King Taksin The Graet

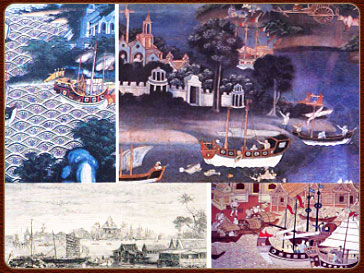

Chapter 15: King Taksin’s Royal Duties in Diplomatic Relations and Trade with China

15.1 What was foreign relations like during the Thonburi period?

During the Thonburi period, foreign relations took two main forms: contact due to warfare and contact due to trade, with the countries involved including:

1. Relations with Burma

Throughout the Thonburi period, Siam and Burma were in constant conflict, engaging in warfare nearly ten times. Notable encounters include the battle with the Burmese at Bang Kung, Samut Songkhram in 1767 (B.E. 2310), the Burmese attack on Sawankhalok in 1770 (B.E. 2313), Siam’s first campaign against Chiang Mai in 1771 (B.E. 2314), and the Burmese assaults on Phichai in 1772 and 1773 (B.E. 2315, 2316). Siam launched its second campaign to retake Chiang Mai in 1774 (B.E. 2317), followed by further engagements in Bang Kaeo, Ratchaburi in 1775 (B.E. 2318), the invasion of the northern towns by General Azaewunky (Alaungpaya) in the same year, and a final Burmese attack on Chiang Mai in 1776 (B.E. 2319).

2. Relations with Cambodia

Cambodia had been a vassal state of Siam since the Ayutthaya period. However, following the fall of Ayutthaya to Burma in 1767, Cambodia regained independence. During the Thonburi period, internal strife split Cambodia into two factions—one loyal to Siam, and the other aligning with Vietnam. This division prompted Siam to send military expeditions to subdue Cambodian resistance on multiple occasions.

3. Relations with Lanna (Northern Thailand)

King Taksin the Great recognized that Burma frequently used Lanna as a strategic base and supply depot during its invasions of Siam. Consequently, he launched a campaign to capture Chiang Mai, succeeding in driving the Burmese out in 1774 (B.E. 2317). From then on, Lanna remained free from Burmese control, with military support from Thonburi ensuring its protection.

4. Relations with the Malay States

The Malay principalities—including Pattani, Kedah (Saiburi), Kelantan, and Terengganu—had long been vassals of Siam during the Ayutthaya era. After the fall of Ayutthaya, these states declared independence. In the early Thonburi period, Pattani and Kedah remained nominally loyal to Siam, but by the latter years, they distanced themselves. King Taksin the Great refrained from launching a southern campaign, as the kingdom lacked sufficient resources to exert control over these distant territories.

5. Relations with China

During the Thonburi period, Chinese junks frequently arrived in Siam to engage in trade. The Chinese merchants brought goods such as weapons—acquired from Western nations—as well as rice and other essential commodities. King Taksin the Great took a keen personal interest in fostering relations with China. He commissioned royal junks to engage in overseas trade with the Chinese and dispatched diplomatic envoys to establish official relations on two separate occasions.

6. Relations with Western Nations

While the Thonburi Kingdom did maintain contact with various Western powers, such relations were not as robust as those during the Ayutthaya era, largely due to the brief duration of the Thonburi period. Among the Western nations that made contact with Siam during this time were the Dutch, English, French, and Portuguese. However, no formal or enduring alliances were established.

(See also detailed accounts of interactions with Burma, Cambodia, Lanna, and the Malay States in Chapter 10.)

15.2 What were Thai–Chinese relations like in the past?

The connection between the Thai people in the Southeast Asian peninsula and those of Chinese ancestry is one that dates back centuries—at least to the Sukhothai period, if not earlier. Historical evidence confirms a long-standing relationship, rooted in maritime trade. The Chinese from the mainland possessed great expertise in navigating junks (large sailing ships), seeking commercial opportunities in regions rich in natural resources throughout the Pacific Rim. This included the Gulf of Siam, after they had already engaged in trade along the coastal areas of the Malay Peninsula.

Research by William G. Skinner, particularly in his work titled Les Songques des Chinois du Siam, suggests that the earliest Chinese arrivals in the Thai realm likely occurred during the early Sukhothai era. These traders sailed junks annually during the northeast monsoon season, following the coastlines of the Malay Peninsula—beginning at its southernmost point, then continuing along the eastern shores near what are now the provinces of Nakhon Si Thammarat, Surat Thani, and as far as Chumphon.

With the arrival of the southwest monsoon season, these Chinese merchants would return to their homeland, bearing goods they had acquired locally in Siam. These goods included forest products, teakwood, silk, textiles, and glazed ceramics

King Ramkhamhaeng the Great

(Image from 203.144.136.10/…/ nation/pastevent/past_ayu.htm)

Regardless of whether it was before or after, such records clearly demonstrate the long-standing origins of the relationship between these two nations and peoples. The formal relationship appears to have taken on a more defined character during the reign of King Ramkhamhaeng the Great, when diplomatic missions from China were sent to Siam multiple times between circa 1282 and 1293 CE (B.E. 1825–1836). Eventually, in 1296 CE (B.E. 1839), King Ramkhamhaeng responded by dispatching an official embassy to China to reciprocate the goodwill. This marked the first formal diplomatic relations between the two kingdoms in recorded history.

During the Ayutthaya period, Thai–Chinese relations appeared to lapse for a period due to internal turmoil in China, which was facing civil conflict and a dynastic transition to the Ming Dynasty. Diplomatic contact resumed when the new dynasty solidified its rule, and commercial relations between the two nations expanded significantly during the reign of King Songtham, around 1620–1632 CE. Chinese merchants from the mainland received strong support and patronage from Thai nobles and high-ranking officials, fostering robust trade relations. (Siam Araya, 1(7): March 1993: 43)

During the 270-year span of the Ming Dynasty, China dispatched official envoys to the Kingdom of Ayutthaya a total of 19 times. In return, Ayutthaya sent tributary missions to the Chinese emperor every three years, amounting to 110 missions in total. Furthermore, the personal goods that accompanied the tribute envoys were exempted from customs duties by the Ming government, reflecting a policy of leniency and goodwill. (Pimprapai Phisankul, 1998: 50)

During the Thonburi period, in the 46th year of the Qianlong reign (corresponding to the third month of the year 1143 in the Chula Sakarat calendar), Xianluoguo Jiang Taijiao (the Chinese name given to the ruler of Siam, though China had not officially recognized him as king) appointed Long Bichanli (known in Siam as Luang Phichai Thani or Phetpranee) and Hegebutad (two vice envoys) as royal ambassadors to present tribute. They reported that since the time when the Burmese rebels had ravaged the land, vengeance was taken and territories recovered, yet the royal lineage of the ruler was extinguished. The nobles collectively elevated Taijiao to power and thus sent local products as tribute according to custom. The senior officials informed the Qianlong Emperor that they were aware Xianluoguo had dispatched envoys across great distances, demonstrating respect and reverence. The senior officials then replied to the ambassador’s message in kind. The Qianlong Emperor, understanding that the envoys had to traverse high mountains and vast seas, granted them a two-day banquet.

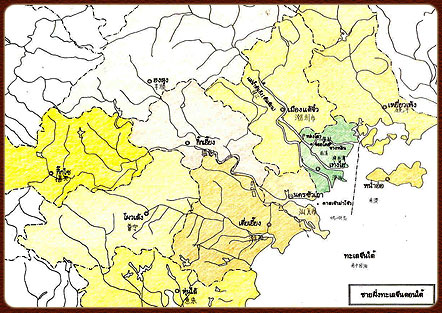

The journey from Xianluoguo passed through the cities of Guangdong and Guangzhou (Beijing). The state of Xianluoguo lies to the northwest, sailing forty-five days and nights on the sea to arrive at the river mouth in Guangdong province. Then setting course southward, they traveled ten days and nights to the Annam Sea (Vietnamese coast), passing a mountain named Wu Luo, continuing eight days and nights to the Great Kunlun mountain. They then changed course northeast for five days and nights to the mouth of the Xiangjiang River, and five more days to the river mouth at Xianluogang. They proceeded upriver two hundred li to freshwater, then five days to Xianluosi (the city).

Xianluoguo has a great mountain to the southwest. The waters flow south from the mountain into the sea. The city’s territory includes Songkhla, Chaiya, Nakhon Si Thammarat, and Tani (Patani).

According to the official who compiled the document Bunxian Tongkao, Xianluoguo’s history traces back to the Sui and Tang dynasties, then called Xietouwu Kingdom. During the reign of Emperor Sui Yangdi in the year 1148 Buddhist Era, the noble Sun Chang Zhusi was renowned in Xietouwu Kingdom. It is noted that the rulers of Xietouwu were adherents of Buddhism, likely sharing the same clan name as Buddhist communities.

On review, it is observed that the people of Xianluoguo do not share a common clan name, and this has been so for over a thousand years. However, the people are of Hulao descent (originally Thai). According to the Lam Shu text about countries south of the sea, Hulao had a female ruler named Siu Ya. The Meng Wang Gai Siktong Kao text praises the women of Xianluoguo as wiser than men, possibly a cultural tradition inherited from Hulao.

