King Taksin The Great

Chapter 10: King Taksin’s Royal Duties in the Military Sphere

King Taksin the Great undertook military affairs with a firm royal resolve, setting forth three principal objectives:

Suppressing the various factions within the country that had arisen following the fall of Ayutthaya to the Burmese. Many major provinces had declared themselves independent powers, and it was essential to subdue them in order to reunify the kingdom under a single sovereignty.

Defending the kingdom, anticipating inevitable warfare, as foreign enemies had not yet been fully vanquished. Vigilance and readiness were required to safeguard the nation’s sovereignty.

Expanding royal influence, by extending the realm and power of Siam throughout the Indochinese Peninsula, aiming to establish broader and more secure dominion.

These objectives reveal King Taksin’s vision not only to restore independence, but also to build a unified and powerful Siam.

10.1 Which factions did King Taksin suppress?

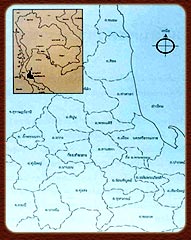

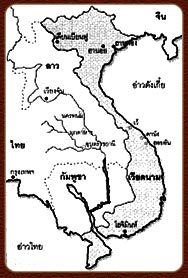

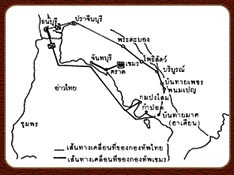

Map Showing the Locations of Influential Factions in the Early Thonburi Period

(From the book “สาระน่ารู้กรุงธนบุรี” or “Essential Knowledge of Thonburi”)

The suppression of the four factions to reunify the nation

In order to reunite the Kingdom of Siam into a unified realm, it was necessary for King Taksin to suppress various independent factions that had emerged following the fall of Ayutthaya. Although His Majesty was at a disadvantage—not having a native stronghold of his own (at that time his base was in Chanthaburi) and lacking noble rank or widespread recognition like other local warlords—he held a distinct advantage: he was in the prime of his life, full of energy, sharp in mind and spirit, and decisive in action.

10.1.1 What was King Taksin’s strategy in unifying the various factions?

At first, King Taksin of Thonburi intended to use force to attack the strongest factions first, believing that if he could defeat the most powerful groups, the weaker ones would be intimidated and willingly submit to his authority without further conflict. However, events did not unfold as he had anticipated.

Consequently, His Majesty adjusted his royal policy—reversing the approach to first consolidate the weaker factions under his control. This allowed him to strengthen his own forces, after which he turned his attention back to conquering the stronger factions, now with greater military power and support.

Steps in the Unification Campaign by King Taksin the Great

Step 1: The Campaign Against the Group of Chao Phraya Phitsanulok (Rueang), 1768 (B.E. 2311)

King Taksin of Thonburi led an army to subdue the powerful group under Chao Phraya Phitsanulok. Upon reaching Koei Chai (present-day Nakhon Sawan), his forces clashed with those of Phitsanulok. During the battle, King Taksin was wounded by a bullet to his left shin, forcing a royal order to retreat.

Afterward, Chao Phraya Phitsanulok declared himself king, but reigned only briefly — around 7 days — before succumbing to a throat abscess and passing away.

His younger brother, Phra Inthorakorn, took over the city but was soon overthrown by an army from Chao Phra Fang, who executed him in Phitsanulok.

(Source: Prasert Na Nakhon, 1991; “สาระน่ารู้กรุงธนบุรี”, 2000)

Step 2: The Campaign Against the Faction of Chao Phimai, 1768 (B.E. 2311)

With Thonburi established as the capital, King Taksin turned to suppress the Chao Phimai faction. He led his troops to attack Nakhon Ratchasima and won a decisive victory.

Upon hearing of this, Chao Phimai (Prince Thepphiphit) fled with his family and followers, intending to seek refuge in the Kingdom of Lan Xang (Laos).

However, Khun Chana, a city official of Nakhon Ratchasima, captured him and presented him to King Taksin. Chao Phimai was subsequently executed.

Khun Chana was rewarded for his loyalty and valor with the title Phraya Kamhaeng Songkhram, and was appointed as the new governor of Nakhon Ratchasima.

(Source: “สาระน่ารู้กรุงธนบุรี”, 2000)

Step 3: The Campaign Against the Nakhon Si Thammarat Faction, 1769 (B.E. 2312)

King Taksin of Thonburi launched a combined land and naval expedition to subdue the faction under the ruler of Nakhon Si Thammarat. Seeing that he could not withstand the royal forces, the ruler fled with his family and followers to Pattani, but was captured by the governor there and handed over to Chao Nara Suriyawong, the newly appointed ruler of Nakhon Si Thammarat.

King Taksin later summoned the deposed ruler to Thonburi to determine his punishment. However, upon arrival, the king granted him royal pardon, accepted his service as a government official, and granted him land to reside on. The former ruler also offered his daughter, Chim, to serve as one of the king’s consorts.

By the end of 1776 (B.E. 2319), Chao Nara Suriyawong passed away, and King Taksin reappointed Chao Nu (the former ruler) to govern Nakhon Si Thammarat once more, this time with the rank of a vassal king, styled Phra Chao Nakhon Si Thammarat.

Note: In 1785 (B.E. 2328), during the reign of King Rama I, Chao Nu was accused of multiple offenses by his son-in-law, Chao Phat, and was summoned to the capital for trial. Chao Nu lost the case and requested to remain in government service in Bangkok, where he passed away about a year later. Chao Phat was then appointed Chao Phraya Nakhon Si Thammarat in his place.

(Source: “สาระน่ารู้กรุงธนบุรี”, 2000: 138-139)

Step 4: The Campaign Against the Phra Fang Faction

After the fall of Ayutthaya to Burma, Maha Rueang, a monk, gathered followers and established authority in several cities. He declared himself ruler despite not having disrobed, changing only his robes to red. He became known as Chao Phra Fang and led a powerful faction in the north.

In 1768 (B.E. 2311), upon learning of the death of Chao Phraya Phitsanulok and the succession of Phra Inthorakorn, Chao Phra Fang marched to capture Phitsanulok. With support from locals who opposed the new ruler, he succeeded and ordered Phra Inthorakorn’s execution, confiscating wealth, weapons, and relocating the population to Fang.

By 1770 (B.E. 2313), Chao Phra Fang’s rule grew increasingly corrupt and immoral, as he drank alcohol, committed acts against monastic codes, and sent rogue monk-commanders to raid villages. Upon hearing of this, King Taksin ordered a campaign to subdue him. The battle lasted three days, after which Chao Phra Fang fled with his followers and a rare white elephant calf. Thonburi’s forces captured the elephant, but Chao Phra Fang disappeared without a trace.

(Source: “สาระน่ารู้กรุงธนบุรี”, 2000: 139-140)

Rajawongse Sumanachat Sawatdikun remarked on the great wisdom and capability of King Taksin the Great in subduing the various factions during the early Thonburi period in his work “King of Thonburi”, published in “Mahawitthayalai” Journal, Vol. 15, No. 2, B.E. 2480 (1937):

“King Taksin’s brilliance in fully liberating Ayutthaya from foreign control is profoundly praiseworthy.

If one compares his position with that of other powerful contemporaries, it is evident that he had the least advantage in the quest to restore the kingdom.

Chao Phraya Phitsanulok had a stable base and a strong army.

Chao Phra Fang was highly favored by the people, who believed he possessed magical powers.

The ruler of Nakhon Si Thammarat had both manpower and martial prowess—capable of maintaining independence without any external help.

Chao Phimai held royal blood and was beloved by the people, who admired his merit and supernatural qualities.

Phraya Nai Kong (called Suki by the Burmese, a title meaning commander, later used as a name in Thai sources) and Chao Thong-In or Nai Boonsong, as recorded in the chronicles, also had Burmese military support.

King Taksin alone stood with the least resources. He had only 500 soldiers, a single firearm, and no permanent shelter—wandering across regions with hardship and struggle.

Even his decision to establish a base in Chanthaburi was not originally part of a grand strategy but rather a necessity forced by circumstance.

His situation stood in stark contrast to others. He relied solely on his own courage, intellect, youthful vigor, and exceptional leadership skills.”

Major General Luang Wichitwathakan also discussed King Taksin’s military campaigns to suppress the four major factions—Phitsanulok, Fang, Nakhon Si Thammarat, and Phimai—in his work “Siam and Suvarnabhumi” (cited in Thai Journal, Vol. 20, Issue 72, Oct–Dec B.E. 2542):

“He subdued each faction one by one, aided by two great heroes: King Rama I (Somdet Phra Phutthayotfa Chulalok) and Krom Phra Ratchawang Bowon (Chao Phraya Surasi).

Within only three years, all factions were defeated, and the Kingdom of Siam was once again united in B.E. 2313 (1770), restoring strength and unity to the realm.”

10.2 What royal duties did King Taksin perform to defend the kingdom?

To defend the kingdom, King Taksin’s royal duties included waging war against the Burmese and eliminating Burmese influence from the Lan Na region.

