King Taksin the Great

Chapter 6: The Battles of King Taksin the Great with the Burmese Before and After the Fall of Ayutthaya

In 1764, Ayutthaya ordered Phra Ya Tak (Sin) and Phra Ya Phiphat Kosa (Phra Ya Kosa Thibodi) to lead land forces to intercept the Burmese army at Phetchaburi. The Thai forces fought valiantly and successfully drove the Burmese back through the Singkhon Pass to Tanintharyi. The Thai army was able to retain control of Phetchaburi. (Thuan Boonyaniyom, 1970: 35–36)

6.1 When the Burmese forces laid siege to Ayutthaya in 1766, what position did King Taksin the Great hold, and where was his residence at that time?

At that time, King Taksin the Great held the position of Phra Ya Tak, the governor of Tak. King Ekkathat commanded Phra Ya Tak to assist in the defense of Ayutthaya against the Burmese forces. Phra Ya Tak was a skilled and valiant warrior who had distinguished himself in previous battles. As a result, he was promoted to Phra Ya Wachira Prakan, the acting governor of Kamphaeng Phet, succeeding the former governor who had passed away. However, Phra Ya Wachira Prakan (Sin) did not assume his post in Kamphaeng Phet, as he was engaged in defending the capital against the Burmese invaders. (Wina Rojanarata, 1997: 85)

Phra Ya Wachira Prakan (Sin) was later appointed as the commander of the forces sent to resist the Burmese army at Myeik, but he was unable to withstand the enemy’s strength and was forced to retreat to reinforce the defense of Ayutthaya. (Fine Arts Department, Testimonies of the People of the Old Capital: 168) He then took command of the naval forces and established a defensive camp at Wat Pa Kaeo (Wat Yai Chaimongkhon) to prevent the Burmese from advancing into the city. According to the Konbaung-era Burmese Royal Chronicle, the siege of Mang Maha Noratha’s camp was described as follows:

In 1766, the Thai forces within the capital organized a major offensive against the camp of Mang Maha Noratha. The army was divided into two divisions: one commanded by Phra Ya Tan and the other by Phra Ya Wachira Prakan. The forces consisted of 400 war elephants, 1,000 artillery wagons, and 50,000 soldiers. Each elephant was armored in iron up to its chest and mounted with three cannons. On the Burmese side, Mang Maha Noratha assigned five officers to command four units each, amounting to a total of 100 elephants, 500 horses, and 20,000 troops.

The mission took place near Phukhao Thong Chedi.

The battle escalated into close combat. At first, the Thai forces opened fire on the Burmese army with heavy artillery. Then Phra Ya Tan led all 400 war elephants in a fierce charge against the enemy, engaging in combat on elephant-back with the governor of Suphanburi, one of the local rulers who had sworn allegiance to Burma. Before the duel’s outcome could be decided, the governor of Suphanburi was shot and killed by a Thai gunner. Seizing the moment, Phra Ya Tan drove his elephant forward and attacked the Burmese cavalry, breaking their formation. At that moment, the 400 war elephants and all the cannons of the Thai army operated with great effectiveness, causing the Burmese forces to scatter in disorder. The Burmese commander, Mang Maha Noratha, personally led his elephant corps and artillery to counterattack, eventually halting the Thai advance and reversing the situation in favor of the Burmese. Afterward, the Burmese troops spread out and established camps encircling the city from all four directions, though these camps remained at some distance from the city walls. Despite several attempts, the Burmese failed to breach the defenses. (The Burmese chronicle writers often tended to exaggerate the number of Thai troops engaged in battle and understate the Burmese forces, aiming to portray that the Burmese army, though smaller in number, could easily defeat the larger Thai forces. Chanra Prachitromrun, 1993: 116–117)

Sketch map showing the battle positions of Phra Ya Thibet Pariyat, Phra Ya Tan, and Phra Ya Wachira Prakan

(Image from The Fall of Ayutthaya, the Second Time, 1767)

Raids Conducted by Foreign Volunteers and Thai Soldiers (Ayutthaya, 1766) During this period, several groups of foreign volunteers went out to engage in combat with the enemy alongside the Thai forces.