Xianluoguo maintained friendly relations with Donghua (China) from the Song and Ming dynasties onward. During the Qing dynasty’s reign, its influence expanded and the emperor ordered royal envoys to bring rice for sale as charity to the people of the realm. When Qing officials traveled to collect special items from coastal countries, they found little benefit in them, comparing them as unlike as heaven and earth.

The ruler of Xianluoguo governed a prosperous and honest kingdom, situated among many countries to the south and southeast, bordering Annam (Vietnam).

(Department of Fine Arts, 1990: 43-45, 69-70)

After Ayutthaya was defeated by the Burmese, Zheng Zhao (King Taksin the Great) gathered the remaining people and launched a counterattack that drove the Burmese back. He then endeavored to restore the nation, and the people urged him to ascend the throne as king. Zheng Zhao prepared to establish diplomatic relations with China and sought royal permission from the Chinese emperor to send tribute. If the Chinese emperor accepted, it would strengthen Zheng Zhao’s political status as a king recognized by neighboring countries. Therefore, Zheng Zhao sent envoys to China to request permission to send tribute.

The relationship between King Taksin the Great and the Qing dynasty can be divided into three phases according to time and the development of events:

Between 1767 and 1770 (B.E. 2310–2313), the Qing dynasty refused to recognize the Thonburi regime because at that time China was largely influenced by distorted reports from Moselin of Phutthaimat, and therefore did not acknowledge Thonburi. Additionally, during the first three years of King Taksin’s reign, China was engaged in warfare with Burma.

Emperor Qianlong (Qianlong Emperor, 1736–1799)

(Image from www.chinapage.org/ dragon1.html )

1770–1771 (B.E. 2313–2314)

The Qing court began to realize the distorted reports given by Mo Shulin and started to distrust them. Therefore, the Qing court gradually changed its attitude to become friendly toward King Taksin.1771–1782 (B.E. 2314–2325)

The Qing court officially recognized King Taksin and provided special support (Foundation for the Conservation of the Old Palace, 2000: 93-94). King Taksin began to apply the concept of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” to open channels of communication with the Qing court. Whenever he captured enemies hostile to the Chinese government or obtained Chinese soldiers who were prisoners of war under the Burmese during battles, the King of Thonburi would send them back to Guangdong as a gesture of goodwill and to prove sincerity in building relations with China. The Qing dynasty chronicles record that the return of Chinese people happened four times, including:

In 1772 (B.E. 2315), Jiang Junqing and his group were sent back to their homeland.

In 1775 (B.E. 2318), 19 Yunnan soldiers who were prisoners of war under the Burmese were sent back.

In 1776 (B.E. 2319), 3 Yunnanese merchants were sent back to their homeland.

In 1777 (B.E. 2320), Ai Ke and 6 others, who were Burmese captives, were escorted back to Guangdong.

Thus, the atmosphere of friendship with the Qing court gradually developed (Pimprapai Pisankul, 1998: 189).

a. How many times did King Taksin send envoys to China?

There is an article by Professor Chu Wenjiao who studied the relationship between Burma and China. He stated that Chen Zuo (King Taksin) sent envoys to China twice: the first time in the 36th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, and the second time in the 46th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, corresponding to the years 1771 and 1781, respectively.

Professor Chen Jinghe wrote an article titled Several Problems Regarding the King of Thai, also concerning Chen Zuo. In this article, it is said that between the 33rd and 46th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, Chen Zuo sent envoys to China a total of eight times.

In 1768 (B.E. 2311), the 1st envoy was sent during the 33rd year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign. The envoy was Chen Mei.

In 1771 (B.E. 2314), the 2nd envoy was sent during the 36th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign. This was also the period when Siam sent Burmese prisoners to China.

In 1772 (B.E. 2315), the 3rd envoy was sent during the 37th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign. Siam sent Chinese people from Haiphong, including a person named Chen Junxing, to China.

In 1774 (B.E. 2317), the 4th envoy was sent during the 39th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign. This mission was to request the purchase of iron and sulfur.

In 1775 (B.E. 2318), the 5th envoy was sent during the 40th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign. Siam asked a Chinese merchant named Chen Wanshen to deliver a royal letter to China.

In 1776 (B.E. 2319), the 6th envoy was sent during the 41st year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign. Siam requested a merchant named Mo Guangyi to deliver a royal letter to the Chinese emperor.

In 1777 (B.E. 2320), the 7th envoy was sent during the 42nd year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign. Chen Zuo sent envoys along with Burmese prisoners to Guangdong.

In 1781 (B.E. 2324), the 8th envoy was sent during the 46th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign. Chen Zuo sent envoys to the court of the Chinese emperor (sent twice in this year).

Natthaphat Chantrawich (1980: 49-72) discussed the relationship between Thailand and China during the late Ayutthaya period in the article titled “Some Facts about the History of Late Ayutthaya and Thonburi from Chinese Chronicles,” stating:

“In the Chinese perspective, the relationship between China and Siam was similar to that which China had with Korea and Vietnam. Furthermore, China and Siam were believed to share the same origin, with Siam considered a branch of China.”

The history of Siam as known to China records that Xianluowu (เสียนหลอกวั๋ว) was originally divided into two kingdoms: “Luosuo” (Lo-Tsho, or the Kingdom of Lopburi) and “Xuan” (Hsuan, or the Kingdom of Sukhothai). Luosuo flourished under the influence of the Khmer Empire. During the Song dynasty, in the 2nd year of Emperor Cheng-Ho’s reign (1657 BE), Luosuo began diplomatic relations with China. Meanwhile, Xuan engaged in warfare with Luosuo and began establishing relations with China during the Song dynasty, in the 5th year of Emperor Pao Yao’s reign (1800 BE).

Towards the end of the Yuan dynasty, China sent envoys to the Kingdom of Xuan three times, while Xuan sent envoys to China nine times, and Luosuo sent envoys five times. In the 10th year of Emperor Chih Chen’s reign (1893 BE), King U Thong established the Kingdom of Ayutthaya and crowned himself the first King Ramathibodi.

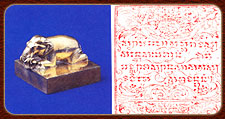

During the 10th year of Emperor Hung-Wu of the Ming dynasty (1920 BE), the king of Luosuo, known as “Chandia Paya” (King Borommatrailokkanat or Khun Luang Phuang), waged war against the Kingdom of Xuan and was victorious. In September 1920 BE, this king sent his prince to China to present elephants, timber, and gold to Emperor Ming Tai-su (who reigned from 1911–1942 BE). Emperor Ming Tai-su granted a seal inscribed with the title “Xianluowu Wangsi Yin” (เสียนหลอกวั๋วหวังซื่ออิ้น) to the prince before his return. From that time onwards, China referred to Siam as “Xuanluo” (Hsuan-Lo), pronounced “Siam-lo” in Teochew dialect.

During the Ming dynasty, Siam and China maintained good diplomatic relations with frequent exchanges of envoys. Envoys from Xuanluo were sent to China a total of 97 times. All Ming emperors continued the tradition established by their first monarch.

In the Qing dynasty, Xuanluo continued to send tribute to China. In the 9th year of Emperor Shunzhi’s reign (2195 BE, December), King Prasat Thong sent envoys bearing tribute to the Chinese emperor and requested a royal seal. The Chinese emperor granted a golden-gilded silver seal topped with a carved camel figure. The seal bore the inscription “Xuanluowu Wang,” meaning “King of the country Xuanluo.”

Later, in the 17th year of Emperor Yongzheng’s reign (2272 BE), a Chinese seal inscribed with the phrase “Tian Nan Luo Guo” was bestowed. This seal means “Heavenly realm of the southern land.”

In the 14th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign (2292 BE), a framed paper bearing the inscription “Yan Fu Ping Fen” was granted. The relationship between Siam (or Xuanluo) and China, which began during the Song dynasty, continued into the Qing dynasty. In the 32nd year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign (2310 BE), Burma attacked and captured Siam (Ayutthaya), causing a disruption in relations. When King Taksin, called “Zhenjia,” reunified the country, he sent envoys to China to reestablish diplomatic ties.

The diplomatic relations between Siam and China during the late Ayutthaya period and the Thonburi period, as recorded in Chinese annals, provide fascinating historical insights into that era.

In May 2301 BE, the 23rd year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, King Borommakot (known in Chinese as “Wang Polong Moge”) passed away, triggering a succession dispute. According to testimonies from a Siamese man named Chen Mo and a merchant named Wun Xiao, King Borommakot (also called King Dharma Raja) had two primary queens. One bore a son named “Xiao Gong” (likely Prince Sena Phithak, born to Krom Luang Aphaiyuchit, originally Prince Thamthibet), while the other queen bore two sons, “Xiao Hua Yiji Xie” and “Xiao Hua Liu Lu” (likely Krom Khun Anurakmontri and Krom Khun Phonphinit, born to Krom Luang Phiphitmontri, i.e., Princes Ek That and Utumphon).

