King Taksin the Great

Chapter 8: King Taksin Ascends the Throne at Thonburi

A mural depicting King Taksin ascending the throne at Thonburi (courtesy of Muang Boran)

A mural depicting King Taksin ascending the throne at Thonburi (from the book King Taksin the Great)

8.1 Why did King Taksin not reign at Ayutthaya?

When Chao Tak completed the cremation of King Ekkathat, he wished to restore Ayutthaya as the royal capital as before. He mounted the royal elephant to survey the area of the palace and traveled through the city. He saw that the great and small palace buildings, the monasteries and vihara, and the dwellings of the people had been largely burned and destroyed by the enemy. Very few places remained in good condition, which filled him with sorrow.

That night he stayed at the San Chai Throne Hall, the audience hall formerly used at the rear of the palace. Chao Tak dreamed that the former kings drove him away and would not allow him to remain. At dawn he related the dream to all the officials and said: “We feel great pity and see that the city will become deserted and overgrown. We have come to restore and support it to its former completeness. But when the former owners still guard it jealously like this, let us go and build a city at Thonburi instead.”

Wina Rojanaratha (2540: 91) commented on the telling of the dream that “such narration may have been a profound psychological device of King Tak, for relocating the capital from Ayutthaya to Thonburi at that time was reasonable for many causes.”

Chao Tak possessed a noble virtue: exceptional ability as a leader who listened to the views of others and of the people at large. He understood well that all Thai subjects still respected the royal lineage of Ayutthaya, and that their sentiments remained strongly tied to the former capital. Yet the circumstances at that time were utterly unsuitable. Therefore he sought to persuade the people indirectly through various reasons, for he was an outstanding psychologist.

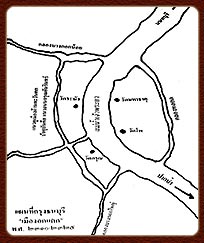

Map of Ayutthaya (from the book Ayutthaya)

Map of the Royal Palace

(Image from the book Ayutthaya)

The reason King Taksin did not establish the capital at the old city was that Ayutthaya was vast. The royal palace had five tall and grand halls, and the temples and monasteries were all large. When the city had been largely burned and destroyed by the Burmese invaders and corrupt officials, Chao Tak, having only recently gathered his forces and restored his position, could not have the resources to repair such a large city and restore it as the royal capital. Moreover, if enemies invaded, there would not be enough troops to defend the fortifications, as the people were scattered in all directions and could not be gathered effectively (Royal Chronicles of the Old Capital: 70).

Regarding King Taksin’s relocation of the capital from Ayutthaya to Thonburi, Somdet Phra Borommaratchathera Krom Phraya Damrong Rajanubhab commented, “When considering the events recorded in later chronicles, it is seen that Chao Tak’s establishment of Thonburi as the capital was entirely practical. If the former king had come to prevent Chao Tak from settling in Ayutthaya, he did so with goodwill, warning him to avoid mistakes out of pride. Although Ayutthaya had a strategic location surrounded by rivers and strong fortifications, Chao Tak’s forces were insufficient to defend it against enemies, including the Burmese and other Thai factions, who could attack at any time. Ayutthaya’s location allowed easy access by land and water, so establishing the capital there with insufficient forces would have been dangerous. By setting the capital at Thonburi, not far from Ayutthaya, his authority was effectively as if it were in Ayutthaya, but with the advantage of Thonburi being on a deep river near the sea. Even if enemies approached by land without naval forces, it would be difficult to attack Thonburi. The city had fortifications, and its smaller size allowed Chao Tak’s army and navy to defend it. If it became indefensible, being near the river mouth allowed retreat by ship back to Chanthaburi. Strategically, establishing Thonburi was advantageous. Politically, it was also important, as Thonburi controlled the river mouth through which northern provinces traded with foreign countries, similar to Ayutthaya, preventing northern provinces aligned with other factions from obtaining military supplies abroad while allowing Chao Tak to access them easily.

For these reasons, establishing the capital at Thonburi allowed Chao Tak to assert authority over the northern provinces. Seeing these benefits, he chose Thonburi as the royal capital, and his decision was sound” (Thuan Boonyaniyom, 1970: 67-68).

In summary, the reason for not restoring Ayutthaya as the capital was

- 1. Chao Tak’s limited forces were insufficient to defend Ayutthaya, which was a large city.

