King Taksin the Great

Chapter 2: Ayutthaya and the Conditions of Late Ayutthaya before the Fall of the Kingdom

2.1 What is the full name of Ayutthaya?

The full name of Ayutthaya is:

“Krung Thep Maha Nakhon Baworn Thawarawadi Sri Ayutthaya Mahadilok Phop Noppharat Ratchathani Burirom.”

This map was drawn by R.P. Placide, a geographer in the French embassy sent by King Louis XIV during the reign of King Narai in 1686 CE (2229 BE). It shows the French ship, led by Chevalier de Chaumont, entering via the Sunda Strait, passing Sumatra and Java, through Malay, into the Gulf of Siam, and up to the Chao Phraya River. (From the book “Ayutthaya”)

2.2 How long was Ayutthaya the capital city?

Ayutthaya served as the capital for 417 years — from 1350 to 1767 CE (1893–2310 BE).

2.3 What were the defining characteristics of Ayutthaya as a capital city?

There are recorded accounts concerning the city of Ayutthaya found in historical documents such as the Testimonies of the Inhabitants of the Old Capital and those attributed to Khun Luang Hawat (King Uthumphon). These narratives originated from the second fall of Ayutthaya, when the Burmese took many Siamese as prisoners of war. The Burmese authorities documented the testimonies of these captives in the Burmese language. Over a century later, a translated version was discovered—first rendered into Mon, and then retranslated into Thai. These documents contain significant historical insights about the former capital.

Ayutthaya was originally established at Nong Sano, located at the confluence of several rivers: the Chao Phraya, Lopburi, Pa Sak, and Noi Rivers. This strategic position provided convenient waterway connections to various cities within the kingdom. Initially, Ayutthaya was not an island. During the reign of King Maha Chakkraphat, a canal—known as Khlong or Khu was excavated, branching off from the Lopburi River near Hua Ro and connecting to the Bang Kacha River (or Chao Phraya River) in front of Pom Phet Fort. This transformation effectively surrounded Ayutthaya with water, turning it into an island and providing natural defense against enemy advances. A major river flowing southward from Ayutthaya opened into the Gulf of Thailand, enabling large foreign trading vessels to navigate directly to the city’s harbor near Pom Phet Fort. Consequently, Ayutthaya became an important international port city and a vital center for trade exchanges between European countries such as the Netherlands and France, Middle Eastern countries like Iran, South Asia including India, and East Asian nations such as China, Vietnam and Japan.

Map of Ayutthaya and its rivers

(Image from the book Ayutthaya)

The Kingdom of Ayutthaya (1351–1767 CE / 1893–2310 BE)

Map by François Valentijn, 1726 CE (2269 BE)

(Image from the book Ayutthaya)

Ayutthaya was originally protected by earthen walls, later replaced with brick walls during King Maha Chakkraphat’s reign. The walls stretched around 310 sen long and stood about 4 wa high, with forts placed at intervals. Notable forts included Phet Fort in the south near Bang Kachao and Maha Chai Fort near Hua Ro Market, which housed the famous “Prab Hongsa” cannon. These forts played key roles in defending Ayutthaya, especially during the Burmese siege before the city’s second fall.

Sad Kob Fort, also known as Toad’s End Fort, was situated at the corner of the city along the Hua Laem canal near Wat Phukhao Thong and housed the formidable Maha-Kan Mrittu-Rach cannon. Supharat Fort, Pak Tho Fort, and Tai Sanom Fort were located further north of Sad Kob Fort, near the Nai Kai or Naikan Fort. Hua Samut Fort and Pratu Khao Plueak Fort stood north of Wat Thammikarat. Mahachai Fort and Wat Khwang Fort were near the Front Palace, directly across from Wat Mae Nang Pluem. Hor Ratchakrut Fort was positioned in front of Wat Suwannararam. Champaphon Fort, an outer-city fort, lay beyond the Pratu Khao Plueak Gate, north of Wat Tha Sai, near the royal gardens of Wat Sopsawan. Phet Fort and Tai Khu Fort were located along the river near Bang Kacha. Wat Fang Fort lay between Wat Khok and Wat Tuek. Lastly, Ok Kai Fort was situated near Wat Khun Muang Jai.

In Ayutthaya, roads were typically elevated earthen embankments, either surfaced with bricks laid on their sides or left as bare earth. One such route was Patong Road, a royal procession route that passed in front of the city pillar shrine—nowadays known as Si Sanphet Road. Other important roads included Na Wang Road, which stretched from the Phra Kaeo Shrine to Patong, spanning 50 sen (approx. 2 km), and served as the route for receiving foreign envoys; Na Bang Tra Road (from Tha Sip Bia to Pa Maprao); Talat Chao Phraya Road (from the foot of Pa Than Bridge to Wat Chan); Lang Wang Road (beside the drum tower); and Na Phra Kal Road, where the intersection with Lang Wang Road formed a major city junction known as Talaeng Kaeng, near the area called Chi Kun. There was also Pa Maprao Road, located beside Wat Phlapphlachai. These descriptions align with the book Ayutthaya (2003: 317), which notes that most urban roads were compacted earthen paths, constructed using elephants and manual labor. They usually ran parallel to canals, and a few were paved with bricks. The grandest was Maha Ratthaya Road, paved with laterite and about 12 meters wide, which connected the ancient Royal Palace to the southern Chai Gate. This road was reserved for royal functions such as processions, royal kathin ceremonies, state funerals, and diplomatic receptions.

One of the most modern and bustling roads was Muhr Road, paved in a herringbone brick pattern using advanced construction technology, suitable for horse-drawn carriages and carts. It featured key districts such as the residence of Okya Wichayen, the royal envoy reception house, and areas for Brahmins, Muslims, and Chinese merchants. It also functioned as a major marketplace and transportation hub. Several other roads were named for their association with local markets or industries: Takua Pa Road, Pa Krieb Road (tray market), Ban Khan Ngern Road, Yan Pa Ya Road (spices and Thai goods), Pa Chomphu Road (fabrics), Pa Mai Road, Pa Lek Road, Pa Phuk Road (bedding), Pa Pha Khieo Road (clothing), Ban Chang Tham Ngoen Road, Chi Kun District (fireworks and liquor), Ban Kra Chi District (Buddha images), Khanom Chin District (sweets and incense offerings), Nai Kai District (Chinese goods), Pa Dinso District, Ban Hae District (fishing nets and rope hammocks), and Ban Phraam District (baskets and woven goods).

If roads were damaged, broken bricks would be removed or new layers added atop during flooding. Archaeological evidence shows that some roads were repaired up to three or four times. Today, certain roads within the city island follow ancient paths—for instance, U Thong Road, which was constructed atop the former city wall and parts of the original fortress spanning 12.4 kilometers. Rojana Road serves as a main external link to Ayutthaya Island. Numerous wooden or brick bridges—15 of each—were found, as recorded in late Ayutthaya documents. Examples include Pa Than Bridge, Chi Kun Bridge, Chinese Gate Bridge, Thep Mi Gate Bridge, Elephant Bridge, and Chain Bridge (Ayutthaya, 2003: 318).

The city was interlaced with numerous canals, each controlled by wooden sluice gates made from takian or teng rlang wood, featuring double-layered closures with earth fill in the middle to prevent flooding during the rainy season and conserve water for the dry months. Notable canals included Chakrai Yai (flowing from the palace to the river at Phutthaisong), Pratu Khao Pluak connecting to Pratu Chin (in Tha Sai district, leading to the southern river), Horattanachai Canal, Nai Kai Canal (below Chan Kasem Palace toward the river near Pom Phet), Pratu Chin Canal (south above Nai Kai), and Pratu Thep Mee or Khao Samee Canal near Pratu Chin. Additionally, Chakrai Noi lay above Pratu Thep Mee. The Pratu Tha Phra Canal fed the large urban reservoir called Bueng Chee Khan (Bueng Phra Ram), a crucial water source for the dry season when river levels dropped.

There were multiple sluice gates constructed to regulate the city’s water system, including Pratu Khao Pluak, Pratu Hor Rattanachai, Pratu Sam Ma, Pratu Chin, Pratu Thep Mee, Pratu Chakrai Noi, Pratu Chakrai Yai, and Pratu Mu Thaluang. Additionally, the city featured land gates, approximately six sok wide, topped with red clay prasat-shaped spires, as evidenced by the mural at Wat Yom’s ordination hall and descriptions in ancient texts.

Examples of these city gates include Pratu Si Chaiyasak, Pratu Chakkra Mahima, Pratu Maha Paichayon, Pratu Mongkhon Sunthon, Pratu Samana Phisan, Pratu Thawan Chetsada, Pratu Kanlayapirom, Pratu Udom Khongkha, Pratu Maha Phokharat, Pratu Chatnawa, Pratu Thakkinapirom, Pratu Phrom Sukhoth, Pratu Thawan Wijit, Pratu Olanrik Chatra, Pratu Thawan Nukun, Pratu Niwet Wimon, Pratu Thawan Uthok, Pratu Phra Phikhanesuan, Pratu Si Sapphathawan, Pratu Nakhon Chai, Pratu Phon Thawan, Pratu Sadeng Ram, Pratu Sadoak Khro, Pratu Tha Phra, Pratu Chao Prap, Pratu Chai, Pratu Chao Chan, and Pratu Chong Kut, among others. Today, all of these gates have been completely destroyed, leaving behind only their names in historical records and local memory.

