King Taksin the Great

Chapter 3: The Alaungpaya Dynasty and the Invasion of Thailand

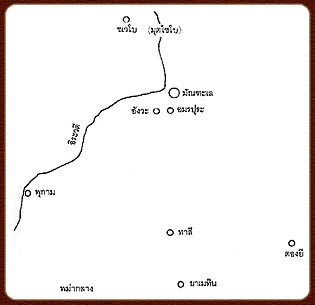

Map of Burma

(From the book “Maharachawong: The Burmese Chronicle,”

excerpted from A Wonderland of Burmese Legends)

The Mandalay Palace

(Image from www.ayeyarwady.com/ Photo-e/old_burma/sh042101.htm, July 20, 2004)

3.1 Who was the Burmese king who led the invasion of Ayutthaya in 1764 (B.E. 2307), and what is his background?

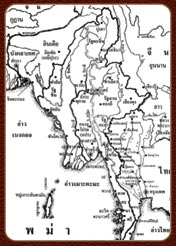

Map of Burma (from the book Maha Rajawangsa: Burmese Chronicles)

The king who led the army that conquered Ayutthaya in 1767 (B.E. 2310) was King Hsinbyushin (B.E. 2306–2319), a ruler from the Alaungpaya Dynasty. This dynasty included a total of 11 monarchs, namely:

Alaungpaya (อลองพญา) – Reign: 1711–1760 (B.E. 2254–2303)

Manglauk or Manglong or Naugdawgyi (มังลอก / มังลอง / นองดอคยี) – Reign: 1760–1763 (B.E. 2303–2306), also spelled Neaudokgyi

Mangra or Sinbyushin or Hsinbyushin (มังระ / สินปยูชิน / ชินบยูชิน) – Reign: 1763–1776 (B.E. 2306–2319), meaning “The White Elephant King.” Also known as Mayedu Meng or Chengpayu Cheng (younger brother of Manglauk). (During his reign, Thailand lost Ayutthaya and then regained it.)

Jingguja or Singu (จิงกูจา / สิงคุสา) – Reign: 1776–1781 (B.E. 2319–2324) (Thailand experienced a 10-year peace period)

Note:

Before passing away, King Alaungpaya declared that the throne would be passed down to all his sons in order of seniority, each taking the throne in turn. However, King Mangra (Mangra) did not follow this royal decree. Instead, he bestowed the throne upon Jingguja (Singu), his royal son, even though King Mangra had four younger brothers: 1) Mangpotakang Abyang, 2) Mangwentakeng Padung, 3)Mangjutakang Pugam, 4)Mangkochiang Takangteng Talae. Jingguja captured and killed Mangpotakang Amien, controlled the other three brothers by placing them in provincial governorships, and found a reason to remove Ase Wunki from his position. Jingguja indulged excessively in alcohol and women. On one occasion, he drank fermented toddy until very drunk. When the chief consort was displeased, Jingguja ordered her to be drowned and demoted Atuan Ngun, her father, to commoner status. Atuan Ngun, feeling resentful, conspired with Chao Takang Padung, assassinated King Jingguja, and then Takang Padung ascended the throne with the royal title King Grownabya Padung Mintakayi. (Source: http://www.worldbuddhism.net/buddhism-history/Burma.html, 14/7/2547)

5. Maung Maung (2324 BE – 2324 BE)

6. Bodawpaya (also called Bodawpaya) (2324 BE – 2362 BE) — started war with Thailand in 2328 BE, known as the Nine Armies War.

Note:

King Bodawpaya is regarded by some as the last great monarch of Burma. Upon ascending the throne, he relocated the capital to Amarapura, a city he commissioned to be built. He later led military campaigns to conquer Manipur, and in 1785 CE (B.E. 2328)—the same year Bangkok was founded—he invaded the Kingdom of Rakhine (Arakan). During this campaign, the Burmese seized a highly revered Buddha image known as the Maha Muni (Mahamuni). This bronze statue, cast in the Maravijaya posture (depicting the Buddha defeating Mara), has a lap width of 5 sok and 1 khuep (traditional Thai units of length). It had been originally cast in 689 B.E., during the reign of King Chandrasurya of Dhannavati, an ancient Arakanese kingdom. In previous centuries, even prominent Burmese kings like Anawrahta had attempted—but failed—to bring the statue to Burma due to various obstacles. This time, however, King Bodawpaya succeeded. To do so, he ordered the statue to be dismantled into three sections for transport.

Ta-khé or Ta-khe (wheeled handcart)

(Image source: http://www.cd-ironworkers.co.uk/misc/trolley2-50.jpg)

This time, the statue was disassembled into three sections and placed onto a ta-khe (also spelled ta-khé), a type of low, wheeled sled or cart traditionally used for transporting heavy objects. In ancient times, these carts were pulled or pushed by people to move large items, such as lifting boats out of the water or transporting them to shipyards (as defined by Viboon Leesuwan, 2003: p.165). The statue was dragged across the mountains into Burma. King Bodawpaya ordered the construction of a grand temple to enshrine the image, and the Mahamuni Buddha has since been revered by the Burmese people more than any other Buddha image in the country—even to this day.

(Source: http://www.worldbuddhism.net/buddhism-history/Burma.html, accessed July 14, 2004)

- 7. Chakkayameng or Bagyidaw (r. 1819–1837 CE)

- 8. Sarek Meng or Tharrawaddy Min (r. 1837–1846 CE)

- 9. Pagan Min (r. 1846–1853 CE)

King Mindon

(Image from the book Thai Thiao Phama — “Thais Travel to Burma”)

An image of the king presiding over royal affairs on the Singhasana Throne (Image from: http://www.4dw.net/royalark/Burma/burma.htm)

- 11. Thibaw, also known as Sīpō (Thebaw), reigned B.E. 2421–2428 (1878–1885) (Mom Rajawongse Saengsom Kasemsri and Mrs. Wimon Pongpipat, History of the Rattanakosin Period, Reigns 1–3 (B.E. 2325–2394), 1980: 37).

Burmese Princesses

King Thibaw and Queen Supayalat

(Image from the book “Burma’s Fall”)

Ladies-in-waiting during King Thibaw’s reign

(Images from the books Burma at War with Siam and Burma’s Fall)

Alungpaya Dynasty

1. Alaungpaya

1711-1760

2. Naugdawgyi

3. Hsinbyushin

6. Bodawpaya

1736 – 1776

1736 – 1776

1745 – 1819

5. Maung Maung

4. Singusa

Insae

1763 -1782

1756 – 1782

1762 – 1808

8. Tharawaddy

1786 – 1846

1786 – 1846

7.Bagyidaw

1784-1846

9. Pagan

Kanuang

10. Mindon

1811-1881

1819-1866

1814 -1878

Limbin

11.Thibaw

Son

+ 1933

1858-1916

Son

Son

Richard Limbin

Thura Limbin

Maung Maung U

Maung Maung Gyi

1902-

Map showing the location of the village Moksobo, now called Shwebo, which was named Ratanasingh, and the city of Ava (Inwa).

(Image from the book The Fall of Ayutthaya)

The Alawngpaya Dynasty

(The term “Alawngpaya” means Bodhisattva — Tuan Boonyayom, 1970: 34)

The Ho Kaew Chronicles recount the story of the Alawngpaya dynasty, established by King Alawngpaya. It states that Mang Aung Jaiya (where “Aung” means victory and “Jaiya” corresponds to “Chaiya”) — called Mong Aung Seya in Burmese — was born into a hunter family north of the city of Ava (Inwa).

Mang Aung Jaiya became the village headman of Shwebo or Muk Cho Bo, which means “Hunter’s Village” or Muk Chai Bo (in Burmese, called Moksobo, later renamed the city of Ratanasingh). It was about 2,000 sen (approximately 97.53 kilometers) from the city of Ava (Inwa), with around 200 households. It is said that Mang Aung Jaiya was a skilled and strong-willed man with great courage. He was knowledgeable in magic spells and military strategies, earning great respect and loyalty from the people. When the Mon rose to power in Ava, they sent officials to collect taxes as usual. Mang Aung Jaiya gathered his followers and fought back, killing all the Mon. Despite multiple attempts by the Mon to suppress him, they were utterly defeated every time.