10.2.1 War with Burma

After reclaiming Ayutthaya, King Taksin’s foremost and most critical task was defending the kingdom from Burmese threats. Following his victory at the Battle of Pho Sam Ton camp in November 1767 (B.E. 2310), Thailand fought the Burmese nine more times during King Taksin’s reign. Details are as follows:

The First War: Battle of Bang Kung | Year Pig (1767, B.E. 2310)

After King Taksin recaptured Ayutthaya from the enemy (breaking the Pho Sam Ton camp and killing the Burmese leader Suki Phra Nay Kong in that battle), his fame spread widely. His glory as the savior of Thailand from Burma was renowned. King Taksin established his seat in Thonburi and held a coronation ceremony in the Year of the Pig, 2310 B.E. The major and minor towns gladly accepted him, with many people pledging allegiance, including foreign traders such as the Chinese, who recognized him as the Thai king.

Following his coronation and proclamation as the Great King of Ayutthaya according to ancient royal traditions, King Taksin rewarded his commanders and officials. Notably, Nai Sutjinda was appointed Minister of Police, and Luang Yokkrabat from Ratchaburi (the elder brother of King Rama I of the Chakri dynasty) was also invited to serve, becoming the royal official in charge of police duties.

When it comes to the governance of the provinces, the Royal Chronicles state that after King Taksin was crowned, he appointed officials to oversee all the small and large cities. However, according to the records, there were only a few cities at that time with enough population to be quickly reestablished as proper cities. Roughly, the provinces were:

Northern Cities: Ayutthaya (the old capital), Lopburi, Ang Thong

Eastern Cities: Chachoengsao, Chonburi, Rayong, Chanthaburi, Trat

Western Cities: Nakhon Chai Si, Samut Songkhram, Phetchaburi

This totals about 11 cities that still had enough people to be reestablished, and it was necessary to appoint governors as before.

King Taksin assigned troops to be stationed across these cities. Chronicles mention sending Chinese soldiers to set up a camp in Bang Kung, in the Samut Songkhram area bordering Ratchaburi. It is believed similar garrisons existed elsewhere, though not specifically recorded.

After King Taksin recaptured Ayutthaya, the ruler of Vientiane (referred to as “Krung Si Sanakanhut”), who sided with Burma at the time, reported to the King of Ava that Taksin had taken power and restored Ayutthaya as the capital. The King of Ava was worried about a war with China and doubted the situation in Siam would be significant since the country was devastated and the population low.

Thus, the Burmese sent a royal order to Mangyi Marhya, the governor of Tavoy, to lead forces into Siam to suppress any uprising. Tavoy’s troops advanced via Sai Yok during the dry season, late Year of the Pig (B.E. 2310).

At that time, Kanchanaburi and Ratchaburi, located on the Burmese invasion route, were deserted. Burmese warships were stationed at Sai Yok, and Burmese forts lined the riversides at Ratchaburi but had not been dismantled.

When the Tavoy forces arrived at Bang Kung and saw King Taksin’s Chinese troops camped there, they laid siege. King Taksin assigned Phraya Mahamontri to command the vanguard, while he himself led the main army to Samut Songkhram to attack the enemy.

Phraya Tavoy, seeing he was losing, retreated back to Tavoy. At the checkpoint at Chao Khwao (near Ratchaburi on the Pashee River), the Thai army captured all Burmese warships, weapons, and supplies.

The Second War: When the Burmese attacked Sawankhalok | Year of the Tiger, B.E. 2313

This war occurred when King Taksin expanded his kingdom northward into Burmese territory. He had regained all former Ayutthaya territories within his realm except for Tanintharyi (Tenasserim) and Mergui, which were still under Burmese control, along with Cambodia and Malaya, which remained vassal states.

King Taksin stayed to govern the northern cities throughout the rainy season, persuading scattered villagers to return to their original homes and surveying the population of the northern cities as follows: Phitsanulok had 15,000 people, Sawankhalok 7,000, Phichai (including Sawangkhaburi) 9,000, Sukhothai 5,000, and Kamphaeng Phet and Nakhon Sawan each had just over 3,000.

He appointed officials honored for their service in the war: Phra Yommarat (Krom Phra Ratchawang Bowon Mahasurasinghanat) was appointed as Chaophraya Surasi Phitsanuwathirat to govern Phitsanulok; Phra Phichai Racha was made Chaophraya governing Sawankhalok; Phra Siha Ratcha Det Chai became Phra Phichai; Phra Thainam was appointed Phra Sukhothai; Phra Surabodin of Chainat became Phra Kamphaeng Phet; and Phra Anurak Phuthon was made Phra Nakhon Sawan. He also appointed Phra Aphaironnarit (later King Rama I of Rattanakosin) as Phra Yommarat and commander of the Ministry of Interior, replacing the prime minister who was dismissed for being weak in war.

After organizing the northern cities, King Taksin returned to Thonburi.

At that time, Burma ruled Chiang Mai. The King of Ava had appointed Aphai Kamni, who had risen to the rank of Pomayungwan, as ruler of Chiang Mai since the old kingdom. When the Thonburi army attacked Sawangkhaburi, some of the Chaophraya Phang forces fled to seek refuge with the Burmese in Chiang Mai. Pomayungwan saw an opportunity to expand his territory downward because the Thai of Sawangkhaburi sided with King Taksin.

Therefore, he led his army to attack Sawankhalok in the 3rd month of the Year of the Tiger, B.E. 2313. At that time, Chaophraya Phichai Racha had just moved to Sawankhalok less than three months before, and his forces were still small. However, Sawankhalok had an ancient and strong fortress, so Chaophraya Phichai Racha defended the city and requested help from nearby cities.

The Burmese army attacking Sawankhalok was led by the Chiang Mai commander and mostly consisted of local soldiers under Burmese control. Seeing the defenders’ resolve, they besieged the city.

When Chaophraya Surasi, Phra Phichai, and Phra Sukhothai brought reinforcements and attacked the Burmese from both sides, the Burmese forces were defeated and fled. During this battle, the Thonburi army itself was not seriously troubled.

The Third War: The First Thai Attack on Chiang Mai | Year of the Rabbit, B.E. 2314

The reason King Taksin led an attack on Chiang Mai at this time was likely due to his strategic thinking. The Burmese forces in Chiang Mai were not very strong or numerous. The Ava kingdom was also engaged in war with China and could not send reinforcements. Since Chiang Mai had recently broken away from Sawankhalok, their forces were fearful and unsettled.

King Taksin saw an opportunity to follow up immediately with an attack on Chiang Mai. Even if the city could not be captured, the campaign would still weaken the Burmese forces and provide valuable knowledge of the terrain for future plans.

With both the royal army and regional forces prepared, the campaign was launched at the beginning of the Year of the Rabbit, B.E. 2314.

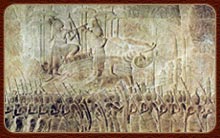

The image shows the ruins of forts and the inner city walls of Chiang Mai, which date back to the historical city layout. These remnants have been preserved to this day as part of cultural heritage conservation efforts.

(Source: Daily News Newspaper; www.chiangmaihandicrafts.com/…/wallandmoat.htm)

The royal army of King Taksin of Thonburi, in its campaign to capture Chiang Mai, first assembled its forces at Mueang Phichai, mustering a total of 15,000 men. Chao Phraya Surasi was appointed commander of the vanguard, while His Majesty personally led the main army. The march proceeded without hindrance until they reached Lamphun. Upon learning of the swift advance, Bo Mayung Nguan, the Burmese commander stationed at Chiang Mai, refrained from engaging in open-field combat. Instead, he ordered his forces to establish defensive encampments outside the city.

The vanguard under Chao Phraya Surasi successfully routed the Burmese field positions. Consequently, Bo Mayung Nguan withdrew his troops into the city, fortifying its ramparts. The Thonburi army laid siege and launched an assault by night, beginning at the third hour and continuing until dawn. Yet the walls held fast, and the attack failed. Recognizing the strength of Chiang Mai’s fortifications, King Taksin ordered a strategic withdrawal.

A popular saying held that no monarch could capture Chiang Mai on the first attempt—success came only on the second. Such belief may have influenced the king’s decision to fall back.

Seizing the opportunity, Bo Mayung Nguan launched a counteroffensive, sending his troops to harass the retreating Siamese. The Burmese vanguard engaged the Thai rearguard, causing disarray. Witnessing the threat firsthand, King Taksin descended to personally command the rearguard, drawing his sword and leading the charge. His soldiers rallied, engaging the Burmese in fierce hand-to-hand combat. Overwhelmed, the Burmese were driven back.

The king then returned to his royal barge at Phichai and sailed back down to the capital.

(For more details, see Section 10.2.2: The Eradication of Burmese Influence from Lan Na.)

The Fourth War: First Burmese Invasion of Phichai | Year of the Dragon, 2315 B.E.

The next two campaigns (Wars IV and V) were minor skirmishes, arising more from the pride of Burmese generals than from strategic intent. In 2314 B.E., a dispute broke out in the kingdom of Sri Sattanakhanahut between Prince Suriya Wong of Luang Prabang and Prince Bun San of Vientiane. Prince Suriya Wong launched an attack on Vientiane. Prince Bun San appealed to the King of Ava for aid.

The Burmese king dispatched Chikshingbo as the vanguard and Bo Suphla as commander of the main force to assist Vientiane. Learning of the invasion, Prince Suriya Wong retreated to defend Luang Prabang, the frontier city the Burmese would have to pass through.

