King Taksin The Great

Chapter 8: King Taksin’s Coronation at Thonburi

The mural painting depicting King Taksin the Great’s coronation as the ruler of Thonburi.

(Image courtesy of Muang Boran [Ancient City])

Mural painting of King Taksin the Great’s coronation at Thonburi.

(Image from the book Somdet Phra Chao Taksin Maharaj)

8.1 Why did King Taksin the Great not reign in Ayutthaya?

After King Taksin had completed the royal cremation ceremony for King Ekathat, he wished to restore Ayutthaya to its former glory as the capital city. Mounted on the royal elephant, he toured the palace grounds and various parts of the city. He saw that the Grand Palace and its smaller palaces, as well as temples, monasteries, and houses of the city residents, had been extensively destroyed by the enemy. Very few places remained intact, which caused him great sorrow and distress.

On that day, he stayed overnight at the Thong Chai Throne Hall, the royal audience chamber at the rear of the palace. There, King Taksin had a prophetic dream in which the former king came to drive him away, not allowing him to remain. The next morning, he recounted this dream to his officials and declared, “… I am grieved to see our city left desolate and wild. If the former owners still cherish it so, let us instead build a new city at Thonburi …”

Veena Rojanratha (1997: 91) commented on this dream narration, suggesting that it might reflect the high psychological insight of King Taksin. The decision to move the capital from Ayutthaya to Thonburi was justified by many practical reasons at that time.

One of King Taksin’s most admirable qualities was his wisdom as a great leader who listened to the opinions of others, including his subjects. He understood well that the Thai people still revered the royal family of Ayutthaya, and that their hearts remained deeply connected to the old capital. Yet, given the circumstances, the old capital was no longer suitable for governance. Hence, King Taksin sought to gently persuade the people by indirect reasons, demonstrating his exceptional psychological acumen. (Sanun Silakorn, 1988: 13–14)

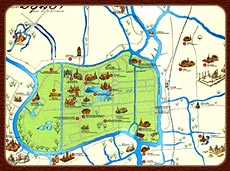

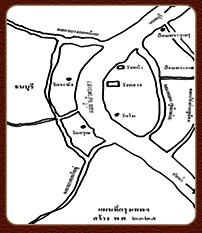

The map of Ayutthaya

(Image sourced from the book Ayutthaya)

Map of the Royal Palace

(Image from the book Ayutthaya)

Reason Why King Taksin Did Not Re-establish the Capital at Ayutthaya

The old capital was vast, with palaces numbering five grand edifices and numerous large temples and monasteries. When the city was ravaged by the Burmese invaders and traitorous elements setting fire, it was left nearly destroyed. King Taksin, having just gathered his forces anew, lacked the necessary manpower and resources to repair and restore such a vast city to become a flourishing capital once again.

Moreover, should enemies approach, the troops available to defend the city’s fortifications would be insufficient, for the populace was scattered and dispersed in all directions, unable to unite in sufficient numbers. (Royal Chronicles of the Old Capital: 70)

Regarding King Taksin’s relocation of the capital from Ayutthaya to Thonburi, His Royal Highness Prince Damrong Rajanubhab commented:

“Upon careful examination of the events as recorded in the Royal Chronicles, it appears that King Taksin’s choice to establish Thonburi as the capital was most suitable and advantageous. Had the late former king come to counsel King Taksin to remain at Ayutthaya, it would have been done with kindness and admonition, to prevent errors born of pride or honor.

Though Ayutthaya held a strong strategic position, surrounded by rivers and well-fortified, King Taksin’s forces were insufficient to defend the city against enemies. At that time, many foes remained, including the Burmese and rival Thai factions who could strike at any time.

Ayutthaya lay on a route easily accessible to enemies by land and water; with inadequate forces, its defense was untenable. Establishing the capital at Thonburi, not far from Ayutthaya, allowed King Taksin to maintain influence as if he were in the old capital but with advantage: Thonburi sat upon deep waterways near the sea, making it difficult for enemies lacking naval strength to assault.