(Chao Ruptewin, 1985: 638)

In 1714 BE (1671 AD), Mang Aung Jaiya began resisting the Mon by gathering about 40 followers and raiding Mon tax-collecting troops (Janya Prachitromron, 1993: 4). From 1732 BE (1689 AD) onward, Mang Aung Jaiya increasingly achieved victories over the Mon, attracting more Burmese people to join his cause. In the first lunar month of 1733 BE (1690 AD), Mang Aung Jaiya captured the city of Ava (Inwa). Three years later, in 1735 BE (1692 AD), he was honored as the Burmese king with the title Alaw Min Tyaki (Chusiri Chamraman, 1984: 61). He also conquered the city of Dagon, located near the sea, from the Mon (Talaing) and renamed it Rangoon (Yangon). He established the city of Ratanasingh (also known in Thai as Krung Ratanapura-Ava) as the capital. Within two years, he suppressed the northern regions such as Pasem and Syriam and eventually took control of the city of Hongsawadi in 1737 BE (1694 AD). Details are as follows:

King Hongsawadi feared King Alaungpaya and therefore agreed to send his royal daughter named Meikhum—who had previously been engaged to Smingtalapan—as a bride to Alaungpaya. Smingtalapan, feeling resentful, led his followers to leave Hongsawadi. After receiving the princess, Alaungpaya demanded important Mon military officers as hostages. King Hongsawadi refused, which greatly angered Alaungpaya and sparked another war. Ultimately, Hongsawadi fell in 1757 CE (B.E. 2300), and Alaungpaya ordered the city to be burned down. After burning Hongsawadi, Alaungpaya captured a large number of Mon people as prisoners and relocated them to the city of Ava (Ratanasingh). Since then, the Mon nation collapsed and was completely absorbed by the Burmese, marking the end of Mon independence after only seven years.

(Source: http://www.worldbuddhism.net/buddhism-history/Burma.html, July 14, 2004)

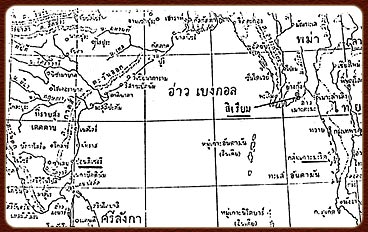

Map showing the location of the city of Syriam

(Image from the book The Fall of Ayutthaya in 1767)

At that time, there was a Mon noble who had once been a commander under Phraya Hongsawadi and was still in hiding. Seeing an opportunity, he led his followers to loot the city of Syriam. The nearby Burmese general learned of this and brought forces to retake the city. The Mon lord, realizing he couldn’t win, gathered his treasures and fled by a French ship, intending to go to Pondicherry. However, the ship was blown by a storm toward the eastern coast and took refuge in the city of Mergui in Thai territory. The Burmese sent a letter to Phraya Tanaw Sri accusing the Mon lord of rebellion and claiming the foreigners helped him escape, requesting that Thailand arrest and hand over both the man and the ship. Thailand replied that the French ship was caught in a storm and had come to Mergui for repairs, and that there was no reason to arrest the ship.

After the repairs were completed, Thailand released the French ship. King Alaungpaya learned of this and was displeased with Thailand but remained silent (Janya Prachitromrun, 1993:4). Meanwhile, Smingtaw fled to Chiang Mai. King Alaungpaya then launched a campaign, advancing into Mon territories further inland, pushing closer to Thai borders. He conquered Mon towns that were once vassals of Ayutthaya, including Tavoy, Mergui, Tanaw Sri, and several smaller towns nearby. Many Mon people fled into Thai territory seeking refuge because the Mon kingdom had collapsed under Burmese domination. The governors of Martaban and other Mon nobles, along with princes of various Tai states, submitted to King Alaungpaya, presenting royal tributes such as horses, fine cloth, and incense. (It’s worth noting that King Alaungpaya tried to weaken the Mon by destroying the city of Pegu to prevent rebels from using it as a stronghold.) He then proceeded to the city of Rangoon (Yangon), which he had founded, before returning to his capital, Ratanasingha.

King Alaungpaya had extraordinary strength beyond ordinary men. After successfully crushing the Mon rebellion, he rested for only one year before brutally marching his army to subdue Manipur. Over 4,000 villagers refused to leave their homes as ordered, so he commanded that all the men in that village be executed. As for the governorship of Manipur, he handed it over to one of the ministers of the fleeing Manipur prince. He also had a stone stele erected in the city center, declaring: “Only heirs of the royal bloodline shall have the right to be princes.” After all that, he returned to his capital city, Ratanasingha.

In 1759 (B.E. 2302), King Alaungpaya led an expedition to Rangoon to perform a dedication ceremony for the Shwedagon Pagoda, which he had commissioned. The army moved both by land and water, with various princes and regional governors in command. Among them, 13 major land forces marched through Toungoo. His second son, Sirithammaracha (known to the Thais as Mangra), commanded a fleet of 300 ships with 10,000 troops. Alaungmintayakyii himself led 24 units totaling 24,000 soldiers and 600 large warships. He appointed Min Kong Naratha as his deputy general and had Portuguese royal guards closely escorting him. The rear guard consisted of 10 units.

Half of the forces, about 5,500 soldiers with 100 large ships, were commanded by his third son, Thado Min Hla Dayaw, the governor of Amyint (called Mangpo by the Thais). The other half was led by his fourth son, Thado Min Saw, the governor of Patung (known as Mangweng in Thai). (Source: Chusiri Jarman, 1984: 62)

Burmese Warships

(Image from the book พม่ารบไทย [Burma at War with Thailand])

3.2 Why did Burma under King Alaungpaya invade Ayutthaya?

After the consecration ceremony of the pavilion at the Shwedagon Pagoda in 1759 (B.E. 2302), King Alaungpaya received news that the Siamese (Thai) had invaded the territory of Tavoy (Dawei) and had seized four Burmese ships. This enraged the king, as he considered it a grave insult to his authority and dignity. Therefore, he resolved to lead a military campaign against Ayutthaya. However, an ominous event occurred—lightning struck the center of his capital seven times. The royal astrologers interpreted this as an ill omen. Furthermore, the direction in which Ayutthaya was located was deemed inauspicious according to King Alaungpaya’s birth chart. Despite these warnings, and objections from his close ministers—who advised that his fortune at that time was unfavorable—the king ignored all counsel and proceeded with the military expedition. The Burmese army advanced through the towns of Martaban (Mottama) and Mawlamyine (Moulmein), then moved southward through the cities of Tavoy (Dawei), Mergui (Myeik), and Tanintharyi (Tenasserim). Burma easily captured these three cities, which even surprised the Burmese, who found the Thai defenses to be unexpectedly weak. King Ekkathat of Ayutthaya dispatched two armies to confront the invasion:

One led by Phra Ya Yommarat, who stationed his troops at Kaeng Tum (believed to be at the upper reaches of the Tanintharyi River in present-day Myanmar), and

Another led by Phra Ya Rattanathibet, who positioned his forces in Kui Buri.

After the Burmese successfully took the three Thai cities, they marched toward Phra Ya Yommarat’s army at Kaeng Tum. Despite minimal effort, the Burmese managed to easily defeat Yommarat’s forces.