Bo Suphla attacked Luang Prabang, and when the defenders failed to resist, the city capitulated. Bo Suphla was then ordered to remain in Chiang Mai to prepare for future Thai counteroffensives. He advanced through Nan Province, and nearing the Siamese border, may have wished to demonstrate his military prowess, particularly to Bo Mayung Nguan, who had once suffered defeat by the Thais at Sawankhalok.

Bo Suphla divided his forces and sent Chikshingbo to invade Siam. The Burmese took Lap Lae (modern-day Uttaradit) with ease, facing no resistance. Dissatisfied with their spoils, they marched further to attack Phichai during the dry season at the end of 2315 B.E.

At that time, Phichai’s garrison was small. Phraya Phichai fortified the city and refrained from open battle, sending for reinforcements from Phitsanulok. Chao Phraya Surasi quickly mobilized and marched to Phichai’s aid. Burmese forces had encamped at Wat Eka. Upon arrival, the Siamese troops launched a direct assault, while Phraya Phichai led a flanking maneuver, striking from another direction.

The clash escalated into hand-to-hand combat, and unable to hold their position, the Burmese were routed, fleeing northward to Chiang Mai.

This particular war is not recorded in Burmese chronicles, but according to the Royal Siamese Annals, Bo Suphla personally led the campaign. However, Prince Damrong Rajanubhab, having examined the ease of the Burmese defeat, concluded that it could not have been a major invasion. He reasoned that Bo Suphla must have only sent a subordinate commander, and upon learning of the defeat, would later lead a larger force himself—a matter discussed in the following section.

The Fifth War: Second Burmese Invasion of Phichai | Year of the Snake, 2316 B.E.

In early 2316 B.E., internal conflict erupted once again in Vientiane. One faction sought assistance from Bo Suphla, who led a force to suppress the unrest and remained in Vientiane through the rainy season. Growing suspicious of Prince Bun San, Bo Suphla forced him to send his children and top ministers to Ava as hostages.

At the end of the rainy season, Bo Suphla returned from Vientiane and proceeded to launch another attack on Phichai.

This assault may have stemmed from two primary motivations:

Reason 1, Bo Suphla may have received reports from Ava that King Mangra was planning a major campaign against Thonburi. Bo Suphla, wishing to test the mettle of the Thai forces, believed his own army, hardened by campaigns such as the capture of Luang Prabang, would prevail easily against the defenders of Phichai.

Reason 2 might also be that Pausupla felt deeply humiliated by the previous defeat of his troops, who had fled from Phichai in the Year of the Dragon (2315 BE), and thus resolved to return and redeem his honor in battle personally.

According to the Royal Chronicles, once the rainy season of 2316 BE ended, Pausupla once again led an army intending to attack Phichai. But this time, the Siamese were forewarned. Chaophraya Surasi and Phraya Phichai led forces to ambush the Burmese army at a strategic location along the route. When the Burmese arrived, the Siamese launched a sudden assault and routed Pausupla’s forces on Tuesday, the 7th waning day of the second lunar month, Year of the Snake, 2316 BE.

In this battle, during hand-to-hand combat, Phraya Phichai wielded twin swords, driving into enemy ranks until one of his swords broke. His bravery and skill earned lasting fame, and from that time onward, he became known as “Phraya Phichai of the Broken Sword.”

The Sixth war: The Second Siamese Expedition Against Chiang Mai | Year of the Horse, 2317 BE

King Taksin of Thonburi, while contemplating future military action, received reports of a major Mon rebellion against Burma. The rebellion was rapidly spreading, and it was judged that the Burmese would be preoccupied with subduing the Mon for a considerable time, and thus would be unable to turn their focus toward attacking Siam. This presented a strategic opportunity to strike Chiang Mai and weaken Burmese power in the region.

The King led the army north via Kamphaeng Phet and held a war council at Ban Rahaeng (now the site of modern-day Tak Province). News arrived that the King of Ava had appointed Alaungpaya Hsinbyushin (Asa Hkwan Kyi) as commander-in-chief to suppress the Mon uprising near Rangoon. The Mon forces were defeated and began to flee southward.

King Taksin then ordered Chao Phraya Chakri (later King Rama I) to lead the main northern army alongside Chao Phraya Surasi in a renewed assault on Chiang Mai, while the royal army remained stationed in Tak, awaiting further reports from Martaban.

The forces under Chao Phraya Chakri and Chao Phraya Surasi advanced through Lampang, and when Chao Phraya Chakri secured the city, King Taksin remained encamped at Ban Rahaeng. At that time, Mon refugees fleeing the Burmese began entering Siam through the Tak frontier, and Khun Inthakhiri, commander of the border post, escorted a Mon cook named Sming Suharai Klan to the King.

Upon interrogation, it was learned that the Mon had been defeated at Rangoon and that Alaungpaya was in pursuit. The Mon were now fleeing with their families en masse into Siamese territory.

Upon hearing that Phraya Kawila had led the people of Chiang Mai and Lampang to ally themselves with Siam, the King recognized this as a critical opportunity. He thus dispatched orders from Thonburi to Phraya Yommarat Khaek (son of Chao Phraya Chakri Khaek, who had previously passed away—Phraya Yommarat Khaek had earlier held the position of Phraya Ratchawangsan) to lead a force and set up a blockade at Tha Din Daeng, in preparation to receive incoming Mon refugees who would pass through the Three Pagodas Pass. Additionally, orders were given for Phraya Kamhaeng to support the effort.

Wichit commanded a force stationed at Ban Rahaeng, tasked with receiving Mon civilians who were fleeing into Siam through the Tak Pass. Later, the main royal army departed Ban Rahaeng on the 5th waning day of the first lunar month, Year of the Horse, B.E. 2317, and followed the route of Chao Phraya Chakri’s army toward Chiang Mai.

As for the army of Chao Phraya Chakri, having advanced from Nakhon Lampang, it reached Lamphun, where it encountered a Burmese force that had established a blocking encampment along the old Ping River, north of Lamphun. The Siamese launched an assault on the Burmese camp, resulting in several days of fierce fighting. When the main royal army arrived at Lamphun, Chao Phraya Chakri, Chao Phraya Surasi, and Chao Phraya Sawankhalok led a combined assault that broke the Burmese lines, forcing them to retreat to Chiang Mai. The royal army was then stationed in Lamphun, while Chao Phraya Chakri’s forces pursued the enemy and laid siege to Chiang Mai.

Within the city, Bo Suphla and Bo Mayung Nguan, the Burmese commanders, who had been tasked with the city’s defense, upon seeing the Siamese establishing encampments around the city, led their troops to set up counter-camps in proximity to the siege lines and launched several raids against the Thai positions. However, each time they were repelled by accurate Siamese gunfire, resulting in heavy Burmese casualties and forced withdrawals back to their camps.

At the same time, many inhabitants of Chiang Mai, who had taken refuge in the surrounding forests, began to emerge and join the Siamese army. Even residents within the city walls found means to flee and surrender to the Siamese in large numbers.

The Chang Phueak Gate was reconstructed between B.E. 2509–2512 (A.D. 1966–1969), while the Tha Phae Gate was rebuilt later, during B.E. 2528–2529 (A.D. 1985–1986). These restoration projects were undertaken by the Chiang Mai Municipality in collaboration with the Fine Arts Department, relying on historical and archaeological evidence, along with photographic documentation as primary references.

(Source: Seen: Architectural Forms of Northern Siam and Old Siamese Fortifications)

On Saturday, the 3rd waxing day of the second lunar month, King Taksin of Thonburi led the royal army from Lamphun and took up position at the main encampment along the riverbank, near Chiang Mai. He proceeded to inspect the siege works that encircled the city, desiring to hasten the assault so that Chiang Mai might be taken swiftly. That very day, Chao Phraya Chakri launched an attack on the Burmese encampments which had been deployed beyond the southern and western walls—he succeeded in breaking all of them. Meanwhile, Chao Phraya Surasi stormed the eastern front, targeting the Burmese camps near the Tha Phae Gate, capturing three positions.

That night, Bo Suphla and Bo Mayung Nguan, the Burmese commanders, realizing the city could no longer be held, fled Chiang Mai through the Chang Phueak Gate to the north, directly in the front of Chao Phraya Sawankhalok’s position. As the siege ring was not yet fully sealed, they managed to break through. The Siamese forces gave chase, recovered a significant number of civilian captives, and inflicted severe casualties upon the Burmese.

At dawn the next day—Sunday, the 4th waxing day of the second lunar month—King Taksin made a ceremonial entry into Chiang Mai with his royal procession. With the successful capture of the city, just two days later, word arrived from Tak that another Burmese army had crossed into Siamese territory in pursuit of Mon refugees.

King Taksin, therefore, delegated Chao Phraya Chakri to remain in Chiang Mai to restore order and governance, while the king himself, after staying seven days, led the royal army back to Tak.

Chao Phraya Chakri, now in command of Chiang Mai, dispatched officials and nobles throughout the region to persuade the local populace to return to their ancestral settlements. The people of Lan Na, being ethnically Thai and having lived under Burmese rule against their will, welcomed the restoration of Siamese sovereignty and submitted peacefully without the need for further conflict. On this occasion, Chao Phraya Chakri also won over the Prince of Nan, who pledged allegiance and became a tributary vassal once again.