Moreover, Thonburi was smaller and had fortifications suitable to King Taksin’s land and naval forces. If the city could not be held, its proximity to the river mouth allowed retreat by ship to Chanthaburi easily.

This strategic choice also bore political wisdom: Thonburi guarded the river’s mouth, the route through which northern principalities communicated with foreign lands. As Ayutthaya barred northern factions from importing arms, so did Thonburi.

King Taksin himself could secure arms and military equipment more readily.

For these reasons, King Taksin’s establishment of Thonburi as the capital projected power over the northern principalities. This reasoned decision was undoubtedly sound.”

(Tuan Boonyanun, 1970: 67-68)

King Taksin’s forces were too few in number to adequately defend the vast city of Ayutthaya.

Ayutthaya was situated in a location easily accessible to the enemy by both land and water; with insufficient strength to defend it, remaining there would be perilous.

The capital was severely devastated, lacking the manpower and resources necessary to restore it within a short period.

The enemy (the Burmese) were well acquainted with the terrain and entry points to Ayutthaya, and knew the strategic weaknesses of the city, placing the defenders at a great disadvantage.

The supply routes by land from the provincial towns to Ayutthaya were unsafe and vulnerable.

(Sanan Silakorn, 1988: 11)

Wat Phra Si Sanphet before restoration, with a view of the Viharn Phra Mongkhon Bophit seen further beyond.

Photograph dating from World War II, B.E. 2488 (Source: Ayutthaya book).

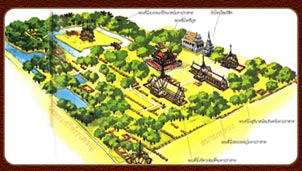

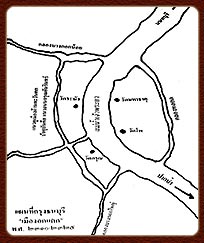

Map of the City of Thonburi

(Image from the book Wiang Wang Fang Thon, Siamese Community)

Wat Phra Si Sanphet after restoration.

(Image from the book Wiang Wang Fang Thon, Siamese Community)

In summary, the reasons for establishing Thonburi as the new capital are as follows:

Thonburi lies in close proximity to the recently reclaimed Ayutthaya (which had been under control of the Burmese with Suki Phra Nayakong commanding at the Phosamton camp), facilitating the defense against any other factions attempting to dominate Ayutthaya from His Majesty.

Thonburi is situated on deep waters near the sea; should enemies advance by land without naval support, it would be difficult for them to succeed in capturing the city.

Thonburi is a city of modest size with terrain suitable to serve as a new capital, adequately defensible by the land and naval forces of His Majesty, and its small scale matches the available population.

Thonburi is fortified on both sides of the river by the Vichaiprasit Fortress (also spelled Vichai Prasit in some records) and the Vichai Yent Fortress, which conveniently guard against naval invasions or sieges. Moreover, Vichaiprasit Fortress was in a condition to be swiftly utilized without extensive repairs, fitting the strength of His Majesty’s forces.

To besiege Thonburi would be extremely difficult if the enemy did not possess a strong naval fleet.

In the event that retaining Thonburi became untenable, the city’s proximity to the river mouth allowed for a strategic retreat by boat back to Chanthaburi or other coastal towns temporarily and conveniently.

Thonburi held strategic importance as it controlled the river mouth, thereby blocking access routes by which northern principalities might trade with foreign powers—similar to the role Ayutthaya once played—thus preventing these northern territories from procuring arms and military supplies from abroad.

Thonburi was also economically vital, being close to the sea and thus convenient for commerce and foreign relations. Furthermore, the surrounding lands—including nearby principalities—comprised fertile plains of clay and mud, well-suited for agriculture, such as the rice fields of Krathum Baen, Nakhon Chai Si, coastal paddies, and the Phaya Thai plains.