- 2. Ayutthaya’s location allowed enemies to approach easily by both land and water, so with inadequate forces, it would have been dangerous to remain there.

- 3. Ayutthaya was so dilapidated that there was barely enough capacity to restore it in a short time, and both manpower and resources were lacking.

- 4. The enemies (Burmese) already knew the terrain and access points to attack Ayutthaya, as well as its strategic weaknesses, putting the city at a defensive disadvantage.

- 5. The supply routes from the provinces to Ayutthaya by land were unsafe (Sanun Silakorn, 1988: 11).

Wat Phra Si Sanphet before restoration, with the Vihara of Phra Mongkhon Bophit visible in the distance. Photograph from the time of World War II, 1945 (from the book Ayutthaya).

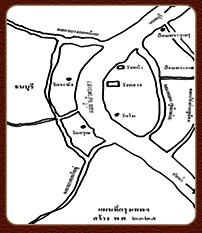

Map of Thonburi city

(from the book Wiang Wang Phang Thon: Siamese Communities)

Wat Phra Si Sanphet after restoration.

(from the book Wiang Wang Phang Thon: Siamese Communities)

In summary, the reasons for establishing Thonburi as the capital were as follows:

- 1. Thonburi was located near Ayutthaya, which had just been recaptured from the Burmese (who had stationed troops at the Pho Sam Ton camp), making it convenient to guard against other factions attempting to dominate Ayutthaya.

- 2. Thonburi was situated on deep water near the sea, so if enemies approached by land without naval support, it would be difficult for them to succeed in an attack.

- 3. Thonburi was a smaller city with suitable terrain for establishing a new capital, manageable for Chao Tak’s army and navy to defend, and its small size suited a population of limited numbers.

- 4. Thonburi had fortifications on both sides of the river, namely Wichaiprasit Fort (sometimes referred to as Wichai Prasit) and Wichaiyent Fort, convenient for defending against enemy naval attacks or sieges. Wichaiprasit Fort was in a condition that could be occupied immediately without extensive repairs, suitable for Chao Tak’s forces.

- 5. It was very difficult to besiege Thonburi if the enemy did not have strong naval forces.

- 6. If, for any reason, the city could not be defended, Thonburi’s proximity to the river mouth allowed retreat by ship back to Chanthaburi or other coastal cities temporarily and conveniently.

- 7. Thonburi had strategic importance as it controlled the river mouth, blocking northern provinces from trading with foreign countries, similar to Ayutthaya, preventing powerful northern provinces from acquiring weapons and military supplies from abroad.

- 8. Thonburi was also economically important, being close to the sea, convenient for trade and foreign contact. Additionally, the surrounding plains and nearby provinces were fertile, with clay and alluvial soil suitable for agriculture, such as the areas of Krathum Baen, Nakhon Chai Si, coastal fields, and the Phaya Thai region.

8.2 Originally, King Taksin intended to reside in which city, and why did he change his mind?

At that time, Thonburi had only small forts, and the houses were old and dilapidated with no walls. It would have been more suitable to go to a city with stronger fortifications. In the Royal Chronicles of Thonburi, Phan Chanthanusorn edition (Jeim), it is recorded that originally he intended to go to Chanthaburi, as follows:

“He observed the suffering of the people, who faced death from famine, thieves, and disease, amassed like a mountain. He saw the citizens, starving and emaciated, appearing like loathsome spirits. He felt deep compassion, as if weary of the royal duty, and intended to go to Chanthaburi. The monks, Brahmins, officials, and common people respectfully petitioned him, appealing that for the benefit of his coronation and supreme enlightenment, he should remain. Seeing the merit and necessity, he accepted their request and thus stayed at the palace in Thonburi.”

The term พระตำหนัก (palace or royal residence) seems to be used according to rank or status. According to the history of Wat Arun Ratchawararam, he proceeded by boat along the river and arrived at the temple at dawn. He considered it an auspicious time and had his royal barge moored at the pier. He then went ashore to pay homage to the main stupa at the prang (originally only eight wa high) and subsequently spent the night at the sermon hall near the Bodhi tree.

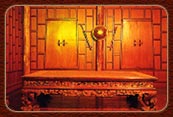

The royal bed platform at Wat Intaram

(from the book Sara Krung Thonburi)

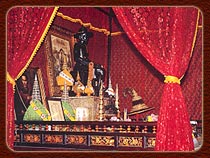

The throne platform in the small vihara of Wat Arun Ratchawararam, decorated with the seasonal motif, gilded in two layers, and carved with putthan flowers.