China Four Chinese officials—Luang Choduek, Luang Thong Sue, Luang Naowachot, and Luang Laoya—together with their Chinese volunteer troops, launched an attack on the Burmese camp at Suan Phlu, where they engaged in fierce combat.

Foreigners Krung Phanit, Ritsamdaeng, Wisutsakhon, and Anton, together with many other foreign volunteers, launched an attack on the Burmese camp at Ban Pla Het, engaging in equally fierce fighting.

At that time, a British ship named Alangkapuni was trading in Siam. The crew volunteered to assist in fighting against the Burmese by using the ship’s cannons to fire upon Burmese positions in Thonburi. However, the Burmese retaliated with heavy artillery from the Wichai Prasit Fortress, forcing the British ship to retreat toward Nonthaburi. The British continued to fire their cannons at the Burmese near Wat Khema, but were unable to withstand the counterattack and ultimately fled to the open sea. (Athorn Chanthawimon, 2003: 228)

The bandits, led by Muen Han Kambang, Nai Chan Sue Tia, Nai Mak Si Nhuad, and Nai Jon Yai, together with their followers, also volunteered to fight under the command of Phra Muen Si Saowarak, who served as their commander.

The Atamat volunteers launched attacks on the Burmese camp at Pa Phai, engaging in several fierce battles in which both sides suffered heavy casualties.

The Muslim volunteers included Luang Sriyot, Luang Ratchapimon, Khun Sriworakhan, and Khun Ratchanithan, together with numerous Muslim groups—Malay, Cham, Javanese, and other communities—under the leadership of Phra Chula. They attacked the Burmese camp at Ban Pom. The Burmese forces also had a Muslim commander named Nemo Yokkung Narad, who fought against Phra Chula’s army, and many soldiers from both sides were killed in the confrontation.

The Mon volunteers included Luang Theking, Phra Bamro Phakdi, Phra Ya Kiat, and Phra Ya Ram, together with the Mon people from Sam Khok, Ban Pa Pla, Ban Hua Ro, and other Mon communities who volunteered to join the fight.

The Lao volunteers were led by officials named Saen Kla, Saen Han, Saen Thao, and Wiang Kham, along with many other Lao warriors who offered their service in attacking the Burmese camps.

Afterward, the government appointed Phra Ya Phon Thep to guard the city gates and maintain strict control over the capital. Most of the volunteers mentioned were foreigners, as very few native Thais remained—many had perished in internal conflicts and power struggles, often executed through beheading and extermination of entire families. As a result, the Thai forces during the reign of King Suriyamarin became extremely weakened.

Note:

The Settlements of Foreign Communities in Ayutthaya During the Ayutthaya Period, Phraya Boran Rachathanin once submitted a report to Prince Damrong Rajanubhab during the reign of King Rama V, describing the locations where foreigners had established their settlements in Ayutthaya when it was still the capital.

Sketch map showing the raids conducted by foreign volunteer units and Thai soldiers in 1766

(Image from The Fall of Ayutthaya, the Second Time, 1767)

- 1. The Brahmins resided in front of Wat Nang Muk, Wat Am Mae, and Chikun, where the Hindu shrines and the Giant Swing at the city center were located.

- 2. The Indian and Persian Muslims lived from the western side of the Chinese Gate Bridge to the area behind Wat Nang Muk, extending to Tha Kaya. The locals called this area “Thung Khaek” (the Field of the Foreigners).

- 3. The Cham Muslims settled along the Khu Cham Canal, south of Wat Kaew Fa.

- 4. The Malays lived along the southern part of the Takhian Canal.

- 5. The Makassar people lived on the western bank of the river, south of the mouth of the Takhian Canal.

- 6. The Chinese lived in several areas: behind Wat Chin to Sam Ma Nai Kai and the Chinese Gate, along the Suan Phlu Canal, at the mouth of the Khao San Canal, along the Than Tan Canal, at Ban Din, and on Phra Island.

- 7. The Japanese settled on the eastern bank of the river, south of Ban Suea Kham and north of Ko Rian.

- 8. The Mon people lived at Ban Pho Sam Ton and at the northern mouth of the Takhian Canal.

