King Taksin The Geart

Chapter 14: King Taksin’s Royal Duties in Transportation and Relations with Western Countries

14.1 Royal undertakings in transportation: Why were roads built and canals dug during the Thonburi period?

King Taksin the Great abolished the old belief that the construction of roads and improvement of communication routes would benefit enemies and rebels. Instead, His Majesty viewed them as advantageous primarily for commerce. Thus, during the winter months, when warfare had subsided, the King would command the construction and maintenance of roads to facilitate overland travel, trade, and the transportation of goods. He also ordered the excavation of canals to serve as thoroughfares for merchants and commoners, enhancing commercial convenience, the delivery of goods, and general travel and communication, as well as serving strategic military purposes (Praphat Treenarong, 1999: 20).

This undertaking was attested by a record from the French Catholic missionaries who resided in Thonburi at the time (Chronicles, Volume 39), which states:

“…During the winter season, King Taksin ordered the building of roads, which contravened the traditional royal customs of former monarchs. He also commanded the construction of numerous fortresses…”

In those days, more than 200 years ago, the principal routes of transportation throughout Siam were almost exclusively by water. References to roads were exceedingly rare, the only notable exception being the “Phra Ruang Road” from the Sukhothai period. Therefore, it may be said that King Taksin harbored an enlightened and progressive vision for national development.

14.1.1 The Excavation of Moat Canals on the Western and Eastern Banks

When His Majesty King Taksin the Great established Thonburi as the royal capital, its domain extended over the eastern bank as well (present-day Bangkok or Phra Nakhon). Thonburi was initially a city without walls. To secure its perimeter, wooden stockades made from whole thonglang (Erythrina) trees were erected along the canal encircling the city on both sides of the river.

In the year 1772 (B.E. 2315), His Majesty issued a royal decree for the excavation of canals as follows, as recorded in the Royal Chronicles:

“…Then ordered the digging of a moat behind the city, from Khlong Bangkok Noi to Khlong Bangkok Yai (according to the astrologers’ chronicle, this took place in the year Chulasakarat 1135, corresponding to B.E. 2315). This likely refers to what is known today as Khlong Ban Khamin, Khlong Ban Mo, and Khlong Wat Thai Talat (Wat Molilokkayaram), which all flow into Khlong Bangkok Yai. The excavated soil was piled up to form ramparts along the three landward sides, with the riverside remaining open. Stockades were erected on the eastern bank as well. A moat was dug behind the city walls, beginning at the old wall behind Fort Wichayen, looping to the Guardian Spirit Shrine at the promontory, and opening to the river on both the northern side near Tha Chang (Front Palace Pier) and the southern side at the mouth of Khlong Talat. Earth from the excavation was heaped into embankments on all three land-facing sides. Bricks were taken from Fort Pho Sam Ton, Fort Si Kuk, Bang Sai, and Mueang Phra Pradaeng to construct walls and fortifications along the embankments. The riverside was left open, using the river as a natural barrier—just as was done at Phitsanulok (the ‘City of the Broken Chest’).”

(N. na Paknam, 1993: 53)

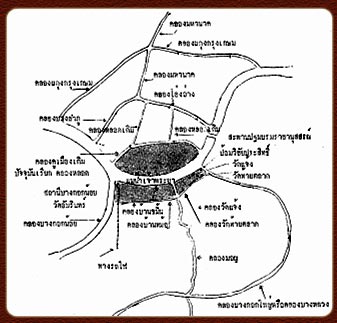

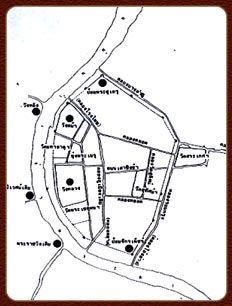

Map showing the boundaries of Thonburi when it was the royal capital:

Western Thonburi bordered Khlong Ban Khamin, Khlong Ban Mo, and Khlong Wat Thai Talat.

Eastern Thonburi bordered the city moat, now known as Khlong Lot.

