King Taksin The Great

Chapter 13: King Taksin’s Royal Duties in Arts and Culture

13.1 Dress culture during the Thonburi period: How did King Taksin, male officials, commoners, and women dress?

13.1.1 Royal Attire

“…The style of dress during the Thonburi period largely continued the customs of the late Ayutthaya era. However, some elements are evidenced as being uniquely of the Thonburi period, and can be categorized as follows:

King Taksin the Great

Hairstyle and Headgear – He wore the Mahatthai hairstyle, which historical records confirm had already been in use by Thai men during the reign of King Prasat Thong. According to Van Vliet, ‘From above the ears up, the hair was carefully trimmed short. The closer to the neck, the shorter it became, and below that, it was shaved completely.’

Somdet Chao Phraya Borom Maha Sri Suriyawong (Chuang Bunnag),

photographed by John Thomson in 1865, wearing the Mahatthai hairstyle.

Mom Rachothai (M.R. Kratai Isarangkun),

author of Nirat London, photographed by John Thomson in 1865, wearing the Mahatthai hairstyle.

(Image from Thai Costumes: Evolution from Past to Present, Volume 1)

This is known as the Mahatthai hairstyle, in which the hair is shaved around the head, leaving a patch of hair about 4 centimeters long at the crown. This patch would then be combed and styled in a way considered graceful and proper.

Mahatthai hairstyle

(Image courtesy of Muang Boran – Ancient City)

Male royalty wore their hair in the Mahatthai or Lak Chao (rudder post) style—traditional hairstyles that Thai men had worn since ancient times. This custom continued until the reign of King Rama V, when Western-style haircuts began to gain popularity. The photograph, sourced from the National Archives, does not specify the year it was taken.

(Image from the book “Samutphap Mueang Thai” – A Pictorial Album of Thailand)

Wore a slanted royal hat (Phra Mala Biang) and gracefully curved royal footwear.

(Image courtesy of Muang Boran – Ancient City)

At times of warfare, it is likely that the king wore the slanted royal hat (Phra Mala Biang), as this crown was not heavily decorated but made from sturdy materials suitable for practical use. The Phra Mala Biang was made of leather, shaped like a cut gourd, with a brim all around, lacquered black and attached around the collar and ears. It was said to resemble Japanese armor (Sanun Silakorn, 1988: 144).

As for the royal footwear (Chalong Phra Bat), normally the king wore the curved royal shoes, but during warfare they were of the type made from leather. The king’s attire would vary according to different royal occasions, such as

If the king proceeded to visit foreign dignitaries, he would wear six primary royal regalia items: a ceremonial robe of Asawari patterned silk; an outer robe edged with bands of bronze, gold, and green; the principal crown adorned with a tall chada, jewels including diamonds, rubies, and emeralds matching the robe’s colors; intricately embroidered royal trousers; a jeweled royal belt; and the sheathed royal sword—making a total of six items.

If he attended a royal cremation at Wat Chaiwatthanaram, traveling by the royal barge, he would wear only these six items: a ceremonial western-style robe; an outer robe woven with silver thread; the principal crown with jeweled chada matching the robe; embroidered royal trousers; a jeweled belt; and the sheathed royal sword.

If he journeyed to Phra Phutthabat (the Buddha’s footprint) traveling upriver to Tha Chao Sanuk on the royal barge, he would wear seven items: double-layered curved embroidered royal trousers; pleated royal cloth wrapped as a loincloth; a raised-ring ceremonial robe; jeweled belt; the five-pointed fresh-flowered crown; the sheathed royal sword; and a royal parasol—altogether seven items.

If the king led a royal procession from Tha Chao Sanuk to Phra Phutthabat, he would wear only four items: a traveling robe; curved embroidered royal trousers; jeweled belt; and the European-style crown with feathers and plumes.

If He proceeded to Pak Pa Thung Ban Mai, He would remove the royal traveling attire and then be presented with the garments for the royal barge, which would accompany Him from the capital. Upon reaching Than Kasem, He would again change attire. At afternoon time, when He was to proceed to pay homage at the Buddha’s Footprint, these garments would be presented: If He rode the royal elephant Phut Thal Thong, He would wear only eight items, namely: royal pants with double-curled cuffs, one; pleated loincloth, one; jackfruit-patterned sash, one; inner golden brocade robe with raised floral motifs, one; white crinkled outer robe, one; patterned sash, one; white crown with golden rim matching the color, one; royal sword, one — totaling eight items.

Upon arrival at the Buddha’s Footprint, He would proceed to tour the forest. If riding the royal elephant for the excursion, or riding a ceremonial horse, either was allowed. Should He go to Wat Phra Si Sanphet and consecrate the temple, He would wear a high gourd-shaped headdress with erect feathers, one; patterned white ground robe, one; Japanese-style ceremonial robe or ceremonial attire, one; royal palanquin with roof, or bare palanquin, both permitted; royal pants with double-layered cuffs embroidered with various jewels and strung with pearl necklaces; dragon embroidery adorned with jewels, one; pleated striped loincloth in green, red, purple, gold with jewel embroidery along the edge, one; sword sheath hanging with gold tassels, one; golden-bordered ceremonial robe with ruby-colored raised embroidery, hanging with a jeweled chain netting of pearls, with flower motifs, one; green ground golden-bordered royal cape embroidered as a net with gold tassels and leaf-shaped gold necklaces hanging, one.

For the Great Victory Chariot and the royal barge accompanying Him to bestow the Royal Kathin robe, He would wear as follows: a gold chest band inlaid with red gems, one; royal crystal necklace adorned with rubies and emeralds, one; jeweled ornamental fringe, one; jeweled ornamental side fringe hanging at the front, one; Great Victory royal crown, one; jeweled floral earrings with emerald drops, one; royal ring, one; gold wristbands with royal enamel and gem inlays, one; gold footwear with royal enamel and gem inlays, one — totaling thirteen items.

For the royal war attire suitable for elephant combat, He would wear: royal pants with inner royal lining, one; dyed ceremonial robe with inner royal lining, one; black silk pants as outer armor, one; padded ceremonial robe as outer armor, one; royal crown with inner royal lining, one; tilted royal crown, one; black brocade sash, one — totaling seven items.

If He were to proceed to capture animals at Lopburi, Sakaeo, Nam Jon, to surround tigers, to climb elephants to catch tigers, to go to Phon Chang to capture elephants, and to catch elephants in the fields, He would wear the traveling attire with the high feathered headdress…

(From the book Somdet Phra Chao Taksin Maharaj by the Committee of the Somdet Phra Chao Taksin Maharaj Foundation, 1980: 144–147; and Thai Dress: Evolution from Past to Present, Volume 1, 2000: 202–204)

13.1.2 The attire of government officials, according to the records in the Phra Tamrap Khrueang Ton concerning the manual that prescribes the powers and duties of the Chao Thi (officials), police, and royal pages, is described as follows:

For government officials participating in full ceremonial royal rites, the Hua Muen (chief of ten thousand), Nai Wern (attendants), Ja (sergeants), and royal barge crew would wear patterned sompak trousers, drape the khrui robe, wear pok (a type of shoulder cloth), and fasten a kiao sash according to their rank, with a sword belt worn in accordance with their position.

Ordinary royal pages would wear patterned trousers, drape the khrui robe, and wear the pok kiao (pok with sash).

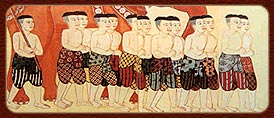

A colored painting depicting the royal procession by land during the Ayutthaya period, reproduced from the mural paintings in the ubosot of Wat Yom, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya Province (image sourced from the book Somdet Phra Chao Taksin Maharaj).

A colored painting recreating the attire of the royal pages (mahadlek)

(image sourced from the book Somdet Phra Chao Taksin Maharaj).

For the Chao Thi of the Krom Chao Thi, whose duty was to maintain order in buildings and premises, their attire for royal ceremonies was as follows: senior ranks wore patterned sompak trousers, draped khrui robes, wore pok kiao, and wore sword belts.

Regarding the police, who were divided into four departments — Outer Police (one left, one right) and Inner Police (one left, one right) — the regulations stated:

When His Majesty attended performances, the head of the department (Krom Palat Krom) wore patterned sompak trousers and draped khrui robes; the department chiefs wore sword belts, the chief sergeants wore sword belts and carried spears; the officers (Tohnai) wore silk trousers with long hems, sashes, and sword belts, accompanying the royal procession.

For less grand occasions:

Patterned sompak trousers, khrui robe, sword belt.For dangerous duties such as observing tigers in the palace:

Silk trousers and sash.When marching out of the palace for such duties:

Silk striped trousers, winter coat, sash.For regular events such as palace parades or minor events outside the palace:

Normal duty: Patterned sompak silk trousers, draped khrui robe, sword belt.