- 9. The Lao Phung Dam (Black-Bellied Lao) lived in Uthai District and on the eastern side of Bang Pa-in District.

- 10. The Lao Phung Khao (White-Bellied Lao) lived along the Mahaphram River, outside the Khunon Pak Khu area.

- 11. The Shan (Tai Yai) settled at Ban Pom, north of the Royal Elephant Kraal.

- 12. The Vietnamese lived north of Wat Nang Krai, extending to the northern mouth of the Takhian Canal.

- 13. The Tanintharyi people lived at Khunon Luang and Wat Prot Sat.

- 14. The Khmer settled along the Nakhon Chaisi River, south of Ngio Rai, near Wat Khang Khao.

- 15. The Portuguese lived on the western bank of the river, behind Ban Din.

- 16. The Dutch in Ayutthaya lived on the eastern bank of the river, south of Wat Phanan Choeng. They also had a warehouse at the mouth of the Bang Pla Kod Canal on the Chao Phraya River near Phra Pradaeng, a place known as “New Amsterdam.”

- 17. The English lived on the eastern bank of the river, south of the Dutch settlement, extending northward to the mouth of the Mae Bia River.

- 18. The French settled at Ban Pla Het, near the northern mouth of the Takhian Canal. (Athorn Chanthawimon, 2003: 223)

6.2 What were the causes that made King Taksin the Great lose heart?

During the defense of the capital, although Phra Ya Wachira Prakan (Sin) commanded the battles and fought the enemy with great skill, he encountered several circumstances that deeply disheartened him, including the following:

1) In 1766, Phra Ya Wachira Prakan led his troops to attack and successfully capture the Burmese camp at Wat Prot Sat. However, the commanding officers responsible for the defense of the capital failed to send reinforcements. Mang Maha Noratha then dispatched additional forces, enabling the Burmese to reclaim the camp. Consequently, Phra Ya Wachira Prakan was forced to abandon the position and retreat, causing the Thai army to scatter back into the city. He was later accused of wrongdoing for the army’s defeat. (Praphat Trinarong, 1999: 14)

2) In the twelfth lunar month, when the plains were flooded, it was reported in the capital that the Burmese were advancing by river across the flooded fields, seemingly to prepare for the siege of Ayutthaya from the east. King Ekkathat therefore appointed Phra Ya Phetchaburi as the naval commander and Phra Ya Wachira Prakan (Sin) as the rear guard to intercept the Burmese forces. They established their positions at Wat Pa Kaeo (Wat Yai Chaimongkhon) to block the approaching Burmese army. When the Burmese troops arrived in great numbers, Phra Ya Phetchaburi intended to lead a naval attack. However, Phra Ya Wachira Prakan (Sin), seeing that the enemy’s strength was overwhelming, advised him to wait and observe the Burmese movements first. Phra Ya Phetchaburi disregarded this advice and pressed forward with his fleet to engage the Burmese near Wat Sangkhawat. The Burmese, having superior numbers, surrounded his flotilla and hurled black powder jars into the ships, causing massive explosions that destroyed them. Phra Ya Phetchaburi was killed in battle, and his remaining troops either died or fled in disorder. Phra Ya Wachira Prakan (Sin)’s force did not engage the Burmese but withdrew to establish a defensive camp at Wat Phichai, which had been Phra Ya Phetchaburi’s former base (now located below the present-day railway station). From that time on, Phra Ya Wachira Prakan (Sin) did not return to the capital. Nevertheless, he was accused of negligence in battle and of abandoning Phra Ya Phetchaburi on the battlefield, which caused him great distress. (Thuan Boonyaniyom, 1970: 39–40)

3) Three months before the fall of Ayutthaya, the city faced a severe shortage of gunpowder. An order was therefore issued requiring any unit wishing to fire its cannons to first seek permission from the Sala Luk Khun (the royal council hall), since the royal consorts (Mom Pheng and Mom Man) and the palace attendants were easily frightened by the sound of gunfire. (Wisetchaisri, 1998: 304) One day, when the Burmese advanced from the east—where Phra Ya Wachira Prakan was stationed—he found the situation critical and ordered his troops to open fire with cannons without first seeking permission from the Sala Luk Khun. As a result, he was reported and brought to trial, though he was given only a reprimand in consideration of his previous distinguished service. (Praphat Trinarong, “The Era of King Taksin the Great,” Thai Journal 20(12), October–December 1999: 14)

