, Mang Mahanara’s forces had to first suppress a rebellion in Tavoy (it was impossible to attack Ayutthaya while leaving Tavoy in rebellion). They stayed there during the rainy season of 1765 (B.E. 2308), conscripting troops from Hanthawaddy, Martaban, Mergui, and Tavoy-Tanintharyi. By the dry season of 1765, they advanced into Thailand, joining Nemyo Sithu’s army as scheduled at Ayutthaya.

It is evident that the two Burmese armies did not move simultaneously, as the distances to Ayutthaya differed greatly. Additionally, the towns they encountered along the way varied significantly. The southern army faced relatively smaller towns, except for Phetchaburi; there were few large cities blocking their path. In contrast, the northern army had to pass through many large cities such as Phitsanulok, Sawankhalok, Phichai, and possibly Kamphaeng Phet. Therefore, the southern army was able to reach near the capital earlier, while the northern army took much longer.

Thai historical records reflect this difference in the Burmese movements. The southern army had more time and spent it looting, seizing resources, and taking captives along towns like Kui, Pranburi, Phetchaburi, Ratchaburi, Kanchanaburi, Nakhon Chai Si, Suphanburi, Thonburi, and Nonthaburi.

A letter from a French priest residing in Ayutthaya at that time reported that the Burmese had invaded Ratchaburi and Kanchanaburi since March 1765 (B.E. 2308), but the Burmese forces did not set camp near the capital until September 14, 1766 (B.E. 2309). During the more than one-year interim, the Burmese established camps at the confluence of two rivers (referred to as Tok Raoem and Dong Rang Nong Khao in the Thai Royal Chronicles) and built warships there to conduct guerrilla-style naval warfare before launching the final attack on Ayutthaya. (The Royal Chronicles, Royal Handwriting Edition, Volume 2, page 263)

The northern Burmese army under Nemyo Sithu presents notable discrepancies between the Thai and Burmese sources concerning their military campaign. According to the Glass Palace Chronicle (the Burmese royal chronicle), the first city to fall was Ban Tak, where fierce combat was waged until its eventual capture, plunder, and the local ruler’s imprisonment. This account clearly contradicts the Thai chronicles, which mention a general named Phaya Tak fighting valiantly during the siege of Ayutthaya. The defeat at Tak compelled the rulers of Rae Haeng and Kamphaeng Phet to submit without resistance, thereby sparing their cities from the devastation inflicted upon Ban Tak.

From Kamphaeng Phet, the Burmese forces divided to assault Sawankhalok, where resistance was met but ultimately overcome, with the ruler taken captive. The campaign proceeded to Sukhothai, where the sovereign capitulated peacefully. This contradicts the Thai annals that relate the ruler’s evacuation of his subjects into the forests and subsequent rejoining with forces from Phitsanulok. The Burmese then advanced to a city variously named “Yazama” or “Razama” in the Burmese chronicle, whose ruler likewise submitted. The identification of this city remains uncertain, though it has been conjectured that it may be confused with Ratchasima, a major urban center well known to the Burmese. The Burmese army then proceeded to besiege Phitsanulok, whose ruler resisted but was defeated and taken prisoner. This contradicts Thai chronicles of both the Ayutthaya and Thonburi periods, which assert that Phitsanulok remained free and its ruler later aspired for autonomy. The Burmese encamped at Phitsanulok for ten days before dispatching detachments to subdue the surrounding northern cities—Lalin, Peksa (Phichai), Thani (Ban Kong Thani, possibly the nascent city of Sukhothai), Biksek (Phichit), Kunwansan (Nakhon Sawan), and Inthong (Ang Thong)—none of which reportedly resisted. From these towns, Burmese conscripts were levied to reinforce the army destined for the siege of Ayutthaya.

Thus, the two Burmese armies established a protracted campaign by encamping at Lampang and Tavoy during the rainy season, allowing ample time to prepare for the conquest of the capital. The overarching strategy sought to sever Ayutthaya’s ties with its vassal states—its greatest strategic vulnerability.

The common tactic in the Burmese campaign was straightforward: rebellious cities faced sacking and deportation of their inhabitants as punishment, while those that submitted peacefully were obliged only to supply conscripts and provisions. Additionally, the Burmese dispersed forces to pacify the general populace of the central-western basin of the Chao Phraya River. There is evidence of Thai individuals collaborating with the Burmese, including reports of entire regiments composed of such recruits. A French missionary residing in Ayutthaya in 1765 (B.E. 2308) recorded rumors that many Thais, wearied by hardship, had defected and joined the Burmese ranks. Thus, although initially limited in size, the Burmese army was able to mount a successful siege due to the collapse of Ayutthaya’s system of vassal governance and manpower mobilization.

By late 1765 (B.E. 2308), the Burmese armies united near Pak Nam Prasop, within two kilometers of Ayutthaya, while consolidating control over the outlying towns. The siege was initially lax, allowing refugees to enter the city and food supplies to remain adequate, with only the indigent suffering from hunger. A French missionary chronicled that when the Burmese tightened the siege on September 14, 1766 (B.E. 2309), supplies were still sufficient for the city’s populace.

From September 1766 to the fall of Ayutthaya on April 7, 1767 (B.E. 2310), the kingdom’s collapse was already inevitable. External forces had severed the kingdom’s tenuous bonds to its vassals. Ayutthaya’s defense was fragmented and ineffective, marked by local resistance rather than a united front. This disintegration was rooted in systemic failure—both political and military—to withstand external aggression.

For nearly two years, the capital was isolated from its dependencies, lacking central authority to coordinate defense. The Burmese victory was thus a culmination of the kingdom’s destruction, with the city’s capture a mere consequence of the preceding political and military collapse.

(Vina Rojanratha, 1997: 132–137)