Full ceremonial dress: Patterned sompak trousers, khrui robe, pok kiao according to rank.

Full ceremonial procession: Patterned sompak trousers, winter coat, jeab-baad sash; department chiefs wore sword belts, deputy chiefs wore sword belts, chief sergeants carried spears and wore sword belts; officers wore sword belts.

Note:

The term “winter coat” refers to the garment called the inner shirt.

Hats during King Narai’s reign for soldiers included styles such as the Dok Lamduan (Lamduan petal) hat, leather hats, Western-style hats, and excursion-style hats; hairstyles were kept in the traditional Mahadthai style.

Generally, uniforms for warriors and nobles were sewn from silk and muslin fabrics. The sanob shirt or annually bestowed woven cloth was worn only during royal ceremonies or when accompanying the King on excursions. It was not for everyday use. When worn out, the official had to respectfully request a new garment from the royal grant.

King Taksin bestowed upon Chaophraya Mahakasatsuek a dark sanob shirt embroidered with large naga floral patterns, a six-khuep white lotus petal patterned cape, a six-khuep patterned cape with window pane designs, and royal pants with curled cuffs.

The royal rewards for nobles victorious in war, according to the Manthiraban Code, included:

Officers who went to battle and won were awarded gold badges, sanob shirts, and land grants for their descendants’ support.

Those who killed an elephant in battle were granted gold hats, gold sanob shirts with raised cuffs, 10,000 rai of land, and were entitled to share in gold and silver offerings.

Additionally, the Manthiraban Code described other noble attire: nobles with a 10,000-rai fiefdom wore gold-tied hairpieces; seated lords wore golden tied hairpieces; and those holding a 10,000-rai fiefdom with towns wore gold crowns.

Noble attire included khrui robes sewn from hemp fabric (presumed to be lightweight, sheer fabric) with hems reaching mid-calf.

The Sena Kut shirt is a military uniform worn by both army and navy personnel dating back to the Ayutthaya period. It is made of patterned cotton fabric imported from India and tailored in the Chinese style, featuring buttons fastened along the right side seam. The front, back, and both upper sleeves are decorated with a lion biting armor motif. Today, only two such shirts remain, preserved at the National Museum Bangkok. The shirt shown in this image is housed at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, Canada.

(Image sourced from the book Thai Dress: Evolution from Past to Present, Volume 1)

The outer shirt was tailored from silk fabric imported from China or Europe, embroidered with gold thread in intricate patterns. It featured a front opening with buttons woven from silver or gold thread spaced along the closure. The sleeves had wide cuffs. The fabric used is presumed to be Indian or Persian gold brocade textiles, such as Khem Khab, Atlat, or Yiarbab.

The scarf worn around the neck was made of Chinese silk embroidered with silver or gold thread, or sometimes the finest available fabric, likely Indian or Persian gold brocade such as Khem Khab, Atlat, or Yiarbab, which were highly valuable and expensive textiles.

The royal pants (sanaplao) were made from fine fabric embroidered with gold and silver threads in patterns around the lower leg, extending below the knee.

The wrapped loincloth (chong kraben), according to records, was worn over the royal pants in the style of a traditional wrapped loincloth.

Footwear consisted of slip-on shoes similar to those worn by the Moors, resembling sandals.

The Lom Pok was a noble’s hat, also called Pok or Kiao, serving as a rank marker among nobles. It was a pointed hat resembling a crown, with a brim banded in yellow or gold thread for decoration. Above the band was a circular kiao ornamented with golden floral motifs, tapering to a point. Sharewès notably described the classification of noble ranks based on the betel nut boxes and Lom Pok hats in an intriguing manner.

Okya — the highest-ranking ruling class — wore a Lom Pok (noble hat) with edges made of gold and a pointed top adorned with a garland of flowers (chor mala).

Okphra — second-tier nobles — wore a Lom Pok with edges decorated by a Chaiyaphruek floral motif.

Okluang — third-tier nobles — wore a Lom Pok with edges about two inches wide, crafted with less finesse compared to Okphra.

Okkhun — fourth-tier nobles — wore a Lom Pok edged in polished gold or silver.

Okmuen — fifth-tier nobles — wore Lom Pok edges made of polished gold or silver, similar to Okkhun.

Regarding the wearing of Song Pak or Som Pak cloth for officials, the most important garment was the Song Pak, a royal fabric bestowed by the monarch symbolizing rank and affiliation. This cloth was worn during audiences or when accompanying royal processions. Even when leaving home to enter the palace, other cloths were worn first, and the Thonai (attendant) carried the Som Pak cloth to assist the official in donning it within the royal precincts. Mural evidence shows this practice occurring near the palace walls beside the throne hall.

The Song Pak or Som Pak is a narrow silk fabric that is joined (called phlaw) by sewing two pieces together, resulting in a width of about 160 cm — wider than ordinary loincloths by one-quarter, and longer by half. For full ceremonial dress, richly patterned Som Pak fabrics were used; for regular audiences, Som Pak in various silk colors was worn. The most prestigious Som Pak was the Som Pak Pum, woven with silk and featuring floral eyelet patterns, while the simplest grade was the Som Pak Riw (striped pattern).

The method of wearing Som Pak differs from the regular chong kraben (wrapped loincloth) due to the fabric’s greater length and width. To begin, the cloth is divided into a short side and a long side. The short side is measured as for a normal chong kraben and the edge is tucked in as the first step. The longer side is then folded to match the short side and brought toward the body. The excess fabric at the upper edge is tucked under the first tuck, pulled upward to create a fabric edge shaped like an elephant’s mouth — this pulling is called chak pok (pulling the edge). The fabric edges differ in thickness: the right side has a single fold, while the left side has a double fold. These two edges are overlapped and rolled into a shape similar to a regular chong kraben but thicker. The garment is then pulled through the legs and tucked in at the waistband just like the ordinary chong kraben.

In documents from the Ayutthaya period, the term “kiao” frequently appears in regulations concerning the attire of government officials. Somdet Chao Fa Krom Phra Naritsaranuwattiwong defined “kiao” as a waistband, while “kiao lai” specifically refers to a patterned waistband.

Yan Phat-style Waistband Wrapping

Wrapped Waistband Tying

Wrapping the Headcloth

Wrapping the Gelai Cloth

(Image sourced from the book Thai Dress: Evolution from Past to Present, Volume 1)

There was a style of wearing cloth called “Nung Baep Kiao Gelai” (wearing in the kiao gelai style), which required two patterned pieces of fabric. Somdet Chao Fa Krom Phra Naritsaranuwattiwong defined it as follows:

“One piece is worn as a chong kraben (wrapped loincloth), while the other is worn as a waistband (kiao). The waistband is tied by pulling the back portion wide to cover down to the buttocks. At the front, it is gathered and knotted; one side of the cloth’s edge is tied at the knot, while the other side is left to drape loosely downward, then folded back and tucked into the waistband, resembling a bag hanging in front of the leg. It is understood that the wrapped cloth is called the ‘nung’ (loincloth), and the tied cloth is called the ‘kiao’ (waistband). Previously, the nung and the kiao were probably different types of fabric — the nung was wider, and the kiao was narrower. Later, this distinction was lost, and people sometimes used the nung cloth itself as the waistband, leading to some confusion in terminology, with the cloth being called either patterned nung or patterned kiao accordingly.”

The term “kiao” also applies to wearing a sash or belt over a shirt. When a sash is worn over the outer garment, it is called kiao. If a silver or gold belt is used, it is called kiao pan neng (belt sash). If a decorative cord is used, it is called kiao rad prakot (cord-tied sash). When an embroidered cloth called jiarabat is used, it is referred to as kiao jiarabat.

(Source: Thai Dress: Evolution from Past to Present, Volume 1, 2000: pp. 208, 214–216)

Commoner Men’s Attire

Commoner Men’s Attire

(Image sourced from the book Somdet Phra Chao Taksin Maharaj)

13.1.3 Commoner men’s attire included wearing chong kraben (wrapped loincloth), thok Khmer style pants, loi chai style pants, or sarong with a waistband. Most men kept their hair short and commonly wore hats during warfare, presumably for protection against weapons.

Women’s attire

Female court officials (royal ladies-in-waiting)

For the inner court officials’ attire or women’s clothing, silk fabrics were worn in graduated ranks according to status, with different types of silk named after their patterns, such as Phrae Dara Korn Lew, Phrae Jamruat, Phrae Khaorop, Phrae Lai Thong, and Phrae Dara Korn. One could identify an official’s rank by their garments and fabric types as follows:

Queen Consort: wore golden-patterned silk skirts, matching blouse, and golden footwear

Royal Consorts: wore golden-patterned silk skirts, matching blouse, and golden footwear

Royal Princesses: wore Phrae Dara Korn silk skirts, matching blouse, and velvet footwear

Luang’s children: wore Phokla gold-patterned blouses (did not wear footwear)

Luang’s grandchildren: wore Phrae Dara Korn Lew silk blouses

Royal concubines: wore silk of various colors

Wives of officials ranked higher than ministers: wore Phrae Khaorop silk skirts

Wives of minister-ranked officials: wore Phrae Jamruat skirts and blouses

Ladies-in-waiting (Nang Nai): wore pleated skirts and draped shoulder cloths (sabai)

These garments were prescribed to be worn only during royal ceremonies. On ordinary days, everyone wore similar simple cloth wraps and drapes.