(Image from The Fall of Ayutthaya, the Second Time, 1767)

6.3 Why did King Taksin the Great decide to break through the Burmese siege and escape from Ayutthaya?

The Burmese army besieged Ayutthaya for about two years. Phra Ya Wachira Prakan foresaw that the capital would inevitably fall, as the Burmese reinforcements were overwhelmingly strong while Ayutthaya’s defenses had grown weak. The city’s weaponry and military supplies were depleted and unfit for battle, and the king showed little determination to address the crisis, allowing events to unfold as they might. The people’s morale collapsed, and chaos spread throughout the city. (Thuan Boonyaniyom, 1970: 40) Moreover, Phra Ya Wachira Prakan’s forces were suffering from severe shortages of provisions. Continuing the fight would only mean sending his soldiers to die in vain. He therefore devised a plan to break through the Burmese siege in order to gather food supplies, manpower, and weapons, with the intention of returning later to liberate Ayutthaya. He reasoned that it was better to withdraw and fight again with purpose than to remain and perish without reason. (Ceremony for the Unveiling of King Taksin the Great Monument, Chanthaburi Province, 1999: 20; http://www.wangdermpalace.com/kingtaksin/thai_millitaryact.html, accessed 22/11/2002)

6.4 When did King Taksin the Great lead his troops to break through the siege and escape from Ayutthaya?

Phra Ya Wachiraprakan (Sin) decided to gather together a group of loyal followers, both Thai and Chinese, numbering 500 men (according to the Royal Chronicle of Thonburi, Phanchanthanumat version (Choem), it was recorded that there were approximately over 1,000 Thai and Chinese soldiers). The military officers who shared his resolve included Phra Chiang Ngoen, Luang Phrommasena, Luang Phichairacha, Luang Ratchasena, Khun Aphai Phakdi, and Muen Ratchasenha (Thuan Boonyaniyom, 1970: 40). They departed from the camp at Wat Phichai on Saturday, the 6th day of the waxing moon in the second lunar month, the Year of the Dog, A.D. 1128, at dusk, corresponding to January 4, 1767 (three months before the fall of Ayutthaya). They broke through the Burmese encirclement to the east (or southeast, according to Praphat Trinarong, 1981: 14), heading toward Ban Hantra and Ban Khao Mao, as the Burmese forces had not yet surrounded the area closely, with only distant encampments and a small number of troops stationed there (http://www.wangdermpalace.com/kingtaksin/thai_millitaryact.html, accessed November 22, 2002; and Royal Chronicle of Ayutthaya, p. 69).

Phraya Tak gathers his followers and escapes from Ayutthaya

(Photo courtesy of Muang Boran)

Pharadee Mahakhan (1983: 17–18) expressed her opinion regarding King Taksin the Great’s departure from Ayutthaya three months before its fall as follows:

“The fact that King Taksin of Thonburi fled from Ayutthaya, when considered under Article 40 of the Law on Treason and Warfare, would render him guilty of treason and subject to the death penalty. However, since His Majesty successfully escaped and Ayutthaya fell to the Burmese three months later, the charge of treason was thereby nullified. Moreover, some scholars have observed that King Taksin’s departure from Ayutthaya, along with his followers, was not an act of fleeing for personal safety but rather a strategic retreat to gather forces in order to reclaim Ayutthaya and to restore and uphold Buddhism to flourish once again. This is supported by the Royal Chronicle, Royal Autograph Edition, which records that when His Majesty reached Hin Khong and Nam Kao in the Rayong region…”

The King consulted with his generals and soldiers, saying, “Ayutthaya will surely fall to the Burmese. I shall gather the people from all the eastern provinces in great numbers and then lead them back to reclaim the capital as our royal city once more. I will protect and care for the monks, Brahmins, and the common people who have become destitute and homeless, so that they may live in peace and happiness. I shall also restore and elevate the Buddhist religion to flourish as it once did. I will establish myself as ruler so that all people will respect and revere me greatly, for only then will the task of restoring the kingdom be accomplished with ease…” (Royal Chronicles of Ayutthaya, Royal Autograph Edition of King Mongkut, pp. 603–604)