Thus, Chiang Mai, Lamphun, Nakhon Lampang, Nan, and Phrae were successfully restored to the Kingdom of Siam during this campaign. (See details at 10.2.2)

The Seventh War: The Burmese Campaign at Bang Kaeo, Ratchaburi (Siamese Siege and Burmese Starvation) | Year of the Horse, 1177 B.E. (A.D. 1774)

Upon His Majesty King Taksin’s return to the capital from the victorious campaign in Chiang Mai, urgent news reached the court that a Burmese army had breached Siamese territory via the Three Pagodas Pass, attacking the army of Phraya Yommarat Khaek, which had been stationed at Tha Dindaeng. Defeated, the Siamese forces withdrew and regrouped at Pak Phraek, present-day Kanchanaburi.

At that time, the royal army that had followed His Majesty on the northern campaign was still en route by river and had yet to return in full. His Majesty immediately ordered a domestic levy of troops from the capital. Prince Chui, his son, and Phraya Thibetsabodi, the Chief Palace Steward, were each given command of 3,000 men and dispatched to fortify Ratchaburi. Chao Ram Lak, the king’s nephew, was sent to reinforce the campaign with an additional 1,000 troops. Orders were also given for the northern provincial armies to advance south, and a royal command was issued to hasten the return of the main army from the northern front.

According to Burmese chronicles, Azaewungyi (อะแซหวุ่นกี้) dispatched Ngui Okhong Wun (also known as Chap Phaya Kongbo or Chap Kungbo) to lead the current invasion. His mission was solely to retrieve Mon refugees who had fled into Siam. If successful in capturing them, he was to escort them back; if not, he was to withdraw peacefully. However, Ngui Okhong Wun, confident from previous victories over the Siamese, grew emboldened. After defeating Phraya Yommarat Khaek at Tha Dindaeng, he advanced to Pak Phraek. Facing no resistance, Phraya Yommarat Khaek abandoned the camp and fell back to Dong Rang Nong Khao.

Seeing no opposition, Ngui Okhong Wun divided his army into two columns. One, led by Mongchayik, was stationed at Pak Phraek to plunder the surrounding areas and capture civilians across Kanchanaburi, Suphanburi, and Nakhon Chai Si. The second column, under Ngui Okhong Wun himself, launched raids in Ratchaburi, Samut Songkhram, and Phetchaburi. Upon reaching Bang Kaeo, he learned of the Siamese presence at Ratchaburi and accordingly established three fortified camps there.

In Ratchaburi, Prince Chui, now apprised of the Burmese encampment at Bang Kaeo and believing the situation favorable, especially with reinforcements on the way, mobilized his army to Khok Kratai in the Thung Thammasen plains—about 80 sen (approx. 7.8 kilometers) from the Burmese position. There, he ordered:

Luang Maha Thep to lead the vanguard and encircle the Burmese from the west

Chao Ram Lak to establish a flanking position from the east

King Taksin of Thonburi ordered Phraya Phichai Aisawan to take charge of defending Nakhon Chai Si, while His Majesty personally led the royal army to Ratchaburi. Upon arrival, the King visited the encampment encircling the Burmese forces at Bang Kaeo, examined the terrain, and gave instructions for additional fortifications to be built, tightening the siege further.

Chao Phraya Intharaphai was tasked with guarding the reservoir at Khao Chua Phruean, a strategic source of water for the enemy’s elephants and horses, and a major supply route. Phraya Ramanwong was assigned to lead Mon troops to secure the reservoir at Khao Chaguem, situated along another northern supply line used by the Burmese, roughly 120 sen (11.7 km) from the encampment.

Nguiya Khong Hwon, the Burmese general under siege, observed the increasing pressure and launched a night raid against Chao Phraya Intharaphai’s encampment. The Burmese were repelled. That same night, they attempted three assaults, each of which ended in failure, with significant losses and numerous prisoners taken by the Siamese.

Realizing the might of the Siamese army, Nguiya Khong Hwon requested reinforcements from the Burmese base at Pak Phraek. Alaungpaya’s general, Azaewunkyi, who had been stationed at Martaban (Mottama), followed upon hearing of Nguiya Khong Hwon’s disappearance and arrived at Pak Phraek just as news of the siege reached him.

Meanwhile, Chao Phraya Chakri returned from the campaign in Chiang Mai and marched his forces south to join the battle. The siege wore on. The Burmese, now surrounded and starving, endured relentless bombardment by Siamese cannons. Burmese casualties mounted, and eventually their generals were forced to surrender and submit to King Taksin. By that time, Azaewunkyi had already retreated to Martaban.

Following the capture of the Burmese encampment at Bang Kaeo, King Taksin ordered Chao Phraya Chakri to march immediately to attack the Burmese position at Khao Chaguem. That very night, at midnight, the Burmese staged a “khaai wihan” maneuver—an infiltration tactic where soldiers silently advance inch by inch toward the enemy’s defenses before launching a surprise assault from close range on all fronts.

The Burmese aimed to break through and support their besieged allies at Bang Kaeo. In this raid, they set fire to Phra Mahasongkhram’s camp. Chao Phraya Chakri arrived in time to reinforce and successfully retake the encampment. The Burmese were forced to retreat.

That same night, the Burmese garrison at Khao Chaguem abandoned their position and fled northward. The Siamese pursued them, inflicting heavy casualties. The Burmese commanders who managed to escape made their way to Pak Phraek, where Takheng Morn Nong, upon learning that all Burmese forces had been defeated, chose not to resist and swiftly retreated to rejoin Azaewunkyi at Martaban.

King Taksin commanded his army to pursue the fleeing Burmese to the farthest reaches of the kingdom’s borders before ordering a return to the capital. In recognition of their valor and success, rewards and honors were bestowed upon the commanders, both senior and junior, who had distinguished themselves in the campaign.

The Battle of Bang Kaeo stands as a significant example of strategic defense outside the royal capital during the Thonburi era, embodying both offensive and defensive strategies. While its importance might seem modest at first glance, based on the interpretation of Somdet Krom Phraya Damrong Rajanubhab in Thai Combat Against Burma, this battle was essentially a prolonged engagement arising from the pursuit of Mon refugees who fled into Siamese territory under the command of Nguiya Khong Hwon.

Notably, the Burmese side—especially the supreme commander Alaungpaya (Azaewunkyi)—had no explicit intention to engage in sustained warfare with Siam, as they had yet to receive orders from King Mangra to invade Siam.

However, it is striking that evidence from both Thai and Burmese sources consistently confirms that the Burmese held a resolute determination to confront Siam directly. The clash was not merely a collateral result of pursuing Mon refugees, but represented a deliberate military confrontation.

A schematic map of the siege of the Burmese at Bang Kaeo, B.E. 2317 (1774)

(Image from the book King Taksin the Great)

The Royal Chronicle in the form of the Royal Letter describes this military campaign, stating that King Mangra ordered his officials to hasten the army of Azaewunkyi, then stationed at Mottama, to “pursue the Mon rebels and capture the Siamese cities.” Azaewunkyi thus organized both the vanguard and the supporting army, with the vanguard attacking the Siamese forces stationed at Tha Din Daeng.

Burmese sources, such as the accounts of the Ava people, note: “In the year 1136 of the Burmese era, Azaewunkyi led the army to attack Ayutthaya. The vanguard reached Ratchaburi, where the Siamese army laid siege.” Meanwhile, the Ho Kaeo Chronicle and the Konbaung Dynasty Chronicle clearly state that King Mangra commanded Azaewunkyi to invade Siam with decisive victory.

Therefore, the Battle of Bang Kaeo should be regarded as a major battle—not merely an encounter aimed at capturing Burmese troops pursuing Mon refugees and looting at will.

Thai and Burmese evidence consistently agree that the main objective of the Burmese commanders in the Battle of Bang Kaeo was to seize Ratchaburi. Consequently, Ratchaburi was a crucial strategic location in this war. However, this does not imply that Ratchaburi’s military strategic importance emerged only at this battle. Its significance dates back to the time of the Alawngpaya campaign (B.E. 2303), which followed the altered invasion route through Tavoy, compelling the Burmese army to advance through Phetchaburi, Ratchaburi, and Suphanburi.

This change made Ratchaburi an inevitable strategic gateway city.

More importantly, Thai and Burmese military strategists regarded Ratchaburi as the “final fortress” that an invading army would have to overcome to penetrate the heart of Siamese power. Historical records show that Ratchaburi had served as a strategic defensive city since the Alawngpaya campaign. During the 1767 fall of Ayutthaya, the main Thai forces intercepted the Burmese invasion under Mang Ma Noratha at Ratchaburi.

When the Burmese captured Ratchaburi, they used it as a base to divide their forces to attack Ayutthaya by two routes: one to block western cities such as Kanchanaburi and Suphanburi, and the other to block southern cities near Ayutthaya, including Thonburi and Nonthaburi.

Ratchaburi’s military strategic importance increased further during the Thonburi period, despite the Burmese shifting their invasion route to the Phra Chedi Sam Ong checkpoint.

The rise in strategic value resulted from internal changes within Siam. R.S. Sarisak Vallibhotama observed that with the capital moving south from Ayutthaya to Thonburi and later Bangkok, the invasion routes had to shift. To attack Bangkok or Thonburi, invading forces no longer needed to move through Kanchanaburi, Phanom Thuan, Suphanburi, and Ang Thong, but could instead move through Kanchanaburi, Ratchaburi, Nakhon Pathom, and Thonburi directly.