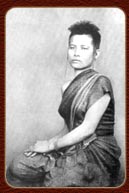

Ladies in the reign of King Rama IV (circa 1801–1868 CE) wore chong kraben (wrapped loincloth) secured with a gold belt adorned with a jewel-studded clasp. They draped a sabai (shoulder cloth) pleated with Chinese silk.

(Image sourced from the book Thai Dress: Evolution from Past to Present, Volume 1; Album of Thailand)

Commoner women typically wore chong kraben in dark colors such as black or dark green (tapun green). They draped a sabai diagonally across the shoulder, with accessories including bracelets, pendants, necklaces, rings, and belts. Hairstyles were generally short winged cuts, though some evidence shows that the winged shoulder-length style was still occasionally worn.

(Source: Somdet Phra Chao Taksin Jom Bodin Maharaj, unpublished, pp. 135–138; Siam Arya 1(4), October 2002, pp. 87–88 by Apisit Laisatru Klai, and Foundation for Preservation of Ancient Monuments in the Old Palace, 2000, pp. 116–120)

Note:

In late Ayutthaya, women’s hairstyles had four main styles:

a) Central bun on top of the head

b) Winged hairstyle

c) Raised hair with rak krang (a hair accessory)

d) Shoulder-length hair

Women often combined the winged and shoulder-length styles, with the top of the head styled in wings and the hair flowing down to the shoulders on both sides. Additionally, the winged style was sometimes incorporated into the bun hairstyle.

Terid

(Image sourced from the book Somdet Phra Naresuan Maharaj)

It is also observed that the winged hairstyle (pom piik) might have been worn beneath a head ornament, such as a terid (ceremonial crown) or other types of crowns.

The practice of wearing shoulder-length winged hair among women is believed to have originated in the royal court and gradually spread to the general population. After the fall of Ayutthaya, women reportedly cut their hair short to just the winged style for practical reasons—facilitating combat and disguising themselves as men. At that time, aesthetic considerations were less important, as the closer they resembled men, the safer they were.

In later periods, the winged hairstyle involved cutting the hair short around the crown in a circular shape following the hairline to form the “wings,” while shaving the remaining hair, leaving only a patch resembling banyan tree roots (rak sai). Wearing the winged hairstyle alone still appears occasionally, such as in depictions of the Vessantara Jataka procession, believed to have been painted in late Ayutthaya.

For children, it was customary to wear their hair in a topknot. When they grew older and the topknot was cut off, a circular hairline or hair whorl remained where the knot had been tied, surrounding the rest of the hair. This is called the “rai phom” (hairline). The rai phom refers to the area where hair was either plucked or shaved, such as the rai wong na (frontal hairline) and rai juk (topknot hairline).

The rai wong na helped to shape the face, creating a clean, rounded contour like a full moon. The rai juk, which remained on the scalp, indicated youthfulness. Women who wished to preserve their youthful appearance often plucked the hair around the rai juk in a neat circle at the crown of the head. This practice is reflected in phrases such as “applying oil to the hairline” and “a smooth, well-maintained hairline.”

Noblewomen traditionally wore the winged hairstyle (pom piik), a style that Thai women have worn since ancient times. Unlike men, women groomed their hairline above the forehead to enhance beauty and often styled side locks called jon hu (ear curls), sometimes referred to as pom tat (hair ornament).

This winged hairstyle persisted until the reign of King Rama V, when fashion shifted toward long hair in accordance with royal preference. Later, the dok kratum hairstyle (a floral-inspired hairdo) became popular.

(Reference: Thai Dress in the Rattanakosin Era; Image from the National Archives, photographer and date unknown; also from Album of Thailand)

The term “pom piik” (winged hairstyle) refers to a specific way of styling hair where the hairline around the head is clearly defined and combed either with a center part or swept back, depending on what is considered most attractive. The style often includes side locks or jon. It is called the “winged hairstyle” because the sharply defined edges of the hairline resemble the shape of wings.

Siamese nobility during the reign of King Rama IV, as described in Karl Dohring’s Siam (page 28), provides a fine example of the traditional winged hairstyle with two side locks (jon)—a style rooted in ancient customs.

(Image sourced from the book Album of Thailand)

“Jon pom” refers to a feature of the winged hairstyle where a long lock of hair is left to hang beside the ear and tucked behind it, thus called “jon hu” or “jon pom.” Those who wore the jon hu typically had to keep the rest of their hair short to complement this style.

As for women’s beauty practices recorded in historical natural and political chronicles from the reign of King Narai, they included: Dyeing their teeth black, Growing long nails, Coloring their nails and fingertips red

Additionally, tattooing was a cultural practice particularly valued among men, as documented in the Lalubér (Laloubère) archives.

The practice of dyeing teeth black was recorded by Nicolas Chéruel in his Natural and Political History during the reign of King Narai the Great. He documented the Siamese people’s customs and beliefs regarding blackened teeth as follows:

What Siamese women could not bear to see in us was that we had white teeth, for they believed that only spirits and ghosts possessed white teeth. It was considered shameful for humans to have white teeth, likened to wild animals. Therefore, when men and women reached the age of 10 to 15 years, they would begin the practice of blackening their teeth to a glossy shine by the following method:

After selecting the person for this ceremony, they were made to lie on their back on the ground and remain in that position for three days throughout the ritual. The first step involved cleaning the teeth with lime juice, then rubbing a certain red-colored solution on them. Afterwards, the teeth were polished with burnt coconut shell, turning them black.

Women undergoing this dental treatment often became very weak because of the harsh chemicals used. They would be so numb that pulling out a tooth caused no pain, and sometimes teeth would fall out when chewing hard food. During these three days, only cold rice porridge was consumed, slowly poured down the throat without touching the teeth. Even a slight breeze could spoil the ceremony, so the patient was carefully covered and kept warm until the pain and swelling in the gums and mouth subsided and returned to normal.

This account reflects the Western worldview and is one of several hypotheses explaining the blackened teeth of the Siamese. Cheruel’s detailed description likely stems from observations made in multiple places, framing his view with those experiences, which means it might not be universally accurate.

In reality, evidence from the Sukhothai period shows that both men and women in Siam chewed betel quid, which stained lips red and teeth black—likely a key reason for black teeth in late Ayutthaya Siam.

Regarding nail dyeing and lengthening, Cheruel noted that Siamese people used the same solution to stain nails and pinkies red. Only high-status individuals kept long, dyed nails, as workers needed short nails for labor, marking a clear social distinction.

The exact method and materials for nail dyeing are unclear but probably involved natural plant dyes, such as the bright orange dye from the stem of the kandikan flower.

(Reference: Thai Dress: Evolution from Past to Present, Vol. 1, 2000, pp. 220–221)

13.2 What were the royal initiatives in the arts, and what was the nature of the arts during the Thonburi period?

Due to the Second Fall of Ayutthaya, many Thai craftsmen were scattered, lost, or killed. A significant number were captured and taken away by the Burmese. Thus, by the Thonburi period, only a few skilled artisans remained. King Taksin of Thonburi had to rely on newly trained and revived craftsmen to construct various permanent structures and artistic objects, both for religious purposes and for royal administration. These efforts were largely carried out by his military and civilian officials, all of whom were knowledgeable in craftwork. It is believed that the King gathered craftsmen from all disciplines to Thonburi to train a new generation. The craftsmen of this era passed down and contributed greatly to the early Rattanakosin period.

Craftsmanship during the Thonburi period was newly reestablished and time for craftsmanship was very limited due to ongoing wars, leaving little time for recovery. The creation of art and artifacts was rushed to meet urgent needs. Furthermore, King Taksin’s reign lasted only 15 years. Therefore, truly exquisite and refined works from the Thonburi period are very rare.

The arts of the Thonburi period can be divided into four categories:

13.2.1 Ships: Shipbuilding flourished during the Thonburi era, including warships, merchant junks, and procession boats used in royal service. In King Taksin’s reign, the royal barges included:

Burlang Kaew Chakrapat

Sri Sawat Ching Chai

Bunlang Bussak Pimarn

Phiman Mueang In

Sampao Thong Tai Rot

Sri Sammat Chai

After King Taksin of Thonburi restored the kingdom’s independence, He graciously ordered the construction of new royal ceremonial barges as follows:

- Suwannaphichai Nawathai Rot

- Srisaklad

- Khom Yad Pit Thong Thueb (Source: Office for National Identity Promotion, 1996 : 112)

13.2.2 Painting in the Thonburi Period

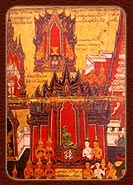

Although the Thonburi era was a time largely occupied by intense warfare, there still existed several exquisite and finely crafted paintings left as lasting memorials. Among the most important pieces, which are still preserved at the National Library of Graphics on Thawathiwat Road, Bangkok, is the “Tri-Poom Buran Illustrated Manuscript, Thonburi Edition” created in 1776 (B.E. 2319).