The royal bed platform is enshrined at the National Museum.

Note: in the royal chronicles the term phra thamnak refers to the sermon hall; this is undoubtedly so, because Wat Makok at that time was a small temple and its kuti and vihara would not have been as large as modern temples. the sermon hall seemed larger and more spacious than the other buildings.

the surviving evidence today is the royal platform, a single plank measuring 17 feet wide and 120 feet long (this platform is now at Wat Arun Ratchawararam). the royal bed platform siha-saiyasana (now at Wat Intaram) is a plank 88 centimeters wide, 5 centimeters thick, and 2 meters 487 centimeters long, decorated with an ivory balustrade. (Suree Phumiphom, 2539: 78)

the reason for intending to go to Chanthaburi appears to have been that Chanthaburi had city walls and its towns were still prosperous; the people there were not suffering starvation as described in the royal chronicle above. but if he had actually gone to Chanthaburi, it would have seemed as though he abandoned the starving people to die, for at that time there was no one to cultivate rice and food was scarce, with sacks of rice selling for three baht, one tamlueng, or five baht per sack.

there were hardly any possessions left among the people, so where would they get money to buy food, and the population numbered more than ten thousand. to abandon them and flee would have caused many to die without remedy. to move weakened people far away would only hasten their deaths and would require additional transport. these problems likely led him to remain at the phra thamnak in Thonburi and to assume responsibility for feeding the large number of people; the Thai-Chinese military and civil officials were each granted a sack of rice from the royal provision, enough for twenty days. (S. Phlaynoi, 2543: 61-62)

8.3 King Taksin was coronated in 1768 (B.E. 2311). His royal title was Somdet Phra Chao Taksin Maharat.

Afterwards, King Taksin brought his troops, families, the common people, and members of the royal lineage. He sent out parties to locate his relatives who had been separated, and those found in Lopburi were brought to Thonburi (Sang Phathnotai, n.d.: 177). The remaining officials from the old capital who were still at the Pho Sam Ton camp were also relocated to Thonburi. He then elevated Thonburi to the status of a capital, naming it Krung Thonburi Si Mahasamut, in B.E. 2311, and built the royal palace at the mouth of Khlong Bangkok Yai (currently under the supervision of the Royal Thai Navy, known as the Former Palace).

Note

Those interested in the royal palace of King Taksin the Great can find further details and conduct additional research from the book Sara Na Ru Krung Thonburi: King Taksin the Great and at the URL: http://www.wangdermpalace.com/, which is under the supervision of the Foundation for the Conservation of Historical Sites in the Former Palace.

The exact date of King Taksin’s coronation remains widely debated among scholars. S. Plai Noi (2003: 122) states, “King Taksin ascended the throne of Thonburi on 28 December 1767 (B.E. 2310).”

The Foundation for the Conservation of Historical Sites in the Former Palace mentions in the book King Taksin the Great (2000: 30), “Tuesday, wan 4 of the first lunar month, Chula Sakarat 1129, corresponding to 28 December 1767 (B.E. 2310).”

Phra Pawarolarnwittaya (1937: 227) notes, “After King Taksin completed the cremation of King Ekkathat, he intended to restore Ayutthaya as the capital. He stayed at the Thong Phuen Throne Hall, where he dreamed that the former king had driven him away. Therefore, he abandoned Ayutthaya and established Thonburi as the capital, building the royal palace between Wat Arun Ratchawararam and Wat Molilok. The Thai-Chinese officials then jointly invited him to become king in 1767 (B.E. 2310), at which time he was 34 years old.”

The commemorative book for the inauguration of King Taksin the Great’s monument in Chanthaburi (1981: 41–42) and Wina Rojanaratha (1997: 92) state, “… since there is no precise historical record of the coronation date, considering the historical events, King Taksin recaptured Ayutthaya from the Burmese in December 1767 (B.E. 2310). After arranging King Ekkathat’s cremation, releasing the captured nobles and Thai people, and improving the living conditions of the populace, as well as relocating the capital to Thonburi, the coronation could only have taken place in 1768 (B.E. 2311). Several primary sources confirm that 1768 (B.E. 2311) was the year Taksin ascended the throne, such as:

The horoscope record in Phra Chao Phongsawadan, Part 8, stating, “Year of the Rat, Chula Sakarat 1130 (B.E. 2311)… on the 3rd day, wan 1, morning hour 1, there was an earthquake. That year Taksin gained the throne at the age of 34.”