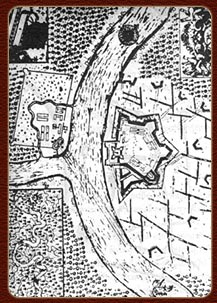

The area around the forts on both sides of the Chao Phraya River, at the mouth of Khlong Bangkok Yai, during the Ayutthaya period in the town of Bangkok

(Image from the book “Wiang Wang Fang Thon: Communities of the Siamese People”)

Note: What is now called Khlong Ban Khamin on the Thonburi side was originally part of the western city moat of Thonburi, connecting Khlong Bangkok Noi and Khlong Bangkok Yai. Today, Arun Amarin Road follows this route, but the canal has become overgrown and polluted, losing its defensive role due to encroaching buildings.

Fort Wichaiyen, once located behind the royal palace, was later renamed Fort Wichaiprasit by King Taksin.

(Thonburi Facts, 2000: p.88)

The eastern moat, on the Bangkok side, was dug during King Taksin’s reign and connected the Chao Phraya River from Pin Klao Bridge to Pak Khlong Talat. Known as Khlong Lot, it still shows remnants of old brick walls and is lined with trees. However, modern roads and bridges now cross over parts of it. (Sujit Wongthes, 2002: p.60)

It was officially renamed “Khlong Khu Mueang Doem” (Original City Moat) in 1982 during the 200th anniversary of Rattanakosin. (Sansanee Wirasinchai, 1995: pp.38–39)

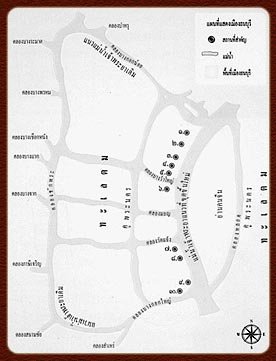

Map Showing the City of Thonburi

Wat Amarinthararam

The Rear Palace

Mangosteen Garden Palace

Ban Phun Palace

Wat Rakhang Kositaram

The Royal Residence

Wat Arun Ratchawararam

Thonburi Palace (Old Palace)

Wichai Prasit Fort

Wat Molilokkayaram

(Image from the book “Interesting Facts about Thonburi”, 2000: p. 87)

When King Rama I (Phra Phutthayotfa Chulalok the Great) established Bangkok as the new capital, he commanded the excavation of a new city moat parallel to the original moat on the Bangkok side in order to expand the capital’s boundaries. Consequently, the original moat was no longer used for defensive purposes and gradually became a transportation route for city residents. People began to call different sections of this canal according to nearby landmarks. For instance, the northern mouth of the canal passed by the Royal Silk Factory and was thus called “Khlong Rong Mai” (Silk Factory Canal). The southern mouth of the canal passed through a bustling land and floating market area and became known as “Pak Khlong Talad” (Market Canal Mouth). The central section between the Khlong Lot by Wat Buranasirimat and the Khlong Lot by Wat Ratchabophit was officially named “Khlong Lot” (Tube Canal) by a public health department decree in R.S. 127 (1908), likely because it connected two larger parallel canals like a tube. Over time, however, people came to refer to the entire canal line simply as “Khlong Lot,” which is technically incorrect based on the original names and purposes of each section.

In summary:

On the west side of Thonburi, the King ordered the digging of a canal connecting Khlong Bangkok Noi and Khlong Bangkok Yai. The remnants of this canal can still be seen today and are called Khlong Wat Wiset, running parallel to today’s Arun Amarin Road. On the east side (the Phra Nakhon side), he ordered the digging of the city moat from the present-day Pom Pak Khlong Talat area to the Chao Phraya River near the present-day Phra Pinklao Bridge in front of the National Theatre, now commonly called Khlong Lot. Thus, the “Khlong Lot” in front of the Ministry of Interior is the eastern moat of Thonburi, and “Khlong Wat Wiset” is the western moat of Thonburi. Significantly, the Chao Phraya River runs through the middle of the city, leading to Thonburi being nicknamed the “Broken Chest City” (Muang Ok Taek). (Source: Sujit Wongthet, 2002: 26)