The “Tri-Poom Illustrated Manuscript” is a picture book written based on Buddhist teachings. Such manuscripts have been traditionally produced since ancient times, and several editions survive today as national cultural heritage, including those from the Ayutthaya and Thonburi periods.

Creating a “Tri-Poom Illustrated Manuscript” is a challenging task. It requires not only the accurate inclusion of Buddhist scriptures but also skilled painters to illustrate the entire volume. The illustrations depict hell, heaven, and various realms correctly and beautifully, making the manuscript visually captivating.

This type of book relies heavily on the paintings as its core element throughout. The creator of such a manuscript must be either a monarch or a person of great power and prestige who genuinely loves and is deeply devoted to both art and Buddhism.

Depiction of the Tavatimsa Heaven (Heaven of the Thirty-Three Gods) — where those who respect and revere their parents and elders of the family, and who possess generosity (non-greed) and great patience (forbearance), will be reborn.

(Image from the book: “King Taksin and the Role of the Chinese in Siam”)

In the section of the Ancient Tri-Purusha Illustrated Manuscript, Thonburi edition, the origin is recorded as follows:

“In the year 2319 of the Buddhist Era, 4 months and 26 days past, on a Tuesday, in the 11th lunar month, the 13th day of the waxing moon, Chula Sakarat year 1138, the year of the Monkey, in the Auttasak era, His Majesty the King (Borommakot) left the throne at the Thep Mansion, Thonburi Sri Mahasamut. Many royal attendants were present.

He examined the stories in the Tri-Purusha manuscript and, with royal intention, wished commoners and monks of the four orders to understand the three realms and the five destinies — the origins of devas, humans, hells, the asuras, preta, ghosts, and animals.

Therefore, he commanded Chao Phraya Sri Thammathirat, the Grand Prime Minister, to prepare fine manuscripts and send them to painters to illustrate the Tri-Purusha. The work was to be done at the Supreme Patriarch’s residence (the first Supreme Patriarch of Rattanakosin), at Wat Bang Wa Yai (present-day Wat Rakhang).

The Supreme Patriarch was to supervise and instruct the painting and inscription to follow precisely the Pali scriptures, with clear and complete explanations, so that it would serve as a proper moral guideline thereafter.”

Thus, the Supreme Patriarch oversaw the creation of the illustrations and captions in the Tri-Purusha manuscript to ensure accuracy, orderliness, and strict adherence to the canonical texts.

This Tri-Purusha illustrated manuscript is therefore considered the definitive standard edition: beautiful in artwork, excellent in content, and comprehensive in all aspects.

The painters who dedicated their exquisite skills to fulfill the royal trust in this work were four persons:

- Luang Phetwakam

- Nai Nam

- Nai Boonsa

- Nai Ruang

Additionally, there were four scribes who assisted in writing the explanatory captions accompanying the illustrations:

- Nai Boonjan

- Nai Chet

- Nai Son

- Nai Thongkham

In the creation of the Traiphum Illustrated Manuscript, His Majesty King Taksin of Thonburi graciously ordered the work to be carried out with exceptional care, meticulousness, and strict attention to detail. In summary, the royal intention behind producing this ancient Traiphum manuscript was to provide the general populace with a correct and accurate understanding of heaven and hell as taught in the Pali scriptures. This would encourage everyone to diligently perform good deeds and refrain from evil actions, guided by the teachings of Buddhism for generations to come.

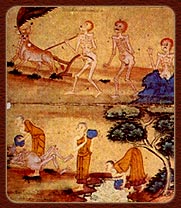

Depiction of Two Types of Pretas (Hungry Ghosts):

Those who incur sin by speaking disrespectfully of the Buddha Kassapa.

Those who incur sin by hoarding water and not sharing it with humans and animals.

(Image from the book “King Taksin the Great and the Role of the Chinese in Siam”)

This Traiphum Illustrated Manuscript of the Thonburi period is considered one of the largest Traiphum manuscripts in Thailand. When fully unfolded, it stretches to a length of 34.72 meters, with exquisitely detailed paintings in color on both sides of the manuscript pages.

The dozens of illustrations contained in this Traiphum manuscript are exceptionally beautiful and impressive, making it difficult to find any other Traiphum manuscript that surpasses it in excellence.

There were two such Traiphum manuscripts commissioned by His Majesty during his reign. The other copy is currently preserved at the National Museum in Berlin, West Germany, having been acquired from Thailand in 1893 (B.E. 2436).

These two Traiphum manuscripts clearly demonstrate that King Taksin of Thonburi was not only the liberator who restored the nation’s independence but also a restorer of artistic craftsmanship, Buddhism, and the moral values of the people. (Sethuon Supasophon, 1984: 6-7, 93-94) In addition to the Traiphum Illustrated Manuscript, there are also mural paintings on the walls of the Phuttha Isawan Throne Hall.

13.3.3 Fine Arts

During the Thonburi period, there were skilled artisans specializing in lacquer work, ornamentation, carving, sculpture, and painting. Important fine art pieces from this era include four lacquered cabinets with water gilding patterns (ตู้พระไตรปิฎกลายรดน้ำ) housed in the Vajirayan National Library, Thawatsukri, Bangkok. There are also several other lacquered cabinets with similar patterns and craftsmanship, indicating that they were likely created around the same time. These lacquered cabinets originated from Wat Ratchaburana, Wat Chantharam, and Wat Rakhang Kositaram, demonstrating that lacquer work with gold leaf water gilding was another branch of fine arts revived during the Thonburi period.

Additionally, there are mother-of-pearl inlaid Tripitaka cabinets located in the mandap and the hall of the Dharma Throne at Wat Phra Sri Rattana Satsadaram (the Temple of the Emerald Buddha).

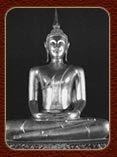

Buddha Image of King Taksin the Great’s Reign (in a simple robe style)

(Image from the book Analysis of the History of Buddhist Worship and Buddha Art in Asia)

Casting:

King Taksin the Great commanded Luang Wijit Narumon to sculpt a Buddha image according to the specified Buddhist iconography. He then had a standing bronze Buddha image and a meditation posture Buddha image cast, such as the principal Buddha image in the ubosot (ordination hall) of Wat Mahathat.

Carving works:

These include the royal bed platform and the platform used for meditation practice (Vipassana).

The royal bed platform of King Taksin the Great, which is enshrined inside a small viharn (chapel) at Wat Intaram near Talat Phlu on the Thonburi side. It is made of two joined wooden boards, measuring 1.76 meters wide, 2.48 meters long, and 5 centimeters thick. The balustrades are made of ivory, and there are intricately carved ivory panels featuring pudtan floral patterns decorating the balustrades all around. It is also equipped with posts for a mosquito net (called “Wisut”).

2. The platform for meditative practice (Vipassana), which is enshrined inside the small ordination hall (Bot Noi) in front of the prang (spire) at Wat Arun Ratchawararam on the Thonburi side, near the old royal palace. This is the original ordination hall of the temple, built since the Ayutthaya period, alongside the original prang (the current prang was built in the reign of King Rama III).

This platform was made from a single wooden plank, measuring 7 feet wide and 20 feet long. Both platforms (the royal bed platform and this meditation platform) are crafted simply and plainly, without any special ornamentation or beauty. Archaeologists consider the craftsmanship somewhat coarse, indicating that these works were made by artisans whom King Taksin had revived and trained anew, but who had not yet attained the skill level of master craftsmen.

The door panels of the ubosot porch and the door panels of the viharn porch at Wat Phra Sri Rattana Satsadaram

(Image from the book The Grand Palace)

In addition, there is a bench from Klaeng District, Rayong Province, which is preserved at the National Museum, Bangkok. Also, there are mother-of-pearl door panels at the ubosot of Wat Phra Sri Rattana Satsadaram and the northern mondop.

13.3.4 Ceramics in the Thonburi Period (corresponding to 1768–1782 CE)

When King Taksin ascended the throne at Thonburi, trade with China began to expand. During this period, Thailand continued to import ceramic ware from China for use. Most of these were Benjarong bowls decorated with Thep Nom patterns and Narasingh motifs, featuring white glaze on the inside, unlike the green glaze common during the Ayutthaya period.