8.2 Originally, which city did King Taksin the Great intend to reside in, and why did He change His mind?

At that time, the city of Thonburi consisted only of small forts, and the houses were likely old and dilapidated, without walls. It was probable that He intended to go to a city with stronger fortifications. This matter is mentioned in the Thonburi Royal Chronicles, Phan Chan Nu Mat edition (by Jerm), which states that originally He planned to proceed to the city of Chanthaburi, as follows:

“He beheld the great suffering and calamity of the people — death from famine, robbery, and disease gathered like a mountain. He saw the populace, distressed and starving, with forms as ghastly as hungry ghosts and demons, arousing His deep compassion and weariness of kingship. Though He intended to proceed to the city of Chanthaburi, the monks, Brahmins, ministers, and common folk came together to beseech and entreat His Majesty the King, invoking the Buddha’s wisdom. Perceiving the benefit and necessity for His supreme coronation and enlightenment, He accepted their plea and thus abode at the royal residence in the city of Thonburi.”

The term “phra tamnak” (royal residence) is typically reserved for dwellings befitting His Majesty’s rank and status. However, according to the history of Wat Arun Ratchawararam, when King Taksin descended by barge along the Chao Phraya, he arrived at the temple precincts at dawn. Sensing this auspicious hour, He ordered His royal barge to moor at the landing, then proceeded to venerate the principal stupa at the prang (the original tower stood only eight wa tall). He thereafter spent the night not in a formal royal residence but in the sala kan parian (ordination hall) beneath the shade of the Bodhi tree.

The Royal Throne Bed at Wat Intaram

(Image courtesy of Sara Krung Thonburi book)

The throne within the small vihara of Wat Arun Ratchawararam is adorned with patterns of the zodiac signs, featuring double-layered gold leaf painting, and carved motifs of the Pudtan flower

The royal bed throne is enshrined at the National Museum.

Note: The term “Phra Tamnak” (royal residence) in the Royal Chronicles refers to the sermon hall (Sala Kan Phrien). This is certainly the case because Wat Makok at that time was a small temple, with living quarters and halls far smaller than those of the present day. The sermon hall was comparatively larger and more spacious than other buildings.

Physical evidence remaining today includes His Majesty’s royal throne platform, which is a single plank measuring 17 feet wide and 120 feet long (currently preserved at Wat Arun Ratchawararam). Meanwhile, the royal bed platform (currently at Wat Intaram) is a wooden board 88 centimeters wide, 5 centimeters thick, and 2 meters 487 centimeters long, decorated with carved ivory railings (Suri Phumiphon, 1996: 78).

The reason His Majesty originally intended to go to Chanthaburi was likely because Chanthaburi had city walls, and the town was still prosperous. The people were not yet starving and destitute as lamented in the Royal Chronicles excerpt above. However, if His Majesty had actually gone to Chanthaburi, it would seem as if he abandoned the starving people who were already suffering and dying, because “at that time, there was no one to work the fields; food was scarce, with rice and supplies selling at exorbitant prices — from 3 baht per barrel, to a tamlueng (silver unit), or even 5 baht per barrel.”

Those people then were left with only their bodies, having no money to buy provisions, and they numbered over ten thousand. To leave and flee would mean many would perish without recourse. Moreover, taking the exhausted people far away would not only hasten their demise but also require additional transport means. It is understood that these problems forced him to “remain at the royal residence in Thonburi” and bear the responsibility of caring for the many people. The civil and military officials of Thai-Chinese descent were each granted a barrel of rice, enough for twenty days’ consumption per person (S. Phlaynoi, 2000: 61–62).

8.3 When was King Taksin crowned? What was His royal title?

Thereafter, King Taksin led his troops, family, commoners, and the royal lineage (King Taksin ordered a search to find his relatives and royal kin who had been separated; those found in the city of Lopburi were brought down to Thonburi (Sang Phathnothai, n.d.: 177)). The remaining officials of the old capital who had stayed behind at the Pho Sam Ton camp also migrated to Thonburi. He then elevated the city of Thonburi to become Krung Thonburi Si Maha Samut, establishing it as the capital in the year 2311 BE (1768 CE). The royal palace was constructed at the mouth of the Bangkok Yai canal (currently under the care of the Royal Thai Navy, known as the Old Palace).