Xiao Gong reportedly behaved poorly, so King Borommakot assigned another son (by a consort) to eliminate him. However, Xiao Gong had two sons: “Xiao Ya Le” and “Xiao Si Chang” (the princes Keng and Chuen). After King Borommakot’s death, some officials vied for the throne. The eldest son of the second queen, Xiao Hua Yiji Xie, was the likely heir but was weak in health, so his younger brother Xiao Hua Liu Lu ascended instead. This caused discontent from the elder brother, who tried to reclaim the throne.

Xiao Hua Liu Lu abdicated the throne in favor of his elder brother and ordained as a monk residing at Wat Pradu. The people called him “He Sang Wang,” which in Thai was Khun Luang Ha Wat. The elder brother who ascended the throne was commonly called “Mafong Wang,” meaning Khun Luang Kee Ruad (the leprous lord). Other princes born from concubines were dissatisfied and attempted to send messages to King U-Tufan (Burma) in the year 2301 BE (the 23rd year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign). At that time, the Burmese king of the Alaungpaya dynasty was named Aungzeya, who had conquered the kingdom of Manipur (called “Bai Guo” by the Chinese). The Tai Lin people (Talaeng or Mon) fled from Burma into Ayutthaya’s territory. Burma also seized the city of Negrais. The Talaeng sought revenge against Burma, prompting the Burmese king to attempt to purge the Talaeng, which eventually led to an invasion of Siam.

However, Xiao Hua Liu Lu was aware of these plots and thus eliminated the dissenting younger princes. Another cause of discontent among the princes was that Mafong Wang’s brother-in-law, Phaya Nanai (Phraya Ratchamontri Borirak, also known as Pin, the elder brother of the chief consort), was the sole advisor whose counsel Mafong Wang followed. This led to resentment toward Phaya Nanai. Knowing this, Phaya Nanai reported to Mafong Wang and was subsequently sent to “Liu Long Ja” (a place not recorded in Thai chronicles) west of Ayutthaya.

Additionally, Chen Mo testified that Xiao Wang Ji, a younger brother of Mafong Wang, was then 50 years old, and that one of King Borommakot’s queens was of the Bai Tou Fan ethnicity (likely Mon).

Chinese records further note that in November 2303 BE, the 25th year of Emperor Qianlong, Phaya Nanai attempted to build relations with Burma, which launched two invasions of the Thai border area. In that year, King Ekathat (Khun Luang Kee Ruad) fell ill. Phaya Nanai tried to encourage Burma to wage war, but Khun Luang Ha Wat learned of this, and Phaya Nanai was killed before the war began. The Burmese king “Mang Nong” (King Mangrai or Alaungpaya) led the invasion but died of smallpox on the way at Satem. Consequently, the Burmese army retreated.

After King Mang Nong’s death, King Manglok (Son Naungdaw-Gyi), called “Mang Ji Jue” or sometimes “Mang Lua” or “Mang Nao” by the Chinese, succeeded him. He moved the capital from Mu Su (Ratanasingh, originally called Mukchopo village) to Si Jao or Takong or Sagaing. The people thus called him “Sagaing Min” (King of Sagaing).

During the reign of Emperor Qianlong, in April 2305 BE (1762 CE), Xiao Wei (believed to be the Chinese name for Krom Muen Theppipit) was sent away from the city of Tavoy (Dawei) to another place called “Tan Liao” (according to Thai chronicles, he was exiled to Lanka, but Tan Liao likely refers to Tanintharyi, which the Chinese sometimes called Tan La).

In 2306 BE (1763 CE), the Burmese king passed away, and his younger brother Mangra (Mydu) ascended the throne with the royal name King Hsinbyushin, meaning “White Elephant King.” When he was born, ants were found at his cradle, hence the nickname “Mang Pwo.” This king was said to be the smartest among his three brothers (though Thai chronicles mention seven siblings). He was also a skilled warrior who accompanied his father in many battles, making his reign notable. King Hsinbyushin moved the capital back to Mu Su (formerly Ratnasing) and then later to Ava (Inwa).

In 2307 BE (1764 CE), the 29th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, the Burmese king sent his younger brother to lead an army against Siam and dispatched his son, Mang San, to attack the city of Hongsawadi. In this year, the Burmese sent 3,000 soldiers by boat and colluded with some Thai people within the kingdom to gather intelligence. The region from Tavoy to Tan Lo (Tanintharyi) fell entirely under Burmese influence.

Two Chinese individuals named Chai Kaichun and Yang Ya Wu reported that the Burmese army attacked the city of “Tao Hai” (likely Tavoy). By winter, the city fell. In January 2308 BE (1765 CE), Xiao Wang fled to the city of “Luo Yong” (likely a distorted form of “Xiao Wei,” referring to Krom Muen Theppipit, who fled from Tanintharyi to “Huang Yong,” i.e., Phetchaburi).

However, the border city of Tan La (Tanintharyi) resisted Burmese occupation. The people fought back and eventually evacuated, leaving the city deserted. The Burmese then took control of Tao Hai and also captured the city of Wang Ke without opposition on July 13, 2308 BE (1765 CE), during the 30th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign. At that time, the Thai commander named Phao Ya Phali (Phraya Rattanathibet from Nakhon Ratchasima province) fled the city, while the deputy commander Wang Wei Li (unknown in Thai chronicles) was killed.

In January 2309 BE (1766 CE), Sa Wang Ji traveled to the city “Wan Bu Pa Liu Wang Kong” (unidentifiable), and Xiao Wang, knowing the Burmese were pursuing him, went to establish a settlement at “Gao Lie Fu Yi Tou Mu Su An Li Wang” (unidentifiable). Later in the spring, the Burmese army seized the capital city. The Thai army could not keep up with them, but a group of Thai soldiers established a camp under the leadership of Yao Hua Bao (likely Phraya Kamphaeng Phet, later King Taksin).

Another report states that the Burmese army captured the capital city and seized 47 Thai military camps, so the entire country was filled with Burmese soldiers. Most officials stayed with their families and avoided fighting, except for some Chinese who resisted the Burmese. During this time, the country suffered from poverty due to war and disease, with about 100 people dying daily from starvation.

By January 2310 BE (1767 CE), the 32nd year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, the Chinese community joined forces to build a wall to resist the Burmese. In February, the Burmese tried to destroy the wall, breaking part of it, which led to fighting lasting seven days and seven nights. About 3,000 Burmese soldiers were killed. However, the city ran out of food and water, making it impossible to continue the defense. On February 21, the wall was destroyed.

In March, the Thai king, Somdet Phra Chao Ekathat (known as Mafong Wang), was captured by the Burmese. He offered to pay tribute, but the Burmese general Thihapate refused and took him prisoner. On May 9, the Thai capital was destroyed. Somdet Phra Chao Ekathat fled secretly to the city of Pho San Thuan (possibly Pho Sam Ton, though this detail differs from Thai chronicles) but was eventually executed.

The king’s younger brother, Krom Luang Ha Wat, along with officials and palace women, were taken captive by the Burmese, who also looted all valuables from the royal treasury. On May 25, the Burmese army retreated but left the general Sungi (Suki or Chuk Kyi) in charge of the city. Thus, the Thai kingdom known to the Chinese as “Da Chen” came to an end due to Burmese destruction. This kingdom had flourished for 417 years and had 33 reigns.

Afterwards, a new Thai king emerged, “Zhen Zhu” (King Taksin the Great). He established a new dynasty called “Tong-udee” (Thonburi). Upon his coronation, he was titled Somdet Phra Borom Ratcha Thi 4, but China referred to him as “Zhen Zhu,” meaning King of Zhen.

Thai chronicles say that Zhen Zhu’s original name was Shin or Sin, but a Thai named Mai En Sen and a merchant named Chen Ying called him Phraya Tak. Phraya Tak’s father was a Cantonese man from Shen Yong city. Upon arriving in Thailand, he married a Thai woman, and their son was Zhen Zhu, whose original name was Shen Xin. The name Shin (Sin) in Thai means “treasure,” so the Chinese rendered it as “Zhen Cai” (Cai meaning treasure). “Zhen Zhu” was the formal name used when sending tribute to China during the Qing dynasty and in official contacts with China.

A Chinese book titled “Si Shi Er Meng Zhu Xi” records that Zhen Zhu’s father was named Shen Yong or Shen Yong, who came from Chaozhou near “Chen Hai Wa Hu Li” or “Deng Hai Fa Fu Li.” Because Shen Yong’s father was wealthy, Zhen Zhu himself was not very interested in work, spent money freely, and liked traveling. Villagers thus called him “Tai Si Ta,” meaning traveler.

Therefore, due to this bad character, he became poorer over time and began traveling southward. At that time, there was a lot of trade between Thailand and China. He gambled and luckily became wealthy, so he changed his name to “Yong” and traveled to Thailand. He married a Thai woman named “Luay Yong,” or Lady Nokk Yang, and their first child was Zhen Zhu, born in 2277 BE (1734 CE), the 12th year of Emperor Yongzheng’s reign.