Map showing the towns of Mergui and Tenasserim

(Image from the book The Fall of Ayutthaya, Second Time)

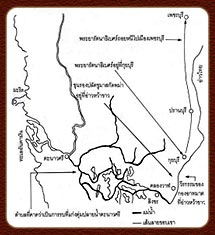

Sketch Map Showing the Battle of the Atamat Army at Ao Wa Khao, 1759 (B.E. 2302)

(Image from the book The Fall of Ayutthaya, Second Time, 1767 (B.E. 2310))

Phraya Rattanathibet, who was stationed in Kui Buri, learned that Phraya Yommarat’s army had been defeated. He therefore dispatched Khun Rong Palat Chu and officials from the Wiset Chai Chan district, along with an execution unit of 400 men, to intercept the Burmese at “Hat Wa Khao,” a coastal area. On the Burmese side, after routing Phraya Yommarat’s army and scattering the troops, they advanced through the Singkhon Pass, emboldened by their earlier victory.

Tangda Mingyi

Kinwun Mingyi (Image from the book Burmese Wars with Thailand: On the Wars Between Thailand and Burma)

Senior Burmese Nobles and Lawyers

(Image from the book Burmese Wars with Thailand: On the Wars Between Thailand and Burma)

Infantry and armored cavalry soldiers of the Konbaung era, followed by spearmen wielding throwing spears

(Image from the book Burma at War: On the Wars Between Thailand and Burma)

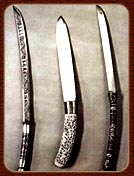

Burmese sword

(Image from the book Burma at War: On the Wars Between

Thailand and Burma)

Prisoners during King Thibaw’s reign

(Image from the book The Fall of Burma)

Image showing the binding and roundup of captives by Burmese soldiers

(Image from the book Maha Yazawin — the Burmese Chronicle)

Khun Rong Palat Chu was a battle-hardened warrior who led a unit of elite soldiers to wait at Hat Wha Khao (White Sand Beach). On one side was overconfidence, and on the other, a thirst for battle. When they clashed, the fight turned bloody. Four hundred Thai soldiers faced 8,000 Burmese troops, fighting from dawn until noon. Burmese bodies piled like logs, but more troops came relentlessly, undeterred by the casualties due to their overwhelming numbers. The Thai soldiers grew exhausted. Eventually, Khun Rong Palat Chu was captured by the Burmese. However, he was invulnerable—swords and spears could not pierce him. Once their commander was captured, the Thai soldiers lost morale. Seizing the moment, the Burmese unleashed their war elephants, which had been standing by. The Thai forces were trampled and routed. When Phraya Rattanatibet received word of the defeat, he panicked and fled with Phraya Yommaraj’s army. The Burmese gained control of Kui Buri, Pranburi, Cha-am, Phetchaburi, and Ratchaburi, all the way to Suphanburi—without much resistance. (Niyom Sukrongpaeng, 1986: pp. 104–105)

Points for Consideration

The Battle at Ratchaburi:

The Thai side reportedly had 20,000 troops, composed of soldiers from Kanchanaburi and Phetchaburi. On the other hand, it was known only that the Burmese commander of the unit was Mang Kong Naratha. The exact size of the Burmese force remains uncertain. Initially, during the campaigns against Myeik (Mergui) and Tenasserim, they had around 8,000 troops. However, after King Alaungpaya ordered a restructuring of the army, it is unclear whether more troops were added to this forward-advancing unit.

If the number remained unchanged, it is regrettable that 20,000 Thai troops failed to hold off 8,000 Burmese troops plus reinforcements. A more determined resistance might have delayed the Burmese advance, giving the rear forces more time to prepare.Nature of the Engagement:

The battle at Ratchaburi appears to have involved mainly garrison or outpost forces. It likely should not have escalated into a full-scale decisive engagement. Thai forces should have preserved their strength by avoiding fierce battles and retreating in stages toward the main army to later regroup for a major confrontation.King Uthumphon’s Preparations:

Following the fall of Ratchaburi, King Uthumphon’s response was extremely rushed. Certain tasks—such as constructing a second layer of city walls and fortifications—required significant time and could not be completed quickly. The only viable strategy at that point was to build while defending simultaneously.The Burmese Halt at Suphanburi:

The Burmese pause at Suphanburi, during which they waited for reinforcements and regrouped, inadvertently benefited the Thais. This delay gave Ayutthaya more time and space to maneuver—both of which were absolutely critical for its defense.

Note: The area between Suphanburi and Phanom Mok is not to scale.

This is a schematic map illustrating the battle at Ratchaburi as the Burmese pursued the Thai forces, as well as the deployment of Thai troops defending Suphanburi and the battle at Thung Talan.

(Image from the book: The Fall of Ayutthaya, the Second Time, B.E. 2310)

The Battle at Thung Talan (Suphanburi, B.E. 2302 / 1759 CE)

Situation:

After King Alaungpaya reached Suphanburi, he paused for several days to regroup and wait for reinforcements, as he deemed his current forces insufficient to attack Ayutthaya directly.

The Battle:

Once King Alaungpaya had gathered enough troops, he resumed the advance. Burmese forces then clashed with the army led by Chao Phraya Mahasena, who had positioned troops to block them along the banks of the Chakkarat River in the Thung Talan paddy fields. Burmese commanders Mang Khong Naratha and Prince Mangra led their troops in an assault on the Thai camps. Fighting was fierce. The Thai army used the river as a natural barrier, and as the Burmese crossed it to attack, they suffered heavy casualties under Thai fire and were forced to retreat. However, when King Alaungpaya’s main force arrived—now vastly outnumbering the Thai side—they executed a flanking maneuver and surrounded the Thai army. The Thai forces were overwhelmed and routed.

Chao Phraya Mahasena was killed in action. Chao Phraya Yommarat was wounded and later died in Ayutthaya. Only a few commanders survived, including Phraya Rattanatibet and Phraya Ratchabangsan. Most of the Thai soldiers were slain in the battle.

The battle at Thung Talan, which occurred quite close to Ayutthaya, can be compared to a forward defense operation that was perhaps extended too far. The fighting was not expected to escalate into a decisive defeat, but the presence of a river as a natural barrier likely encouraged Thai forces to engage fully in order to inflict maximum damage on the Burmese before they could reach the main stronghold of Ayutthaya. After the Burmese, under King Alaungpaya, successfully overran the Thai camp at Thung Talan, they advanced to Ayutthaya, arriving on April 11, 1760—marking the 22nd war between Burma and Siam.

Burmese Troop Deployment

The main army was stationed at Ban Kum, north of the capital, while the vanguard, led by Prince Mangra and Mang Khong Naratha, established their position at Pho Sam Ton.

Establishment of a Base of Operations

In this campaign, Luang Abhai Pipat, a Chinese nobleman, led about 2,000 Chinese volunteers from Ban Naikai to offer their services in attacking the enemy camp at Pho Sam Ton. In response, Chao Muen Thipsena, Deputy Chief of Police, was ordered to lead a supporting force of 1,000 men.

The Battle

Before the Chinese troops could establish a fortified camp, the Burmese crossed the Pho Sam Ton river and attacked, routing the Chinese forces. Chao Muen Thipsena’s reserve unit, which was still stationed at Wat Thalayya in the Thung Phaniat area, was unable to provide timely support. Upon witnessing the Burmese pursuing and slaughtering the Chinese, the reserve forces also panicked and fled. This battle resulted in heavy casualties for both the Thai and Chinese. Seeing the advantage, Prince Mangra swiftly moved in and set up camp at Thung Phaniat, while Mang Khong Naratha advanced as a forward guard to Wat Sam Wihan. After this, there were no further records of the Thai side engaging the Burmese in open battle. The focus shifted to defending the capital, while external areas were left to Burmese control.

Consideration

The battle at Pho Sam Ton represented an effort by the Thai forces to establish an operational base and launch quick strikes to both disrupt the enemy and gather intelligence. However, the operation failed because the Burmese preempted them, launching an attack before the Thai could organize and carry out their planned maneuvers.