Note:

Those interested in matters concerning the royal palace of His Majesty King Taksin the Great may find further information and conduct additional research through the book “Saranuaruu Krung Thonburi Somdet Phra Chao Taksin Maharaj” (Knowledge Series on King Taksin the Great and Thonburi), or by visiting the official website: http://www.wangdermpalace.com/, which is administered by the Foundation for the Preservation of Ancient Monuments in the Old Palace.

As for the precise date on which His Majesty King Taksin ascended the throne, this subject remains a point of considerable debate among historians and scholars, especially with regard to the year and day of the formal Royal Coronation Ceremony (Prapat Daphīsek). According to S. Playnoi (2003: p.122), “His Majesty King Taksin ascended the throne of Thonburi on 28 December 1767 (B.E. 2310).” The Foundation for the Preservation of Ancient Monuments in the Old Palace, in its publication King Taksin the Great (2000: p.30), similarly states that:

“The Royal Accession Ceremony took place on Tuesday, 4th Waning Moon of the 1st Lunar Month, Chula Sakarat 1129, which corresponds to 28 December 1767.” According to Phra Paworanarawitya (1937: p.227), “Upon completing the royal cremation of the late King Ekkathat, King Taksin initially contemplated restoring Ayutthaya to its former glory as the capital. He spent a night at Phra Thi Nang Song Puen (Palace of the Gun Tower), where he dreamt that the monarchs of old appeared and drove him away from the ancient capital. Thus, he abandoned Ayutthaya and founded Thonburi as the new royal city, establishing his palace between Wat Arun Ratchawararam and Wat Molilokkayaram. Thai and Chinese officials then unanimously invited him to ascend the throne in B.E. 2310, at the age of 34.”

The commemorative book marking the inauguration of King Taksin’s equestrian statue in Chanthaburi (1981: pp.41–42) and Veena Rojanarat (1997: p.92) note: “As there exists no definitive historical record specifying the exact date of His Majesty’s accession to the throne, one must deduce from events. After Ayutthaya was reclaimed from the Burmese in the 12th lunar month of B.E. 2310, considerable time would have been required for the royal cremation of King Ekkathat, the release and rehabilitation of Thai nobles and commoners, and the general restoration of order and welfare. The relocation of the capital to Thonburi must have taken place sometime after, thus making it most probable that His Majesty’s coronation occurred in B.E. 2311.”

Furthermore, several primary sources affirm that B.E. 2311 marks the true beginning of His Majesty’s reign. The Astrological Records in the Collected Royal Chronicles, Part 8 state: “In the Year of the Rat, Chula Sakarat 1130 (corresponding to B.E. 2311), on the third day of the waxing moon, at 9:00 AM, there was an earthquake. In that year, Chao Taksin ascended the throne at the age of 34.”

According to the Astrological Chronicle compiled by Phraya Pramoonthanarak, it is recorded:

“(In the reign of the Thonburi Kingdom) the Year of the Rat, Chula Sakarat 1130, Phra Ya Tak…”

Further corroboration is found in the memoirs of the French missionary clergy, who had been present since the late Ayutthaya period under King Ekkathat, continuing through the Thonburi era, and into early Rattanakosin. In Part VI of the Royal Chronicles Collection, Volume 39, a letter by Monsieur Corre addressed to Monsignor Brigot recounts:

“On the 4th of March of this year (1768), I arrived in Bangkok…” and, “Upon my arrival in Bangkok, Phra Ya Tak, the new sovereign, received me graciously…”

In B.E. 2314 (1771), Nai Suan, a royal page, composed a poem extolling the glory of the King of Thonburi, affirming the legitimacy of his enthronement with the following khlōng verse:

“Who dares set himself against the heavens’ will?

All foes fell before his virtuous might.

With lotus throne beneath his royal seat,

He ruled with glory shining in the skies.”

While it can be reasonably concluded that King Taksin ascended the throne and established Thonburi as the new capital in B.E. 2311, due to the absence of any definitive record of the exact date of his coronation, the royal authorities later declared the first recorded day on which His Majesty formally received officials (ออกขุนนาง) as the official commemoration day of his coronation. As described in the Royal Chronicle of Thonburi – Phanchanthanumat (Choem) Version, it states: “On the 3rd day, waxing moon, Month One, Year of the Rat, Samritthisok, during the first night watch, a lunar eclipse was observed.