Luang Vijitwathakan also wrote about Zhen Zhu’s history, stating that when King Taksin was born, his father found a snake in the cradle and, believing it to be a bad omen according to Chinese beliefs, tried to abandon the child. However, a Thai noble named Chao Phraya Chakri thought the child was handsome and took him in as his son. At age 9, Zhen Zhu studied with a monk named Thong Dee (some sources say with teacher Suk at Wat Phraya Muang in Wiset Chai Chan district). At 13, he entered the royal court as a page, and at 21, he left to become a monk for three years. After ordination, he entered royal service as Tai Sao (city governor) of Tak. Later, he was promoted to Phraya Wachiraprakarn. The Thai people greatly admired him and called him Phraya Tak, Phraya Sin, Phraya Taksin, or Chaophraya Taksin. However, in Qing dynasty Chinese records, he was first called “Gan Yin Le” but later known as “Zhen Zhu.”

In February 2310 BE (1767 CE), the 32nd year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, because the Burmese had been attacking the Thai capital for three years and the Thai king was poor at warfare, Zhen Zhu was assigned to help defend the capital along with another official named Po E Biu Wu Di (Phraya Phetchaburi). Both were skilled in defending the city. Zhen Zhu was tasked with protecting Wat Phichai in the capital. However, some nobles forbade the firing of guns for fear it would alarm the king and palace women, causing Zhen Zhu to become disliked. Once, when the Burmese breached the wall, Zhen Zhu had no time to report to the king and ordered the firing of guns, angering the king. Zhen Zhu then no longer wished to defend the capital.

According to Ah Yu Tua’s testimony, when the Burmese army breached the city wall, the Thai army retreated inside and closed the city gates, but only Zhen Zhu led his soldiers to fight the Burmese, breaking through toward Wat Phichai with about 500 men following him.

In May of the same year, Zhen Zhu captured Chanthaburi. According to British chronicler W.A.R. Wood, the governor of Chanthaburi was an ally of Zhen Zhu. Upon hearing that the capital had fallen to the Burmese, the governor hoped to become king himself and tried to lure Zhen Zhu to Chanthaburi to raise an army to retake the capital. But Zhen Zhu saw through this and captured Chanthaburi by surprise at night while the Burmese still held the capital.

At this time, Thailand was fragmented into many factions, with groups fighting each other to gain power.

“Mung Mo Su Lin,” a resident of He Xian city, reported that “Pe Sai Chin” (Phraya Sin) captured the city of Wang Ge (understood to be Thonburi) and that others governed various cities. However, “Sa Wang Ji” (Krom Muen Theppipit), a younger brother of the king, held great power and was widely respected. Sa Wang Ji led an army back to seize the city of Gao Liao (Phimai) and tried to gather scattered troops as well as establish a new capital.

Another figure, “Sa Chu Chang” (Chao Sri Sang, son of Krom Phra Ratchawang Bowon Sathan Mongkhon), a half-brother, fled from Thailand to live in Cambodia. There was also “Sao Tre” (identity unknown), whose descendants fled to He Qian city (likely Sawangaburi), where at that time many Thais—men and women—gathered, numbering over thirty thousand.

Sao Tre reported to the Chinese emperor that he was troubled by the destruction of the capital by the Burmese and the death and dispersal of the royal heirs. Some were captured by the Burmese. His uncle, Sa Wang Ji, resided in Gao Liao, while he himself had fled to He Qian. His younger brother “Si Chan” (Chao Chui, son of Krom Phra Ratchawang Bowon Sathan Mongkhon) lived in Cambodia. The Khmer king showed kindness and granted all requests, seeing Thailand as the origin of the “Heavenly City.” Furthermore, Sao Tre’s sister had shown kindness to the people of He Qian.

Additionally, a noble named Phraya Sin or Zhen Zhu attempted to declare himself king, refusing to acknowledge the Thai royal family and even enslaving them. Zhen Zhu gathered forces to attack Gao Liao where Sa Wang Ji stayed. Sa Wang Ji fled near the border of the city “Lao Gua” (Ayutthaya). The governor of Lao Gua sent Sa Wang Ji back, but on the way to Wang Ge, he was executed by Zhen Zhu.

Zhen Zhu then led his army to He Qian, but the Khmer king did not allow him to do so. The Khmer king promised Sao Tre and Sa Chu Chang that he would help them reclaim the capital. At that time, Sa Chu Chang was 24 years old, and Sao Tre was 39. Sao Tre could not restore the country by himself due to lack of power, while Zhen Zhu was trying to claim the throne unofficially.

According to Zhen Zhu’s report, the former Thai king resided in the southern part of the palace and had long sent tribute to the Chinese emperor. When he died, “Se Hua” (King Ekathat) ascended the throne. However, “Sao Wang Ji” (likely a corruption of Sa Wang Ji), a royal relative, attempted to eliminate him but failed. He then conspired with “Wa Tu” (another Chinese name for the Burmese) to besiege Thailand until the capital was captured. The king was executed, palace goods were stolen, and the royal palace was burned down.

At that time, Sao Awangji seized control of the entire palace. However, Sao Awangji, Sao Tre, and Sao Tang feared that the people would rebel, so they refused to return to Thailand. As a result, the country had no ruler. They attempted to take revenge but were unable to establish a stable nation. The border regions were unsettled, and neighboring countries tried to take advantage of the power vacuum. Because the country was in the midst of war, the king and royal relatives resided abroad and refused to return to rebuild the nation. The people therefore chose one of their own to become king.

In the early period when Zhen Zhu captured Chan Jue Aun (Chanthaburi), the city’s lord named Wang Qian (the governor of Chanthaburi) surrendered to Zhen Zhu and even gave his daughter to him. Later, when Zhen Zhu took Trat, officials and soldiers from various places joined him, numbering about five thousand. They built a fleet of one hundred ships and sailed up the Meilan River (Chao Phraya River).

In August of the 30th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, Zhen Zhu returned to Wang Ge and killed Thong In, the puppet king installed by the Burmese, taking control of the Burmese camp. He also killed Sung Yi (Suki), whom the Burmese had appointed as overseer. At that time, Zhen Zhu’s troops had grown to tens of thousands. Zhen Zhu became a prominent figure not only by reclaiming the country but also by inviting royal relatives back and bringing the remains of former kings to perform royal ceremonies according to tradition.

Thus, in January of the 33rd year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, 1768 CE, the Thai people decided to choose Zhen Zhu as their king.

Another record states that during the period of Burmese occupation, the former king died, the people were impoverished, and the land was rife with criminals. Chaophraya Tak, known in the Chinese record as “Jao Phaya Kan En Le,” gathered people to fight against U Tu Fan (the Burmese). He restored order to the country. Chaophraya Kan En Le unified the kingdom and established the capital at Mangu (Bangkok). To sustain the people, he encouraged the collection and trade of forest goods and food supplies.

The various warlords became wary of Zhen Zhu because he was a capable leader. At that time, the country could not find a rightful heir to the throne, so the people pleaded with Zhen Zhu to become king. He resided in Bangkok, but conditions there were poor; buildings were in ruins and difficult to repair or rebuild. Therefore, he decided to establish a new capital to the south at Thonburi, marking the beginning of the Thonburi dynasty.

Zhen Zhu was then 34 years old. It is said that one reason for founding the new city was a dream in which former kings appeared and drove him away from the old capital. He took this as a bad omen and decided to move to Thonburi. Another reason was that Ayutthaya was too damaged to restore, whereas Thonburi was strategically located, easier to defend, and close to the sea, making it suitable as a trading port.

The reason Zhen Zhu did not succeed in sending tribute to the Chinese emperor on his first attempt.

In the year 1765 (B.E. 2308), relations between China and Burma began to deteriorate significantly due to border disputes. Later, in 1767 (B.E. 2310), the 32nd year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, amid escalating border troubles, the governor of Yunnan Province, named Yang Yingzhu, submitted a petition to the Chinese emperor. He requested that the emperor dispatch fifty thousand troops to fight the Burmese on five different fronts. He also advised the emperor to seek an alliance with the Siamese (Thai) to jointly resist the Burmese.

However, Emperor Gaozong (Qianlong) found Yang Yingzhu’s suggestion somewhat absurd. He believed that mobilizing such a massive military force and relying on foreign nations to help fight one’s own enemy was neither wise nor appropriate. The emperor refused to follow this advice, citing the example from the Ming dynasty, when they had weak power and sought help from other nations. In contrast, under the Qing dynasty, China had a full and strong military both domestically and abroad, and many countries sent tribute to support China’s war efforts against Burma. At that time, Emperor Gaozong was unaware that Siam was being attacked and that the Burmese had already captured its capital.

Nevertheless, the Qing dynasty decided to commence warfare against Burma in the winter of that year but did not seek military assistance from other countries. Because Siam shared a border with Burma, and to prevent the Burmese king from fleeing into Siam, China requested Siam’s cooperation to block Burmese escape routes.

At that time, Guangdong and Hainan provinces were international ports with many trading ships docking there. On June 17, 1767 (the 32nd year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign), the emperor ordered the governor of Guangdong-Guangxi, named Si Ya, to send a letter to Siam, urging them to watch for any attempts by the Burmese king to escape into Siam as China engaged the Burmese militarily.