The horoscope chronicle by Phra Ya Pramoon Thanarak states, “(During the Thonburi reign) Year of the Rat, Chula Sakarat 1130, Phra Ya Taksin ….” The records of the French missionary group, who arrived during the Ayutthaya period under King Ekkathat, continued through Thonburi and the early Rattanakosin period, appear in Part 6 of Prajum Phongsawadan, Part 39. Monsieur Corr wrote in a letter to Monsieur Brigot, “On the 4th of March this year (2311), I arrived at Bangkok …” and “Upon my arrival at Bangkok, Phra Ya Taksin, the new king, received me most graciously ….”

Nai Suan Mahadlek composed a laudatory poem for King Taksin in B.E. 2314, affirming his coronation:

Who could dare oppose him, confront him?

All armies succumb to his merit.

He was coronated upon the royal throne,

Complete is his sovereignty over the land, as vast as the heavens.

Although it can be concluded that Taksin was coronated and established Thonburi as the capital in B.E. 2311, the exact day and month of his ascension could not be verified. The government therefore designated the first day he appointed officials as the official anniversary of King Taksin’s coronation. As recorded in the Phra Chao Phongsawadan Krung Thonburi (Panchanumas edition, Jeim) :

1

“On the 3rd day, wan 1, Year of the Rat, late afternoon at 7 p.m., there was a lunar eclipse.

On the 3rd day, wan 1, morning hour, he presided over officials, spoke to the people, and instructed the Chinese to sell gold Buddha statues via ships. The king expressed his intent

4

to establish equanimity and the Brahmavihara to uphold Buddhism and care for the people. A remarkable earthquake occurred for a long time.” (Fine Arts Department, Prajum Phongsawadan, Part 65, p. 39, cited by Wina Rojanaratha, 1997: 92)

The 3rd day, wan 1, Year of the Rat, corresponds to Tuesday, 4th wan of the first month, Chula Sakarat 1130, or December 28, 1768.

4

This is also confirmed in Chinese records regarding King Taksin’s coronation and in horoscope chronicles:

“… Year of the Rat, Chula Sakarat 1130. That year Taksin gained the throne at the age of 34” (It is understood that he was not coronated before August 1768, as in that month he sent a royal letter to the emperor in Beijing requesting recognition of his investiture as “Wang” of Siam, signing the letter accordingly).

“‘Kan-en-tsu,’ which corresponds to ‘Kamphaeng Phet,’ was the royal title of His Majesty before he ascended the throne” (Sang Phatthanoi, n.d.: 180). According to the book Royal Biography and Royal Activities of King Taksin of Thonburi (2524: 2), “He led the troops to suppress various factions in order to successfully reunify the Thai kingdom, managing to capture the Burmese camps at Pho Sam Ton and Thonburi in the 12th month of the Pig year, B.E. 2310 … and performed the coronation ceremony to become king on the 3rd day, wan 1, of the month, Year of the Rat, Chula Sakarat 1130 (B.E. 2311).”

“Later, in B.E. 2311, he was formally crowned king with the title ‘Somdet Phra Borom Racha Thi 4,’ but the people commonly called him ‘King Taksin’” (http://www.wangdermpalace.com/kingtaksin/thai_thegreat.html, 30/11/2547).

N. Na Paknam (2536: 49) stated, “Chula Sakarat 1130, Year of the Rat, he ascended the throne as monarch at Thonburi.”

The commemorative book for the opening of King Taksin Monument, Chanthaburi Province (2524: 40), noted, “…Taksin then relocated the people to establish the capital at Thonburi and performed the coronation ceremony as king on Wednesday, 4th wan of the first month, Chula Sakarat 1130, Year of the Rat, which corresponds to 28 December B.E. 2311…”

Natthaporn Bunnak (2545: 32), citing the “Horoscope Chronicle” in Prasum Pongsawadan, Kanchanaphisek Edition, Vol. 1, Bangkok: Fine Arts Department, p. 1, stated: “According to the Royal Chronicles, which correspond with the horoscope chronicle in Prasum Pongsawadan, Part 8, the official ascension to the throne of King Taksin the Great occurred on Wednesday, the 4th wan of the first month, Chula Sakarat 1130, Year of the Rat, corresponding to 28 December B.E. 2311.”