On the morning of that same day, His Majesty emerged to receive his ministers and addressed them. A merchant named Jin Seng had purchased gold to cast a Buddha image to be loaded aboard a junk. His Majesty, moved by virtuous intent, proclaimed:

He shall uphold equanimity (upekkhā), the Brahmavihāra, for the sake of preserving the Buddhist religion and tending to the welfare of his subjects. Remarkably, the earth trembled for a prolonged moment on that day.”

According to the Fine Arts Department’s Royal Chronicles, Volume 65, cited by Veena Rojanarat (1997: p. 92), this day — “the 3rd day, waxing moon, Month One, Year of the Rat, Samritthisok, Chula Sakarat 1130” corresponds to Tuesday, 28 December 1768 (B.E. 2311). Further evidence appears in Chinese annals referencing King Taksin’s coronation, as well as in additional astrological records that state: “In the Year of the Rat, Chula Sakarat 1130, this year Chao Tak obtained the royal sovereignty at the age of 34.

(It is inferred that His Majesty’s coronation could not have occurred prior to August 1768, as a royal letter was sent during that month to the Qianlong Emperor of Peking, requesting recognition of his enthronement as ruler of Siam. In that letter, King Taksin signed under the royal title of…)”

The name “Kan En Su” corresponds to “Kamphaeng Phet,” which was His Majesty’s royal title before his accession to the throne. (Sang Phatthano-thai, n.d.: 180) According to the book The Royal Biography and Royal Duties of King Taksin of Thonburi (1981: 2), it is stated that “He led troops to suppress various rebellions, successfully reunifying the Siamese kingdom. He was able to capture the Burmese camp at Pho Sam Ton and the city of Thonburi in the twelfth month of the Year of the Pig, B.E. 2310 (1767)… and thereafter performed the coronation ceremony to ascend as sovereign on the third day of the waning moon, Year of the Rat, Chula Sakarat 1130 (B.E. 2311).”

Later, in the Buddhist Era 2311 (1768), His Majesty was crowned king, taking the regnal name “Somdet Phra Borom Ratcha Thi 4” (King Rama IV), although popularly known as “Phra Chao Taksin.” (http://www.wangdermpalace.com/kingtaksin/thai_thegreat.html, 30/11/2004)

N. Na Paknam (1993: 49) recorded: “In Chula Sakarat 1130, the Year of the Rat, he ascended the throne as sovereign king at Thonburi.”

The commemorative book for the opening ceremony of King Taksin’s Royal Monument in Chanthaburi Province (1981: 40) states: “…King Taksin then ordered the populace to relocate and establish the capital at Thonburi from that time forth, and held the coronation ceremony as king on Wednesday, the fourth day of the waning moon, first month, Chula Sakarat 1130, Year of the Rat, Samritthisok—corresponding to December 28, B.E. 2311 (1768)…”

Nattaporn Bunnak (2002: 32), quoting from the “Astrological Chronicles” in the Royal Chronicles Collection, Kanchnaphisek Edition, Vol. 1, Bangkok: Fine Arts Department, page 1, writes: “According to the Royal Chronicles, which corresponds with the astrological chronicles in volume 8 of the collection, it is recorded that King Taksin’s official coronation occurred on Wednesday, the fourth day of the waning moon, first month, Chula Sakarat 1130, Year of the Rat, Samritthisok—corresponding to December 28, B.E. 2311.”