The new routes allowed movement by both land and water, especially along the Khlong Noi river to Pak Praek and then down the Mae Klong river to Ratchaburi.

Thus, the defense strategy during the Thonburi era evolved from the late Ayutthaya period. Victory or defeat no longer hinged on battles at the capital but on controlling key strategic towns.

In the Battle of Bang Kaeo, the decisive factor for victory or defeat was control over Ratchaburi by the commanding generals of both sides. It was therefore unsurprising that King Taksin acted swiftly and decisively to seize Ratchaburi as his military base.

The chronicles state that upon learning of the Burmese army’s approach via the Phra Chedi Sam Ong checkpoint, King Taksin commanded “Prince Chui and Phraya Thibethbodi, each leading 3,000 troops, to establish camps to defend Ratchaburi,” and also ordered Chao Ram Lak, his nephew, to lead 1,000 troops as reinforcement.

One division of the army, while the main force was following the King to attack Chiang Mai and in the process of sailing back to Thonburi, was ordered to have police boats board and escort them down. The King commanded, “Do not let anyone stop at any house under any circumstances. Anyone who does will be put to death.” When the royal boat carrying Phraya Phra Luang Khun Muen and all officials hastened to the palace dock, after respectfully paying their respects and bidding farewell, they were waved onward to hasten to Ratchaburi.

It is evident that this military campaign was urgent and time-critical. Anyone who disobeyed the royal command and caused delay would face severe punishment. Records show that when Phra Thep Yot stopped his boat to step ashore, upon learning this the King himself decreed capital punishment by beheading with his own hand. The head was then ordered to be displayed publicly at the front of Wichai Prasit Fortress as a warning, and the body was discarded in the water to prevent any imitation.

The army deployed for this campaign included a Mon contingent under Phraya Ramanyawong, as well as the forces of Chaophraya Chakri and the northern and eastern provincial armies, who joined subsequently. King Taksin himself led the main force of 8,800 men directly to the fortified camp at Ratchaburi.

Opposing them, Azaewunkyi, a highly skilled Burmese general, understood the strategic necessity of seizing Ratchaburi as a stronghold before the main Thai forces could take it. The defeat of Azaewunkyi’s army at Bang Kaeo was partly due to his failure to capture Ratchaburi. The vanguard he sent was pinned down by the Thai forces, preventing the main army gathered at Mottama from reinforcing them effectively.

Although the route through the Phra Chedi Sam Ong checkpoint chosen by Azaewunkyi for the Bang Kaeo campaign was a shortcut to quickly attack Thonburi, it was a rugged and difficult path. Moreover, any delay risking the enemy’s occupation of key terrain to block the route and cut off supplies would create serious difficulties for the Burmese army, especially the main army with its large forces requiring wide terrain for camp and maneuver.

Evidence from the Burmese side reveals the efforts of Azaewunkyi to swiftly launch an attack on the Thai forces. However, internal divisions arose within the army, causing delays. In brief, initially Azaewunkyi ordered the great commander Minye Zeya Kyaw, who led 3,000 royal guards, to strike and break through the Thai forces blocking the Burmese advance. Yet Minye Zeya Kyaw refused to carry out the order, claiming insufficient troops. Azaewunkyi reported this to King Mangra. Upon learning the situation, Minye Zeya Kyaw withdrew his forces to Mottama.

Consequently, Azaewunkyi had to dispatch Chap Phaya Kongbo (also called Nguy Okong Hun in Thai Fight Burma) to act instead, but this was too late. By the time the Burmese vanguard reached Pak Praek and Ban Bang Kaeo, the Thai army had already established a stronghold at Ratchaburi.

Azaewunkyi’s failure in the Battle of Bang Kaeo forced him to change his military strategy, shifting the campaign northward to attack Phitsanulok, as King Bayinnaung and Nemyo Sithu had done before. Strategically, the Battle of Bang Kaeo is thus a continuation of Azaewunkyi’s campaign. It was not only the largest and most important battle in King Taksin’s reign but also a battle that challenged and ultimately overcame the Thai defensive strategy—one adapted from hard-earned lessons since the 1767 fall of Ayutthaya.

The Thonburi to early Rattanakosin era was marked by strategic provincial towns becoming decisive battlefields. Ratchaburi was one such key town. The Battle of Bang Kaeo was essentially a battle for the strategic city of Ratchaburi, just as the Battle of Azaewunkyi was fought over Phitsanulok.

Victory or defeat here meant more than the loss of a strategic town—it could ultimately lead to losing the entire war and even the capital itself.

(Sunet Chutintharanon, 2000: 173–178)

Sri Chonlai (pen name) in 1939, in Thai Must Remember, wrote to glorify King Taksin the Great, stating

King Taksin the Great was not only the foremost of Thai warriors, but He also strove to show the world that Thailand was a nation of warriors upheld by the highest moral virtue. This was evident when the Burmese army invaded through Kanchanaburi, Ratchaburi, and Nakhon Chai Si in the Year of the Horse 2317 BE (the 7th year of the Thonburi era). At that time, King Taksin had just returned from subjugating Chiang Mai, and His Majesty’s mother was seriously ill. Yet, King Taksin resolutely set forth promptly to confront the Burmese at Ratchaburi, unwilling to allow the enemy to trample the outskirts of the capital, thereby dishonoring the Thai nation, nor did He wish the morale of the Thai people to falter.

After only nine days, Khun Wiset Oso hastened to report the grave condition of the Queen Mother. Upon hearing this, King Taksin uttered with deep sorrow that, “Her illness is so severe, I shall not live to see Her again. This land is in great peril. Now, there is no one trustworthy enough to stay and resist the enemy.” In the end, His Majesty broke His heart and did not return home, for His concern was for the realm. He persevered in battling the Burmese forces. Meanwhile, the Queen Mother passed away.

King Taksin continued the siege against the Burmese army, encircling them with no route for escape. Although His soldiers could have launched a mass volley to annihilate the enemy camp, He forbade it, preserving the honor of Thai warriors. When the enemy was utterly defeated and without means of resistance, Thai warriors refrained from unnecessary harm.

Eventually, the Burmese forces were exhausted and submitted to His Majesty’s sovereignty on March 31 of that year. Therefore, March 31 should be held as a solemn remembrance for Thai soldiers, who embodied the highest moral virtues, marking a proud legacy:

Thai soldiers hold the nation above all else, willing to sacrifice personal ties—even amid profound sorrow—so long as the nation’s cause is fulfilled.

Thailand does not invade others; yet if any nation dares trespass, Thai warriors will leave no enemy unvanquished.

Even when foes are trapped and defenseless, Thai warriors choose not to harm those who cannot resist, thus preserving honor.

Once the enemy yields, Thailand shows compassion and care appropriate to the circumstances, refraining from further vengeance.

Every inch of Thai soil stands free and independent because Thai warriors remain strong and resolute.

(Praphat Treenarong, Thai Journal 20(72), October–December 1999: 18–19)

The Eighth War: The Campaign of Aza Wungyi against the Northern Cities | Year of the Goat, 2318 BE

This war was a grander battle than any other during the Thonburi period. In this campaign, Aza Wungyi declared to his commanders that the Thai people were no longer as they had been in times past, meaning that from now on the Burmese would no longer be able to defeat the Thais.

The cause of this war arose when King Taksin the Great restored the independence of Siam, at a time when Burma was engaged in war with China. Upon completion of the Chinese campaign in the Year of the Rabbit, 2314 BE, the King of Ava conceived plans to invade Siam again. He intended to appoint Posupala as the general to lead the forces down from Chiang Mai, and Pakhan Wun as the general to advance through the Three Pagodas Pass, to besiege and attack Thonburi as had been done in the campaign against Ayutthaya.

However, both invasion routes were obstructed. From the north, the Siamese forces had already marched to capture Chiang Mai first; from the south near Martaban, while preparations were underway for the army’s advance, the Mon people rebelled fiercely, causing great turmoil. Therefore, the plan to invade Siam did not succeed as intended by the King of Ava.

Shwedagon Pagoda, Rangoon City

(Image from www.trekkingthai.com/cgi-bin/webboard/generat…)

In the Year of the Horse, 2317 BE, the King of Ava proceeded to raise the royal umbrella atop the sacred hair relic stupa, Shwedagon Pagoda, in the city of Rangoon. At that time, Aza Wungyi had already quelled the Mon rebellion, but was still awaiting the arrival of the Burmese army pursuing the Mon fugitives at Martaban. The King of Ava, seeing the large army stationed at Martaban, commanded that the plan to attack Chiang Mai be further devised by Aza Wungyi.

Aza Wungyi returned to Martaban in the fifth month of the Year of the Goat, 2318 BE. When the army of Taklang Mornong fled from the Thais back to Martaban, he reported the defeat of the Burmese forces by the Thais, who had captured the army of Nguy Ok Wun and crushed another Burmese force at Khao Changum. Thus, Taklang Mornong was forced to retreat once again.