The Burmese army under King Alaungpaya besieged Ayutthaya in April 1760, early in the reign of King Ekatat, who lacked military experience. The king had to rely on previously capable generals to defend the city and sent a commander who had been inactive for a long time to face the enemy. Unable to resist the Burmese forces effectively, they retreated to defend within Ayutthaya itself. The Thai people and officials petitioned to summon Somdet Phra Utumphon, who was then a monk, to take command of the Thai army, after which the resistance improved significantly.

The Burmese assault on Ayutthaya (Ayutthaya, 1760) began on April 23, 1760, when about 2,000 Burmese soldiers moved down to the rear canal banks (the canal referring to the river just south of the city near the mouth of Khlong Takhian). At that time, many merchant boats fled from the northern side and gathered together at the rear canal, including royal barges, ceremonial boats, and fleet vessels kept in the northern royal dockyard. The Burmese killed many people—men, women, and children—and burned all the boats gathered at the rear canal.

A schematic map showing the battle at Pho Sam Ton

(Image from the book “The Fall of Ayutthaya, Second Fall, 1767”)

By April 29, 1760, the Burmese had positioned their artillery at Wat Ratchaphrue and Wat Kasat on the western side, firing into the city of Ayutthaya. King Utumphon rode an elephant to personally command the defense, ordering the Thai forces to return fire with their own cannons. The battle of artillery fire continued until evening, after which the Burmese retreated. On April 30, 1760, the Burmese placed their cannons at Wat Na Phra Meru and Wat Hasdawas, bombarding the royal palace both day and night, with cannonballs even striking and breaking the pinnacle of the Phra Thinang Suriyachan Amarin throne hall.

Cannons Stationed at Mandalay

(Image sourced from Burma at War with Siam: Concerning the Warfare between Thailand and Burma)

On the day the Burmese fired upon the royal palace, King Alaungpaya personally took command and ignited the cannon himself. Unfortunately, the cannon exploded, severely injuring him. He fell gravely ill that day. (According to the article “Buddhism,” regarding the cause of King Alaungpaya’s death, it is mentioned that Alaungpaya, seeing the approach of the flood season, sent a royal letter into the city stating, “I am a supreme Bodhisattva wishing to visit and circumambulate the city of Ayutthaya…”)

To bestow blessings upon the entire Thai nation, akin to the Lord Buddha’s own visit to Kapilavastu, the Thai sent a response stating: ‘In this era, four Buddhas have already preached the Dharma. The future Buddha, Maitreya, currently resides in the Tushita Heaven. Moreover, it has been less than 5,000 years since the passing of the Buddha Shakyamuni. Therefore, the Thai cannot accept any Bodhisattva who falsely infiltrates with claims of supernatural abilities, lest they suffer the severe punishments of the Avici hell.’

Alaungpaya was furious upon receiving that missive and personally attended the cannon emplacement to fire his artillery. However, the powder charge was excessive and the gun burst, wounding him and forcing an immediate withdrawal of his forces. En route northward, Alaungpaya succumbed to his injuries at Mögo Kalok in the Tak district, although some Burmese chronicles attribute his death to a preexisting elephantiasis lesion (Chao Rupthewin, 1985: 644).

The Burmese retreat was precipitate: they abandoned dozens of heavy guns, burying them in the royal camp. Thai troops, unaware initially of Alaungpaya’s incapacitation and suspecting a feigned withdrawal, did not pursue. Once it became clear that the Burmese had truly broken camp, Prince Utumphon ordered Phraya Yommarat and Phraya Siharajdechochai to lead a pursuit; they reached Tak too late to engage the enemy. By then, Burmese forces had already departed in good order and were beyond effective reach.

The sequence of events in the war during B.E. 2302–2303

Date | Month | Year (B.E.) | Event |

2302 | Alaungpaya ordered Mangra to lead the army to attack the cities of Tenasserim and Mergui. At the end of this year, Alaungpaya sent forces to invade Thailand. | ||

11 | April | 2303 | The Burmese army advanced to Ayutthaya. |

23 | April | 2303 | 2,000 Burmese soldiers moved to attack the rear gates on both sides. |

29 | April | 2303 | The Burmese positioned cannons at Wat Ratchapli and Wat Kasat, firing into the city. |

30 | April | 2303 | The Burmese placed cannons at Wat Na Phra Meru and Wat Hastarawas, firing at the palace. Alaungpaya personally commanded the ignition of the cannons, but a cannon exploded and severely injured him. |

Simplified Map Showing the Attack on Ayutthaya in 1760 (B.E. 2303)

(Image from the book “The Fall of Ayutthaya, Second Time, B.E. 2310”)

2. Preparations

King Alaungpaya’s sudden decision led to a lack of key preparations, which traditionally took nearly a year. This resulted in several major challenges:2.1 Manpower

The force that attacked Tavoy and then Mergui and Tenasserim had only about 8,000 troops. The size of the main army and two additional reinforcements is unclear—possibly smaller due to the haste, or larger due to Burmese control of nearby cities.2.2 Force Composition

Naval Forces: Needed to counter the Thai navy, as Ayutthaya was surrounded by water—a tactic used in past campaigns.

Artillery: Long-range cannons were essential for attacking the capital. The Burmese had such artillery, likely brought with the second wave. However, the Thai forces responded with heavy counter-fire during the siege.

2.3 Logistics and Supply

In particular, the provision of food supplies had not been properly prepared for a prolonged siege on Ayutthaya. However, given that Burma was frequently at war during this period, it is possible that some stockpiles had already been set aside and were thus used temporarily. Historical records do not provide detailed accounts of these logistical arrangements, so this issue is raised here merely as an important point for consideration.

Artillery soldiers (A.D. 1879)

The image depicts artillery mounted on elephants, representing an ancient warfare technique dating back to the reign of King Bayinnaung.

(Image from the book Burma at War with Thailand: Concerning the Wars Between Thailand and Burma)

- 3. The Offensive Attack

Although Burma had not undertaken extensive preparations in advance, neither had Siam. However, Burma held a strategic advantage in that its forces were already experienced in warfare and had engaged in frequent military operations. This familiarity allowed them to act swiftly and take the initiative. Thus, Burma’s actions can be characterized as a rapid offensive. When King Alaungpaya decided to invade Siam, his vanguard forces were already able to advance through the Singkhon Pass without delay—not as a preparatory move, but as part of an active offensive. In effect, Burma compensated for its lack of thorough preparation through the decisive use of a surprise attack.

Infantry procession of the Burmese army (B.E. 2422 / 1879)

(Image from the book Burma at War with Thailand: Concerning the Wars Between Thailand and Burma)

Burmese cavalry soldiers wielding spears

(Image from the book Burma at War with Thailand: Concerning the Wars Between Thailand and Burma)

- 4. Thai Intelligence Operations

Although Thai intelligence efforts caused some confusion and operational errors—leading to troop exhaustion and delays—they nevertheless resulted in engagements such as the clash at Kaeng Tum, near the mouth of the Tanintharyi River, and the battle at Ao Wa Khao, north of present-day Prachuap Khiri Khan. This area was geographically constrained, with a narrow coastal plain and mountainous terrain extending inland to the Banthat Range. Additional resistance occurred at Ratchaburi, a key frontier city. These actions demonstrated that Thailand did attempt to delay and defend territory in accordance with existing strategic plans. In reality, the effectiveness of both strategic and tactical intelligence was limited—partly due to Burma’s surprise offensive. Still, Thai military units managed to carry out area defense operations that aligned with national defense strategies, though under increasingly time-constrained conditions.

ChatGPT said:

5. Enemy Movement Routes

5.1 Singkhon Pass

This was the route by which the first Burmese units actually entered Siamese territory. The likely rationale was logistical efficiency: at the time of the decision to invade, the Burmese troops stationed in Myeik (Mergui) were only about 135 kilometers from Ban Singkhon in a straight line. Therefore, it was considered more practical to conserve manpower by taking the nearest route, even if it meant revealing their intentions prematurely. It was deemed preferable to a longer and more exhausting march to the Three Pagodas Pass. The hardship of a 5–6 day journey through difficult terrain was seen as an acceptable trade-off. However, this rapid advance also meant that Siam had very little time to organize a proper defense.