The next day, Siamese officials arranged and sealed a letter concerning this matter to be sent to the governor of Guangdong-Guangxi. Later in September of the same year, a trading ship from Annam (Vietnam) sailing from Guangzhou arrived. Si Ya entrusted this ship to deliver the letter through Chu Chuan, with plans for Chu Chuan to hand it over to officials under Mo Su Lin, the governor of Heqian (Hao Chien), who would then pass it on to Pu Lan, a Siamese official.

On September 9, Chu Chuan, accompanied by an official named Wang Guo Zhen and a ship owner named Yang Jin Zhong, boarded the ship Mo Guang Yi at Fu Men (Tiger Gate). They departed, and by October 10, they reached Annam Bay. However, due to severe weather and strong winds, the ship could not dock and had to wait offshore. On October 12, the storm worsened, causing one of the ship’s masts to break. The next day, the winds intensified further, forcing the ship to leave the bay. On November 3, the ship finally stopped at Lu Kwen, believed to be the city of Nakhon Si Thammarat, often simply called “Lakhon.”

During that time, Chu Chuan fell ill with cholera. His bodyguard, named Mei Shen, reported this to officials in Lu Kwen. On November 5, Chu Chuan was taken off the ship and brought ashore to Wu Di Temple. Officials of Lu Kwen sent a doctor named Nai Su Nai Jian to treat him, while Mei Shen also sent a Chinese doctor to examine Chu Chuan, distrusting the local physicians. Nevertheless, Chu Chuan passed away on November 15. It was later recorded that Wang Guo Zhen also fell ill on January 1, 1768 (B.E. 2311) and died on January 22 of the same year.

On January 2, 1768, the 33rd year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, the emperor ordered officials to send a letter to Si Ya, instructing them to closely monitor developments in Siam. The letter stated that if the Siamese king resolved to reunify the country but lacked sufficient power, and requested Chinese military assistance, China was willing to send troops. However, at the same time, China asked Siam to assist in fighting against Burma.

On August 1, Jen Chao (Zhen Zhao) dispatched an official named Chen Mei to deliver a royal letter to Emperor Qianlong. The letter expressed respectful greetings and obeisance to the Chinese emperor on behalf of the Siamese monarch and people. It affirmed Siam’s loyalty to China, which deterred neighboring states from aggression. However, the letter reported that Burma had invaded Siam three times, destroying the capital. The sender earnestly requested China’s assistance, confident the emperor would not allow Siam to lose sovereignty to Burma.

The letter further explained that the current Siamese king, his two brothers, and other nobles were unable to restore the country. Therefore, they sought help from “Zhan’erwen” (a corrupted form referring to Chanthaburi). Yet upon arrival, it was discovered that Chanthaburi had already fallen, and the people were fleeing due to severe famine.

Historically, Siam had sent tribute to China, and the emperor had graciously responded with gifts that earned respect and fear from neighboring states. But now the country was fragmented and in turmoil; the forests and mountains were filled with bandits; there was no effective ruler controlling the land. The letter described the Siamese efforts to resist Utu Fan (the Burmese) and “Wenzi” (understood to be the Mon), both of whom had sent armies to attack.

Because of the emperor’s blessings, Siam was able to continue fighting the Burmese and even won some victories. However, they had not yet located the king’s brothers to bring them back to restore the monarchy. The letter noted that the cities of “Hu Sulu” (unknown location), “Lu Kwen,” and “Gao Lie” (Pimai) were under the control of Ava (Burma) and refused to submit to Siam.

Therefore, I humbly beseech Your Majesty’s gracious assistance to help restore Siam to its former prosperous state, respected and feared by neighboring countries. The bandits will be eradicated. However, due to our limited funds and food supplies, we have resorted to gathering ivory, fine wood, and birds to trade for money to buy food. Furthermore, we lack sufficient nobles and officials to suppress the smaller independent states. If Siam has a new king, wise and capable, and recognized as the legitimate monarch, then the people and armies will unite to fight and subdue those independent realms.

I have sent a ship laden with tribute to Your Majesty, and I pledge my lifelong loyalty and service. Should Burma send troops again, we will fight them. Should Your Majesty dispatch armies to subdue Burma, I will obey Your royal command. Yet I remain uncertain whether my plea will be effective because I do not know how former kings sent tribute, as the royal decrees and laws were all burned during the war. If Your Majesty would kindly inform me of these regulations, I shall send tribute as was done by the former kings.

In that same year, other independent rulers also sent letters to the Chinese emperor, requesting to be recognized as the rightful king of Ayutthaya, succeeding the deceased monarch during the war. With several independent states existing, Jen Chao (Zhen Zhao) had not yet fully unified the country. Therefore, the Chinese emperor had not recognized Jen Chao as king. If Jen Chao wished to gain acceptance among neighboring countries, he must first request a special royal title from the Chinese emperor. Receiving such a title would grant him a special status in the region. Even though the people sincerely chose Jen Chao as king of Siam and requested his rule, it was not as significant as receiving an official appointment from the Chinese emperor, which would support recognition by neighboring states.

The envoy who delivered Jen Chao’s letter to the Chinese emperor was named Chen Mei. Another letter was presented to the governor of Guangdong-Guangxi provinces, whose name was Li Si Ya. He reported the contents of Jen Chao’s letter to the Chinese emperor and also advised the emperor to send a reply to Jen Chao. Additionally, the governor reprimanded Chen Mei for improper conduct.

On August 19, 1768 (year 33 of the Qianlong reign), the emperor Qianlong agreed to the proposal presented by Li Siyue, the governor of Guangdong-Guangxi. The emperor held the view that Jen Chao (Zhen Zhao) was a commoner and should not act in the manner of the previous kings of Siam.

The letter drafted by the governor of Guangdong-Guangxi to Emperor Qianlong for his consideration before being sent to Jen Chao essentially stated that Jen Chao was an ordinary man who wandered like a pirate, and thus was more suited to be a pirate chief than a king. Although Siam was in peril and Jen Chao had helped, he had no legitimate right to be king. Even though he restored the nation’s independence, it was improper for someone without royal lineage to claim kingship, and such a claim was not accepted.

Li Siyue reprimanded Chen Mei for improper conduct regarding this matter. While Emperor Qianlong agreed with Li Siyue’s position, he also admonished Li Siyue for not treating Chen Mei respectfully and advised him to send a letter explaining the reasons clearly to Jen Chao. The emperor emphasized that China respected law and tradition, and could not accept deviations from established customs. Many others desired recognition as king of Siam, and Jen Chao’s situation resembled a usurper seizing the throne of a previous monarch.

Furthermore, Emperor Qianlong instructed Li Siyue to explain this reasoning to others seeking to be king of Siam, not merely to criticize without explanation. Upon learning this, Li Siyue drafted two letters: one for Chen Mei to deliver to Jen Chao, and another to be sent to Mo Su Lin (Mao Suling), the governor of Hechian. Since Li Siyue felt unable to draft the letters properly himself, he entrusted a nobleman to prepare the drafts, which Li Siyue then reviewed before sending.

The letter stated: “China cannot recognize Jen Chao as king nor grant him a royal seal because it would contravene established traditions. Jen Chao should seek the rightful heir, assist him in restoring the nation, and enthrone him as king. Jen Chao has not done so but instead declared himself king. China disapproves of such improper and immoral conduct. Moreover, three other states continue to resist you, such as Lu Silu. Since you are not the rightful heir, you should respect the original royal lineage. Therefore, you are urged to find the legitimate heir and help him restore the kingdom.”

The letter sent to Mo Su Lin (Mao Suling) stated that Emperor Qianlong did not officially recognize Mo Su Lin, but acknowledged that Sa Thet (Se Ta) fleeing to Hechian and receiving Mo Su Lin’s support was commendable. Mo Su Lin was regarded as someone knowledgeable of customs, traditions, and morality. Therefore, the emperor bestowed a robe as a token of approval for his actions.

From this account, it is evident that Siam appeared to be under Chinese suzerainty for an extended period, as it continuously sent tribute to the Chinese emperor. China respected the Siamese kings and, when Jen Chao (Zhen Zhao) attempted to proclaim himself king, China refused to acknowledge him, knowing that the legitimate heir was still alive. The special seal previously granted by China remained valid, but no new seal was issued to Jen Chao. This marked the first occasion where Jen Chao’s tribute mission to China did not succeed.

The Second Tribute Mission

In September 1768 (year 33 of the Qianlong reign), Sa Wang Ji, the legitimate Siamese heir, traveled from Wangkao back to the capital. However, on October 25, he was executed. At that time, Li Siyue, governor of Guangdong-Guangxi, had already sent a letter to Jen Chao more than two months earlier, but the Chinese emperor had not yet received any reply from Jen Chao.

Meanwhile, China dispatched an official named Chen Ce to fight the Burmese and successfully captured Ava. However, no official report from Siam about its efforts to reunify the country was sent to China. Mo Su Lin, governor of Hechian, sent maps depicting naval routes from Guangdong to Burma and Siam, along with letters describing his future plans, which were presented to Emperor Qianlong.

Following this, Emperor Qianlong instructed Li Siyue to send officials quickly to Hechian to inquire about the situation in Siam and request reports to be sent to China. Li Siyue complied, selecting officials named Jen Re and Chen Thayang to travel on a merchant ship to Hechian.