The painting Afbeldine der Stadt Judiad illustrates the geographic and structural form of Ayutthaya as an “island city” surrounded by rivers. It presents a clear layout of the city, with roads and canals intricately interwoven, reflecting the transportation and urban planning of the period. (Image from the book Ayutthaya)

Royal Barges of the Ayutthaya Kingdom

From a Western illustration

(Image from the book “Ayutthaya”)

A royal barge dockyard was located in the Khu Mai Rong area, between Wat Choeng Tha and Wat Phanom Yong, housing over 150 vessels. The royal boathouse stretched about 245 meters from Wat Teen Tha to Khu Mai Rong. (Locals still occasionally find boat fragments today.) Among the fleet were two large sea-going royal barges—Phra Krut Phaha and Phra Hong Phaha—used for fishing marlins and sharks. Other grand barges included Kaeo Chakramani, Suwan Chakkarat, and secondary ones like Suwan Phiman Chai, Sammut Phiman Chai, and Salika Long Lom. Roughly 500 oarsmen operated the fleet, many from Ban Pho Riang and Ban Phut Lao.

Mahachakrakrot Cannon Cast in bronze, featuring a pair of lifting handles. The rear of the barrel is adorned with floral and leaf patterns, a crown motif atop traditional Thai kanok designs, and a decorated touch hole. It was manufactured at the Douai arsenal in France by J. Bérenger on September 12, 1768 (B.E. 2311). Today, it is displayed in front of the Ministry of Defence.

(Image from http://www1.mod.go.th/opsd/sdweb/cannon3.htm)

Ayutthaya possessed many renowned cannons with imposing and symbolic names that reflected both military might and spiritual beliefs. Among these were Narai Sanghan, which was already in use by 1553 (B.E. 2096), prior to the First Fall of Ayutthaya; followed by Maha Ruek, Maha Chai, Maha Chak, and Maha Kal. Later, during the Second Fall of the capital in 1767 (B.E. 2310), other cannons such as Prap Hongsa, Chawa Taek, Angwa Laek, Lawaek Pinas, Phikhat Sanghan, Man Pralai, Mahakan, and Maha Mrityuraj were recorded. These names conveyed a mix of divine, mythological, and fearsome qualities, such as the ominously named Tapakhao Kwat Wat, meaning “the white-robed ascetic sweeps the temple.” Each name reflected not just weaponry but also cultural narratives and the deep intertwining of warfare and ritual in the Ayutthaya kingdom.

A diagram showing the locations of the royal halls within the Grand Palace, which were first established during the reign of King Boromtrailokkanat.

As Ayutthaya grew into a kingdom, it needed to reorganize its system to suit its evolving circumstances.

(Image from the book Sanphet Prasat Throne Hall)

ChatGPT said:

In the royal palace of Ayutthaya, there were several throne halls where the kings resided, built during the reign of King U Thong (B.E. 1893–1912). These included Phra Thinang Phai Thun Maha Prasat, Phra Thinang Phichaiyat Maha Prasat, and Phra Thinang Aisawan Maha Prasat, which are believed to have been constructed of wood. Later, after a fire, King Boromtrailokkanat granted the original palace grounds to be converted into a Buddhist monastery area in B.E. 1991. Today, this area corresponds to Wat Phra Si Sanphet, where three large stupas stand beside the Viharn Phra Mongkhon Bophit, housing the royal ashes of King Boromtrailokkanat, King Borommaracha III, and King Ramathibodi II.

Phra Thinang Sanphet Prasat (Replica) at Muang Boran, Samut Prakan Province

(Image courtesy of Muang Boran)

Phra Thinang Sanphet Prasat was the most important and oldest royal throne hall, serving as the venue for royal administration and major state ceremonies of the kingdom. It was completely destroyed by fire set by the Burmese during the second fall of Ayutthaya in 1767 (B.E. 2310), leaving only its foundation ruins behind.

(Image from the book Phra Thinang Sanphet Prasat)

The ruins of the foundation of Phra Thinang Sanphet Prasat in Ayutthaya show narrow stairways built to accommodate the traditional practice of crawling up to the throne hall, in accordance with ancient royal customs.

(Image from the book Phra Thinang Sanphet Prasat)

Phra Thinang Sanphet Maha Prasat (replica) features a long front and rear pavilion with shorter side pavilions. The curved roof runs parallel to the base, and the roof’s finials are modeled after the intricately carved wooden decorations seen in the Vihara of Phra Buddha Chinnarat, Phitsanulok. (Image courtesy of Muang Boran)

Inside the throne hall, both the front and back sides each have three doors. The side doors are smaller, while the central door is larger, featuring a pointed mandapa-style spire. The base is designed as a stepped platform adorned with intricate motifs of Thepphanom (celestial beings), Garuda, and Singha (mythical lions).

The original Sanphet Maha Prasat throne hall—the central hall—featured mural paintings depicting the ten incarnations of Narayana, as documented in the Ayutthaya-era royal archive, the Hor Wang book. It once housed the three-tiered golden royal throne decorated with precious gems, which the Burmese took to Ava when they sacked Ayutthaya in 1767 (B.E. 2310). This throne hall was historically significant as the site of royal coronations and the reception of important foreign envoys during King Narai’s reign, such as the French ambassadors Chevalier de Chaumont and La Loubère. Later, King Rama I ordered a replica to be built as the Inthraphisek throne hall, but it was destroyed by fire, leading to the construction of Dusit Maha Prasat instead.

(Image courtesy of Muang Boran)

The upper walls surrounding the throne hall are decorated with intricate patterns of rice sheaves and lotus buds, gilded and adorned with white glass mosaics. The lower sections feature guardian motifs framed in rectangles, also gilded and embellished with white glass. The windows are inlaid with mother-of-pearl designs, inspired by the door panels of the main hall at Wat Phra Sri Rattana Satsadaram.

(Image courtesy of Muang Boran)

The star-patterned ceiling is gilded and decorated with glass, modeled after the ceiling of the prang at Wat Phra Sri Rattana Mahathat in Chiang Mai.

(Image courtesy of Muang Boran)

During the reign of King Boromtrailokkanat (B.E. 1991–2031), a new palace was constructed north of the old one, including the grand halls Sanphet Maha Prasat and Benjarat Maha Prasat. Later, in the reign of King Prasat Thong, the Sri Yot Sothon Maha Phiman Banyong was built, later renamed Chakrawat Paichayon Maha Prasat. Other halls such as Suriyan Amarin, Yannong Rattanat, and Phiman Ratchaya were also constructed. Today, some of these halls have been reconstructed at Ancient City (Muang Boran) in Bang Pu, as the originals were mostly destroyed, leaving only foundations or nothing at all. A three-tiered drum tower, 10 wah high, was built at Talangkaeng. The top level, called Maha Rueksa, served as a lookout for enemies; the middle level, Maha Rangab, was for watching fires. If a fire broke out outside the city, the drum was struck three times; if within or near the city walls, the drum beat continued until the fire was extinguished. The lowest level held a large drum called Phra Thiwaratri, used to mark times like noon, meetings, dawn, dusk, and evening. The drum tower was guarded by the Krom Phra Nakhonban, who kept cats to prevent mice from damaging the drums. Every morning and evening, market shops near the prison paid five bía coins each to buy grilled fish for the cats.

Back in King Narai’s era, when La Loubère came as an envoy, he estimated Ayutthaya’s population at about 150,000 people. Most lived in wooden houses along canals, rivers, and near the city walls. The city center was mostly open space with few houses. Stone or brick buildings were rare—mostly foreign merchants’ shops near Thaiku pier, the Korasan (or Kochasan) building of Persians in Lopburi, and settlements of Portuguese, Dutch, and Japanese along the river at Pak Nam Mae Bia, just south of Pom Phet. The French built churches and homes near the Takhian canal in the north.

There were many Buddhist temples, such as Wat Phanan Choeng, located at the tip of Bang Kacha near the sea port at the mouth of the Mae Bia River. According to the Royal Chronicle of Ayutthaya by Luang Prasert Aksornniti, it was recorded that “In Chulasakarat 696, the year of the Rat, the principal Buddha image of Phanan Choeng was first established,” meaning the statue was created in B.E. 1967, 26 years before Ayutthaya was established as the capital. Wat Mae Nang Pluem is an ancient temple from the Ayodhya period, located near Wat Na Phra Meru, where the Burmese set up cannons to attack Ayutthaya before its second fall. Wat Khok Phaya, or Khok Phraya, behind Wat Na Phra Meru outside the city island near Khao Thong, was a place where high-ranking nobles were executed by “ton chan” (a form of punishment). Wat Sala Pun is notable for its late Ayutthaya period murals.

There were large stern-swinging boats from Phitsanulok carrying sugarcane juice and tobacco to sell in front of Wat Kluay. Similarly, big stern-swinging boats from Sukhothai brought northern goods and docked along the riverbanks and canals near Wat Mahathat. The Mon people transported young coconuts, mangrove wood, and salt to sell at the mouth of Kokaew Canal. Carts from Nakhon Ratchasima carried lacquer, beeswax, bird wings, Tarang cloth, Sai Bua fabric, leather, tendon, and sheet meat to sell at Sala Kwan.