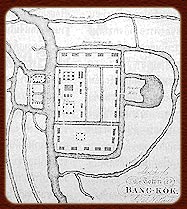

Map of Bangkok City, published by Henry Colburn, London, June 1828

(Image from Silpa Watthanatham Journal)

The atmosphere of Khlong Lot in the past — used for transportation and trade

Currently, its function is as a drainage canal. (Image courtesy of the Drainage Department)

Note:

During the reign of King Rama I (Phra Buddha Yodfa Chulalok), additional canals were ordered to be dug in 1783 (B.E. 2326) connecting the old city moat canal and the outer city moat for strategic and transportation purposes. There were two such canals, though no official names were given; they were generally referred to as “Khlong Luad” (Thread Canals) based on their characteristics.

The Khlong Luad near Wat Ratchanadda started from the old city moat canal, between the Royal Hotel (now Rattanakosin Hotel) and Wat Boran Sirimattharam. It passed Tanao Road, Wat Mahannoparam, Ban Dinso Road, the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration Hall, Wat Ratchanadda, and Maha Chai Road before joining the outer city moat canal at Wat Ratchanaddaram. This canal was originally called Khlong Luad without a specific name but later came to be referred to by the areas it passed through, such as Khlong Boran Sirirat, Khlong Wat Mahannop, Khlong Wat Ratchanadda, and Khlong Wat Thepthida, etc.

Map of Bangkok during the reign of King Phra Buddha Yodfa Chulalok (Rama I)

(Image from Modern Thai History)

Khlong Luad Wat Ratchabophit begins from the old city moat canal near Wat Ratchabophit, passing through Ratchabophit Road, Ban Dinso Road, and Maha Chai Road before joining the outer city moat canal north of Damrong Sathit Bridge. This canal is also known as “Khlong Saphan Than,” but its official name is “Khlong Wat Ratchabophit.”

On the occasion of the 200th anniversary of the Rattanakosin era, the government under King Bhumibol Adulyadej (Rama IX) passed a cabinet resolution on June 13, 1967 (B.E. 2510) to officially name these two canals as a way to preserve historical landmarks: “Khlong Luad Wat Ratchanaddaram and Khlong Luad Wat Ratchabophit.” (Source: Canal System Division, Drainage Department, Bangkok Metropolitan Administration, 2003, http://dds.bma.go.th/Csd/canal_1.htm, accessed 8 July 2004)

14.1.2 Additionally, His Majesty also ordered the excavation of canals in the city of Nakhon Si Thammarat, as stated below:

“In terms of canal excavation, there is evidence found in the royal decree appointing King Khatthiyarach Nikhom Somdet Maihasawan as King of Nakhon Si Thammarat in 1776 (B.E. 2319). It states that he was instructed to expedite the digging of Tha Kham Canal to connect to the sea on the west side, which today we call the Indian Ocean. This was to facilitate maritime trade routes and the supply logistics for the navy on the western sea.”

The decree reads: “…One point is the Tha Kham Canal, which leads to the western sea. An order was previously issued for it to be excavated but remains unfinished. Keep this in mind as an order will be issued again later…”

This shows that during the Thonburi period, Thailand’s transportation development included both road cutting and canal digging simultaneously. The practice of road construction in the Rattanakosin period began notably during the reign of King Rama IV.”

(Sathuon Supasopon, 1984: 52)

14.2 Royal Duties in Relations with Western Hemisphere Countries

ChatGPT พูดว่า:

During the reign of King Taksin, Siam (Thailand) established diplomatic and trade relations with several Western countries, including Portugal, the Netherlands, England, and France, primarily focusing on commerce. Meanwhile, Eastern countries trading with Thonburi included China, Java (then known as “Guests from the city of Yakkhattra,” referring to present-day Indonesia), and the Malay Peninsula (Malaysia), among others. These trade interactions brought significant revenue to Siam through port fees and import-export taxes under the taxation system of that era.