อะแซหวุ่นกี้คิดแผนการตีไทยตามแบบอย่างครั้งพระเจ้าหงสาวดีบุเรงนอง คือจะยกกองทัพใหญ่เข้ามาตีหัวเมืองเหนือตัดกำลังไทยเสียชั้นหนึ่งก่อน แล้วเอาหัวเมืองเหนือเป็นที่มั่น ทั้งยกกองทัพบก ทัพเรือลงมาตีกรุงธนบุรีทางลำน้ำเจ้าพระยาทางเดียวดังนี้ จึงให้พักบำรุง

The troops were stationed at Mottama. Orders were sent to Poseuphla and Pomayuangwan, who had retreated from the Thai forces and were stationed at Chiang Saen, to return and capture Chiang Mai during the rainy season. They were also instructed to prepare warships, transport vessels, and gather provisions to supply the army of Acha Wunkyi, who would advance at the start of the dry season. Thus, Poseuphla and Pomayuangwan assembled their forces and marched down to attack Chiang Mai in the tenth lunar month of the year Ma-Me, 2318 BE.

Since the victory at Bang Kaeo, the Thonburi forces had a respite of five to ten months. Upon receiving news that Poseuphla and Pomayuangwan intended to attack Chiang Mai, King Taksin issued orders for Chaophraya Surasi to lead the northern city armies to aid Chiang Mai, and for Chaophraya Chakri to command the reinforcing army. The king commanded that if the Burmese were driven out of Chiang Mai, the armies were to pursue them and capture Chiang Saen.

Poseuphla and Pomayuangwan led the Burmese army to attack Chiang Mai ahead of the Thai forces, setting up camps close to the city to prepare the assault. However, their assembled forces were not very strong. When news came that the Thai army was approaching, the Burmese retreated back to Chiang Saen, avoiding battle.

Acha Wunkyi had prepared his army, and in the eleventh lunar month he sent Kalabo and Mang Yayangu, his younger brother, to lead the vanguard from Mottama. Acha Wunkyi himself followed with the main army. The Burmese troops entered through the Mae Lamao pass into Tak, then proceeded to Dan Lan Hoi, reaching Sukhothai. The vanguard camped at Kong Thani village by the New Yom River, while the main army rested at Sukhothai.

Meanwhile, Chaophraya Chakri and Chaophraya Surasi, stationed at Chiang Mai, were preparing to advance against Chiang Saen. Upon learning of the large Burmese army moving through Mae Lamao pass, they hastily withdrew their forces back toward the city.

At Sawankhalok and Mueang Phichai, upon arriving at Phitsanulok, the two Chaophrayas consulted on how to confront the enemy. Chaophraya Chakri observed that the Burmese had brought a large army, and the Thai forces in the north were far fewer. He advised to hold defense at Phitsanulok and await reinforcements from Thonburi. However, Chaophraya Surasi wished to strike the Burmese first, so he gathered the northern city armies and marched to engage the Burmese at Ban Kong Thani. Chaophraya Surasi advanced to camp at Ban Krai Pa Faek. The Burmese attacked and defeated the army of Phraya Sukhothai, who then retreated. They pursued and reached Chaophraya Surasi’s camp, fighting fiercely for three days. Seeing the Burmese greatly outnumbered them, he withdrew back to Phitsanulok.

Acha Wunkyi divided his Burmese forces to hold Sukhothai and personally led troops to besiege Phitsanulok, setting camps around the city on both sides of the river. Both Chaophrayas skillfully defended the city. While Acha Wunkyi was besieging Phitsanulok, the Thonburi army arrived, but Acha Wunkyi continued daily reconnaissance, inspecting strategic positions around the camp.

When Thonburi learned that Acha Wunkyi led a large army from the northern cities, at the same time a report came from the southern cities that Burmese forces were advancing from Tanintharyi in the south, King Taksin, wary of the threat, ordered a military levy to defend Phetchaburi and guard against Burmese forces expected to advance via Singkhon Pass. After organizing defenses in the southwest against the southern threat, King Taksin personally led the royal army of about 12,000 troops, departing the capital on Tuesday, the 11th waning day of the second lunar month of the year Ma-Mae, to confront the northern enemy forces.

First Phase of the Campaign

When King Taksin reached Nakhon Sawan, he first arranged communications to ensure easy coordination between the royal army and Chaophraya Chakri’s forces stationed at Phitsanulok. He ordered Phraya Racha Setthi to command the Chinese troops stationed at Nakhon Sawan to guard the supply routes and watch for enemies advancing down the Ping River. King Taksin then advanced the royal army along the Kwai Yai River to Pak Ping, within the jurisdiction of Phitsanulok, and set up the royal camp there. This location, at the canal junction, served as a shortcut for river travel between the Kwai Yai River at Phitsanulok and the Yom River at Sukhothai, located about a day’s travel downstream.

He commanded his commanders and generals to establish camps on both sides of the river at intervals from the royal army’s camp up to Phitsanulok city.

Phase 1: Camped at Bang Sai, commanded by Phraya Ratcha Suphawadi

Phase 2: Camped at Tha Rong, commanded by Chaophraya Intharaphai

Phase 3: Camped at Ban Kradad, commanded by Phraya Ratcha Phakdi

Phase 4: Camped at Wat Chulamani, commanded by Muen Samoechai Ratcha

Phase 5: Camped at Wat Chan Tai, Mueang Phitsanulok, commanded by Phraya Nakhon Sawan

Assign patrol units to guard all communication routes in every phase. Also prepare conscripted artillery troops as the vanguard, ready to assist any camp swiftly. Assign Phraya Sri Krailat to command 500 men to clear and maintain a route along the riverbank from Pak Ping through the camps up to Phitsanulok.

When the royal army advanced to link up with the forces guarding Phitsanulok, Acha Wunkyi promptly launched offensive attacks against the Thonburi army.

The chronicles record that after establishing camps along both banks of the river, Acha Wunkyi deployed three Burmese camps opposite Muen Samoechai Ratcha’s camp at Wat Chulamani on the western bank. Another Burmese force moved down to scout and confront Thai troops on the west side. Fighting occurred from the third camp down to the first camp at Bang Sai.

King Taksin dispatched 30 conscripted gunners with wagon-mounted artillery to assist Phraya Ratcha Suphawadi in defending the camps. The battles continued until nightfall, when the Burmese forces withdrew.

On Thursday, the 12th day of the waxing moon, third lunar month, King Taksin ordered Phra Thamtrilok, Phraya Rattanaphimon, and Phraya Chonburi to guard the royal camp at Pak Nam Ping. He then moved the royal army to establish at Bang Sai on the eastern bank to assist Phraya Ratcha Suphawadi.

That night, the Burmese attacked from the western bank, raiding Chaophraya Intharaphai’s camp at Tha Rong (the second camp). Fierce fighting ensued, but with 200 conscripted gunners dispatched by King Taksin, the Burmese failed to capture the camp and retreated.

At this time, Acha Wunkyi realized the Thai forces advancing from the south were stronger than expected. Fearing that dividing his forces from the siege of Phitsanulok might expose them to counterattacks from the two Chaophrayas in the north, he halted offensive operations against the Thonburi army.

Instead, he sent orders to 5,000 reinforcements at Sukhothai to detach and strike at the Thonburi army’s supply lines, deploying 3,000 troops for the operation. The remaining 2,000 soldiers were sent to reinforce the battle in Phitsanulok.

Second Phase of the Campaign

Upon seeing that the Burmese forces attacking the camps had withdrawn back toward Phitsanulok, King Taksin the Great prepared to strike the Burmese army besieging Phitsanulok. On Wednesday, the 13th day of the waxing moon, third lunar month, He commanded Phraya Ramanyawong to lead the Mon troops through Phitsanulok city to position close to the Burmese camps on the northern side.

Chaophraya Chakri and Chaophraya Surasi were ordered to increase their forces and set camps adjacent to the Burmese on the eastern side, while on the southern side, Phraya Nakhon Sawan, who was stationed at Wat Chan at the city’s rear, was assigned to extend wing-shaped camps to encircle the Burmese camps with several outposts.

The Burmese launched assaults on the Mon forces, but the Mon troops fired cannons causing heavy Burmese casualties and forced them to retreat to their camps. The Mon then established their camps firmly.

Meanwhile, Chaophraya Chakri and Chaophraya Surasi’s troops initially lost their camps to the Burmese, but Chaophraya Surasi led a counterattack, recapturing the camps and successfully driving the enemy back, establishing camps all around the Burmese positions.

When the Burmese counterattacked these camps, they were again defeated by the Thai forces. The Burmese then dug multiple trenches around their camps for protection as they continued assaults on the Thai camps.

The Thai forces responded by digging trenches that connected through the Burmese trenches, leading to fierce fighting in the trenches around each camp over several days. However, the Thai army was unable to break through the Burmese camps.

On Tuesday, the 2nd day of the waning moon, third lunar month, King Taksin arrived at the camp at Wat Chan at 10 p.m. He ordered all commanding officers encircling the Burmese to prepare for a coordinated attack. At 5 a.m., the signal was given for the Thai forces to launch a simultaneous, full-scale assault on the Burmese camps encircling the city’s eastern side.

The battle raged until dawn, but the Thai forces failed to penetrate the camps and had to withdraw.

Aware that the Thai had established close encirclement on the eastern side, Acha Wunkyi reinforced his troops there with his superior numbers and strengthened the defense.

Displeased at the failure to capture the camps, King Taksin convened a council of his commanders the next day at Wat Chan camp to deliberate the next strategy. It was agreed to change tactics:

Chaophraya Chakri and Chaophraya Surasi would combine their forces within the city and strike only at the southwestern Burmese camps.