Villagers from Wiset Chai Chan district traveled by boat carrying unhusked rice to sell at Ban Wat Samo, Wat Khanoon, and Wat Khanan. Locals there operated rice mills and rice polishing machines, as well as sailboats and distilleries. The Chinese brewed and sold liquor at Ban Pak Khao San. Boats called Ra Raeng from Tak district and Hawng Yiao boats from Phetchabun carried camphor, incense, iron shrimp hooks, rattan, bamboo, rubber oil, tobacco, and various goods to dock and sell at different local districts. Outside the city walls near Phutthaisawan, locals pressed sesame oil to sell. Outside Chakkrai Gate, bamboo rafts and pillar poles were sold. People from Yi San village, Laem village, and Bang Thalu in Phetchaburi carried shrimp paste, fish sauce, salted crabs, snapper, mullet, mackerel, and grilled stingrays to sell. At Ban Pun near Wat Khian, they made and sold lime. At Ban Phra Kran, fishermen sold snakehead fish to city residents for Songkran festival offerings. At Ban Na Wat Ratchaplee and Wat Tharma, coffins and funeral supplies were sold. The Patong area sold cotton. Talang Kaeng market, known as the “market in front of the prison,” sold fresh goods daily. This place was also an execution ground where prisoners were beheaded, dismembered, and their body parts displayed along Pat Tone Road near the Drum Tower and Wat Phra Ram. Another execution site was at Tha Chang Gate by the Lopburi River, north of the city island near Wat Khongkharam. Both sites were open for public viewing during executions.

During the monsoon season, Chinese junks and merchant ships from Surat (India), England, France, and the Dutch East Indies would anchor their vessels at Ban Tai Khu and transport goods into warehouses within the city walls. Ships from Javanese and Malay traders also brought areca nuts to sell at Khlong Khu Cham. (In later periods, several sunken junks were discovered beneath the water, some showing signs of having been burned. Divers had even recovered ancient artifacts for sale.) The Chinese distilled liquor and raised pigs in the Khlong Suan Phlu area, and set up distilleries by the Hua Laem River, south of Wat Phu Khao Thong, near the shrine of Nang Hin Loi. Cham (Champa) traders made and sold various sizes of lantai mats at Ban Tai Khu, wove silk and cotton textiles at Wat Lot Chong, and produced coir ropes from coconut husks to sell to English Surat shipmasters at Ban Tha Kai Yi.

(Source: Fine Arts Department, Collected Stories of the Old Capital by Phraya Boran Rachathanin, published for the cremation of Miss Phen Dechakup on December 12, 1998, and Testimonies of the Inhabitants of the Old Capital by Prince Damrong Rajanubhab, Khlang Witthaya Publishing, 1972; cited in Athorn Chantawimol, “King Borommakot (1732–1758),” in History of the Thai Land: From the Dinosaur Age to Ayutthaya and the 1992 Black May Incident, 2003: pp. 223–227.)

2.4 How many kings ruled the Ayutthaya Kingdom? Which royal dynasties did they belong to? And what was the final royal dynasty of Ayutthaya?

There were five royal dynasties during the Ayutthaya period when it served as the capital of the kingdom:

The Chiang Rai Dynasty

The Suphannaphum Dynasty

The Sukhothai Dynasty

The Prasat Thong Dynasty

The Ban Phlu Luang Dynasty

The last royal dynasty was the Ban Phlu Luang Dynasty. Altogether, the Ayutthaya Kingdom had 33 monarchs (or 34, if Khun Worawongsathirat is included). They were as follows:

- 1. The Chiang Rai Dynasty (also known as the Wiang Chai Phrakan Dynasty)

King U Thong

(Image from the Illustrated Book of Rattanakosin Sculpture)

King Ramathibodi I (also known as King U Thong) reigned from 1350 to 1370 (20 years).

King Ramesuan, son of King Ramathibodi I, reigned twice:

- In 1370 (for 1 year), he abdicated the throne in favor of Khun Luang Pha Ngua and relocated to rule in Lopburi.

- Again from 1388 to 1395 (7 years).

- 2. Suphanburi Dynasty (also known as the Wiang Chai Narai Dynasty)

3) King Borommaracha I (Khun Luang Phon, from the Wiang Chai Prakan dynasty, was the uncle of King Ramesuan. He came from Suphanburi, seemingly to claim the throne, but King Ramesuan willingly gave up the throne to him.) Reigned 1370–1388 (B.E. 1913–1931).

4) King Thong Lan (or King Thong Chan), son of Khun Luang Phon, reigned for only 7 days before King Ramesuan returned from Lopburi, entered the palace, and executed King Thong Lan.

5) King Ramrachathirat (son of King Ramesuan) reigned 1395–1409 (B.E. 1938–1952) for 14 years. The chief minister, Chaopho Luang Maha Senabodi, rebelled, seized Ayutthaya, and handed the throne to King Intharacha (from the Wiang Chai Narai dynasty).

6) King Intharacha, also called King Indraracha or King Phra Nakhon Intharachathirat (grandson of King Borommaracha I), reigned 1409–1424 (B.E. 1952–1967) for 14 years. He had three sons — Chao Ai Phraya, Chao Yi Phraya, and Chao Sam Phraya — who were appointed rulers of Suphanburi, Praek Sriracha, and Chainat, respectively.

When King Intharacha passed away, Chao Ai Phraya and Chao Yi Phraya each raised their armies to fight for the throne. Their battle was so fierce that both brothers ended up fighting on elephants and were simultaneously decapitated. The chief minister then invited Chao Sam Phraya to ascend the throne as King Borommaracha II (Chao Sam Phraya, son of King Intharacha), who reigned from 1424 to 1468 (B.E. 1967–1991) for 24 years.

The elephant duel between Chao Ai and Chao Yi for the throne (Image from the book Ayutthaya)

King Boromtrailokanat

8) King Boromtrilokkanat (son of King Borommaracha II) reigned from 1648 to 1592 BE (1991–2031), for 39 years.

9) King Borommaracha III reigned from 1592 to 1595 BE (2031–2034), for 4 years.

10) King Ramathibodi II (younger brother and son of King Boromtrilokkanat) reigned from 1595 to 1633 BE (2034–2072), for 38 years.

11) King Borommaracha IV (also known as King Maha Buddhangkura or No Buddhangkura) reigned from 1633 to 1637 BE (2072–2076), for 5 years.

12) Prince Ratsadathirat reigned in 1637 BE (2076) for 5 months. His uncle marched an army from Phitsanulok, captured and executed him, then took the throne as King Chairachathirat.

13) King Chairachathirat (son of King Ramathibodi II) reigned from 2077 to 2089 BE (1634–1646), for 12 years.

14) King Kaew Fa, or King Yodfa (son of King Chai Rajathirat and Queen Sri Sudachan), reigned from 1646–1648 BE (2 years). During his reign, Queen Sri Sudachan acted as regent and later elevated Khun Worawongsa (or Khun Chinarat) to kingship, though his reign was brief and not officially recognized by historians. Khun Phiren Thep (from the Wiang Chai Buri dynasty) and nobles conspired to arrest and kill Khun Worawongsa and Queen Sri Sudachan, then offered the throne to King Thein Racha, a royal relative of King Chai Rajathirat.

15) King Maha Chakkraphat, also known as King White Elephant (King Thein Racha, younger maternal half-brother of King Chai Rajathirat), reigned 1648–1663 BE (15 years).

16) King Mahinthrathirat (son of King Maha Chakkraphat) reigned 1663–1669 BE, ruling jointly with his father. During his reign, the Burmese under King Bayinnaung invaded Siam. Internal divisions and treason weakened the kingdom, eventually causing Siam to lose independence to Bayinnaung. King Mahinthrathirat was captured and taken to Hanthawaddy but died en route.

The Sukhothai Dynasty (also known as the Wiang Chai Buri Dynasty)

17) King Maha Thammaracha Thirat (also known as King Sanphet I) reigned from 1569 to 1590 (22 years). During this time, Ayutthaya was a vassal state under Burma.

18) King Naresuan the Great, or King Sanphet II (son of King Maha Thammaracha Thirat), reigned from 1590 to 1605 (15 years). During his reign, King Naresuan declared independence from Burma in 1592.

19) King Ekathotsarot or King Sanphet III (younger brother of King Naresuan the Great) reigned from 1605 to 1620 (15 years).

20) Crown Prince Si Saowaphak or King Sanphet IV (son of King Ekathotsarot) reigned in 1620 (less than 1 year). He was overthrown and executed by Phra Sri Sin, a royal rebel who then took the throne.

21) King Songtham or King Borommaracha I (maternal uncle of Crown Prince Si Saowaphak) reigned from 1620 to 1628 (8 years).

The Monument of King Naresuan the Great

22) King Chetthathirat or King Borommaracha II (son of King Songtham) reigned 1628–1630 (2 years). Chaophraya Klaihom seized power, executed King Borommaracha II, and gave the throne to King Athittayawong, the younger brother of Borommaracha II.

23) King Athittayawong, aged 9, ascended the throne in 1630 but ruled only about 7 months (some sources say 36 days). The council then decided to give the throne to Chaophraya Klaihom Suriyawong.

4. The Prasat Thong Dynasty

King Narai the Great

(from the Rattanakosin Kingdom Sculpture Manuscript)

24) King Prasat Thong, or King Sanphet V (formerly Chaophraya Klaihom Suriyawong), reigned from 1629 to 1655 (26 years).