Benjarong Ceramics

During the Ayutthaya period, after the second fall of Ayutthaya in 1767 (B.E. 2310), Chinese ceramics featuring five-color overglaze painting using white, black, red, yellow, and green or blue known as Benjarong, became prominent in Thailand.

Benjarong refers to ceramics with intricate painted patterns on glaze, specially commissioned by the Siamese royal court from Chinese craftsmen. The designs were traditional Thai motifs sent from the Siamese court for Chinese artisans to replicate. Over time, Benjarong ceramics gained widespread popularity among the Thai nobility and aristocracy.

Benjarong Ware

(Image from the book: “King Taksin the Great, Sovereign of the Land”)

Benjarong Ware was elaborately decorated with full patterns, leaving no empty space. During the Ayutthaya period, common motifs included Thepphanom, Narasimha, and flame scrolls, with interiors glazed in green. Later designs featured Rachasri, Garuda, Hanuman, and Kinnari, along with floral and vine motifs. Some patterns were drawn by Phra Ajarn Daeng of Wat Hong Rattanaram and sent to China to produce tiles used at Wat Ratchabophit. (Source: Phusadee Thapthats, 1999)

13.3 Architecture: What kinds of constructions were built during the Thonburi period?

During the reign of King Taksin of Thonburi, it was a time of rebuilding the nation. Numerous constructions were undertaken, including palaces, fortresses, city walls, and royal temples. The architectural style of this period largely continued from the late Ayutthaya era. Building bases featured soft curves like the hull of a Chinese junk, with structures tapering elegantly upwards. Other architectural elements closely resembled those of the Ayutthaya style. Unfortunately, many Thonburi-era buildings were repeatedly restored in later reigns, so their current appearances mostly reflect the style of the most recent restorations. Original traces still evident today include Fort Wichai Prasit, the walls of the old palace, the royal audience hall and twin pavilions in the former royal palace, as well as temples both in the capital and provincial towns that were restored during King Taksin’s reign—later renovated again in subsequent periods. Still, certain structures like the ordination hall and small viharn at Wat Arun, ordination hall and old viharn at Wat Ratchakhrue, the old ordination hall at Wat Intharam, the Red Pavilion at Wat Rakhang Kositaram, and the ordination hall at Wat Hong Rattanaram, retain features representative of Thonburi-period architecture.

Note:

Wat Arun Ratchawararam, located on the west bank of the Chao Phraya River, at the mouth of Khlong Mon and across from Tha Tian Market, is one of Thailand’s most beautiful temples, showcasing Thai craftsmanship from late Ayutthaya through early Rattanakosin.

History of the Temple:

Wat Arun dates back to the Ayutthaya period and was originally called Wat Makok, later changed to Wat Makok Nok, and eventually became Wat Chaeng. It was elevated to the rank of a royal temple by King Taksin, who, after the fall of Ayutthaya, broke through the Burmese lines and arrived at this temple in Thonburi at dawn. Thus, the temple was renamed Wat Chaeng (“Temple of Dawn”). After achieving independence in 1768 (B.E. 2311), he declared Thonburi the capital and expanded the royal palace grounds to Khlong Nakhon Ban, placing Wat Chaeng within the palace boundary. Monks were no longer permitted to reside there, and the temple’s territory became part of the royal compound. King Taksin then renovated the ordination hall and viharn of Wat Chaeng as best as possible within his 15-year reign.

Later, during the Rattanakosin era under King Rama II, the temple was further restored and renamed Wat Arun Ratchatharam. In King Rama IV’s reign, it was restored again and renamed Wat Arun Ratchawararam, the name it officially bears today.

Key Monuments at Wat Arun:

Several ancient structures at the temple are noteworthy, such as the ordination hall, which reflects Rattanakosin craftsmanship, especially from King Rama IV’s period. At the entrance are two demon guardians, each holding a mace—symbols of spiritual protectors warding off evil spirits. These figures reflect classical khon costume art and were sculpted by Phraya Hathakarn Banchach, though they have since been altered through restoration.

The entrance arch features a crown motif, and a cloister surrounds the ordination hall, housing Buddha images in the Maravijaya posture. The principal Buddha image, named Phra Phuttha Thammisarat Lokanath Dilok, is gilded and lacquered, with a lap width of 3 cubits and a span. Interestingly, its face was modeled by King Rama II himself. On either side sit two principal disciples in anjali posture. The interior murals depict the Buddha’s life story, while the inner doors and windows feature traditional Thai patterns.

Another structure is the viharn, housing Phra Champunuth Maha Burut Lakkhana Asiti Anubhapit, with Phra Arun (Phra Chaeng) placed in front. This smaller Buddha image, 50 cm wide at the lap, was brought from Vientiane by King Rama IV, as its name matched that of the temple. To the south of the temple lie the old ordination hall and small viharn, both containing historical relics. The old ordination hall features King Taksin’s meditation platform, crafted from a single plank of wood, measuring 1.67 meters in width. The small viharn enshrines the Chulamani Stupa relic.

Another major monument is the central prang (tower) of Wat Arun. King Rama II initiated its restoration, intending to increase its height from the original 16 meters, but passed away before construction began. King Rama III continued and completed it, including placing the crown spire. However, he too passed away before the consecration. The initial prang was designed by Phraya Ratchasongkram (That Hongsakul), a descendant of Ayutthaya-era artisans. Later, King Rama IV commissioned further improvements, especially the colored tile decorations, completed by Phraya Ratchasongkram (Kon Hongsakul), That’s son. The prang thus spanned the work of three reigns, incorporating restorations and additions up to the present day.

Wat Intharam (formerly Wat Bang Yi Ruea Nok):

This temple held deep personal significance for King Taksin, who frequently performed religious rites, meditation, and retreats there. It is also the site of his cremation and enshrinement of his royal relics.

Today, Wat Intharam is a third-class royal temple located on Thoet Thai Road in Bang Yi Ruea Subdistrict, Thonburi District, Bangkok, covering an area of about 25 rai. Its founding date is unknown, but it is widely believed to date back to Ayutthaya. According to tradition, the Bangkok Yai Canal area in Ayutthaya times was thick with Sa-kae trees, forming dense woods, while the opposite bank was swampy with reeds—ideal for ambushes against careless enemy boats. The term “bang ying ruea” (ambush boats) likely evolved into “Bang Yi Ruea” over time.

Wat Intharam was paired with Wat Ratchakhrue (Bang Yi Ruea Nai). When King Taksin established Thonburi as the capital, he greatly favored this temple. He ordered extensive renovations, expanded its grounds, and elevated it to the highest class of royal temple, using it for major royal religious ceremonies. He donated large tracts of land for temple use, constructed 120 monk residences, restored images, the ordination hall, chedi, viharn, and donated Tripitaka volumes. He visited the temple at least five times for meditation retreats, and it was also the site for royal funeral rites, such as for his mother Queen Theppamat (Nok Iang).

The funeral ceremonies for his mother in B.E. 2318 (1775) were elaborate. A royal crematorium was built over two months, with the royal body transported to the temple on Tuesday, 2nd waning moon of month 6. The cremation took place on Thursday, 4th waning moon, lasting three days and nights, with over 20 traditional performances and 6,000 monks invited. Coinciding with the ceremony, Burmese general Azaewunki besieged Phitsanulok, prompting King Taksin to dedicate merit from the ceremonies to his mother once more the following year.

In B.E. 2319, King Taksin held another grand merit-making ceremony in her honor, gathering troops and support from Lopburi, Nakhon Sawan, Phichit, Phitsanulok, Kamphaeng Phet, Sukhothai, Chainat, Singburi, Ang Thong, Chachoengsao, Ratchaburi, Phetchaburi, and Suphanburi to assist the temple in this great religious celebration.

According to the royal schedule, on Tuesday, the full moon of the first lunar month, Year of the Monkey, B.E. 2319 (1776), following the completion of the royal crematorium and ceremonial grounds, and after the procession of the royal relics (Phra Borommathat) from the royal palace through Wat Moli Lok (Wat Tai Talat) to Bang Yi Khan, before being returned and placed at the pavilion in Wat Intharam, King Taksin commanded that the Central Treasury distribute royal donations to all participants in the ceremony. Men received one salueng, women received one fueang, while Phraya Maha Sena was entrusted with ten chang of silver to be distributed to the poor and beggars throughout both inner and outer city areas. The Sangkakari (religious officials) were also ordered to invite ten thousand monks to the ceremony, with 2,230 monks and 1,738 elder monks and novices recorded.

(The Chronicle of Thonburi by Phan Chan Numat (Choem) notes that these monks were invited regardless of sect or monastery. In the Royal Commentary by King Rama V, he clarified that “offering to ten thousand monks” referred to giving two bundles of rice per monk, not monetary offerings as in the Ayutthaya tradition.)