Another division of the royal army would detach and maneuver to attack the Burmese from the rear, intending to encircle and break the enemy step by step.

Following this plan, King Taksin returned to establish the main royal camp at Tha Rong, the second defensive position below Pak Ping.

The Next Day, King Taksin the Great ordered the army of Phraya Nakhon Sawan, stationed at Wat Chan camp, to withdraw and join the royal army. He also commanded the forces of Phra Horathibodi and the Mon troops under Phraya Klang Mueang, who were at Bang Sai camp, to assemble and form a single army totaling 5,000 men.

He appointed Phraya Nakhon Sawan as the vanguard to advance and lie in ambush behind the Burmese camps on the western side. When the Burmese engaged in battle with Chaophraya Chakri’s forces, Phraya Nakhon Sawan was to launch a flanking attack.

King Taksin also ordered Phra Ratchasongkhram to bring additional artillery from the capital to support the campaign.

Meanwhile, the Burmese forces stationed at Sukhothai, following orders from Acha Wunkyi, divided their troops and marched toward Kamphaeng Phet. Their aim was to cut off Thai supply lines and then attack Phitsanulok as commanded.

The reconnaissance units of Phraya Sukhothai learned of the Burmese plan to advance on two fronts and reported it to King Taksin.

In response, King Taksin redeployed Phraya Ratchaphakdi and Phraya Phiphatkosat, who were stationed at Ban Kradat, to assist Phraya Rachasetthi in defending Nakhon Sawan.

He also ordered the Mon forces under Phraya Waeng to join Phra Luang Phakdi Songkhram’s army and quickly move to monitor the enemy at Ban Lan Dok Mai, Kamphaeng Phet district. Their mission was to discover which route the Burmese would take, to attack if favorable, or to retreat if overwhelmed.

Another army under Phraya Mahamontian was tasked with lying in ambush to flank the Burmese, supported by a separate unit led by Phraya Thammanun.

Chaophraya Chakri and Chaophraya Surasi led the main army to assault the Burmese camps encircling the city on the southwest side. They engaged the enemy, but the camps were not breached.

The supporting army intended to flank from another direction failed to arrive on schedule because Phraya Nakhon Sawan’s vanguard, part of Phraya Mahamontian’s forces, only advanced as far as Ban Som Poi, where they encountered Burmese troops and became engaged in combat, unable to advance further.

Thus, Chaophraya Chakri and Chaophraya Surasi had to hold their fortified camps.

What followed with Phraya Mahamontian’s forces remains unclear from the royal chronicles, but it is recorded that Phraya Nakhon Sawan’s troops returned to establish camp at Ban Kaek.

It is understood that when King Taksin saw that encircling the Burmese unseen was no longer feasible, he ordered the return of both Phraya Nakhon Sawan’s and Phraya Mahamontian’s armies.

Third Phase of the Campaign

When Acha Wunkyi saw the Thai forces that had camped along the river south of Phitsanulok moving away in several detachments, he sent Kalabo to lead a force to intercept and cut off the supply lines bringing provisions into Phitsanulok. The Burmese succeeded in raiding these supply lines multiple times.

On Friday, the 12th day of the waning moon, third lunar month, a report arrived from Bangkok stating that the Burmese had advanced through the Singkhon Pass and captured Kui and Pran cities. Krom Khun Anuraksangkharm, who defended Phetchaburi, led troops to set an ambush at the narrow pass in Phetchaburi province.

King Taksin, fearing the Burmese might invade Bangkok from this new direction, ordered Chao Prathumphaichit to lead a force back to defend the capital, causing the royal army to withdraw further.

Meanwhile, the Mon forces assigned by King Taksin under Phaya Cheng to ambush the Burmese at Kamphaeng Phet reached the area before the Burmese, who then set a blockade. When the Burmese forces moved from Sukhothai to Kamphaeng Phet, Phaya Cheng launched a surprise attack. The Burmese, taken unaware, fled, leaving weapons which were sent to King Taksin. However, as the Burmese elephant corps caught up, Phaya Cheng had to retreat, resorting to guerrilla tactics to gather intelligence on the Burmese.

The Burmese forces at Kamphaeng Phet were ordered by Acha Wunkyi to attack Nakhon Sawan, a crucial Thai supply depot, aiming to weaken the Thai forces aiding Phitsanulok.

King Taksin, aware of the Burmese strategy, ordered Phraya Ratchaphakdi and Phraya Phiphatkosat to retreat and join Phraya Rachasetthi in defending Nakhon Sawan. When the Burmese arrived at Kamphaeng Phet, Thai scouts reported strong defenses in Nakhon Sawan, causing the Burmese to halt and establish camps only at Kamphaeng Phet. They also dispatched guerrilla units through the western forests to circle behind Nakhon Sawan toward old Uthai Thani.

On Saturday, the 13th day of the waning moon, third lunar month, King Taksin received reports that the Burmese at Kamphaeng Phet had set camps at Ban Non Sala, Ban Thalok Bat, and Ban Luang, and that a division had moved toward Uthai Thani, burning parts of the town, though the Burmese route remained unknown.

On Tuesday, the 2nd day of the waxing moon, fourth lunar month, Phraya Rattanaphimol, defending the Pak Ping camp, reported Burmese scouts clearing forest to establish a camp in Khlong Ping, about three river bends away. King Taksin ordered Luang Wisut Yothamat and Luang Ratchayotathep to bring eight wagon-mounted cannons to reinforce the western side of Pak Ping camp. That same day, the Burmese set camps close to Phraya Thamma and Phraya Nakhon Sawan at Ban Khaek (four camps) and began clearing paths to establish a surrounding camp.

On Wednesday, the 3rd day of the waxing moon, fourth lunar month, King Taksin personally inspected from Tha Rong camp up to Ban Khaek, where the Burmese had established their encirclement camps. He ordered Phraya Siharajdechochai and Khun Tip Sen to join forces to support Phraya Nakhon Sawan in defending the camps, then returned to Tha Rong camp. During this council, the Burmese raided the Pak Ping camp, so King Taksin commanded Chaophraya Chakri to defend the royal camp while he led a fleet downriver from Tha Rong to aid Pak Ping. They remained until dawn, and seeing the Burmese did not advance further, King Taksin entrusted Phaya Thep Aroon and Phichit Narong with management of Pak Ping camp, then returned to Phitsanulok.

That night, upon arrival at Pak Ping, the Burmese attacked Phraya Thammatralok’s camp by Khlong Krapuang canal at 11 p.m. The fighting lasted until dawn. King Taksin crossed the pontoon bridge westward, personally leading reinforcements to defend Khlong Krapuang camp. He ordered Phraya Sukhothai to advance and establish wing-shaped camps with trenches linking to the besieged camp. He also sent Luang Raksa Yotha and Luang Phakdi Songkhram to establish camps adjacent to the Burmese near Khlong Krapuang. Luang Senapakdi led the Kaew Jindai forces to flank and attack the Burmese rear.

On Saturday, the 6th day of the waxing moon, fourth lunar month, the combined forces of Phraya Sukhothai, Luang Raksa Yotha, and Luang Senapakdi launched an assault on the Burmese camp at Khlong Krapuang. Despite fierce fighting and close combat, the Burmese, having superior numbers, held their ground.

On Sunday, the 7th day of the waxing moon, King Taksin ordered Chaophraya Intharaphai, commanding the Tha Rong camp, and the Mon forces under Phaya Klang Mueang to move down and assist in fighting the Burmese at Khlong Krapuang. He commanded the camps to be extended with wing-shaped outposts for a distance of 22 sen (about 2.15 kilometers). At dusk, the Burmese again launched raids on the Thai camps, engaging in battle. Unable to capture the camps, the Burmese settled in to siege positions. King Taksin then ordered Phaya Yamrach to come down from Wat Chan camp, granting him full authority to command all Thai forces fighting the Burmese at Khlong Krapuang.

Around Tuesday, the 9th day of the waxing moon in the 4th lunar month, Acha Wunkyi ordered Kalabo to lead forces to attack the Thai camp north of Pak Ping. Kalabo set up camp near Phraya Nakhon Sawan’s position on the west bank of the Kwai Yai River at Ban Kaek. On Thursday night, Kalabo sent troops across the river to raid the Krom Saeng Nai camp at Wat Prik on the east side. The defenders, only 240 men, could not hold the camp, and the Burmese captured all five eastern camps.

By Friday, the 12th day of the waxing moon, Phraya Nakhon Sawan reported that the Burmese had encircled his camp down to the riverbank and attacked the Wat Prik camps, breaking all five. Seeing the Burmese attempt to flank, he requested permission to withdraw his forces to the east side. King Taksin then ordered the royal army defending the palace, together with Phra Horathibodi’s forces at Khok Salud and Phraya Nakhon Chai Si’s troops at Pho Pratab Chang, to advance to Pak Ping. Mon troops under Phraya Klang Mueang, along with other forces combined as the Phra Yamarat army, marched to fight the Burmese at Wat Prik.

When they set camp, Kalabo attacked again. The Thai forces were initially unprepared, and the Burmese seized the camp. However, when the Phra Yamarat army arrived with full strength, they recaptured the camp, forcing the Burmese to retreat. Both sides then prepared for further battle. Meanwhile, Acha Wunkyi sent his younger brother Mang Yayoung to lead another Burmese force across the river to flank the royal army at Pak Ping from the east side, setting up multiple camps close to the royal army.