Khajorn Sukphanich (1975: 22–25), in his historical data on the Bangkok era, remarks: “Regarding the history of King Taksin, we can date that His Majesty led about one thousand troops to break through the Burmese siege and flee the capital on January 3, B.E. 2309 (1766), about three months before the fall of Ayutthaya. He captured Chanthaburi on June 14, B.E. 2310 (1767), roughly two months after the capital fell. He then spent approximately five months gathering followers and weapons, and overseeing shipbuilding until sufficient forces were assembled. Subsequently, he led his naval fleet to the river mouth in the twelfth month of the Year of the Rat. The next day, he successfully captured the city of Thonburi…”

As previously mentioned, the exact date of the recapture of Ayutthaya remains unknown; it is only recorded to have occurred in the twelfth month. It has been conventionally fixed as the fifteenth day of the waxing moon, corresponding to November 6, B.E. 2310 (1767), but this is accepted for convenience.

…If we attempt to estimate the time elapsed from when His Majesty King Taksin captured the Pho Sam Ton camp until he established his seat at Thonburi, how long would that period have been? Would it have spanned about a month or so?

Currently, the official date commemorating King Taksin’s coronation is set as December 28, 1768 (B.E. 2311). This means that King Taksin recaptured Ayutthaya on November 6, 1767 (B.E. 2310). The interval between these two dates is therefore over fourteen months.

This disparity seems peculiar—if the coronation date were only a little over a month after the recapture, it would be more plausible. But why then was the coronation set as late as fourteen months afterward? No clear historical evidence has yet been found to explain this delay.

It is said that the date of the coronation is derived from a royal encomium poem composed by Nai Suan Mahadlek, yet the precise stanza containing this information remains unidentified.

Upon examining the book Nai Thongyu Phutthaphat (a representative of Thonburi Province), published along with lunar-to-solar calendar calculations by Phraya Borirak Vetchakan, president of the Astrologers Association of Thailand (Nattaporn Bunnak, 2002: 3), it becomes somewhat clear why this calculation was made: it was based on the year of the fall of the capital and the year of the capture of Chanthaburi being the Year of the Pig (Pi-Kun), while the year of independence was the Year of the Rat (Pi-Chuat).

The person responsible for assigning the lunar dates was not the ecclesiastical authority but an astrologer, which may have influenced the chronology as recorded.

Note:

From document studies, it was found that the source of the calculation by Phraya Borirak Vetchakan is referenced in one book: Somdet Phra Chao Taksin Maharaj by Prayun Pisanaka, published in 1984, page 379.

When the Year of the Pig (Pi-Kun) corresponds to B.E. 2310, the Year of the Rat (Pi-Chuat) must be B.E. 2311. In fact, the events of the fall of the capital, the capture of Chanthaburi, and the siege of the Pho Sam Ton camp all took place in the Year of the Rat in the 5th, 7th, and 12th months respectively. If the Chula Sakarat 1130, Year of the Rat corresponds to B.E. 2311, then the events of the fall of the capital, the capture of Chanthaburi, the recapture of Ayutthaya, and the coronation day should all be in B.E. 2311 as well. This means the coronation date, if also in the Year of the Rat, should be only about a month or so after the recapture of Ayutthaya — not 14 months later. Regarding the royal coronation ceremony, the Foundation for the Conservation of Ancient Monuments in the Former Royal Palace of King Taksin the Great (2000: 17-18) states:

“…The ceremony was likely abbreviated, but the shortened rite still included the essential elements completely. King Taksin seated himself on the Phattharabit throne, accepted the kingship from the Great Royal Brahmin, who respectfully offered the rites according to all coronation scriptures. His royal title was proclaimed as:

‘Phra Si Sanphet Somdet Borom Thammikarajathirat Ramathibodi Boromchakrapat Sri Boworn Ratchabodin Haririndra Thadathabodi Sri Suviboon Khun Rujitra Ritthiramet Saworn Thammikarajadechochai Phrom Thephadi Thep Tri Phuwanathibeth Lokchetsawisut Makutprathetkata Mahaphutthangkura Boromanatbophit Phra Phuttha Chao Yu Hua Na Krung Thep Mahanakhon Boworn Thawarawadi Sri Ayudhya Mahadiloknopharat Ratchathaniburirom Udom Phra Ratcha Nives Mahasathan’ or ‘Somdet Phra Borom Ratcha Thi 4’, but popularly called ‘Phra Chao Taksin.’ However, the government has officially designated December 28 of every year as King Taksin the Great’s Day.”