25) Prince Chai (or King Sanphet VI) reigned 1655–1656 (1 year). He was a son of King Prasat Thong. Narai’s crown prince and Sri Suthammaracha led a rebellion, captured Prince Chai, and executed him.

26) King Sri Suthammaracha, or King Sanphet VII, reigned in 1656 for 3 months. Narai’s crown prince rebelled, causing a civil war, captured and executed Sri Suthammaracha, then took the throne.

27) King Narai the Great, or King Ramathibodi III (son of King Prasat Thong), reigned 1656–1688 (32 years). He suppressed rebellions led by Ok Phra Phet and Ok Luang Sor Sak, executing royal nobles. After King Narai died, Ok Phra Phet (Phetracha) ascended the throne.

- 5. The Ban Phlu Luang Dynasty

28) King Phetracha, or Somdet Phra Maha Burut (from Ban Phlu Luang, Suphanburi) reigned from 1688 to 1701 (15 years).

29) Somdet Phra Srisanphet VIII (commonly called King Suea) — formerly Khun Luang Sorasak, son of King Phetracha — reigned 1701–1707 (7 years).

30) King Tai Sa, or Somdet Phra Sanphet IX, also known as King Phumintharacha (son of King Suea), reigned 1707–1732 (23 years).

31) King Boromkosa, or Somdet Phra Boromrachathirat III (Prince Phon, younger brother of King Tai Sa), reigned 1732–1758 (26 years).

32) King Uthumphon, or Somdet Phra Boromrachathirat IV (Prince Dok Maduea, Krom Khun Phonphinit, son of King Boromkosa, commonly called Khun Luang Ha Wat), reigned briefly in 1758 for about 2-3 months before abdicating in favor of his elder brother.

33) King Ekatat, also known as Somdet Phra Thinang Suriyamarin or Somdet Phra Boromrachathirat III (Krom Khun Anurak Montri, commonly called Khun Luang Kheeruean, the elder brother of Prince Dok Maduea), reigned from 1758 to 1767. His reign saw the country severely decline, culminating in the Burmese conquest of Ayutthaya in 1767.

(From the Royal Chronicles of Ayutthaya, Luang Saraprasert Edition and Krom Phra Borommanuchit Edition, Volume 1, 1961: Table of Contents; and Political History of the Thai People – Three Revolutions by Prakob Choprakan, Somboon Khon Chalad, and Prayut Sithiphan, n.d.: pp. 45–47; also Historical Announcements, Year 18, Issue 1, 1984: pp. 43–45; and Thuan Boonyaniyom, 1970: pp. 163–167.)

2.5 What are the royal biographies of the last three kings from the Ban Phlu Luang dynasty?

- King Boromkhoja (r. 2275–2301 BE) was the 31st monarch of Ayutthaya. In 2275 BE, following the death of King Thai Sa, a fierce struggle for the throne broke out. The crown princes, Phra Aphai and Phra Poramet, clashed with the Great Uparaja (Phra Phon, or Prince Bandunnoi, younger brother of King Thai Sa and son of King Suea). The battle was bloody, ending with the Great Uparaja victorious. He executed both princes and ascended the throne as King Boromkhoja (also called Boromkosot). During his reign, he purged most of the palace officials loyal to Phra Aphai and Phra Poramet, weakening Ayutthaya’s military. However, he promoted trade, literature, and culture, overseeing works like Inao, Kap Hao Ruea, Punnovat Kamchan, Klob Thor Sirivibulkiti, and the Khlong Chalo Phra Phutthasaiyas.

King Boromkot (Phra Chao Yu Hua Boromkot)

In 2276 BE, nine Chinese junks arrived in Siam, and Siam also sent an envoy to China. In November 2279 BE, the Siamese armed forces laid siege to the Dutch settlement in Ayutthaya, due to a dispute over the pricing of Indian textiles brought by the Dutch.

In 2290 BE, King Boromkot traveled to worship at Phra Phutthabat in Saraburi by waterway, sailing along the Pasak River to Ban Tha Ruea, then continued by land to Wat Phra Phutthabat. During this journey, Jacobus van der Heuvel, a Dutch merchant, accompanied the king and recorded visiting Pratuan Cave and Than Thong Daeng, and also watched a traditional play. At this time, the Muslim Bunnag family branch converted to Buddhism. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) purchased deer skins, stingray leather, and ironwood from Siam to sell in Nagasaki, Japan, while exporting tin, lead, and ivory to Batavia.

2292 BE, smallpox epidemic broke out, causing many deaths.

An illustration showing various sizes of stingray leather products from Siam that the Dutch took to Japan to make samurai sword handles in 1747 (2290 BE), during the reign of King Boromkot.

(Image from History of the Land of Thailand: From the Dinosaur Era Millions of Years Ago, the Ban Chiang Stone Age, Ayutthaya, the Black May Incident up to 2003)

NOTE:

Smallpox, also known as variola, is caused by the variolar virus. The last recorded case was in 1961 (B.E. 2504). It spreads through airborne droplets from secretions of infected people, such as nasal mucus, saliva, or by contact with skin lesions. The virus is resilient to various weather conditions, whether hot or cold, and easily transmits from person to person. Patients experience high fever, body aches, headaches, back pain, and abdominal pain. Some may show neurological symptoms like delirium, agitation, or lethargy. Following these symptoms, sores develop in the mouth, throat, face, torso, arms, and legs. The visible skin lesions start as clear pustules which soon turn cloudy and filled with pus.

Condition of children with smallpox

Similar to chickenpox but more severe, within 24-48 hours the pustules begin to form and it takes about 8-9 days for these pustules to start drying into black scabs, eventually turning into scars over 3-4 weeks. The contagious period starts from when symptoms first appear and continues through the first week, which is when the disease is most easily spread, until the scabs have fully dried. Currently, there is concern that this pathogen could be used as a biological weapon due to its effects on the respiratory system, along with other diseases such as Anthrax and the Plague. (Source: http://www.manager.co.th/Home/ViewNews.aspx?NewsID=4632818276285, July 14, 2004)

In 1751 (B.E. 2294), the Burmese lost the city of Ava to the Mon people.

On July 17, 1751 (B.E. 2294), the Sri Lankan royal envoy arrived at Ayutthaya and described,

“…Inside the city walls, there are many canals running parallel, with countless boats and people traveling by water, too many to describe… Shops sell various goods, including golden Buddha statues.” The Sri Lankan envoy who came to Siam recorded,

“On Wednesday, the 9th day of the waxing moon in the 7th month, the lead ship sailed into the river mouth and anchored at Amsterdam village, which the Dutch (Holland or present-day Netherlands) had built at the river mouth.” In the second Siamese envoy sent to Sri Lanka in 1752 (B.E. 2295), it was recorded,

“On Monday, the 15th day of the waxing moon in the 2nd month, departed from Thonburi city heading to the Dutch building at Bang Plakod.”

Map of the Chao Phraya River during the reign of King Tai Sa by François Valentijn (Amsterdam, 1726 / B.E. 2269)

(Image from the book Ayutthaya)

In 1753 (B.E. 2296), the Dutch East India Company sent 19 Thai monks to be ordained in Sri Lanka. The King of Kandy, Kirti Sri Rajasinha, had sent a royal envoy requesting Siamese monks to help revive the declining Buddhist faith there. In response, King Borommakot sent Phra Upali, Phra Ariyamani, and 50 other monks to Sri Lanka, bringing along a Buddha statue, the revered Buddha image called Phra Phuttha Patimakorn Ham Samut, and the Tipitaka scriptures. (This edition of the Tipitaka has been well preserved in Sri Lanka to this day.) The Siamese monks stayed at Buppharam Temple in Kandy and conducted the ordination to continue the Siamese Buddhist tradition.

Map of Lanka or present-day Sri Lanka

(Image from http://www-user.tu-chemnitz.de/. ../srilan-map.jpg)

Wat Kudi Dao (Image from http://www.pantip.com/cafe/gallery/topic/G2875425/G2875425.html)

This image is believed to be of Prince Uthumphon, who was captured by the Burmese after the war in 1767 (B.E. 2310).

(Image from the book Ayutthaya)

At the same time that year, King Alaungpaya, formerly a Burmese hunter named Mangongjaiya, conquered Ava and Hanthawaddy and ascended the throne as the Burmese king near the end of King Boromkhot’s reign.

King Boromkhot had a son, Prince Uthumphon, titled Krom Muen Phonphinit or Khun Luang Ha Wat, who served as the Great Uparaja (Deputy King), and Prince Ekathat (it is said that Prince Ekathat was blind in one eye).

During this reign, Wat Kudi Dao, an ancient temple built before the founding of Ayutthaya, was restored. (Athorn Chanthawimol, 2003: 220-222)

Note:

Wat Kudi Dao is an abandoned temple located along a road in the alley near Wat Kudi Dao, close to Wat Mahathong further east. There is no clear documented evidence about its construction history. The only record is in the Ayutthaya Royal Chronicles, which states it underwent major restoration during the reign of King Boromkotsarath (before he ascended the throne), when he held the title of Maha Uparat, in the year 1711 BE (2254 BE).