The Three Pagodas Pass

(Image from Burma at War with Thailand: Concerning the Wars Between Thailand and Burma)

5.2 Three Pagodas Pass Even though intelligence reports indicated enemy movement without confirmed sightings, this route was still strategically plausible. It aligns with expectations that two additional Burmese armies—whose exact size and movement were not clearly recorded in historical documents—would follow through this pass. Given its significance as a traditional invasion route into central Siam, it was reasonable to anticipate further Burmese advances via this channel.

5.3 Mae Lamao Pass It remains unclear how strategic intelligence from the Kamphaeng Phet region was obtained. Despite reports indicating that another Burmese army would advance through this pass, the information caused considerable confusion. This uncertainty led to delays and unnecessary dispersal of Siamese resources, undermining defensive coordination and costing valuable time and manpower.

6. Siam’s Preparations After the fall of the frontier town of Ratchaburi, Prince Uthumphon emerged from monastic life to lead the defense of the capital. His preparations for Ayutthaya’s protection were swift and urgent. These included conscripting civilians, reinforcing fortifications, and dispatching forces to delay the Burmese advance at Suphanburi. Despite the limited time, notable battles were fought—first at Thung Talan, and more fiercely at Pho Sam Ton. Nevertheless, the Burmese forces eventually reached the outskirts of Ayutthaya. Given the short window available, Uthumphon could only implement partial defensive measures, making a last-ditch effort to stall the invasion as best as circumstances allowed.

The Three Pagodas Pass

(Image from www.thaicabincrew.com/html/memory21.htm, July 20, 2004)

7. Burmese Operations

After the battle at Pho Sam Ton, the Burmese forces advanced to surround the city of Ayutthaya. It is believed that they approached primarily from the north rather than encircling the city entirely. Nevertheless, they initiated military actions in other strategic directions as well.

7.1 Deployment to the Rear Moat on Both Banks

The Burmese likely aimed to destroy Siamese boats to prevent the transport of additional food supplies into the city. By cutting off access to provisions, they hoped to force a quicker conclusion to the conflict.7.2 Burmese Artillery Bombardment of the Capital

The Burmese conducted heavy artillery bombardment on the city, with the Siamese returning fire in kind. In the following days, the Burmese intensified their attacks, firing continuously both day and night. Their goal appeared to be to inflict psychological and physical damage sufficient to compel Siam to surrender, rather than relying on a prolonged siege to starve the defenders into submission—particularly since the Burmese themselves likely lacked sufficient provisions for a drawn-out campaign.However, the operation came to an abrupt end when one of the Burmese cannons exploded, seriously injuring King Alaungpaya. The very next day, the Burmese forces began their withdrawal. Thus, the siege ended in total failure for the Burmese.

8. The Burmese forces reached Ayutthaya on April 11, 1760 (B.E. 2303) and withdrew on May 1, 1760, remaining near the capital for a total of 20 days. They were unable to defeat the Thais or maintain a siege long enough to starve the city into surrender.

9. A final question for consideration is whether the Burmese would have withdrawn if King Alaungpaya had not been seriously injured.

D.G. Hall, in A History of Southeast Asia Vol. 1 (p. 562), summarizes the reasons for the Burmese retreat as follows:

“… King Alaungpaya invaded Thailand and laid siege to the capital, claiming that his cause was to demand the surrender of Mon rebels who had sought refuge in Thailand. However, his true aim was to restore Burmese glory to the level achieved under King Bayinnaung. Thai sources insist that even if Alaungpaya had not been gravely wounded, he would have still been compelled to withdraw, as the Burmese were unprepared for a prolonged war. Therefore, he resolved to return before the rainy season of 1760. Alaungpaya’s death merely delayed the next Burmese invasion of Thailand by two to three years.”10. The Burmese retreat is regrettably marked by the Thai failure to pursue them.

The Thais feared falling into a Burmese trap and thus missed an opportunity to press their advantage. The Burmese retreat was hurried, likely taking the shortest route via the Three Pagodas Pass. This route, however, was a difficult mountainous path beyond Kanchanaburi, whereas the alternative route through Tak province and Mae Lamao Pass was more fertile and less ravaged, potentially providing food supplies. If the Burmese indeed chose the latter route to replenish their provisions, this suggests their forces were already facing serious supply shortages.11. This war saw the Burmese initiating a campaign without adequate preparation, taking a longer and more arduous route.

Had they chosen to use the Three Pagodas Pass instead of the Singkhon Pass, their vanguard would have reached Ayutthaya more quickly, allowing both sides less time to prepare defenses. Although the Burmese strike force arrived earlier as the aggressor, the overall Burmese troop strength was limited. It remains uncertain whether the Thais, under normal circumstances, could have successfully countered such a rapid offensive.

(Janya Prachitromron, 1993: 24-39)

According to the Thai Royal Chronicles, during the siege of Ayutthaya, King Alaungpaya personally fired a cannon, which exploded and seriously injured him. He was forced to retreat north and later died near Mueang Rahaeng (Tak) at the age of 46. His son, Prince Hsinbyushin (Mangra), kept the death secret to avoid panic in the army. His remains were cremated in the Burmese capital, and his ashes enshrined in Shwebo. In contrast, the Hor Kaeo Chronicle states that the king fell ill with a large abscess (possibly an infected boil) during a 5-day siege and died at Motklok near Martaban in May 1760 at age 45. Burmese historian Maung Tin Aung supported the Thai version. Western scholar D.G.E. Hall also noted the Burmese chronicles often favored Burmese perspectives, and he confirmed that the invasion was initiated by Burma—not Siam. After Alaungpaya’s death, his eldest son Naungdawgyi ruled briefly (1760–1763) amid internal rebellions. He was succeeded by his brother Hsinbyushin (Mangra), a skilled military leader, praised as the equal of King Bayinnaung. Mangra had fought alongside his father from a young age and led major campaigns to control southern Mon territories.

3.3What were King Hsinbyushin of Burma’s reasons for launching an attack on Ayutthaya?

In 1763 CE (B.E. 2306), King Hsinbyushin—also known as Sinbyushin or Siridhammaraja—ascended the Burmese throne. He was the second son of King Alaungpaya, succeeding his elder brother, King Naungdawgyi (Manglok). Hsinbyushin was a monarch known for his strong militaristic inclinations. He officially took the throne in December 1763, continuing the legacy of the Konbaung dynasty with a focus on warfare and territorial expansion.

The Burmese Military Formation: “Vishaka Phayuha” was arranged in the shape of a scorpion claw formation (pincer-like).

(Illustration from the book “Burma Fights Siam: On the History of Warfare Between Thailand and Burma”)

Although King Hsinbyushin had not yet undergone a formal coronation ceremony, he had already begun planning a military campaign against Ayutthaya. As part of his preparations, he appointed Abaikkhamani as Ne Myo Thihapate, governor of Chiang Mai, with the task of mobilizing able-bodied men from the northern Thai-Lanna and Lan Xang regions to form an army aimed at attacking Ayutthaya. Ne Myo Thihapate departed from Rattanasinkha (the Burmese capital at the time) in March 1763 (B.E. 2306), leading an initial force of 20,000 troops, 100 war elephants, and 1,000 horses. At the same time, King Hsinbyushin appointed another Burmese general, Maha Nawrahta, to lead an equally sized army southward to invade the coastal cities of Tavoy (Dawei), Mergui (Myeik), and Tanintharyi. His army was ordered to advance inland through Ratchaburi, then capture Phetchaburi, Chaiya, Chumphon, Kanchanaburi, and Suphanburi. Once these strategic locations were secured, Maha Nawrahta’s troops were instructed to wait in Suphanburi for further royal orders before proceeding.

The strategy of launching a two-pronged invasion—a classic pincer movement—was initiated by King Hsinbyushin of Ava nearly 200 years before Hitler employed a similar tactic in modern warfare.