Khajorn Sukpanich (2518: 22–25) wrote in Historical Data of Early Bangkok: “…Regarding the story of King Taksin, it can be established that he led about one thousand troops to break out of the Burmese encirclement from the capital on 3 January B.E. 2309, approximately three months before the fall of Ayutthaya. He captured Chanthaburi on 14 June B.E. 2310, about two months after the fall. He then spent roughly five months gathering people and weapons, and having enough ships built, he led the navy to the river mouth in the 12th month of the Year of the Rat, and the next day captured Thonburi.

As mentioned, we do not have evidence of the exact day he recovered Ayutthaya; we only know it was in the 12th month. When it was agreed to assign a day, the 15th wan of the 12th month, corresponding to 6 November B.E. 2310, was provisionally used.”

… If we try to estimate the time it took for His Majesty to capture the Pho Sam Ton camp and then move to settle in Thonburi, how long would that period be? Would it take several months? Currently, the official date of King Taksin’s coronation is set as 28 December B.E. 2311. That is, King Taksin recaptured Ayutthaya on 6 November B.E. 2310. The fact that the coronation date is set as 28 December B.E. 2311—over 14 months later—sounds unusual. If it were only a month apart, it would seem reasonable, but the reason for such a long delay of 14 months has not been evidenced. It is said that the source for the coronation date comes from the poem praising the king (Khlong Yo Phra Kiat) composed by Nai Suan Mahadlek, though it is still unclear which stanza contains this information. Considering the book by Nai Thongyu Phutphat (Member of Parliament for Thonburi Province, cited in Natthaporn Bunnak, 2545: 3), which was published with calculations converting lunar dates into solar dates by Phraya Barirak Vetchakarn, President of the Astrologers’ Association of Thailand, it can be roughly understood why this date was calculated in such a way. The calculation was based on the date of Ayutthaya’s fall and the date when Chanthaburi was recaptured as the Year of the Pig, and the date of liberation as the Year of the Rat (the person responsible for the lunar date calculation, not the ecclesiastical authority).

Note: From document studies, it was found that the source for Phraya Barirak Vetchakarn’s calculation is cited in one book: Somdet Phra Chao Taksin Maharat by Prayoon Pitsanaka, published in B.E. 2527, page 379.

Since the Year of the Pig corresponds to B.E. 2310, the Year of the Rat must be B.E. 2311. In fact, the events of Ayutthaya’s fall, the capture of Chanthaburi, and the attack on the Pho Sam Ton camp all occurred in the Year of the Rat, during months 5, 7, and 12, respectively. If Chula Sakarat 1130, the Year of the Rat, corresponds to B.E. 2311, then the fall of Ayutthaya, the capture of Chanthaburi, the recapture of Ayutthaya, and the coronation should all be in B.E. 2311 as well. Therefore, the coronation, if it were in the same year, should only be a little over a month after the recapture of Ayutthaya—not 14 months later.

Regarding the coronation ceremony, the Foundation for the Preservation of the Old Royal Palace, Somdet Phra Chao Taksin Maharat (B.E. 2543: 17–18), stated: “…The ceremony was likely conducted in an abbreviated form, but even in its shortened form, it included all the essential elements of the ritual. King Taksin sat on the Phattharabit throne, received the kingship from the Supreme Royal Brahmin according to all the rules of the coronation, and his title and honors were proclaimed in full as Somdet Phra Borom Ratchathiraja of Siam, under the name: ‘Phra Srisanphet Somdet Borom Thammikaratchathiraja Ramathibodi Boromchakrapadsi Baworn Rachabodin Haririnthadathadebodi Srisuviboon Khunruchit Ritthiramesuan Boromthammikaratchadechochai Promthepadeethep Tripuwanathibeth Lokchesadvisut Makutprathetkata Mahaputthangkun Boromnathabopit Phra Phutthachao Yuwah at Krung Thep Maharat Baworn Thawarawadi Si Ayutthaya Mahadilok Nopparat Ratchathaniburirom Udom Phra Ratchaniwet Mahasathan,’ or ‘Somdet Phra Borom Ratcha Thi 4,’ but the people commonly call him ‘Phra Chao Taksin.’ Nevertheless, the government has designated 28 December of every year as the official day of Somdet Phra Chao Taksin Maharat.”