After excavation and restoration, it was found that the ancient site within Wat Kudi Dao was originally constructed during early Ayutthaya period. Evidence shows layers built over the main stupa and the ubosot (ordination hall) constructed atop the foundations of the original early Ayutthaya structures. This likely corresponds to a major restoration by King Boromkotsarath, alongside the construction of additional viharns (assembly halls) and smaller stupas within the temple grounds. To the north, outside the temple’s wall, there is a two-story building commonly called the “Kammalian Palace,” resembling the style of the Mahayong and Wat Chao Ya Palaces. It is believed this served as King Boromkotsarath’s residence during the restoration works at Wat Kudi Dao.

(Source: http://www.thai-worldheritage.com/thai/ayuth-monu-out-E.html, 15/7/2004)

- 2. King Uthumphon was the 32nd monarch of Ayutthaya. He was a royal.

Prince Uthumphon was the son of King Boromkot and Queen Phanwasanoi (Krom Luang Phiphitmontri, later promoted to Krom Phra Thepamat). When King Boromkot punished the Viceroy (Prince Thammathibet) for having an affair with the king’s consort, Princess Sangwan, both died. Krom Muen Thepphiphit, the minister, then petitioned King Boromkot to appoint Prince Uthumphon (also called Prince Dok Madeua) — who was then Krom Khun Phonphinit — as the new Viceroy in place of Prince Thammathibet.

Foreign records state that Prince Uthumphon was a clever and intelligent person who learned letters at the monastery from a young age. He was deeply devoted to Buddhism and had a modest character. Prince Uthumphon, Krom Khun Phonphinit, saw that the royal family was divided and feared future troubles. Therefore, he petitioned the king, claiming that Krom Khun Anurakmontri, his elder brother, was still alive, and requested that Prince Ektat, Krom Khun Anurakmontri, be appointed as the Viceroy. The king was very angry because this was not his wish. He declared that Krom Khun Anurakmontri was foolish, lacking wisdom and diligence, and if allowed to rule, would bring disaster to the kingdom. Not caring for personal matters above all, the king ordered Krom Khun Anurakmontri to become a monk so as not to obstruct state affairs. Fearing the king’s punishment, Krom Khun Anurakmontri complied and ordained. Prince Uthumphon, Krom Khun Phonphinit, did not dare to oppose the king further. In the year 2301 BE (1758 CE), King Boromkot then bestowed the Viceroy title on Krom Khun Phonphinit. In that same year, King Boromkot fell seriously ill and passed away. Prince Uthumphon, Krom Khun Phonphinit, the Viceroy, then ascended the throne.

Prince Ektat, Krom Khun Anurakmontri, who was the elder brother, later disrobed from monkhood. While King Boromkot was still ill, Prince Ektat declared himself independent and forcibly took residence in the Suriyamarn Throne Hall (or Phra Thinang Suriyamornrin), acting as if he were the king. King Uthumphon saw that his elder brother intended to seize the throne. Having no ambition for power himself, after ruling for just over three months, he willingly abdicated in favor of Prince Ektat. Then he entered monkhood again at Wat Assanawiha (or Assanawas Vihara), a royal monastery formerly called Wat Pradu Rong Tham, located outside the eastern moat of the royal city. After ordaining, the people respectfully called him “Khun Luang Ha Wat.”

(Tuan Boonyaniyom, 1970: 27–28)

NOTE:

After King Uthumphon (Krom Khun Phonphinit, also known as Khun Luang Ha Wat) abdicated the throne to King Ektat, he intermittently entered monkhood. At times, he resided at the Kham Yat Palace, which he built within the area of Wat Pho Thong, Kham Yat Subdistrict, Pho Thong District, Ang Thong Province. Because King Ektat showed disdain toward him, King Uthumphon separated himself and lived far from the capital. When the Burmese army approached the capital, King Uthumphon left monkhood to help lead the defense. After the conflict, he returned to monkhood and stayed for a while before finally residing at Wat Pradu Songtham, outside the city walls.

The Kham Yat Palace (replica) at Muang Boran, Samut Prakan Province

(Image courtesy of Muang Boran)

Kham Yat Palace, Ang Thong Province

(Image from Encyclopedia of Central Thai Culture, Vol. 3)

The Kham Yat Palace is believed to have originally been located within the grounds of Wat Pho Thong, which was still in use at the time. Later, it likely became abandoned during the fall of the capital. The palace is built of brick and mortar, elevated with a rectangular shape measuring about 10 meters wide and 20 meters long. The space beneath the building features an open area with small chambers or niches. The windows inside the palace are pointed arches, and the interior is spacious with wooden plank flooring. The base of the palace curves gently like the hull of a boat and consists of five rooms, with front and back porches, including a royal chamber. The roof structure has mostly collapsed. It is believed to date back to the 17th century, reflecting the architectural style popular since the reign of King Narai the Great. The palace has a rounded front porch on the east side. The roof no longer remains, leaving only the walls standing in this compact building.(Source: “Touring Ancient Cities: For Students,” 2003, p.20)

- 3. King Ekathat (also known as King Suriyamarin Throne)

He was the son of King Boromkot, born to Somdet Phanwas Noi. Later, he was promoted to Krom Khun Anurak Montri. He was the elder brother of King Utumphon, who abdicated the throne after ruling for just over three months. Prince Ekathat was crowned king at the age of 40, taking the full title: Phra Bat Somdet Phra Si Sanphet Borommarachamaharat Boworn Sujarit Thotsaphit Thammaret Chetthalok Nayok Udom Boromnarad Phon. He was the last king of the Ayutthaya Kingdom. Common people called him “Khun Luang Khi Ruad” (the leprous prince) because he suffered from a chronic skin disease, believed to be leprosy or a similar skin condition. His reputation was mostly negative due to poor conduct, which caused him to lose the respect and faith of his people.

Shortly afterward, Krom Muen Thepphiphit, who had become a monk, along with Phraya Aphairacha and Phraya Ratchaburi (Phraya Phetchaburi – S. Phlaynoi, 2003: 150-153, as stated in the Encyclopedia of Thai History), conspired to invite King Utumphon to resume the throne as before. They sent a petition to King Utumphon, who then informed his elder brother (King Ekathat). However, King Utumphon, now a monk, pleaded that no bloodshed occur against those who harbored ill intentions. As a result, King Ekathat exiled Krom Muen Thepphiphit to Lanka (Ceylon or present-day Sri Lanka), while imprisoning the officials involved in the conspiracy.

Since King Ekathat took the throne, the officials were thrown into chaos. Some even quit their posts. A French missionary wrote at that time:

“… The country was in turmoil because the Inner Court (the royal consorts) held power equal to the king. Anyone guilty of rebellion, murder, or arson should have been executed, but because of the greed of the Inner Court, punishments were reduced to confiscation of property — and everything seized went to the Inner Court. (According to Burmese chronicles, King Ekathat had 4 queens, 869 concubines, and over 30 royal relatives [Khajorn Sukphanich, 2002: 269]). The officials, seeing this greed, scrambled to milk as much benefit from the accused as possible so they could get a share. This only deepened the suffering of the people…” Seeing their superiors act this way, lower officials followed suit. Corruption, extortion, and injustice were everywhere. If you had money, you could buy your way out of trouble. The people were left helpless, losing faith and unity because justice was dead. Government officials and citizens lost all morale. When the Burmese finally attacked Ayutthaya in 1767 (B.E. 2310), King Ekathat fled secretly by boat with his servants. But the Burmese found him hiding at Ban Chik near Wat Sangkhawat. After starving for over 10 days, he died at the camp at Pho Sam Ton. The Royal Chronicles written by royal hand mentioned that soldiers found the king’s body in bushes near Ban Chik. He died from starvation, and they planned to bring his remains back to the city for cremation after the war ended (Pramin Kruathong, 2002: 36). Chusiri Jamman (1984: 64) and Khajorn Sukphanich (2002: 269) wrote:

“… Burmese records say the Thai king, his queens, and royal children tried to escape through the western city gate (some say the western gate of the Grand Palace). The king was accidentally shot by a stray bullet and died…”

The Burmese Chronicles recorded that the Burmese army entered the royal city around 4 a.m. on Thursday, the 11th day of the waxing moon in April, B.E. 2310 (1767), corresponding to the year 1129 of the Burmese era. Upon entering the royal city, the Burmese burned down houses and temples completely, and seized countless valuables as well as captured male and female prisoners.

When King Ekathat saw the city fall, he disguised himself along with the royal family and fled through the western gate—the same time Burmese troops were storming in. Chaos erupted. King Ekathat died by suicide right there, but no one knew of his death until the next day. The Burmese soldiers then captured Prince Sosan, a younger brother of Ekathat, who during the war was punished by being chained like a beast because he was recognized. Eventually, they found the king’s body at the western gate and brought it back for cremation. (Sunet Chutintharanon, 1998: 68)

M. Turpin (translated by S. Siwarak, 1967: 57) stated, “The king tried to escape, but someone recognized him, and he was executed right at the palace gate.”