Fighting lasted several days, but the Thai forces could not break the Burmese lines. King Taksin realized the enemy was too strong and that staying at Pak Ping risked defeat. On the 10th day of the waning moon, 4th lunar month, he ordered the royal army to withdraw to Bang Khaotok in the Phichit region. Other government troops also withdrew in order.

Fourth Phase of the Campaign

Chaophraya Chakri returned to Phitsanulok and, after consulting with Chaophraya Surasi, agreed that their forces could no longer hold the city due to severe food shortages. They decided to abandon Phitsanulok. Troops stationed near the Burmese lines withdrew back inside the city. The Burmese closely followed, surrounding the city walls. Thai soldiers defended the city walls with artillery fire, preventing the Burmese from entering. The Burmese then withdrew to their own artillery positions and returned fire.

On Friday, the 11th day of the waning moon in the 4th lunar month, the two Chaophrayas learned that the royal army had already retreated the day before. They ordered their troops to increase artillery fire beyond previous days and raised music bands to create the illusion that they intended to hold the city for a long time. Then, they organized their forces into three divisions. Once the formations were ready, at 9 PM, the city gates were opened, and the army marched out to attack the Burmese camps to the east. The Thai forces broke through the Burmese lines, opening a path forward. The two Chaophrayas quickly advanced toward Ban Mung Don Chomphu.

Many civilians followed the armies. Some scattered and fled to join the royal army at Bang Khaotok, while others, exhausted, were captured by the pursuing Burmese. The two Chaophrayas then crossed the Banthat Range to regroup their troops at Phetchabun. Meanwhile, the Burmese besieged Phitsanulok for four months before capturing the city.

Knowing the Thai army had fled Phitsanulok, Acha Wunkyi occupied the city. Seeing the severe shortage of supplies, he dispatched two armies: one led by Mang Yayoung toward Phetchabun to gather provisions from Phetchabun and Lom Sak to send onward, possibly to harass the Chaophrayas again; another led by Kalabo advanced from Kamphaeng Phet to scout for supplies.

Shortly after, Acha Wunkyi received news that King Anawrahta had died and that Jingguja Rajabhutta ascended the throne, ordering all armies to return to Ava swiftly. Alarmed, Acha Wunkyi hastily gathered spoils and captives and retreated via Sukhothai, Tak, and Mae Lamao Pass, instructing Kalabo’s forces to await Mang Yayoung’s return before withdrawing together.

This left two Burmese armies stranded in Siamese territory, requiring months more of Thai efforts to suppress them. The Thai forces led by Phraya Phon Thep and Phraya Ratchaphakdi, moving toward Phetchabun, encountered Mang Yayoung’s forces near Ban Nai Mu south of Phetchabun. After heavy fighting, the Burmese fled north into Lan Chang territory and eventually retreated to Burma via Chiang Saen.

When King Taksin reached the royal camp at Chainat, he ordered Krom Khun Anuraksangkhom, Krom Khun Ramphu Bet, and Phraya Mahasena to attack Kalabo’s forces stationed at Nakhon Sawan and then follow with the royal army. However, by the 1st day of the waxing moon in the 8th lunar month, some unknown event occurred, and by the 3rd day of waxing moon, the king had returned to Thonburi without further details recorded.

The forces of Krom Khun Anuraksangkhom, Krom Khun Ramphu Bet, and Phraya Mahasena advanced to attack the Burmese camp at Nakhon Sawan, where the enemy numbered just over 1,000. The Thai army assaulted the camp, and the Burmese resisted fiercely, fighting in close combat for several days. King Taksin then led the royal army from Thonburi up to Chai Nat. Upon arrival, he received news that the Burmese had abandoned the camp at Nakhon Sawan and fled toward Uthai Thani. The king ordered the armies of Phra Yamarat, Phra Ratchasuphavadi, and the Mon forces under Phraya Ramanyawong to join forces with the army of Chao Anurutdeva, who had moved down earlier. Together, they pursued and defeated the Burmese at Ban Doem Bang Nang Buat in Suphanburi province. The Burmese fled toward the Three Pagodas Pass.

On Thursday, the 9th lunar month, waning moon day 2, King Taksin led the royal army from Chai Nat up to Tak. He ordered commanders to patrol and pursue the Burmese, capturing over 300 prisoners. The Burmese had fully retreated beyond the kingdom’s border, so the king returned to Thonburi.

This campaign of Acha Wunkyi’s northern invasion lasted from the 1st lunar month of the Year of the Sheep (2318 BE) until the 10th lunar month of the Year of the Monkey (2319 BE), a span of ten months. The war ended without a clear victory for either side.

Regarding the conflict of Acha Wunkyi in 2318–2319 BE, historical records remain somewhat unclear. Prince Damrong Rajanubhab (Krom Phraya Damrong) held that neither side won. However, Professor Khajorn Sukpanich, citing Burmese chronicles such as the Hokkew edition, Sir Arthur Phayre’s Burmese history, and Thai memoirs, argued otherwise.

The Hokkew Burmese chronicle records that after capturing Phitsanulok, Acha Wunkyi clashed with King Taksin’s forces at a river junction. Upon learning that King Mangra had died and his son Jingguja (Singu Min) had ascended the throne, Acha Wunkyi was ordered to retreat swiftly to Ava. When he returned, Acha Wunkyi—previously renowned for victories against China—was demoted and punished for poor leadership and lack of discipline, and for using ineffective tactics against the Thais.

This aligns with Sir Arthur Phayre’s account stating:

“…At the end of the rainy season, Mahasi Hsura (Acha Wunkyi) led an army through the Raeng Pass, met weak resistance, but internal disputes arose. The deputy commander Zeya Kyo disagreed with the battle plan, but Mahasi Hsura followed his own plan, capturing Phitsanulok and Sukhothai, yet suffered a crushing defeat and shameful retreat to the border… Many officers were executed; Mahasi Hsura was stripped of rank and disgraced…”

The Thai memoirs note:

“…In the Year of the Dragon, Mottama fell; Phraya Jeng and his Mon followers fled for protection under the king; Phraya Jabaan in Keng did not come down; the king led an unsuccessful attack, retreated and then returned to attack Chiang Mai again. At the end of the year, the Burmese pursued on five routes, with armies of ten thousands. Battles lasted three years; losing Phitsanulok, the Burmese dug tunnels into camps but were routed, and the king’s forces captured many Burmese, scattering their army…”

These sources show that while Acha Wunkyi initially captured Phitsanulok, King Taksin eventually routed his forces (Paradee Mahakhand, 1983: 24–25).

Note:

“Acha Wunkyi” is a Burmese noble title, known either as “Ahta Wunkyi” (Great Minister in charge of military taxes) or by royal style as “Wunkyi Mahasi Hsura.”

During the Thonburi period, the chronicles describe Acha Wunkyi as a key Burmese royal commander who had victories in China. In 2317 BE, when King Mangra prepared to invade Thonburi, he enlisted Mon forces to open roads. The Mon, displeased, rebelled and took Mottama, then launched attacks on Thaton and Hanthawaddy, intending to reach Yangon. Acha Wunkyi led forces to suppress them, pursuing the Mon down to Mottama. Phraya Jeng and other Mon leaders fled to seek refuge under the Thais at the Three Pagodas Pass.

Later, King Mangra ordered Acha Wunkyi to plan an invasion of Siam. Acha Wunkyi prepared his army by dividing it into two forces, advancing through Tak and pushing forward as far as Sukhothai. He then attempted to besiege Phitsanulok for a long time, where Chaophraya Chakri was acting as governor. Acha Wunkyi admired Chaophraya Chakri’s military skill so much that he requested to see him in person. Ultimately, the Thai forces were forced to abandon the city due to lack of supplies. This happened at the same time as King Mangra’s death. Jingguja Rajabhutta ascended the throne and ordered Acha Wunkyi to withdraw the army.

The later life of Acha Wunkyi is recorded differently in various sources, but according to the Thai Historical Encyclopedia, after Jingguja Rajabhutta ordered his withdrawal, he found reasons to strip Acha Wunkyi of his titles and ranks.

Subsequently, Acha Wunkyi allied with Atwan Wunk to depose King Jingguja and handed the throne to Mang Mong. However, Mang Mong ruled for only eleven days before King Bodawpaya captured and executed him. After ascending the throne, King Bodawpaya appointed Acha Wunkyi as viceroy, governing the southern provinces from Mottama until his death in 1790 CE (B.E. 2333).

The Ninth War: Burmese Invasion of Chiang Mai, | Year of the Monkey, B.E. 2319

The cause of this war was that King Jingguja, who had recently become the King of Ava, desired to conquer Chiang Mai, one of the 57 cities in the Lanna Thai region. He organized a Burmese-Mon army under Amalok Wunk as commander, with To Wunk and Phraya U Mon as deputies, advancing from Burma to join forces with the army of Po Ma Yung Wan stationed at Chiang Saen, intending to attack Chiang Mai together.

At that time, Phraya Ja Ban, whom King Taksin had appointed as Phraya Wichian Prakan, had ruled Chiang Mai since it was captured from the Burmese. Seeing the approaching Burmese army and recognizing the city’s limited defenses, he sent a report to Thonburi. Phraya Wichian Prakan then evacuated his family and fled Chiang Mai down to Sawankhalok.