(Khachon Sukhapanich, 2002: 263)

In 1764 (B.E. 2307), King Hsinbyushin led a successful military campaign against Manipur, capturing the city in December. The following year, he relocated people from Manipur back to Ava, which he had designated as the new capital of the Konbaung dynasty. The official move into Ava took place in 1765 (B.E. 2308). King Hsinbyushin also renovated Ava’s city gates, naming them after various regional cities. For example, the eastern gates were named after Chiang Mai, Martaban, and Mogaung, while the southern gates bore names such as Kengma, Hanthawaddy (or Pegu), and Onnyong (present-day Hsipaw).

The western gates of Ava were named after Vientiane, Lan Xang, and Kengtung, while the northern gates were named after Tenasserim and Ayutthaya. The city’s residential areas were divided by ethnicity: Indian merchants lived in one quarter, Chinese in another, Christians in a separate district, and there were also captives from Thailand and Manipur. The royal palace was fortified like an inner city, surrounded by walls, forts, and moats. King Hsinbyushin’s policy aimed to expand his empire, following the footsteps of King Bayinnaung, whose goal was to conquer Ayutthaya.

According to the Burmese historian Maung Tin Aung,

“The objective of Hsinbyushin to subdue Ayutthaya was well known among the Thai, who could not remain silent upon learning of his accession to the Burmese throne…” The Foundation for the Conservation of the Old Palace (2543: 32) noted that Hsinbyushin had suppressed rebellions within Burmese territories and realized that Ayutthaya’s interference in Burmese vassal states (traditionally under the Konbaung dynasty’s influence) encouraged rebellion. Therefore, it was necessary to destroy the Ayutthaya Kingdom completely so it could no longer support Burma’s rebellious provinces. Historian Wiset Chaisri (2541: 250) wrote in Thai-Thai: The Fall of Ayutthaya that one reason for the invasion was Ayutthaya’s failure to send tribute to King Alaungpaya as promised. This evidence comes from letters of missionaries residing in Ava and Rangoon during the reign of King Bodawpaya (1783–1806) and aligns with the Konbaung Chronicle. It states that during Alaungpaya’s siege of Ayutthaya, the Thai pursued a delaying strategy to expose the Burmese army to the flood season by sending envoys pretending to surrender and offer tribute.

During the final campaign of King Alaungpaya, founder of the Konbaung dynasty, the Burmese forces withdrew from the siege of Ayutthaya due to the onset of the flood season and the king’s declining health. His successor, King Hsinbyushin, fully understood these circumstances. Although the withdrawal appeared as a Burmese defeat, it was largely due to natural impediments and strategic considerations. The death of Alaungpaya further galvanized Hsinbyushin’s resolve to decisively subjugate Ayutthaya and assert his claim as a universal monarch (Chakravartin), a concept deeply entrenched in Burmese royal ideology.

The Burmese campaign against Ayutthaya in 1764 CE (B.E. 2307) was not prompted by perceived weakness of the Siamese kingdom, which remained a resilient polity and regional power. A critical factor was territorial disputes over the Tenasserim coast: Mergui and Tenasserim were under Siamese influence, while Tavoy was held by Burma. During the dynastic transition from King Manglauk to Hsinbyushin, the Tavoy governor, Huy Tongja, rebelled against Burmese rule and sought allegiance by sending tribute to Ayutthaya. Consequently, the Burmese launched a military expedition to reassert control over Tavoy. Huy Tongja fled toward Mergui, pursued by Burmese forces through the strategic Singkhon Pass (modern Prachuap Khiri Khan), leading to engagements at Kamnoet Noppakhun (Bang Saphan), Khlong Wan, Kui Buri, and Pran. At Phetchaburi, Burmese troops encountered the Siamese defense under Phraya Taksin and Phraya Phiphatkos, resulting in a Burmese retreat. Following the demise of Phraya Kamphaeng Phet, King Ekathat appointed Phraya Taksin as the new governor of Kamphaeng Phet, though he remained based in Ayutthaya. The Burmese incursion into southern Siam was limited to raiding parties that withdrew after encountering organized Siamese resistance. Historian Wiset Chaisri notes that the Singkhon Pass was a novel invasion route initiated during Alaungpaya’s siege of Ayutthaya, leveraging Burmese naval logistics from Rangoon and Martaban to Tavoy. Traditionally, Burmese military campaigns against Ayutthaya utilized two primary invasion corridors: one from the north via Chiang Mai or the Mae Lamao Pass near Tak, and the other from the west via the Three Pagodas Pass.

3.4 Who were the two Burmese generals during King Hsinbyushin’s reign who led the invasion of Siam? How did they conduct their military campaign?

In 1765 (B.E. 2308), King Hsinbyushin of Burma dispatched two principal generals, Maha Nawrahta and Nemyo Thihapate, to lead military campaigns on two fronts: the northern and southern routes. This strategy is detailed in the Konbaung Chronicles as follows:

Preparation of the Burmese Military Forces (Konbaung Dynasty) (B.E. 2307 / 1764-1765)

According to the Royal Konbaung Chronicles, King Hsinbyushin had long planned the campaign to attack the Ayutthaya Kingdom in advance. Initially, the King ordered the preparation of 27 military regiments, consisting of 100 war elephants, 1,000 horses, and 20,000 soldiers.

Commander Nemyo Sithu

Deputy Commanders: Kyawdin Thihgathu and Tuyin Yamagyaw

Movement: The entire force departed from Ava (Inwa) in March B.E. 2307 (1764).

Mission: To suppress the Lanna rebellion, invade Lan Xang, and advance toward Ayutthaya. After Commander Nemyo Sithu had consolidated forces from various Shan principalities, suppressed the Lanna rebellion, and captured Luang Prabang, his army increased to approximately 40,000 troops (according to the Ava chronicles, around 5,000 troops) (Sunet Chutintharanon, 1998: 22). King Hsinbyushin perceived that Nemyo Sithu’s army moving alone via Chiang Mai was insufficient to conquer Ayutthaya. Therefore, he organized another army force with the following strength:

100 war elephants, 1,000 horses, and 20,000 soldiers.

- Commander Mang Maha Noratha

Deputy Commanders: Neimyou Gunaye and Tuyin Yanaungyaw

Movement: This army force advanced to join another contingent recruited from the cities of Hanthawaddy (Hongsawadi), Martaban (Mottama), Tenasserim (Tanintharyi), Mergui (Myeik), and Tavoy (Dawei), amassing a total strength of approximately 30,000 troops. The entire force departed from Tavoy on September 25, B.E. 2308 (1765).

Mission: To invade the target cities of Phetchaburi, Ratchaburi, Suphanburi, Kanchanaburi, Sai Yok, and Swa Npong, before advancing toward Ayutthaya.

Considerations

According to Burmese sources, King Hsinbyushin (Maha Mingalar Hsinbyushin) had long prepared to attack Ayutthaya; however, the Thai side was unaware of this. Even merchants who traveled back and forth did not receive any news. Upon reflection, the Thai intelligence was somewhat lacking. Considering the actual situation at the time, it is possible that the Thais knew the Burmese were preparing their forces but did not know against whom they would fight, since the Burmese were continuously engaged in conflicts. Furthermore, the army under Nemyo Sithu first conducted operations in Lan Na and Lan Xang before advancing toward Ayutthaya. This explains why the Thais may not have been fully informed. The army moved out in March B.E. 2307 (1764).

The army under Mang Maha Noratha set out on September 25, B.E. 2308 (1765), as this force traveled a shorter distance and targeted cities entirely within Siamese territory.

Both armies recruited more troops as they advanced; the longer the campaign lasted, the greater their manpower became. At the time of the siege of Ayutthaya, the total Burmese forces numbered approximately 80,000 troops (Sunetra Chutintharanon, 1998: 18).

The Burmese military organization.