Some historians regard the Thonburi period as an era of flourishing trade for both the common people and the royal court. Maritime trade was especially important, with goods loaded onto junks and merchant ships to be exported to various countries in the region. As the country gradually stabilized, King Taksin took great care to promote and develop maritime commerce, recognizing it as the most effective way to generate substantial income for the nation’s treasury, ensuring sufficient funds for royal expenses.

Historical records show that during this period, Siam sent royal junks on multiple trading routes, extending eastward to China and westward to India. At times, as many as 11 royal junks were dispatched simultaneously—a considerable number for that era. The profits from maritime trade greatly alleviated the tax burden on the common people.

ChatGPT พูดว่า:

Maritime trade during this period was a crucial part of rebuilding the Thai nation. Beyond the basic goal of generating profit, it fostered a love of commerce among the Thai people, who became increasingly skilled and expanded their trading activities farther and farther. This also helped prevent trade from falling entirely into foreign hands, allowing Siam to protect the interests of local products and prevent them from being neglected. It marked a time of significant commercial prosperity in Thai history. (Sanun Silakorn, 1988: 37)

French Junk (Ship) Indian Junk (Ship)

(Image from the book: Ships — The Culture of the Chao Phraya River Basin)

Japanese Junk (Ship)

(Image from Silpa Watthanatham Journal)

14.2.1 Trade Relations with Portugal

During the Thonburi period, there was some trade contact with the Portuguese. In the year 1790 (B.E. 2333), the Portuguese and Moors from Surat (a city in India), which was then a Portuguese colony, traveled to trade with Siam. Siam also sent royal junks to trade in India, reaching as far as Goa and Surat. However, there was no formal diplomatic relationship established between the two nations at that time. (From “53 Thai Monarchs: Their Hearts Belong to the Thai People,” 2000: 246)

Portuguese Junk (Ship)

(Image from the book Ships: The Culture of the Chao Phraya River People)

English Junk (Ship)

(Image from the book Ships: The Culture of the Chao Phraya River People)

14.2.2 Trade Relations with England

During the reign of King Taksin the Great, efforts were made to acquire modern weaponry for use in warfare.

The most important country from which Thailand procured weapons was England, which at the time had its center of power in India and was expanding its influence to control the Malay Peninsula (present-day Malaysia and Singapore). England sought to establish a trading port on the peninsula to compete with the Dutch, using it as a harbor for both warships and trading vessels. A key figure in this effort was Francis Light (also known in historical Thai documents as “Captain Lek” or “Captain Steel”), a former officer of the British Royal Navy.

Francis Light (Captain Francis Light)

(Image from http://www.thum.org/albums/penang03/0006_Statue_of_Sir_Francis_Light.jpg)

Francis Light resigned from the British Royal Navy to become an important merchant captain for the East India Company, which was a powerful British trading company at the time. He frequently sailed and traded in the region, building close relationships with the Malay people, becoming widely known and respected. He also lived for a long time in Thalang (now Phuket), where he married a Thai woman of Portuguese descent and became well acquainted with local leaders such as Phraya Thalang and Khun Ying Chan (Thao Thep Kasattri), the heroic woman of Thalang.

Because of his wide reputation and connections in both trade and high society throughout the region, King Taksin appointed Captain Francis Light to handle the procurement of weapons for the Thai government. Official correspondence authorizing this was issued in 1777 (B.E. 2320). Light managed the task quite well.

In a letter dated June 23, 1777, written by Francis Light to Mr. George Stratton, he described King Taksin’s desire to purchase firearms, saying:

“…The King of Siam has heard that the Burmese are closely allied with the French. While he is not afraid of the Burmese alone, he fears they will join forces with the numerous French in Hongsawadi and Ava. Therefore, he sees a great threat coming. Even though he has already purchased 6,000 guns from the Dutch in Batavia at 12 baht each, with an additional 1,000 guns expected this year, the King does not wish to be involved much with the Dutch. He therefore asked me to procure as many small arms as possible, and I promised to try my best. The King also said his army will attack Mergui this season…”

According to royal chronicles and handwritten letters, in 1776 (B.E. 2319), Captain Light sent 1,400 muskets to King Taksin, along with other royal gifts:

“Furthermore, in the tenth month, the English Captain Lek of Ko Mak sent 1,400 muskets along with various royal tribute items.”