Antiquities and Monuments Related to King Taksin of Thonburi

Phra Chedi Ku Chat (The Nation-Saving Stupa)

A stupa enshrining the royal relics (Phra Borommathat) of King Taksin, paired with another stupa containing the relics of his queen. These two chedis stand in front of the old ordination hall.The Commemorative Buddha Image of King Taksin

A Buddha image in the posture of Enlightenment (Buddha’s Victory), serving as the principal Buddha image in the old ordination hall. It also houses the royal cremated remains (sarira) of the king.Ayutthaya-style Seated Buddha in Maravijaya posture

This image resides in the small viharn adjacent to the old ubosot and is referred to as the Viharn of King Taksin.Old Ordination Hall (Ubosot)

Originally renovated by King Taksin, it originally had no windows. Later, Chao Khun Phra Thaksin Khanisorn, upon becoming abbot, had the walls cut open to create windows.Viharn housing the royal meditation platform

This structure contains the wooden sleeping platform of King Taksin and a replica statue of the king in meditative posture, housed in the Viharn of King Taksin the Great.New Ordination Hall

Constructed over the site where King Taksin’s royal remains were originally buried.Additional prangs, stupas, and viharns were constructed or restored in periods after King Taksin’s reign. Many have deteriorated significantly, while others are currently under renovation or reconstruction.

(Sanan Silakorn, 1988: pp. 123–125)

13.4 Literature

During the late Ayutthaya period, particularly after the reign of King Borommakot, Thai literature, which once flourished, gradually declined into obscurity once more. Following the fall of Ayutthaya to the Burmese in 1767 (B.E. 2310), the kingdom was left in ruins—its cities razed by fire, and it is highly probable that numerous ancient manuscripts were destroyed in the chaos. However, once King Taksin the Great had successfully restored national unity, Thai literature slowly began to regain its vitality. Yet, the Thonburi era spanned only fifteen years and was primarily devoted to rebuilding the nation; as such, literary production during this period was limited. Nevertheless, the works that remain are of considerable value.

It is widely accepted that peace and stability are the fertile ground for the flourishing of literature. Conversely, in times of war and national crisis, literary expression often withers. The reign of King Taksin was one of turbulence and relentless warfare, as previously mentioned. Yet King Taksin did not allow literature to languish under the weight of these challenges. On the contrary, he actively countered this decline and nurtured its revival. Thus, the Thonburi period unexpectedly became a time of remarkable literary creation.

The literature of the Thonburi era was directly influenced by that of the late Ayutthaya period. Existing works were used as models for composing new poetry. Consequently, Thonburi literature bore great resemblance to its Ayutthayan predecessors. Its defining features include:

All surviving works are written in verse, employing every form of classical Thai prosody, including khlong (โคลง), chan (ฉันท์), kap (กาพย์), klon (กลอน), and rai (ร่าย).

The themes predominantly emphasize religion, Buddhist teachings, moral instruction, royal eulogy, and elements of entertainment and delight.

Each composition typically begins with an invocation or homage, showing reverence to sacred entities or figures. The narrative style favors elaborate description and emotional expression, often prioritizing aesthetic beauty over thematic depth or philosophical insight.

Thai cultural values are clearly embedded throughout, including reverence for monarchy, loyalty to the king, adherence to Buddhism, and preservation of Thai customs and traditions.

(Uthai Chaiyanon, 2002: 8–9)

13.4.1 Who were the poets of the Thonburi period?

Poets of the Thonburi period, besides King Taksin the Great himself, were primarily government officials and senior monks. The notable names recorded include:

Phra Wanrat (Thongyu), who later became a teacher to King Rama II (Phra Buddha Loetla Nabhalai) and eventually left the monkhood to serve as Phra Pojanaphimol.

Phra Phimontham of Wat Pho (Wat Phra Chetuphon), who later served as a teacher to Somdet Phra Maha Samana Chao Krom Phra Poramanuchit Chinorot, and was eventually elevated to Somdet Phra Wanrat.

Phra Rattanamuni (Kaew), who later left monkhood to serve as Phraya Thammapreecha, progenitor of the Raktaprajit family.

Nai Suan Mahadlek, who composed the “Khlong Yor Phra Kiat Somdet Phra Chao Krung Thonburi” in 1771 (B.E. 2314).

Luang Sorawichit (Hon), the chief gatekeeper of Uthai Thani city, who later became Chaophraya Phra Khlang (Hon), Minister of the Fourfold Ministry of Trade under King Rama I. He authored Phetmongkut, based on the Vetala tales (the episode where Vetala tells the riddle about Prince Phetmongkut), and the I-nae Kamchan poem. He passed away in 1805 (B.E. 2348).

Phraya Maha Nuphab (On), who composed the Nirat Guangzhou during his visit to China in 1781 (B.E. 2324). His work holds significant historical value, recording events and observations from his journey. He also composed three long poems.

Phra Bhikkhu In from Nakhon Si Thammarat, who co-authored the Kamchan Krittana Son Nong with Phraya Ratchsuphawadi.

Phraya Ratchsuphawadi, originally the chief of the Suraswadi Department in Ayutthaya, was appointed governor of Nakhon Si Thammarat, though the exact year is unclear. He was regarded as a leading poet during King Borommakot’s reign and lived into the Thonburi period. While serving as governor, he was charged and removed from office in 1765 (B.E. 2308). Later, from 1769 to 1776 (B.E. 2312–2319), he served as minister and royal commissioner of Nakhon Si Thammarat. When Chao Nara Suriyawong took office as governor, Phraya Ratchsuphawadi returned to serve at Ayutthaya.

These poets not only contributed to the literary heritage of the Thonburi period but also reflected the intertwining of state service and cultural creation under the restored Siamese kingdom.

13.4.2 What literary works did King Taksin the Great compose?

King Taksin the Great was more a warrior and liberator than a poet, as his reign was filled with warfare. However, as a farsighted ruler who valued literature, he used his leisure time to compose important literary works, most notably the Ramayana (Ramakien). The surviving portions of his compositions include scenes such as Hanuman entering Nang Wanarin’s chamber, Virun defeating Chamlang, King Maliwarat’s judgment, Thotsakan’s ceremony to burn the divine figure, the spear attack by Kabilpasat, Hanuman tying Thotsakan’s hair to Nang Montha, and releasing the horse Upakarn.

Besides literary works, King Taksin also edited or authored royal documents during his reign—such as royal letters, auspicious writings, proclamations, laws, military strategy manuals, weapon-making treatises, proverbs, royal protocols, and customs.

His Ramayana was inscribed on black folding books in gold script, executed with exquisite care. The colophon on each volume records the writing date as Sunday, waxing moon day 1, lunar month 6, Chula Sakarat 1132, Year of the Tiger (corresponding to 1749 BE/2313 CE), the third year of his reign. Later, court scribes recopied and restored these manuscripts, preserving the original layout but adding their names and restoration dates, such as Sunday, waning moon day 8, lunar month 12, Chula Sakarat 1142 (corresponding to 1759 BE/2323 CE). The restorers’ names and donors are also recorded, though unfortunately the original manuscript has not survived.

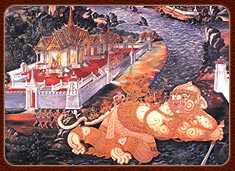

The Ramakien scene showing Hanuman stretching his body as a bridge for King Phra Phrot’s army to cross the great ocean back to Ayutthaya, painted in 1930.

This mural is located in Room 154 of the Phra Rabiang (royal cloister) at Wat Phra Si Rattana Satsadaram (the Temple of the Emerald Buddha) within the Grand Palace, Bangkok.

The artwork was created by the artist Suang Thimudom.

(Source: Rattanakosin Art from Reigns 1 to 8, Volume 1)

The origin of this royal composition stems from when His Majesty led the army to suppress the rebellion of the local rulers in Nakhon Si Thammarat in 1769 (B.E. 2312). At that time, the local lord along with key relatives fled to Thepha, which is in present-day Songkhla Province. The capital’s forces pursued them there.

The memoirs of Princess Narindradevi recount this episode:

“The powerful lord of the city, knowing the army was close, feared the royal might and sent the lord of the city along with his kin, female performers, silver ornaments, royal treasures, and various items as tribute.”

This means that, besides capturing the chief lord as a prisoner, the army also gained female performers as part of the spoils.

While the Thonburi army was trapped by the monsoon in Nakhon Si Thammarat and unable to return to the capital for several months, in the 12th lunar month of that year, King Taksin performed a grand royal ceremony to honor the city’s sacred relics. He also commanded the female performers of the local lord to participate in the festivities. This pleased His Majesty greatly and sparked a strong interest in theatrical arts, which he then nurtured and revived in Thonburi, as reflected later in the development of traditional dance and music.

Just one month after returning from Nakhon Si Thammarat, the King diligently composed the Ramakien drama within only two months, before having to lead another military campaign against the insurgent lord of Phra Fang in Uttaradit in the 6th lunar month of 1770 (B.E. 2313).