Another Chinese official sent to fight the Burmese, Ming Re, was killed. In response, Emperor Qianlong sent Fu Ren to command the troops, along with advisors Ali Guan and A Gui. These officials were concerned that Mone Pang, the Burmese king, might flee to another country. Therefore, Emperor Qianlong instructed Fu Ren to contact the ruler of Nansong and request cooperation in the campaign against Burma.

In the year 1769 (B.E. 2312), during the 34th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, the emperor ordered an official to draft a plan for commencing war against Burma. He also sent a letter to Li Siyue, instructing him to officially seal and send the letter to Siam. This letter requested Siam’s assistance in preventing the Burmese king from fleeing through Siamese territory. Additionally, the emperor inquired whether Jen Chao had found the true heir of Siam, whether the descendants of the Sa family were cooperating to reunify the country, and whether Jen Chao was still governing internally. The emperor requested Jen Chao to send reports back to China, as he wished to know who truly ruled Siam at that time.

On June 27, Jen Re and Mo Wenlong, officials sent by Mo Su Lin from Hechian, departed by ship from Hechian to Guangzhou, carrying two letters from Mo Su Lin for the Chinese emperor. One letter reported events in Siam, while the other reported on Burma. Jen Re presented a detailed account of the conflict between Siam and Burma and described the maritime routes between China and Siam.

According to Jen Re’s report, Mo Su Lin, governor of Hechian, had dispatched Chen Lang to lead an army against Jen Chao in December of the previous year. In January, Chen Lang captured the city of Tongzhai. In February, Mo Su Lin sent Chen Ji to reinforce Chen Lang, who then attempted to capture Sansewen (likely Sawankhalok). Chen Lang successfully took Sansewen and captured its ruler, Ling Gongshen, bringing him to Hechian. Chen Qingxiang was also sent with 2,000 soldiers to attack Wangkao, where Jen Chao was based. However, Jen Chao’s forces were strong, and Chen Qingxiang failed to seize Wangkao easily.

Mo Su Lin’s letter also accused Jen Chao of declaring himself king, executing Sa Wang Ji—the rightful heir—and taking palace women for himself. Jen Chao was charged with committing many crimes and losing the people’s favor. Several independent states were reported to be allied in opposing Jen Chao to restore the country.

Li Siyue praised Mo Su Lin for his efforts to protect the people from danger. Because Emperor Qianlong did not fully understand the true situation in Siam, he had sent envoys to investigate. Upon receiving Mo Su Lin’s report, the emperor regarded Jen Chao as a dangerous figure causing chaos by claiming kingship.

On July 4, Li Siyue received an imperial order to return the original letter meant for Siam back to the imperial capital. Li Siyue reported to Emperor Qianlong that the true Siamese heir had not yet been found, but Mo Su Lin, governor of Hechian, was humble and respectful toward the emperor. Mo Su Lin had captured Sansewen and was gathering other states to oppose Jen Chao. This demonstrated Mo Su Lin’s considerable power and his role in resisting the Burmese, acting in accordance with the emperor’s commands.

On July 5, 1769 (B.E. 2312), Li Siyue acted according to his own judgment by sending a bandit unit led by Chai Han to Hechian. He sent a letter along with silk and clothing to Mo Su Lin. The letter was a copy of an imperial edict from Emperor Qianlong addressed to the King of Siam, requesting Siam to help fight against Burma. However, the Chinese emperor did not approve of Li Siyue’s actions.

On July 14, Emperor Qianlong sent a letter to Li Siyue stating that Siam had been unable to find a legitimate heir, and the real power lay with Jen Chao (Gan Enle). It was difficult to find the original heir to reunify the country. From then on, Siam was governed by a powerful figure, and the Chinese court changed its previous attitude toward Siam, as China did not want to become involved in Siam’s internal turmoil.

On July 18, Li Siyue sent Emperor Qianlong’s letter to Mo Su Lin, informing him that Siam was too distant for China to control. He opposed Jen Chao’s usurpation and military campaigns, arguing that preventing Jen Chao from uniting the country was necessary. However, Mo Su Lin was also attempting to seize power in the country. According to a report from the Chinese general fighting Burma, Mo Su Lin was praised for his efforts to save the nation.

In November, Jen Chao captured the city of Lue Kwen, then began sending troops to attack Mo Su Lin’s territory, reclaiming Sansewen. The following year, he also recaptured Husilu. Jen Chao governed northern Siam and, in fact, had largely reunited the country.

On December 4, a Chinese naval commander arrived in Hechian. Mo Su Lin sent an official to take his letter to Guangzhou for presentation to the Chinese emperor. The letter stated that Siam had no king, the heir was lost, and only two or three powerful officials remained, though they held no real power. Mo Su Lin asserted that he had done his best.

Li Siyue, governor of Guangdong and Guangxi, replied to Mo Su Lin acknowledging receipt of his letter and recognizing his efforts. Nevertheless, Li Siyue expressed confusion as to why, when the Siamese king was in danger and Sa Te Le fled to Hechian, Mo Su Lin refused to help reunify the country. Mo Su Lin had captured Sa Te Le but would not send him back to the capital. Despite repeated requests from the emperor for reports on the situation, Mo Su Lin had not responded and seemed concerned only with his own interests, requesting help for himself rather than working to reunify Siam. Li Siyue’s attitude began to shift toward suspicion and dissatisfaction with Mo Su Lin.

In May 1770 (B.E. 2313), during Emperor Qianlong’s 35th year, Chai Han, the Chinese bandit leader, sent a letter to Jen Chao requesting assistance in capturing the Burmese king. In December of the same year, Jen Chao recaptured “Qingmai” (Chiang Mai), which was held by Burma. According to testimony from a Thai official named Kun Mishi Necha (identity unclear), Jen Chao led 40,000 troops to besiege Qingmai, joined by 20,000 troops from the eastern provinces. After several days of siege, lacking food and gunpowder, they retreated.

During the campaign, Jen Chao captured 10 men and 41 women from Qingmai, along with maps, and handed them over to four Chinese generals named Houpa Chanop Huansidu, Kuan Mi Jershixi, Hou Xuantuanwanni Suxi, and Xie Kaichuan (the Thai equivalents of these names are unknown).

On June 9, Chai Han returned to Guangdong to deliver letters to Mo Su Lin and Sa Te Le for presentation to the Chinese emperor. Mo Su Lin’s letter reported that he had fulfilled the emperor’s wishes and had urged neighboring states to help prevent and destroy Burma. He had also united allied states to assist China against Burma. However, Jen Chao had captured Lue Kwen and attacked Mo Su Lin’s cities to seize gifts given by the emperor the previous year, despite Mo Su Lin’s having sent Sa Te Le to Jen Chao.

On July 26, 1771 (B.E. 2314), Houpa Chanop Huansidu and others arrived in Nanhai, Guangdong province, and requested Wu Wu Han, the local governor, to report to Li Siyue. They reported that two men and ten women had died en route, leaving 39 survivors.

According to the testimony of the captured governor of Qingmai, Neqie Tudientha, he had served under the prince of Ava named Suina Yanmaageli. Together they captured and held Qingmai. The Ava prince appointed the father of a consort as governor of Qingmai, named Naniu Ge Manhijiaozhe, with Neqie Tudientha serving as an official responsible for defending the Wanni Guoqili area. During that year, Siam sent troops to retake Qingmai, where Neqie Tudientha was wounded by gunfire and subsequently captured.

Li Siyue selected four of the eldest male captives and four of the eldest female captives to be sent to the capital for interrogation by the royal court. Meanwhile, Neqie Tudientha and 12 others were sent to be slaves in Helongjiang, according to the rules of prisoner handling in Guangdong province. The remaining 27 women were sent to be slaves around that city. Afterward, Houpa Chanop Huansidu traveled back to deliver a letter from the governors of Guangdong and Guangxi to Jen Chao. The letter stated that the Emperor of China believed the special royal seals given to the previous kings were likely lost during the Burmese invasions of Siam. Thus, the emperor requested that Jen Chao be granted the opportunity to offer tribute once again, as the Siamese were still pleasing to the emperor. This letter showed that Jen Chao sought to please the Chinese emperor by sending captives to China.

On August 17, the Chinese emperor received a report from Li Siyue and sent a letter to him stating that since Jen Chao sent Burmese captives as a sign of loyalty and wished to offer tribute, the emperor would not refuse his request. The emperor would allow Jen Chao to send tribute because he demonstrated loyalty and followed Chinese protocols. Therefore, the emperor considered sending garments to Jen Chao.

On September 7, Li Siyue received the imperial letter and prepared two types of fabric, two rolls each, to send to Jen Chao. On October 18, the emperor sent another letter to Li Siyue, expressing concern about the continual strife and conquest among small states. He cited the example of Annam (Vietnam), which had changed kings many times, and noted that Siam was now under Jen Chao’s control after the Burmese invasion. However, since Jen Chao had done what was requested—sending troops to attack Chiang Mai and capturing a Burmese general—this showed he was hostile to Burma and remained respectful to China. Therefore, the emperor advised against further resistance and urged not to treat Jen Chao differently despite his lack of royal bloodline. Since Jen Chao was rebuilding the country, China should not oppose his sending tribute. Opposing him might push him to ally with Burma, which would be unwise. The emperor instructed Li Siyue to inform Jen Chao that he would be granted a title.