(Image from the book “The Fall of Ayutthaya, Second Time, B.E. 2310”)

North | The Burmese Military Deployment | West |

Nemyow Sihabodi Kyawdin Thihathu Kuncheng Majaw 100 1,000 20,000 Suppress the Lanna rebellion, attack Lan Xang March toward Ayutthaya | Commander Deputy Commander Elephants Horses Soldiers Mission | Maha Nawrahta 100 elephants Attack Phetchaburi, Ratchaburi, |

All troops moved out from Ava. | Movement | They marched to join forces with another contingent, which was recruited from Hanthawaddy, Martaban, Tenasserim, Mergui, and Tavoy, totaling 30,000 soldiers. |

Departed from Ava in March 1764 (B.E. 2307). | Schedule | Departed from Tavoy on September 25, 1765 (B.E. 2308). |

5. The two armies began their movements six months apart due to different missions and distances, planning to converge at the target simultaneously.

Considerations:

Causes of the war

According to Burmese sources, King Mangrai (Mingyi) had long prepared for the conquest of Ayutthaya in advance.

The Thai side records no other apparent cause except that Burma perceived Siam as weak.

The causes from both sides are consistent: the Burmese intended to invade Siam, and Siam was seen as vulnerable; therefore, Burma launched the campaign against Siam.

2. Operations of the Burmese Army

The operations conducted by the Burmese army during this campaign were essentially a form of plundering, which was almost customary in warfare at that time. It was common for small units of soldiers to break ranks and commit atrocities or misconduct, although such actions were unlikely to have been officially sanctioned by the high command. However, in this instance, both Burmese armies conducted themselves in a manner that can be described as raids or plundering. The English term “raid” is even used to describe their operations. Therefore, it can be concluded that the conduct of the armies at that time indeed amounted to plundering, as confirmed by both Thai and foreign sources.

The Burmese army’s conduct was reportedly severe and likely ordered or at least condoned by King Mangrai (Mingyi). The king, known for his passion for warfare, chose not to personally lead the campaign, indicating the severity of the situation. This decision suggests it would be difficult to interpret otherwise.

The military advance progressed beyond initial expectations, moving directly toward Ayutthaya. Initially, the Burmese intended only to plunder the Thai frontier towns—conducting what is known as “hit-and-run raids,” typical small-scale operations involving rapid incursions into enemy territory to gather intelligence, cause disruption, or sabotage, before withdrawing. Each army acted independently and seized what they could. The relative weakness of the Siamese encouraged the Burmese to press further, eventually attacking Ayutthaya itself. This unsanctioned escalation is likely why King Mangrai did not personally lead the campaign as a royal honor.

According to Burmese chronicles, the reason King Mangrai did not command the campaign in person was due to a minor border conflict between Burma and China. The incident began when a Chinese merchant selling goods in Ban Mo, a town in the Tai Yai region, had his merchandise stolen by Burmese officials. Upon failing to retrieve his goods after complaining to the local authorities, the merchant appealed to officials in Yunnan province. Another Chinese merchant selling in Chiang Tung experienced a similar issue: Burmese officials purchased goods but refused to pay, leading to a dispute in which a Chinese man was killed. These grievances were reported to Yunnan authorities, who were then stirred up by Tai Yai exiles living there. Consequently, the Yunnan governor reported the matter to the Qing Emperor Qianlong, who ordered a military expedition to retaliate by attacking Chiang Tung.

In response, the Burmese court in Ava dispatched Ahsa Wun Gyi (Wun Hkyee Mahasi Hsura) with 20,000 troops to repel the Chinese army starting in October 1766 (B.E. 2309). This was actually the second Burmese force sent, as the first expedition had failed. This event coincided with the Burmese siege of Ayutthaya, when the Burmese forces were stalled and forced to endure the rainy season without withdrawing as they had in previous campaigns.

China launched military campaigns against Burma four times. On two occasions, the Chinese armies were forced to retreat. In the third campaign, a large Chinese force invaded Burmese territory in December 1767 (B.E. 2310), coinciding with significant events in Siam: in April 1767, Ayutthaya fell, and between October and November 1767, King Taksin defeated the Burmese at the Pho Sam Ton camp.

The third and fourth Chinese campaigns involved massive troop deployments. During the fourth campaign, Ahsa Wun Gyi (Wun Hkyee Mahasi Hsura) demonstrated great perseverance, managing to intercept and encircle the Chinese forces, compelling the Chinese commander to send emissaries to negotiate a ceasefire. Burma agreed to a peace treaty that allowed the Chinese troops and their weaponry to safely withdraw beyond Burmese borders, thus ending the war between China and Burma (Kachorn Sukphanich, 2002: 265-271).

For the Siamese, the first phase of warfare was characterized as bandit-style plundering of various frontier towns, reflecting the nature of Burmese military operations.

Some of the spoils taken by the Burmese remain in Burma to this day. The Burmese likely did not consider these items as trophies of shame but regarded them as rightful spoils of war.

3. Continuity of Burmese Aggression: From King Alaungpaya to King Mangrai

Historical chronicles, including the Royal Letter Edition, state that before ascending the throne, King Mangrai (Mang Kon) opposed his brother’s accession and was determined to become king himself. He was resolute in his ambition to conquer Ayutthaya. fAfter taking the throne, he pursued an imperial policy aimed at expanding his power and establishing an empire reminiscent of that of King Bayinnaung. It is recorded that “the Burmese ambition to conquer Ayutthaya was well known to the Siamese, who were deeply unsettled upon hearing news of his coronation.” Upon examination, the Burmese desire to attack Ayutthaya was not isolated to King Alaungpaya’s reign or only King Mangrai’s era. Instead, it was a continuous aspiration passed from father to son over two generations, creating a historical cycle of repeated conflict (Janya Prachitromron, 1993: 50-57). Professor Rong Sayamanont (1984: 40) further analyzed this persistent pattern.

The Ho Kaeo Chronicle provides a detailed and extensive account of King Mangrai’s military campaign against Ayutthaya, spanning as much as 40 pages in print. However, the summary by Sir Arthur Phayre states the following:

Mangrai inherited royal bloodline and military prowess from his father, Alaungpaya. Shortly after ascending the throne, he prepared to launch a campaign to attack Ayutthaya to avenge Alaungpaya, who had been despised by the Siamese. To this end, he reinforced the northern army by adding 20,000 troops under Nemyo Thihapate, the commander-in-chief of the northern forces. In the Royal Letter Edition of the chronicles, Nemyo Thihapate is referred to as Posuphla (Sang Phatthanaothai, n.d.: 130).

3.5 How was the military operation of Nemyo Thihapate, the commander-in-chief of the northern Burmese army?

Nemyo Thihapate reached Chiang Mai and thoroughly subdued the entire region. Chiang Mai submitted to his control. To prevent being attacked from behind, he then advanced to invade Lan Xang. The king of Lan Xang, who personally led his army, was decisively defeated and agreed to become a tributary state of Burma. After that, the Burmese commander took control over the Tai Yai (Shan) cities and ordered the army to prepare weapons. By mid-August of that year, Nemyo Thihapate commanded a force of 40,000 troops, mostly Tai Yai. He then marched southward toward the city of Tak as his first target.

Battle of Tak: The Lord of Tak, recognizing the enemy’s superior strength, chose to defend within the city. The Burmese troops fought valiantly and captured Tak in a short time. Afterwards, they advanced to Ra Haeng, which was easily seized because the local lord surrendered. Kamphaeng Phet was another city that the Burmese took with little resistance. The Burmese then moved to the Yom River basin to attack Sawankhalok. The Lord of Sawankhalok had prepared strong defenses, which forced the Burmese to use significant force before ultimately capturing the city. Subsequently, the army moved down to Sukhothai, where the local lord submitted peacefully. From there, they proceeded to Phitsanulok. Phitsanulok, fortified with strong bastions, did not surrender easily, and the Burmese had to use military force to capture the city.