There is also evidence that the Prime Minister of Finance (Chao Phraya Phra Klang) in the Thonburi period wrote to a Danish official in Trankabar, a southern Indian trading port, requesting assistance for Captain Lek (Francis Light) to procure 10,000 flintlock muskets there.

In recognition of Captain Francis Light’s valuable assistance in acquiring firearms for the kingdom to fight enemies, King Taksin bestowed upon him the noble title Phraya Ratchakapitan around 1778 (B.E. 2321).

During the reign of King Taksin of Thonburi, Thailand enjoyed amicable relations with Great Britain. Historical records indicate that King Taksin once commissioned Chao Phraya Phra Khlang to send a royal letter to the Governor of Madras, then a British colonial administrative center in India. In response, Mr. George Stratton, the Governor of Madras at the time, sent a letter dated July 18, 1777 (B.E. 2320) to King Taksin. Along with the letter, he presented the King with a golden sword adorned with gemstones as a token of goodwill. At the end of the letter, Stratton also respectfully requested permission for Francis Light to conduct trade freely within Thailand. This marked an early phase of positive Anglo-Siamese relations during the Thonburi period. Later on, Francis Light, the British trader mentioned above, worked diligently to secure Penang Island (then referred to as Ko Mak) for the British East India Company, to which he was affiliated. The goal was to establish it as a naval and trading outpost on the outer sea route (the Indian Ocean) to compete with the Dutch, who had already fortified themselves in Malacca. Light used his diplomatic skills and perseverance in negotiations with the Governor of Kedah (Phaya Saiburi), who at the time governed Penang. Notably, Kedah was a vassal state of Siam during this period—meaning Penang was technically under Thai suzerainty.

Dutch Junk (Ship)

(Image from the book Boats: The Culture of the Chao Phraya River Basin People)

Phraya Saiburi was worried that the Thai army would march down to attack Saiburi (because at that time, the Thai army was driving out the Burmese in the southern border towns during the Nine Armies War). As a result, he agreed to allow the British to lease Penang Island in the year 1786 (B.E. 2329), which was the fifth year of the reign of King Buddha Yodfa Chulaloke the Great (Rama I).

Francis Light was then appointed as the first governor of Penang Island (formerly called Ko Mak). He renamed it “Prince of Wales Island” in honor of the Prince of Wales of England.

14.2.3 Trade Relations with the Dutch

In the year 1770 (B.E. 2313), merchants from Terengganu and from Jakarta (then called Yakkatra, the capital of Java, present-day Indonesia) brought 2,200 flintlock muskets as tribute to King Taksin while he was preparing to lead his army to suppress the rebellion of the Phang chieftains. This indicates that the Dutch were another European nation trading with Siam during the Thonburi period, as the Dutch held control over Java at that time.

Muskets or long guns of the matchlock type

(Image from the book Thai Military History in the Reign of King Chulalongkorn)

14.2.4 Relations with France

When King Taksin successfully established Thonburi as the capital, Father Corre, who was originally the teacher of Gallach General and had escaped from the Burmese roundup, came to pay homage with about 400 surviving Catholics. They were granted land to build the Santa Cruz Church on September 14, 1769 (B.E. 2312). Some Catholics were selected to serve in the government and cooperated well until the end of Father Corre’s life.

In 1773 (B.E. 2316), Father Joseph Louis Coude was sent from Paris to replace him. Toward the end of King Taksin’s reign, conflicts arose between the king and Father Coude, leading to the king’s displeasure and the exile of Father Coude to Phuket until the end of the reign.

It can be said that there is no evidence of trade relations with France during this period, except for religious ties.