At the same time, Fu Ren, a Chinese official, returned to China after being defeated by the Burmese and failing to negotiate a treaty. The Burmese king was proud and stubborn, refusing to heed China. Aware of this situation, the emperor decided to cooperate with Siam.

On October 6, 1771, in the 36th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, Jen Chao sent an army to attack Hechian, appointing Chen Lian (known in Thai history as Phraya Phichai Racha) as the commander and the ship captain Yang Jinzhong (known as Phraya Yommarat, though in Thai chronicles the army that attacked Sawankhaburi was a land force, and King Taksin himself led the navy) as the vanguard commander. Due to Mo Suoling’s insufficient military strength, he was defeated on October 9. Mo Suoling fled to a place called Luxian in Annam (Vietnam), though the exact location is unknown. All weapons and people, including Saoter, were captured by Jen Chao’s forces. Jen Chao requested Chen Lian to stay in control of Hechian.

In May 1772, the 37th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, Jen Chao sent prisoners to China and wrote to Li Siyue explaining that the previous winter he had sent troops to attack Ben Di Bay and discovered 35 Chinese people there from Guangdong province, near Guizhou and Haiphong. These people had migrated to Yangjiang to farm in 1767 during Emperor Qianlong’s reign but had lost their way and ended up in Ben Di. They asked the local governor for help to return home, but Mo Suoling refused to send them back, so they had stayed there for six years. Jen Chao provided them with rice, water, food, and money. Among them, two men—Chen Junqing and Yang Sangquan—were sent back by ship to Guangdong. One ship, captained by Su Yuanchen, carried Yang Sangquan, nine men, and eight women. The other ship, captained by Qi Pu, carried Chen Junqing, 12 men, and four women.

On June 6, Yang Sangquan arrived in Guangzhou and reported to the governor of Guangdong, but his report differed from Jen Chao’s letter. He stated he did not go to Yangjiang to farm but had worked as a servant and knew Ben Di had enough land for farming, so he persuaded his family to rent a ship, captained by Hu Longzhong, and traveled overnight. Mo Suoling did not force them to stay. Li Siyue suspected that since Mo Suoling and Jen Chao had long been enemies, Jen Chao likely seized the bay and, fearing Mo Suoling would report this to the Chinese emperor, accused Mo Suoling of imprisoning Chinese people to damage his reputation. Meanwhile, Mo Suoling tried to keep the rightful heir, Saoter, with him to maintain power. Since the Chinese emperor had sent a letter this year, if Mo Suoling could keep the heir, he could control the country. But Jen Chao learned of this, and Li Siyue did not want to dispute with Jen Chao or report this to the emperor, because Jen Chao was not the legitimate heir.

Li Siyue sent a letter to Mo Suoling urging him to do his best to help himself and his people gain respect, noting that although Jen Chao was not the leader, he showed respect to the emperor and asked for a special royal reward. This shows Jen Chao tried to please the Chinese emperor and sent tribute multiple times, while Mo Suoling attempted to win the emperor’s favor and discredit Jen Chao, causing the Chinese court to become biased against Jen Chao. Thus, Mo Suoling and Jen Chao often opposed each other.

When Mo Suoling marched to send Saoter back to the capital, his army was attacked by Jen Chao’s forces near Zhanjiaowan, and most soldiers were wounded, forcing a retreat to Hechian. According to Mo Suoling’s report to China, his city was defeated because heaven did not protect it. He stated a Chinese official named Jen Chao tried to attack his city, and in 1768 he received orders from the Chinese emperor to investigate the special seal originally granted by China. Chinese officials came on the ship Mogongyi, which disappeared near Liukuan (Nakhon Si Thammarat). The Chinese captain Yang Jinzhong tried to cooperate with Jen Chao in Hechian to obtain the seal. Mo Suoling always followed Chinese rules, but if the true heir wanted to reunify the country and requested the seal, he would grant it. Jen Chao was not the true heir and requested the seal and Saoter and Sesu (the heirs) multiple times. Mo Suoling believed only three heirs remained: Sa Wangji, who was killed by Jen Chao; the princess, married to an official; and Saoter and Sesu, whom Mo Suoling protected. He could not kill them but defended them and opposed Jen Chao.

Regarding the seal issue, it originated on April 14, 1766, the 31st year of Emperor Qianlong, when the King of Ayutthaya sent the official Phraya Kaetong Ho to Nanjing, the Chinese capital. The Chinese emperor granted a special seal and gifts, including colored cloth, jade, gold, and fine porcelain. At that time, Ayutthaya was defeated by Burma. The envoy told the Chinese emperor the king had died and took these gifts to Guangzhou. On October 30, 1768, the envoy sailed back to Siam. Jen Chao needed the seal to offer tribute to the Chinese court because the China-Ayutthaya relationship was like lord and vassal. When Mo Suoling returned the seal to Guangzhou, Sino-Siamese relations broke down. When Jen Chao reunified the country and wanted to offer tribute to the Chinese emperor but lacked the seal, he was angered at Mo Suoling for returning the seal.

The details of the fourth royal diplomatic contact.

On August 4, 1774, in the 39th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, Chang De, an official from Nanhai, Guangdong Province, reported that a merchant ship belonging to Chen Fuchen was bound for the country of Fo Luo but, due to adverse weather, the ship was blown off course into Siam. A Siamese official brought the ship to Guangzhou and sent a report stating that Jen Chao had been earnestly seeking to avenge the previous king by resisting Burma. Since the territory was near the sea but could not secure enough weapons, Jen Chao requested to purchase 50 loads (ha) of sulfur (approximately 150,000 kilograms or 150 metric tons) for making gunpowder and 500 iron pans (for casting cannons).

Li Siyue noted that Jen Chao had ruled Siam for seven years, still residing at Wang Ge (likely Thonburi) and had not returned to the old capital. Reports indicated Jen Chao was trying to acquire more weapons to defend against opposing states. Jen Chao sought to win favor with the Chinese emperor to gain trust. China recognized Jen Chao’s efforts to defend Siam’s borders and therefore should not prohibit him. From this, Li Siyue drafted a memorial to Emperor Qianlong for review, stating it was commendable that Jen Chao sought revenge, and while he understood Jen Chao’s need for weapons, he cautioned him not to forget the former king and to avenge for him. However, according to Chinese law, sulfur and iron pans could not be sold to anyone without a special imperial decree. The memorial bears a red-ink note from the emperor approving Li Siyue’s draft.

Jen Chao had established a new capital at Thonburi, but Li Siyue misunderstood the real situation and thought Jen Chao was afraid to enter the old capital. That year, Siam and Burma were again at war, and Siam needed a large number of soldiers and sulfur because Siam only produced potassium nitrate (saltpeter), not sulfur. Therefore, Jen Chao sought to buy sulfur from China.

A Chinese man named Yang Chaopin, who was sent back to Yunnan, reported that in April 1770 (the 34th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign), he went to Muan Si (in Cambodia), which was controlled by the “Mian Su” (Vietnamese), often called Ta Ma (Phutthaisong), located near the sea. There were over 10,000 people there, but it was controlled by the Mian Su. In the 39th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign (1774), the Mian Su attempted to invade Siam. Jen Chao requested 1,000 people from Muan Si and asked Muan Si to provide and send supplies. He also requested silver ore, but Muan Si was unable to comply due to great difficulties.

The Mansu killed the general of Miensu and fled to Burma. Later, Miensu sent an army to seize Mansu, reaching the city of Mê Phu (Phutthayaphet). Battles were balanced, with wins on both sides. Mê Phu, a wide plain, was hard to conquer. Nearby, the area called “La Pho” (Baphnom), with many hills, was better for fighting. The battle moved to “Koe Phua” (Kampot). Miensu camped around the hills and besieged for one month. The Siamese won, captured 6,000–7,000 prisoners, and brought them to Siam.

The details of the Fifth Royal Diplomatic Contact

In August 1775 (B.E. 2318), year 40 of Qianlong’s reign, a merchant named Chen Wan Shen (or Chen Wan Sen) brought a letter from Chen Jia to the Chinese emperor. It said Chen Jia defeated Ching Mai (Chiang Mai). People from Da Ma (Dali) were captured, including 19 soldiers from Yunnan, one named Xiao Chen Zhang. Because war with Burma continued, Chen Jia asked the emperor for permission to buy weapons.

Li Shiyao doubted Chen Jia’s letter. He questioned people sent back by Chen Jia. They said that in August last year, Burma attacked Da Ma and fought to Siam’s border, differing from Chen Jia’s story. But since Chen Jia sent Chinese back to Yunnan, showing loyalty to the emperor, the emperor agreed to sell sulfur and iron pans as before, but no cannons. The emperor told Li Shiyao to write a reply to Siam.