Given the short time available for composing such a high literary work, some flaws or less polished parts are understandable. This Ramakien drama is a direct royal composition by King Taksin himself, not adapted or rewritten by other poets (unlike the Ramakien of King Rama I). The work thus reveals His Majesty’s personality and wisdom very clearly.

In the 6th lunar month of 1770, the King also received reports from Uthai Thani and Chainat provinces concerning the misdeeds of the lord of Phra Fang. By the 8th lunar month, he led the royal army to suppress the rebellion. It is believed that King Taksin completed the four acts of the Ramakien during this period but made later revisions, as seen in marginal notes such as “still (bad, impolite) here” or “inserted by the King.”

If the Ramakien was completed before the campaign against Phra Fang and used during the celebratory event after capturing Sawang Khaburi — where, according to the memoirs of Princess Narindradevi, “female performers were brought to celebrate Phra Fang for seven days, then the King proceeded to Phitsanulok for the seven-day celebration of Phra Chinnarat and Phra Chinnasri with female performers” — it is possible that the Ramakien was performed based on King Taksin’s royal composition.

The fact that the King was so devoted to poetry, composing works despite nearly nonstop military duties, inspired contemporary poets to create their own works, even though the country had not yet fully returned to peace.

The purpose behind composing the Ramakien can be summarized as follows:

To continue the royal tradition of promoting literature, with the monarch himself authoring works.

To provide entertainment and joy to the people.

To revive and preserve the important literary work of Ramakien, a significant tradition since the Ayutthaya period.

To select episodes containing moral lessons appropriate to inspire and comfort the people at that time; additionally, to include teachings on Vipassana meditation—an area of deep royal interest—thus encouraging the populace toward mental peace and wellbeing.

To create a royal drama for the royal theater, as customarily, Ramakien was performed. According to the Phan Chan Numas chronicle, when King Taksin led the army to capture Nakhon Si Thammarat in 1769 (B.E. 2312), he brought back the local lord and female performers to establish the royal theater, necessitating the royal composition of a drama script.

The original manuscript’s title page states that King Taksin composed this work in the year Chulasakarat 1132 (B.E. 2313). It is a poetic drama complete with song titles and dance sequences, comprising four parts (four volumes of traditional Thai folded manuscripts).

Part 1: “Phra Mongkut” (The Crown Prince)

This episode, the first royal composition, tells the story of Phra Mongkut and Phra Lob, the sons of Rama and Sita, living in the forest with the sage Valmiki after Sita’s exile. The sage grants them magical arrows. The princes test the arrows, which roar all the way to Ayutthaya. Rama sends the horse Upakara to demonstrate power. Phra Mongkut and Phra Lob ride the horse playfully. Bharata captures Phra Mongkut and offers him to Rama. Phra Lob rescues him, and they escape. The episode ends with Rama raising an army to capture the two princes.

Parts 2, 3, and 4 form a continuous narrative as follows:

Part 2 depicts Hanuman courting Nang Wanarin. The beginning of this episode is missing, so it starts with Hanuman encountering Nang Wanarin in the water. Nang Wanarin is a celestial maiden cursed to guide Hanuman to kill Wirun Cham Bang in order to break her curse. Hanuman marries her, then successfully kills Wirun Cham Bang. Afterwards, he escorts her back to the celestial realm. Thotsakan summons King Maleewarat to come to Lanka to assist him. This part ends as King Maleewarat arrives at the battlefield but refuses to enter Lanka.

Example excerpt from Hanuman courts Nang Wanarin:

“This noble lady, the foremost maiden of the heavens, doubt not — brother shall clarify for sister, just a little request, fair maiden.”

Part 3 is the episode where King Maleewarat acts as an arbiter. With righteous judgment, he summons both plaintiff and defendant, and Nang Sida, to the battlefield and decrees that Thotsakan must return Nang Sida. However, Thotsakan refuses, so King Maleewarat curses him.

Part 4 recounts Thotsakan’s ceremony of sprinkling sand and consecrating the spear “Kabilpasut.” Nang Manto urges Thotsakan to kill Phiphek, who has been prophesying and aiding Rama’s side. Phiphek flees to hide with Phra Lak. Phra Lak then uses the spear Moksak to defend himself. Hanuman must fly to obtain medicine from Mother Hin, who grinds herbs in the naga realm, while her son stays in Lanka. Thotsakan sleeps, enchanted by Hanuman, who breaks the top of the castle to steal Mother Hin’s son. Hanuman then mischievously ties Thotsakan’s hair together with Nang Manto’s, causing Thotsakan to be unable to untie it until the hermit Kobut is summoned to undo the knot.

Example excerpt from Hanuman ties Thotsakan’s hair with Nang Manto’s:

“Having conquered the ascetic practices, the diamond’s worth is but naught,

Both power and magical arts, and mind control combined,

With spiritual discernment, recalling past and future lives,

At that moment all shall perish—no escape at all…”

Episode Thepabut Phali battles Thotsakan

Phali recites the incantation, summoning the power of the demons.

By the blessing of the World Creator, he seizes victory in the fierce demon combat.

Thotsakan, weakened, struggles in the contest of glory,

Hungry and drained, the demon flees to Lanka city.

General characteristics of the Ramakien drama script

The royal authored Ramakien is a poetic drama written in old-style verse of the late Ayutthaya period,

Complete with songs and traditional dance movements for each scene. General characteristics are as follows:

1. Uses simple, everyday words throughout the story, suitable as a play for general audiences, as in the verse:

“The summons calls the heavenly court on high,

By ancient scrolls and sacred laws comply.

Let gods and sages swiftly render right,

Unveiling truth in clear and shining light.”

Thotsakan, the mighty lord, denies the claims,

Disputes the witness and their honored names.

He doubts if Sita came of her own will,

And questions words with skeptic’s wary skill.

The heavenly hosts stand firm, their oath they swear,

No falsehood dwells within the words they bear.

“If I lie and doom myself to endless strife,

Know that I speak the truth, no hint of lies.

Though wrath may rise for your unjust disgrace,

Still truth shines forth and falsehood finds no place.

Sita stands present, pure and undefiled,

No fraud or trickery has been compiled.

In sage’s court, her tale was oft retold,

Returned to reign in splendor, proud and bold.

With rites and bows raised high in sacred rite,

All summoned forth to witness holy light.

Who lifts these tokens gains the sovereign’s prize,

And crowds assemble ‘neath the watching skies.”

The verse style in the royal composition often favors simple, everyday language, At times resembling the folk dramas once performed widely. For example, the scene where Thao Maliwarat hears Thotsakan’s twisted defense,

Claiming the theft of Nang Sida from Phra Ram.

Then heard the sacred Phra Borommaraksa,

The mighty guardian, fierce in righteous cause,

The words of Inthrachit, twisted in deceit,

A crafty speech to mask the truth’s defeat.

“Is this a thing misplaced, or lost in woods,

That one should find it midst the silent woods?

Or has some other seized the lady fair,

And left her far away in wild despair?”

He feared the demon lord might think her spouse,

And cast her off to flee, to hide, to drowse.

Yet surely this suspicion does not hold,

Nor fits the tale so rashly told.

’Tis clear the lady wandered lost and torn,

Her heart confused, her fate forlorn and worn…”

These royal compositions reveal a mind keen and agile, fearless before all, favoring frankness and direct speech, disliking circumlocution, yet delighting in playful wordcraft at times.

In many passages, the language is blunt and straightforward—like a sharp axe cleaving truth—using plain, vernacular words that strike straight to the heart. Especially in the scolding and admonishing scenes, such as when Thao Maleewarat fiercely rebukes Tosakanth for his deceit in the matter of stealing Nang Sida from Phra Ram.

Then rose the just and righteous Tosadharma,

Fierce in wrath, he scolded the demon lord:

“Thou knave, a thief who steals another’s wife,

What aid can madness grant to wicked strife?

When thou hast crept and stolen in the night,

What courage then to show thy brazen face?

If thou should meet her rightful wedded lord,

Would’st thou not cease thine evil, loose thy grip?

Say, was she truly lost amid the wild?

Judge now, and answer for thy deeds defiled…”

Another episode where Thao Maleewarat admonishes and consoles Tosakanth shows not only stern, common words of reprimand and instruction but also weaves in a lighthearted, playful mood about a woman ambushing boats.

Hear now the words my grandsire spoke,

That honor and great glory thou shalt claim;

What care hast thou for fair Sida’s fate?

O mighty demon, heed not her name.

Though she comes from realms divine and bright,

A mortal shadow in her gentle mien,

No crown shall bind thee, nor love’s soft chain,

O demoness, be loosed from longing keen.

One radiant maiden, queen of demon hordes,

Fair as the pearl’s resplendent light,

Enchanting, stirring hearts and minds,

Most lovely maid beyond all sight.