The Burmese chronicle Hoke Kyawe aligns with Thai sources. The Kham Khwaeng Chao Krung Kao (The Ayutthaya Chronicle) states that King Ekathat hid for about eleven or twelve days before passing away. (Rong Siamanon, 1984: 43, from the Historical Report Year 18, Vol. 1, January–December 1984)

Somporn Thepsitha (1997: 31) wrote that King Ekathat fled from the Burmese and hid in a forest outside the city, where he died in hiding. The Burmese found his royal garments and crown, and brought his body to Nemyo Sihabodi, who ordered the king’s body to be buried. Suki Phra Nayok later moved the remains to be buried at Khok Phra Meru, in front of the Wiharn Si Sanphet. (However, Ruamsak Chaikommin, 1994: 18–20, states the burial was in front of the Phra Mongkhon Bophit temple.) Later, King Taksin the Great ordered the exhumation and cremation of the royal remains. (Foundation for the Conservation of Ancient Monuments in the Former Palace, 2000: 162)

Note:

The Throne Hall called Suriya Marinthorn (also spelled Suriya Samrin)—both names refer to the same building—was commented on by King Chulalongkorn (Rama V) in one passage about the royal palaces of the old capital: “The name Phra Thinang Suriya Marinthorn first appeared during the reign of King Phetracha, when the royal remains of King Narai were brought down from Lopburi and enshrined there. At that time, there were three main buildings: the Viharn of King Sanphet, Prasat Benjarat, and Maha Prasat. The names of the first two remain to this day. It should be understood that Phra Thinang Benjarat was later renamed Phra Thinang Suriya Marinthorn because it is located by the riverbank, and the royal coffin was brought there by boat. The name Phra Thinang Suriya Samrin appeared later during the reign of King Borommakot. The change from Suriya Marinthorn to Suriya Samrin was likely made by King Borommakot to make the names of the three throne halls harmonize.” Later, when King Ekathat resided in this throne hall and ascended the throne, the Royal Chronicles referred to it as Somdet Phra Thinang Suriya Samrin. (S. Playnoi, 2003: 406-407)

2.6 How was Ayutthaya before it fell to Burma?

First, understand the main reasons why Ayutthaya weakened before its fall, which include:

1. Weakness in Ayutthaya’s defense system due to royal family divisions The royal family was divided and fought over the throne, splitting into factions. It started during the reign of King Songtham (reigned 1628–1630), who seized the throne from Prince Sri Saowaphak (died 1620). During this conflict, many nobles were killed.

Later, in the reign of King Prasat Thong (reigned 1629–1688), nobles loyal to the previous King Chetthathirat (reigned 1628–1630) were killed, though fewer in number. By the reign of King Narai the Great (reigned 1656–1688), nobles loyal to Prince Chai and King Sri Suthammaracha were almost entirely eliminated. This caused the king to rely on foreign and non-royal nobles, such as Indian, Lao, and European officials like Phraya Ram Decho, Phraya Ratchawangsan, Phraya Siharajdecho, and Chaophraya Witchayen. During King Narai’s illness while staying at the Lopburi palace, Phetracha and Khun Luang Sorasak began purging members of the royal family and both Thai and foreign officials who were their rivals or favored the French. During King Phetracha’s reign (1688–1703), he appointed Princess Srisuwan as royal consort and set Princess Yothathip and Princess Yothatep (daughters of King Narai) as consorts on the right and left sides, respectively. After elevating his previous wife to the central queen, when the two new consorts bore sons each, King Phetracha favored and honored these princes as they were grandsons of King Narai, who was widely respected by officials. Although Khun Luang Sorasak remained as Maha Uparat (viceroy), he was suspicious of these princes, especially one named Chaophraya Khwan. Another prince, Pratsonoi, was raised near Wat Phutthaisawan. At age 13, he was ordained as a novice monk for 5 years, studying Buddhist teachings. After leaving monkhood, he studied other sciences and was later fully ordained as a monk to avoid political danger. During King Phetracha’s reign, campaigns to capture Nakhon Si Thammarat and Nakhon Ratchasima led to many capable military nobles dying in battle.

Wat Phutthaisawan

Although the reign of King Sanphet VIII (Phra Chao Suea) lasted only 6 years (A.D. 1703–1708 / B.E. 2246–2251), and the reign of King Phumintharacha, also known as King Borommakot (Phra Chao Yu Hua Thai Sra) (A.D. 1708–1752 / B.E. 2251–2275), lasted for 24 years, together spanning 30 years, there were no major wars with foreign countries during that time. However, near the end of King Phumintharacha’s reign, internal conflict arose: Prince Aphai and Prince Paramet, his sons, fought against the Uparaja (viceroy), Prince Phon, their uncle. The latter emerged victorious and ascended the throne as Borommarachathirat III, but Thai historians gave him the name King Borommakot, possibly because he was the last king of Ayutthaya whose royal remains were enshrined in a Borommakot (royal urn) — a reflection offered by Professor M.C. Subhadradis Diskul.

During this reign, the kingdom prospered in many aspects and grew wealthy through trade. However, internal conflict erupted once again. Near the end of the reign, the king’s three sons presented a formal complaint, accusing Prince Thammathibet, the Uparaja (viceroy), of having an illicit relationship with Princess Sangwan, a royal consort and daughter of King Phumintharacha. Upon investigation, the accusation was found to be true, and both were punished by royal decree and consequently died.

As for King Ekkathat, before ascending the throne, he was known as Prince Anurak Montri. His father, King Borommakot, was fully aware that this son was not suited to be king. When the first appointed Uparaja (viceroy) was punished and passed away, the king chose to appoint his third son, Prince Uthumphon, as the new Uparaja instead. However, after King Borommakot’s reign ended and Prince Uthumphon had been crowned king for less than three months, Prince Ekkathat (Anurak Montri) declared himself king as well. The king’s three sons—Prince Chitsunthon, Prince Sunthorn Thep, and Prince Sepphakdi—were displeased and plotted rebellion, but they were caught and executed.

Prince Uthumphon, who shared the same mother as Ekkathat, made a personal decision—perhaps also due to his peaceful disposition—to abdicate and ordain as a monk. In truth, this decision contributed to the neglect of state affairs, which allowed the Burmese invaders to recognize the kingdom’s vulnerability and seize the opportunity to attack. When the first Burmese invasion occurred in 1759 (B.E. 2302), Prince Uthumphon recognized his duty and agreed to leave the monkhood at the request of senior officials in order to help lead the defense of the kingdom. But after five years of peace, when King Ekkathat once again claimed the throne, Prince Uthumphon permanently withdrew from worldly affairs, returning to monkhood and refusing to leave again, even when Ayutthaya fell to the Burmese in 1767 (B.E. 2310).

Prince Uthumphon’s conduct, which earned him the nickname “Khun Luang Ha Wat” (The Royal Who Clung to the Monastery), played a part in the downfall of Ayutthaya. Had he not been overly peaceful and instead accepted the truth that his elder brother was unfit to rule during such a time of national crisis, the flaws in governance might have been addressed during the five-year window (1759–1764). But due to the inevitable fall of Ayutthaya, King Ekkathat bore the disgrace of having brought ruin to the kingdom, as he indulged in personal pleasures and failed to fulfill the responsibilities of a true leader.

“Khun Luang Ha Wat” (Prince Uthumphon) eventually lost all interest in state affairs and focused solely on religious practice. In conclusion, those who held the position of national leader failed to fulfill their duties: one was completely incompetent and incapable of ruling, while the other, driven by misplaced affection for his elder brother and an overwhelming devotion to the spiritual path, had entirely lost concern for the nation’s worsening crisis.

It may be said that during the Ban Phlu Luang dynasty, although the kingdom experienced over 60 years of peace from foreign wars, the constant rebellions, distrust, and suspicions among royal relatives—stemming from disunity within the royal family and court officials—became one of the primary causes of Ayutthaya’s decline.

In summary, during the rule of the Ban Phlu Luang dynasty, Ayutthaya’s political stability was weakened by power struggles between nobles and the monarchy. The nobles’ influence in the provinces grew rapidly, prompting the central government to diminish their power through suppression and oppression—including enforcing rules that forbade governors from communicating with one another—to prevent any single governor from amassing enough strength to rebel against the capital. However, rendering the provinces ineffective was essentially the same as destroying Ayutthaya’s own defense system. The kingdom could no longer mobilize troops from the weakened provinces to protect the capital. When the Burmese army approached, the Thai forces failed to stop them from advancing. Most people lacked the morale or will to fight seriously, resulting in mass desertions, widespread confusion, and chaos. (Chusiri Chamornman, 1984: pp. 56–58)

Living in Complacency — That is to say, from the monarch down to the officials both in the capital and the provinces, as well as the general populace (with the exception of a few minority groups), all lived in a state of complacency. Most citizens sought only personal comfort and pleasure, while the ministers neglected to maintain or defend the kingdom.

When King Alaungpaya of Burma waged war to consolidate the Mon territories and pursued the Mon people across the Thai border into the southwestern region of Siam in March 1759 (B.E. 2302), the campaign began with the capture of Mergui (a port city of the Ayutthaya Kingdom), Tavoy, and Tenasserim—without any resistance from the Siamese side. He then led his army across the mountains and along the coastline, capturing Kui Buri, Pranburi, Phetchaburi, and Ratchaburi, eventually advancing northward through Suphanburi to lay siege to Ayutthaya for two to three months. The Ayutthaya Kingdom offered very little resistance, mainly due to sheer negligence. After decades without foreign war, the kingdom had grown complacent, failing to maintain its military forces or train soldiers for future conflict. The able-bodied men had likely lost all enthusiasm for military service.