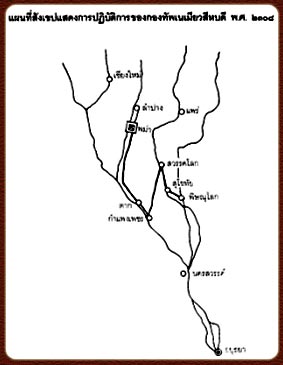

The organization and deployment of forces under Nemyo Thihapate

———————–

Army

Navy

———————–

Rear guard

Number of brigades

War elephants

Cavalry

Troops

Commander

10 regiments (9 from towns, 1 under direct Burmese control)

100

300

8,000

Sirirachatthajan

15 regiments (14 from towns, 1 under Burmese control)

200

700

12,000

Tadomengtheing

20

300 boats

Kuncheng Yamagyaw

13

Nemyow Thihapate

Nemyo Thihapate’s army consisted of a total of 58 divisions, supported by 300 elephants, 1,000 horses, and 43,000 soldiers. The army departed from Lampang in September 1765, with their first objectives being the cities of Tak and Phitsanulok. Upon capturing Phitsanulok, Nemyo Thihapate stayed there for 10 days to reinforce his forces by adding more elephants, horses, and soldiers. Afterward, he reorganized the army into two groups, each composed of 10 divisions, led by commanders Sirirachatatan and Jokongjodu. These two forces were assigned to advance southward toward Nakhon Sawan and Ang Thong, while Nemyo Thihapate established his headquarters in Phitsanulok. Local Thai rulers, recognizing the strength of the Burmese army, surrendered without resistance and willingly provided elephants, horses, and weapons. The commanders also sent the local rulers and their families to report to Nemyo Thihapate in Phitsanulok.

(Image from the book The Fall of Ayutthaya, Second Time, B.E. 2310)

Consideration:

From the northern direction, Nemyo Thihapate’s army advanced from Lampang to subdue the northern cities. Among the six northern cities, three resisted and three submitted. The cities that resisted were Tak, Sawankhalok, Kamphaeng Phet, and Phitsanulok, while the cities that submitted were Raheng, Kamphaeng Phet, and Sukhothai. In summary, the cities were evenly split between resistance and submission. Subsequently, Nemyo Thihapate organized two vanguard divisions to advance further southward, reaching Nakhon Sawan and Ang Thong.

Many Thai cities were already heavily conscripted to serve at the capital. The Thai forces from these provinces came out to resist but were overwhelmed and suffered a crushing defeat. Nemyo Thihapate continued his march along the river, gathering supplies and destroying some Thai villages along the way. However, these acts were mainly intended to intimidate the Thai, discouraging them from following the Burmese army. The Thai were unable to unite their forces to oppose the Burmese effectively because, after the end of the Alompanya Kyay war, Thailand had not prepared for another conflict. Even though the Burmese did not cease their invasions for five years, they advanced from the north and established positions east of Ayutthaya around January 20, 1766 (near Paknam Prasop, about 2 kilometers from Ayutthaya).

3.6 How did the Southern Burmese army under Maha Norahta operate?

The army led by Maha Norahta, the commander-in-chief of the southern army, consisted of 20,000 troops. They moved from Martaban (Mottama) to the city of Tavoy (Dawei) and stayed there until the end of the rainy season in B.E. 2308. Afterwards, they advanced towards Mergui (Myeik), crossed the Tenasserim mountain range, and attacked Kanchanaburi and Suphanburi. Then, they passed through the Thai coastal towns of Kui, Pranburi, Phetchaburi, and Ratchaburi before turning north toward Ayutthaya. The campaign took less time than during the reign of King Alaungpaya. However, along the way, the army paused to gather supplies. At Phetchaburi, the Thai army mobilized to resist but had insufficient forces.

The battle: The governor of Phetchaburi was aware that the Burmese army had arrived in large numbers, so he prepared to defend the city. When the Burmese forces reached the city, they divided their troops into two groups: one group used ladders to scale the walls, while the other dug at the foundations of the city walls. The Burmese were able to capture the city in a short period of time. Once inside, the soldiers looted the city; any soldier who seized or captured valuables such as gold or goods was allowed to keep them personally, while the military equipment was reserved for the commanders. This was the practice the Burmese applied to every city that did not willingly submit.

After securing the city, the Burmese required the local governor and officials to take an oath of allegiance and establish a permanent garrison. Then, the army moved on to Ratchaburi.

When the governor of Ratchaburi learned that Phetchaburi had fallen, he submitted to the Burmese without resistance. The Burmese likewise had the governor and officials swear allegiance, and then proceeded to attack Suphanburi. The governor of Suphanburi also submitted peacefully, allowing the Burmese to take the city with ease.

From Suphanburi, the Burmese army turned westward to attack Kanchanaburi, a city well-fortified with strong arms and abundant supplies. The governor of Kanchanaburi resisted and refused to submit. However, despite their determined defense, Kanchanaburi eventually fell to the numerically superior Burmese forces.

Afterwards, the Burmese advanced to Sai Yok and proceeded to capture two more cities named Swanpong and Saleng, though their exact locations in Thailand are unknown.

Having conquered these seven cities, the Burmese organized their forces from each into seven divisions. Mengji Kama-Nisanda was assigned to lead the vanguard, while Maha Norahta himself commanded the main royal army comprising 50 divisions, totaling 57 divisions marching towards Ayutthaya.

Fierce battles ensued between the Burmese and Thai armies, with the Thai forces suffering defeat. By January 1765 (B.E. 2308), Maha Norahta’s army had established a stronghold to the northeast of Ayutthaya (outside the island city, near Thung Phukhao Thong, less than 3 kilometers from Ayutthaya). The two Burmese armies coordinated their operations effectively.

NOTE:

Police Lieutenant Colonel Pisarn Senaves (1972: 311) explains that “Maha Norahta” is the title of a Burmese noble, not a personal name. The book Thai Fight Burmese by Somdet Krom Phraya Damrong Rajanubhab states that this Maha Norahta’s actual name was Mang Lasiri. The book also explains that “Nemyo Thihapate” is likewise a Burmese noble title — a commander who led the army to conquer Ayutthaya — but does not specify the real name of this individual. On this matter, Khajorn Sukphanich (2002: 263) states that Nemyo Thihapate’s original name was Aphayakaminee.

The book Interesting Facts about Thonburi published by the Foundation for the Conservation of Ancient Monuments in the Old Palace (2000: 147) mentions the position of Nemyo Thihapate, known as Posupala, a Burmese military title. This name appears in the Burmese chronicles describing the conquest of Ayutthaya in 1767 (Burmese year 1129), where he is referred to as Nemyo Thihapate. The name also reappears in chronicles in 1771 (Burmese year 1133), during a conflict between Chao Suriyawong, the ruler of Luang Prabang, and Chao Siribunso, the ruler of Vientiane. Chao Siribunso requested King Mangra to send troops for assistance. King Mangra appointed Chikchingbo as the vanguard and Posupala as the commander-in-chief to support Vientiane. Posupala led the army to attack Luang Prabang, where Chao Suriyawong, unable to resist, submitted to Burmese authority. Afterwards, King Mangra ordered Posupala to station the army at Chiang Mai to defend against the Siamese forces. Later, in 1773 (Burmese year 1135), Posupala led the army to attack Phichai after Chikchingbo had previously attempted but failed. On this occasion, Posupala was defeated by Chaophraya Surasi and Phraya Phichai, who then returned victorious.

2. Burmese Military Routes

Historically, when the Burmese armies marched to invade Siam, there were four main routes they commonly used to enter the country:

Via Chiang Mai

Via the Mae Lamao Pass, Tak Province

Via the Phra Chedi Sam Ong (Three Pagodas Pass), Kanchanaburi Province

Via the Singkhon Pass, Prachuap Khiri Khan Province

(Source: Police Major Pisal Senaves, 1972: 321)