Yet once she was but youthful bloom,

Even aged Manto’s cherished kin,

A foremost poetess of artful craft,

Whose words did dance with playful sin.

If thou dost spurn my counsel wise,

To fiery hell thou surely descend,

For ruin waits on stubborn pride—

What need hast thou for Sida, friend?

2. Not favoring vowel rhymes, still adhering to the common script conventions popular in the Ayutthaya era.

Then spoke the mighty lord, the four-armed Yaksha,

Beholding fair Yida, his heart enraptured by desire.

He brimmed with passion for the maiden’s grace,

Fierce and restless, aflame with fervent longing.

His gaze fixed intently upon her youthful form,

Unable to avert his eyes or let her slip away.

“Oh, Yida, radiant as the moon’s own light,

How wondrously fair, how splendid your beauty!

Though born of sixteen heavenly chambers,

None can match the peerless Yida’s charm.

I, the seer of the tenfold dharma,

Firmly resolved to claim this shining prize.

What care have I for the foul Asura?

Surely, I shall lead him to his doom.”

3. Insert knowledge and insights on Vipassana meditation, showing that while composing the royal literary work, He was already studying or had begun practicing Vipassana. For example, when the hermit Kobutra spoke to Tosakanth, saying

The sage thus spoke of karma’s debt,

That binds the lord of demons’ debt;

To mend the rites with swift dispatch,

And cleanse the stains of coarse disgrace.

Striving to lessen burning flames,

To purge the mind of foul defames,

Entering deep the soul’s insight,

Pure precepts grown in wisdom’s light.

The virtue of true conscience bright,

A weapon strong against the blight—

Thus is the law of noble mind,

The foremost sword to punish crime.

A distinctive and rare quality found uniquely in the Ramakien composed by King Taksin of Thonburi is its frequent emphasis on Dharma and supernatural powers. This reflects His Majesty’s profound wisdom and royal character, showing his deep devotion to the Dhamma and dedicated practice of samatha-vipassana meditation.

When describing the character of Thao Maliwarat, the text often refers to him with lofty titles such as “Phra Thong Tham Thiraj” (Dharma King), “Phra Kopkit Tham” (King who performs Dharma), “Phra Thong Thot Tham Rangsi,” or “Phra Thong Jatusi Yak” (Four-Virtue Yak King), among others. Some passages suggest that the king wove his personal spiritual practices into the narrative. For example, the episode where Lord Shiva sits in meditation and discusses Dharma with a hermit:

“One day she sat,

Upon the radiant throne,

Conversing on noble truths,

With the wise sage Nararotthi.”

This passage reflects King Taksin’s own disposition — a deep enthusiasm for understanding the meanings and teachings of the Dharma. During moments of respite from royal duties, he delighted in engaging in sincere spiritual discussions with monastic dignitaries, and even with religious figures from other faiths, such as French missionaries and Islamic teachers (Tok Kru), as documented in various chronicles and historical records.

The episode where Nang Mantho comforts Thotsakan, who is disheartened because Thao Maliwarat refuses to side with him, skillfully weaves in the teachings of Dharma with great subtlety and depth.

The royal crown of the queen’s brow,

Let not passion’s flame consume,

Though mind may not be flawless,

Defilements still may loom.

Suffering and burning woes arise,

The hindrances that cloud the mind,

Unwholesome seeds entwined within,

Urging unrest to bind.

If sorrow’s cause should yet be found,

And pain in flames descend,

Victory or loss, a path is paved,

By actions one does send.

Yet still, by steadfast effort firm,

Let zeal be deeply sown,

By magic arts and spirits’ sway,

True truth be fully known.

Cleanse the mind from lust and stain,

Till all defilements cease,

Why clutch at what is not thine own—

Let go, and find release.

Especially in the episode where the hermit Phra Khobut teaches Tosakanth, it reveals clearly the profound wisdom of one highly accomplished in the Dharma. The language used is rich with elevated terms of Buddhist teachings. Moreover, it also reflects the presence of miraculous powers attained through diligent spiritual practice.

The venerable sage then spoke of karma’s might,

That it befits the great lord of the yaksha’s plight,

To swiftly amend the rites with care and grace,

To cleanse the stains of sin, and so efface.

Efforts to soothe the burning shame and blame,

To purge the impure from heart and flame,

Within the mind and spirit’s light,

Pure precepts bloom, a noble sight.

The shield of conscience firm and bright,

The first of punishments, just and right.

Then follows second, by renunciation’s way,

A stone that stills all shadows’ sway.

Transcending harm and common strife,

Fire and spear alike hold no life for the yaksha’s life.

All six heavens in the skies above,

How could one kill without knowing death’s true shove?

Do not count the slayer’s might,

For the soul itself suffers endless blight.

What shall be done, none can tell,

Cunning retreats to depths of hell.

Once the renunciation’s power is gained,

The shining gem of wisdom unchained.

Both might and mind’s knowledge combined,

Together with senses and soul entwined.

Recollection spans lives past and to come,

At that point, destruction is wholly done.

No hope remains for body or breath,

Beyond mere calculation of life and death.

Three worlds, three planes cannot entwine,

Swear this truth in a single time.

No demon’s glance can alter fate,

What use then Ram’s valor great?

Through ten directions and the triple sphere,

Fearless is he who wisdom holds dear,

If you desire, learn this here.

This royal composition, His Majesty King Chulalongkorn (Rama V) remarked upon, “These verses laid forth reveal the true heart of the Lord of Thonburi, Clearly showing his faith in valor’s art. And his delight in the practice of meditation and dharma.”

In another instance, His Majesty further noted, “…the passages amended by the Lord of Thonburi chiefly appear

Within the battle scenes and tales of supernatural arts in meditative practice.”

This drama unfolds with concise precision, attuned to the gestures and movements of its performers. As in the scene where Hanuman battles Virunjamphong.

Virunjamphong, struck with sudden dread,

Knew the doom that swiftly spread.

He chanted spells of mystic art,

To slip away and thus depart.

Escaping from the warrior’s blade,

The demon’s shame in darkness laid.

He soared with might and magic grand,

Returning fierce to fight Hanuman’s stand.

Hanuman leapt with valiant force,

Their struggle matched in strength and course.

Virunjamphong struck but could not fell,

Hanuman rose with magic’s spell.

He seized the staff with skill and might,

Virunjamphong sank from sight,

Then rose again to battle fierce,

With rage anew the fight to pierce.

The book “Collection of Exemplary Royal Compositions in Verse” by the Vajirayan Library explains at the end of King Taksin the Great’s royal compositions:

“King Taksin’s compositions for drama are considered difficult. It is said that how he composed was such that the verses were meant to be sung and danced accordingly. Sometimes the original verses were unsingable, which caused the composer to become frustrated.

King Chulalongkorn once recounted in his royal critique book that ‘King Taksin’s compositions differed greatly. It is said that some scenes caused loud outbursts of laughter, almost to the point of madness. Many verses in the scenes involving the monkeys were severely reprimanded, such as:

‘Used by day and also by night,

Sitting on watch by the firelight,

Beating armor, knocking wood,

Could not stay, so fled for good.’

The texts are relatively brief and concise because the King focused on the narrative itself. Therefore, there was no drawn-out or overly elaborate style as found in the Ramakien royal compositions of King Rama I, which are widely known. For example, a certain episode in King Taksin’s composition contains only 146 words, whereas the same episode in King Rama I’s version has 400 words. Comparing printed pages, King Taksin’s Ramakien is only 11 pages, but King Rama I’s version occupies as many as 50 pages.

This shows the King’s quick and straightforward nature; he preferred to speak directly and efficiently to convey the story clearly and promptly, emphasizing substance over style.

The expanded and grander narrative style in King Rama I’s Ramakien likely resulted from poets commissioned to elaborate on each episode, using King Taksin’s composition as a base, merely extending the content.

Hence, the stories are the same, but King Rama I’s version contains many more verses.

There are several parts where King Taksin expressed poetic emotions and aesthetic sensibilities, such as the scene where King Maliwong praises the beauty of Nang Sida, demonstrating an impressive and rich use of descriptive language. This particular composition is quite extensive, and one excerpt will be presented as an example below.

Then stood the lord, the four-armed demon king,

Beholding fair lady Sida, heart aflame with longing.

He harbored secret passion for her,

His fierce desire burning unchecked.

With searching gaze he marked her form,

Unable to turn away his eyes.

“O, fair Sida, radiant and peerless,

No match among the sixteen celestial maidens.

Yet I, who know the tenfold laws,

Still fix my heart upon your grace.

What care have I for yon demon thrall,

That I shall not lead him to his doom?

Alas, O Thotsakan,

Your clan shall surely perish.

Horses, chariots, warriors all shall fall,

Doomed by your love for Sida.

Though I strive to sever desire’s chain,

My spirit burns with restless fire.