Before King Alaungpaya of Burma could even cross into Siamese territory, he passed away. After that, his eldest son ascended the throne. According to Thai records, his name was Manglok, though the Burmese referred to him as Naungdawgyi. He reigned for only three years before his death. During his short reign, he was preoccupied with quelling internal rebellions from royal relatives and power struggles among regional rulers. These conflicts were not yet fully resolved when he passed away in November 1763 (B.E. 2306). His younger brother, known in Thai sources as Mangra and in Burmese as Ma Yadu Meng (more famously known by the title Hsinbyushin), succeeded him. During the early years of his reign, he was still consolidating his rule and organizing the state, so Thailand did not face Burmese invasion for five years. However, Siam became complacent. King Ekkathat did not reform or strengthen the military. There is no record of efforts to recruit or appoint competent generals or officers, and even basic military training was neglected. Weapon stockpiles were not replenished, despite centuries of previous arms trade and training from Western nations like Portugal (who had taught cannon use to Siam), England, the Netherlands, and France, who continued to send missionaries and merchants. According to correspondence and historical records from French missionaries and Dutch traders—translated and compiled in Thai in the Chronicles Volume 39 by the Fine Arts Department—it is noted that: “King Ekkathat, unable to find capable Thai military leaders to defend the kingdom, had to rely on foreign assistance. However, these foreigners were not soldiers, so they could only offer limited help. Weapons were scarce, and rebellions frequently broke out in the provinces. When suppressed, the rebels were executed, further weakening the kingdom’s military strength.” Instead of addressing the causes of rebellion or improving national defense, these actions were short-sighted and reactive. There was no strategic planning for governance or safeguarding the kingdom.

When the officials realized that the king was lacking in capability, they should have helped in some way—such as promoting military training or finding ways to respectfully petition for preparations to defend the kingdom. The Burmese attitude when Mangra (King Hsinbyushin) ascended the throne clearly showed that he was gathering strength and consolidating power, just like his father, King Alaungpaya. It was well known that he had once led the siege of Ayutthaya alongside his father and thus knew the Thai border areas well, including the weaknesses in Thai military skills. The Thais ought to have prepared by improving their forces, training, battle tactics, and weapon usage to be more effective in warfare. But instead, we were recklessly negligent without any excuse.

Although the Burmese king (King Mangra) did not personally lead the army like King Alaungpaya did, he knew the shortcut route through western Thailand and sent his troops along the same path used in 1763 (B.E. 2306). Meanwhile, the Siamese did not prepare any forces to resist the Burmese at all—showing blatant carelessness. The Burmese marched in easily, crossing Thai territory and capturing cities until they reached Ratchaburi, where they rested for four days. When the Siamese sent scouts, they clashed with the Burmese troops. According to Burmese records, the Burmese commander was named Yazawunthan. Later, when the Siamese tried to resist, their weapons were inadequate, and their officers and soldiers lacked proper training, so they were defeated. Despite being poorly armed and outnumbered, the local Siamese villagers—like those from Wiset Chai Chan and Bang Rachan—fought fiercely and resisted the Burmese. The Burmese had to resort to various tricks, but eventually, the villagers were defeated, sacrificing their lives completely.

Note: The Heroic Deeds of the People of Bang Rachan

In the year 1764 (B.E. 2307), the Burmese army invaded Siam to scout the area because of the political transition in Siam. The Burmese advanced as far as Suphanburi and Singburi provinces. However, the Siamese army under King Ekathat had not yet deployed to resist the enemy. As a result, the Burmese army proceeded to Bang Rachan village (in present-day Singburi province).

Bang Rachan Village Monument

Bang Rachan Camp

(Image from Rattanakosin Sculptural Album and Central Thai Cultural Encyclopedia, Vol. 3)

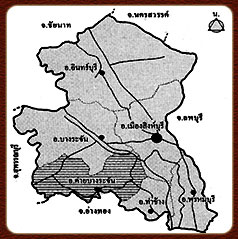

A brief location map showing the position of Bang Rachan Camp District, Sing Buri Province

(Image from Central Thai Cultural Encyclopedia, Volume 3 — Banana Bat, Chinese Opera Paintings)

The villagers of Bang Rachan and the people of Mueang Sankh joined forces under the leadership of Phra Kru Tham Choti and 11 village heads as follows:

Mr. Thaen, villager of Si Bua Thong, Mueang Sing Buri

Mr. In, villager of Si Bua Thong, Mueang Sing Buri

Mr. Mueang, villager of Si Bua Thong, Mueang Sing Buri

Mr. Chot, villager of Si Bua Thong, Mueang Sing Buri

Mr. Dok, villager of Krab, Mueang Wiset Chai Chan

Mr. Thong Kaew, villager of Pho Thale, Mueang Wiset Chai Chan

Khun Sank Sanpakit (Thanong), official of Mueang Sankh Buri

Mr. Phan Rueang, headman of Bang Rachan subdistrict

Mr. Thong Saeng Yai, assistant headman of Bang Rachan subdistrict

Mr. Chan Khiao or Chan Nuad Khiao, village head of Pho Thale

Mr. Thong Men, village head

The villagers of Bang Rachan fought the Burmese enemy with bravery and determination seven times. In the final battle, the Burmese sent Suki, a Mon officer who had once lived in Thailand and knew the area well, to attack Bang Rachan Camp. He led troops using cannons to bombard the camp relentlessly, causing many villagers to be wounded and killed daily. Khun San then led some villagers to Ayutthaya to request cannons from the king to fight the Burmese. However, the Minister of Defense advised against granting the request, fearing the cannons might be captured by the Burmese and used to bombard Ayutthaya itself. Phra Ajarn Tham Chot from Wat Khao Bang Buat took charge of casting cannons twice, but both times the cannons broke and were unusable. On the third attempt, the cannon fired only once before it exploded. With no other options, the villagers gathered the children and weaker women, loading them onto carts to secretly escape the danger through the rear of the camp.

At dawn, after having their final meal, the villagers of Bang Rachan bravely charged out of the camp to fight the enemy, showing no fear of death. Suki, the Mon commander, ordered the cannons to fire at the villagers, tearing them apart. The survivors broke through the cannon fire to continue fighting against the much stronger Burmese forces, but all eventually died, blood soaking the land of Thailand. Bang Rachan Camp was destroyed on Monday, the 2nd waning day of the 8th lunar month in the Year of the Dog. After five months of fighting, the Burmese finally managed to besiege Ayutthaya. (Somphon Thepsittha, 1997: 19-20)

Later, the patriots of Singburi province, along with the Thai people, united to build a monument to honor the bravery, patriotism, and sacrifice of their ancestors. His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej graciously presided over the opening ceremony on Thursday, July 29, 1976. Every year on February 4th, the government designates a commemorative day to pay tribute to the heroic deeds of these warriors. (http://kanchanapisek.or.th/kp8/sbr/sbr203.html, July 15, 2004)

Another reason for the mess was that the Thais just weren’t ready to fight to defend their country. They ignored the lessons from the time the Burmese besieged Ayutthaya during King Alon Paya’s reign — how the Burmese used brutal tactics like firing cannons up close and even went so far as to farm the land to stockpile supplies. But the Thais were careless, didn’t cut off the Burmese from farming, and didn’t prep big food reserves in advance. They just kept believing the old myth that when the flood season came, the Burmese would pack up and leave. But nope. The Burmese stayed planted for over half a year, brought in boats, and farmed themselves. Meanwhile, the Thais stubbornly focused only on defending Ayutthaya city, leaving the outlying towns to rot. Even skilled military leaders like Phraya Tak and others were called into the city to fight, but they had to operate under the strict orders of the king, who clearly didn’t know how to command an army. No matter how talented the generals were, they couldn’t stand up to the Burmese. Plus, harsh punishments kept the provincial nobles from raising their own troops to help unless ordered. Still, after Ayutthaya fell in early 1767, skilled leaders in the north, south, and northeast started gathering forces into various factions — many with ambitions beyond just reclaiming freedom (but not all). (Chusiri Jamraman, 1984: 58-60)

- 3. Inefficient Systems of Ayutthaya

At least two major issues stand out: the disorderly system of commoners (ไพร่) and serious flaws in intelligence gathering (ข่าว). (Foundation for the Conservation of Ancient Monuments in the Old Palace, 2000: 33-34)

3.1 Disorder in the Corvée System

The royal court lost a ton of manpower to nobles and provincial governors, who avoided registering their people with the central authority. This made organizing the army a real pain, with fewer troops than needed. Because of this, they couldn’t send a strong enough force to block the Burmese armies passing through the frontier towns.

3.2 Flaws in Intelligence

Bad intel messed up the Thai army’s ability to track Burmese troop movements. The Thais had to split their forces to fight the Burmese in multiple places, spreading their troops thin and weak. As a result, the Thai army kept getting smashed and retreating back to Ayutthaya every time they faced the Burmese.

The chaos, disorder, and weakness that happened during Ayutthaya’s collapse weren’t just because of bad leadership — that’s only part of it. You could even say Ayutthaya never really had a fair shot at fighting off its enemies the way a kingdom should.