The details of the Sixth Royal Diplomatic Contact

In 1776 (B.E. 2319), year 41 of Qianlong’s reign, merchant Mo Guangyi brought Chen Jia’s letter with Yang Chaopin and Zuan Yijin to China to return to Yunnan. Chen Jia wrote Siam fought Burma many years and asked to buy 100 loads of sulfur (about 300,000 kg). He asked if China planned to attack Ava, to tell Siam to help attack Burma from another side. The three sent were merchants asking passes to sell goods in Mupang. They were caught by Burma going to Ava, escaped to Mansu, then fled to Siam.

On October 10, 1776, Li Shiyao drafted a letter to report to the imperial capital. The Emperor of China ordered Wu Minzhong, a general, to send a letter to Li Shiyao stating that when Chen Jia encountered Chinese people in Siam, he would help them by sending them back to China as a gesture to please the Emperor. Previously, the Emperor allowed him to buy sulfur and iron pans, and this time permission was granted again for the same quantity. Li Shiyao then sent this letter to inform Chen Jia that after he unified the country, initially he sought a special royal seal from the Emperor. Afterwards, he aided China by fighting Burma, capturing a Burmese general who had taken Chiang Mai, and sending him to China. He also sent Burmese captives to China. These actions showed loyalty to the Emperor. Chen Jia’s military strength grew, and he sent armies to attack Burma, thus requiring more weapons and war materials such as sulfur and iron pans from China. Since Chen Jia acted carefully and humbly toward the Emperor, Li Shiyao permitted the purchase of weapons.

The details of the Seventh Royal Diplomatic Contact

In April 1777, the 42nd year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, Li Shiyao drafted a letter for the Emperor’s consideration to send to Chen Jia. The letter stated that it was known Chen Jia continued to request a special royal title so he could rule the country. Li Shiyao recalled that previously the Emperor ordered that foreign rulers seeking special titles to offer tribute did not need to send large amounts of tribute. Therefore, if Chen Jia tried to send more tribute, Li Shiyao was to carefully observe the situation and report back. At first, Li Shiyao suspected Chen Jia was consolidating power within his country and intended to use the special title from China to legitimize his authority. This seemed true since no one had witnessed the battles with Burma directly, but Li Shiyao believed it because testimony from a certain official named Zun Puo Qiang and a local named Yang Chaoping agreed that Chen Jia had killed many Burmese. Merchants traveling by sea also reported that Chen Jia’s closest ally was a major enemy of Burma. This suggested an effort to persuade Chen Jia to send tribute to the Emperor as a way to gain recognition as the legitimate King of Siam.

At that time, relations between Burma and China were poor, and the Qing dynasty’s army had suffered defeat. Li Shiyao, as governor of the two provinces of Guangdong and Guangxi and trying to control Yunnan and Guizhou, sought to encourage Siam to send tribute, aiming for Siam to assist China in attacking Burma from the rear. The Emperor approved this plan but did not wish to send a direct letter himself; instead, he instructed Li Shiyao to send a letter to Chen Jia. The Emperor ordered Yang Jingsu to lead the letter to Siam.

In June of the 42nd year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign (1777), Chen Jia sent Phraya Suay Thuan Ya Phai Na Thu (Phraya Sunthorn Aphairacha, the royal envoy) to Guangdong to respectfully request the imperial permission for Siam to send tribute. At this time, the Chinese officials considered Chen Jia to be very loyal, but Siam was unable to locate a legitimate heir to the throne. Consequently, China began to recognize Chen Jia and permitted Siam to send tribute. However, Siam was very poor then, lacking items in the royal treasury to offer as tribute, due to ongoing wars with Burma and the process of unifying the country. Therefore, Chen Jia petitioned to postpone sending the tribute.

On June 29, the leader of a guerrilla force named Chen Dayang from Guangzhou, Guangdong, reported that a merchant ship had departed Siam returning to Guangdong. On board were three Siamese officials carrying tribute for the Chinese emperor, accompanied by 15 soldiers and 6 Burmese captives. Li Shiyao delayed sending any letter to Chen Jia, expecting to send it together with this diplomatic delegation. At that time, Guangdong had a new provincial governor, Yang Jingsu, who assigned an official named Biao Pian to receive the three Siamese officials.

On July 1, the Siamese officials brought Chen Jia’s letter to present to the Chinese emperor. Yang Jingsu informed the Guangzhou governor, Li Shuying, to welcome the Siamese officials: Phraya Suay Thuan Ya Phai Na Thu (the royal envoy) and two others. They were also questioned for details, which included Chen Jia’s efforts to avenge the former king, his desire to please the Chinese emperor, and plans to offer tribute to strengthen his authority, gain recognition from neighboring states, and assist in fighting Burma. This was the reason why the three officials were sent to China. The previous year, Siam had captured 300 Burmese prisoners in battle; however, some had died gradually, and the remaining were sent to China. Among these captives were Ai Ke, Ai Suai—close officials to the governor of Ava—and Ai Yao, a servant of Ai Ke. According to Chinese law regarding foreign captives, they required special imperial orders before Siamese officials could bring them as tribute.

Since Chen Jia had ruled Siam, he had not yet received a special title from the Chinese emperor. He had been trying to send letters with tribute, showing great respect. The special imperial seal once granted during the Ayutthaya period was lost when Ayutthaya fell to Burma the second time. Without this seal, the Qing dynasty could not officially recognize Chen Jia as king. Li Shiyao initially opposed Chen Jia, but the new governor, Yang Jingsu, compiled an inventory of the tribute Chen Jia sent. Following Chinese protocol but uncertain how to proceed, Yang Jingsu reported to the emperor that Siam had long been under Chinese suzerainty, and the Thai king had received a special seal from the Chinese court. Due to Burmese invasions, Chen Jia restored the country, avenged China by driving out and killing many Burmese, and sent a letter requesting a special title. He also returned Chinese people captured by Burma to China. These actions demonstrated Chen Jia’s respect and loyalty to the Chinese emperor.

Foreign conflicts and throne overthrows were common, but this Siamese case was different because Chen Jia was of Guangdong origin. Initially, the Chinese emperor could not accept Chen Jia as king. Later, multiple imperial letters instructed the governor of Guangzhou that if Chen Jia sent letters requesting a special title, they must be reported to the capital immediately. The emperor promised to grant the special seal. Chen Jia sent such a letter again, but instead of reporting directly to the emperor, Yang Jingsu drafted an old-style report. The emperor was displeased.

Therefore, on July 24, the emperor sent an official named Gong Aowei to assist Yang Jingsu, reprimanding him for neglecting previous reports and for failing to investigate prior governors’ actions. Gong Aowei was appointed to help draft and copy reports; the original was given to the Siamese envoy to present to the emperor. The letter stated that in spring, Li Shiyao was transferred to govern Yunnan and Guangzhou and had told Gong Aowei that the former Thai king died during war, and Chen Jia restored the country. Chen Jia was greatly respected by the Thai people. Though not the rightful heir, he controlled and ruled the country, striving to gain the Chinese emperor’s trust. If Chen Jia requested the governor of Guangdong to send reports to the emperor, Guangdong would consider them carefully. Guangdong was aware of previous protocols and now welcomed Chen Jia’s tribute. Once tribute arrived, Guangdong would report it to the capital. It was understood that Chen Jia desired the emperor’s favor to help govern Siam. Guangdong realized Chen Jia wanted a special title from China but had not declared this openly. This caused Guangdong to withhold reporting. However, if Chen Jia prepared tribute and sent envoys with explanations about the former king’s heir and requested Guangdong to report it, Guangdong would willingly do so immediately.

This letter was delivered to the Siamese envoy Phraya Suay Thuan Ya Phai Na Thu on August 6, along with gifts of food and silk. Chinese officials from Nanhai accompanied the envoy to the ship when departing for Siam on August 10.

According to the Gongting Zhaji (Imperial Court Annals), in the 11th month of the 42nd year (1777), Siam sent an envoy to the Chinese capital to pay respects to the emperor and requested a Chinese princess in marriage. However, no evidence of this exists in either Thai or Chinese annals.

When Chen Jia sent envoys in the 33rd year (1771), Emperor Qianlong granted a special title. The envoy stated that if Chen Jia was granted the title, he could serve the emperor, and Siam’s people would unite under him, enabling attacks on Fu Sulu, Lu Kuan, and Gao Liea. Chen Jia would prepare ships to bring gifts to China and pledge loyalty. Even if the Siamese crowned Chen Jia king, without the special title from China, he would not be considered the rightful ruler, and neighboring countries would refuse to acknowledge him.

In the 42nd year of Qianlong’s reign, the Siamese envoy Phraya Suay Thuan Ya Phai Na Thu informed China that Chen Jia sought to avenge the former king and deserved authority through recognition by the Chinese emperor. Continued tribute from Siam would ensure acceptance by neighbors and strength to fight enemies. Chen Jia planned to be accepted by all Siamese people and maintain a strong army in Southeast Asia, avoiding conflicts with neighbors but requiring acceptance by the Chinese emperor. China allowed tribute to be sent. Thus, it is clear Chen Jia’s repeated attempts to send tribute were primarily for political benefit.

When the Siamese envoy arrived at the Chinese court, they were welcomed by the emperor. The Chinese court followed the tribute protocol and prepared gifts for the envoy to take back to Chen Jia. However, Chen Jia still had not received an official title from China.