- 4. The Cunning Plan of the Burmese to Conquer Ayutthaya

The Burmese planned their conquest of Ayutthaya with serious strategy. They sent armies to surround the city from both the north and the south, waging guerrilla-style warfare for three years, attacking various towns. The northern and southern forces finally joined at the end of 1765. The Burmese laid siege to Ayutthaya until 1767. On April 8, 1767, the city walls of Ayutthaya were breached. The Burmese army stormed in, capturing people and looting treasures, burning down the city and its temples. But the destruction wasn’t just physical — they also targeted the city’s spiritual and sacred symbols, the very essence that gave the people hope and identity. In other words, they destroyed the city’s “soul” to make sure Ayutthaya could never rise again. This fall wasn’t simply about one kingdom losing independence to another. It was the complete collapse of a once-glorious kingdom, leaving behind only its name for future generations to remember. From the Foundation for the Conservation of the Old Palace, 2000 (2543 BE)

Paradee Mahakhan (1983: 11-12) summarized the causes of Ayutthaya’s decline as follows:

- Instability of the Monarchy Institution Although, in theory, the kings of Ayutthaya were absolute monarchs — the supreme rulers of life and land — in practice, very few kings managed to maintain that power firmly. Throughout Ayutthaya’s 417-year history, power struggles and throne conflicts were constant. Only about 20 kings managed to keep the throne without being overthrown or forced to abdicate. For an absolute monarchy, this instability within the royal institution meant political instability inside the kingdom itself.

2. Internal Conflicts Among the Ruling Class in the Ayutthaya Kingdom The ruling class was torn apart by conflicts everywhere — between kings and royal family members, between different branches of the royal family, between nobles and kings, between nobles and royals, and even nobles fighting among themselves. These constant power struggles seriously messed up how efficiently the kingdom was run, wrecked the economy’s stability, and crippled their ability to defend the country and keep the kingdom safe.

3. The whole system sucked at controlling manpower and managing the kingdom’s territory. Chaos and rebellions popped up all the damn time, seriously weakening the kingdom’s power and stability.

4. The enemy was way stronger and already figured out how to counter the strategies that Ayutthaya used to rely on.

Because of all these reasons, Ayutthaya couldn’t hold its ground and ended up falling to the Burmese on April 8, 1767 (B.E. 2310).

Major General Janya Prachitromron (1993: 193-194) summarized the causes of the fall of Ayutthaya to the Burmese as follows:

King Ekathat was a weak monarch lacking wisdom and capability. His nine-year reign was a complete failure in governing the kingdom.

The country deteriorated due to struggles for the throne, what we now call a coup d’état, not a revolution, as the absolute monarchy system remained unchanged.

The royal family lacked unity, each aiming for power rather than cooperating in governance. They barely participated in administration except when war approached Ayutthaya. During King Ekathat’s reign, officials were frequently divided.

The rulers of the Ban Phlu Luang dynasty hardly developed the country. Agriculture, the main occupation of the people, was neglected, and trade continued as it had been before without improvement.

If the Alompaya dynasty, especially King Mangrai, had not ruled Burma, Ayutthaya might have avoided invasion and loss to the Burmese enemy. Mangrai was determined to capture Ayutthaya. The kingdom likely knew this and tried to strengthen city defenses and accumulate weapons but apparently did not have enough funds for these expenses.

NOTE:

Long poem predicting the fate of Ayutthaya

It speaks of the city of Ayutthaya,

A kingdom of gems, royal faith,

A supreme and glorious realm,

Praised in every place and land.

Every province, border, and region,

Merchants and traders from all corners,

Speaking twelve different tongues,

All come to seek refuge in Ayutthaya.

The people live free from harm,

Neither madness nor suffering,

While the great king reigns,

Ruling the domain in peace.

With royal edicts, justice prevails,

Bringing prosperity and well-being.

A home for all under the sky,

A shelter for all gods and stars.

All subjects, nobles, priests, and elders,

Like a grand pavilion to reside in,

Like the shade of the Bodhi tree,

Like the sacred river Ganges,

A cherished refuge in times of drought.

By the power of the king’s might,

Enemies from all directions are subdued.

Tributes come from all lands,

Showing homage and respect.

Ayutthaya is flourishing,

Its glory ever expanding,

Abundant happiness in every land,

Marking the year two thousand in the cycle.

But then beasts and creatures,

Will surely bring danger and harm,

Because the great king will fail to practice,

The ten royal virtues as he should.

This leads to sixteen great wonders:

Stars, moon, earth, and sky bring omens,

Disasters spread in every direction.

Great clouds burn like black fire,

Ominous signs cover the city.

The river turns bloody like red blood,

The earth’s heart goes mad, the sky turns yellow,

Forest spirits invade the city,

City spirits flee into the wilderness.

The city’s protector abandons his post,

Dark spirits enter as rulers,

The earth mourns and beats its chest,

The dark heart burns to ashes.

In a prophecy foretold, not once mistaken,

Look closely, and the truth is shaken.

Not the season of heat, yet heat blazes loud,

Not the season of wind, yet gusts howl proud.

Not the cold season, but cold grips tight,

Calamities spread, chaos ignites.

The guardians of the Dharma, the sacred way,

Protect only those who’ve lost their way.

Good men fall prey to wicked foes,

Friends betray love and cause their woes.

Wives slay their husbands’ worth,

The wicked purge those of noble birth.

Disciples rise against their masters’ will,

Youth dare to humble elders still.

The righteous lose their rightful power,

Wise men fall low in their darkest hour.

Tiles rise and float without a place,

Gourds adrift retreat without trace.

Noble clans face ruin’s claim,

While lowly scum feast on their shame.

Virtuous men lose their minds and ways,

Joining schemes of deceitful plays.

The king’s reign shall fall to ruin’s hand,

The nation stripped of honor and stand.

Beasts of chaos grow bold and free,

The sacred teachings fade to debris.

The brave lose courage’s flame,

Knowledge and skills disappear in shame.

The wealthy fall from fortune’s grace,

Villains lose all sense of face.

Lifespans shrink, months and years,

Morals twist, disorder nears.

Crops wither, fruits lose their taste,

Herbs and roots decay in waste.

Once-blessed wonders fade away,

Fragrant plants lose scent day by day.

Rice turns scarce, betel grows dear,

Drought and famine strike severe.

Plagues arise, strange and wild,

Ghostly hordes deceive and beguile.

The capital city, once so grand,

Faces chaos sweeping the land.

Souls grow distant, troops lose heart,

Men and women torn apart.

Priests, nobles, common folk in pain,

Suffering endless, a world insane.

Battles rage, blood will spill,

Death and ruin bend all will.

Even the waterways will dry up like land,

Cities and palaces grow wild, like forests of tigers stand.

All kinds of animals, flesh and bone,

Will vanish, leaving the land alone.

All creatures, every kind and race,

Will perish, vanish without a trace.

The terrible god of death will ravage the land,

Destroying all with war’s harsh hand.

Ayutthaya will fall and fade away,

Its three great jewels lost someday.

Through years, months, nights, and days,

Its name and era will cease to stay.

Once Ayutthaya thrived in bliss,

A heavenly city of endless happiness.

But it will become a place of sin and shame,

Fading away, forgotten, lost in name.

(Copied from http://www.pantip.com/cafe/writer/topic/W2537795/W2537795.html, 1/9/2547)

The Prophetic Long Poem of Ayutthaya

At that time, all creatures great and small

Shall face great peril, certain and severe.

For those in power lack the Tenfold Kingly Law,

Thus calamities will rise, sixteen in number, clear.

The stars, the moon, the earth, and sky shall turn strange,

Disasters shall strike in every direction wide.

Great clouds shall burst into black fire’s range,

And ominous signs shall rise in every countryside.

The sacred river will run red, like a bird’s blood spilled,

The earth shall rage, the sky turn yellow, ill.

Forest spirits will rush to possess the town,

While city spirits flee to the wilds, unbound.

The Guardian Spirit of the City shall flee in dread,

While the Demon of Death takes root instead.

The Earth Goddess shall weep and beat her chest,

As the Demon’s heart burns within his breast.

As foretold, the prophecy shall not go astray,

When one reflects, it all aligns this way.

Though not the season, heat shall scorch the land,

Though not the season of rain, storms shall rise,

All trees and grasses meet their sad demise.

Disasters spread beneath all earthly skies.

Even the deities who guard the holy way

Will turn to shield the wicked in dismay.

The virtuous shall fall to the vile and base,

And friendship’s love shall vanish without trace.

Wives will scorn the grace their husbands gave,

The wicked shall strike down the wise and brave.

Students shall rise against their teachers’ rule,

The young shall dare to mock the old as fools.

Those with virtue will lose their power,

The wise will fall into decline,

Tiles will loosen and float away,

The small gourd will sink and fade.

Noble lineages will vanish and fade,

Because the lowly have come to invade.

The virtuous will lose their calm and grace,

Entangled in deceit’s cruel embrace.

The great king will lose his might,

The vassal states will lose their rank,

The beasts will roam wild and fierce,

The Dharma will grow obscure and dark.

The brave will lose their courage,

All knowledge will vanish in silence.

The wealthy will lose their fortunes,

The wicked will be stripped of kindness.

Lifespans will shorten, shifting with the years,

Customs will falter, as fate appears.

Crops will wither across the land,

Fruits and roots lose taste as planned.

All medicines, herbs, and rare plants will spoil,

Their once great powers now fade and recoil.

Fragrant flowers and trees of sweet delight,

Will dwindle and fade as fades the night.

Rice will be scarce, areca nuts expensive,

All kinds of crops will suffer drought and absence.

Poisons and plagues without warning will rise,

Ghostly hordes will run, disguised as guise.

The capital city of the kingdom,