6.5 After breaking through the Burmese forces, where did King Taksin the Great lead his army next?

When Phraya Wachiraprakan (Sin) (later King Taksin the Great) and his followers left the camp at Wat Phichai, they encountered Burmese forces stationed to the east of the temple. Through swift and fierce combat, which was characteristic of his infantry and cavalry troops, they successfully broke through the Burmese lines and advanced eastward.

Pharadee Mahakhan (1983: 18–19) proposed reasons why King Taksin the Great decided to move eastward to gather troops along the eastern coast as follows:

- 1. The eastern coastal towns still had sufficient manpower, weapons, and provisions to be reorganized into a fighting force capable of reclaiming Ayutthaya.

- 2. This region was not part of the route taken by the Burmese army; therefore, it had not suffered destruction, and the Burmese were unfamiliar with the terrain.

- 3. While Ayutthaya was under siege, Chinese merchants had shifted their trade activities to the eastern coastal areas, particularly around Chanthaburi and Trat. Once these merchants acknowledged King Taksin’s authority, he would receive financial support, as well as gain convenient access to weapons and additional food supplies.

- 4. The eastern coastal towns were not far from Ayutthaya and could be reached by waterways. King Taksin likely anticipated that if he were to lead his army back to reclaim the capital undetected by the Burmese, the waterways would offer an easy route. Moreover, if his forces were defeated, he could retreat into Cambodian territory for safety.

The Burmese did not cease their pursuit of Phraya Wachiraprakan (Sin)’s forces. Fighting continued as his troops retreated, engaging the enemy while withdrawing until late at night when the battle finally subsided. At that time, a great fire broke out in Ayutthaya, and the flames illuminated the sky from afar. Phraya Wachiraprakan (Sin) reached Ban Pho Sao Han (also known as Pho Sang Han, though the Phra Ratchaphongsawadan Krung Thonburi, Chantanumas version, refers to it as Pho Samhao or Pho Sanghan) late at night. Early the next morning, he saw Burmese soldiers approaching the village, so he quickly organized his forces to engage them in battle on the plain between the temple and the village. The villagers united and fought alongside Phraya Wachiraprakan with great determination, ultimately defeating the Burmese and killing many of them, while the remaining enemy troops retreated.

Note: According to oral accounts passed down through generations, Mrs. Jirawan Kongsomswang, the headteacher of Ban Pho Sao Han School, recounted that among the villagers’ forces was a brave woman named “Nang Pho,” who fought valiantly at the front lines without fear of Burmese spears or swords until she was killed in battle. After the victory, King Taksin the Great named the village “Ban Pho Sao Han” (“Village of the Brave Woman Pho”) in her honor. Today, the villagers have built a statue of Nang Pho as a memorial for future generations to remember her bravery, located in Village No. 3, Ban Pho Sao Han, Pho Sao Han Subdistrict, Uthai District, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya Province.

Phraya Tak and his followers escaped safely from Ayutthaya and could see the flames engulfing the city from afar.

(Photo from the book Pradap Ko Luead Duead)

Statue of Nang Pho, Ban Pho Sao Han

(Photo from the book War: History)

After achieving victory, Phraya Wachiraprakan led his forces from Ban Pho Sao Han toward Ban Phrannok, a distance of about three kilometers. There, they rested and reorganized their troops. While some Thai soldiers went to nearby villages in search of provisions, a Burmese detachment from Bang Khang (the site of the old fort of Prachin Buri) was en route to Ayutthaya, consisting of 30 cavalrymen and about 200 infantrymen. When the Burmese encountered the Thai soldiers gathering supplies, they surrounded and pursued them. Some of the Thai troops escaped to Ban Phrannok and reported the situation to Phraya Wachiraprakan. With his quick and strategic acumen, he ordered his men to form a winged formation to encircle the Burmese on both flanks. Mounted on horseback with five loyal soldiers, he advanced to confront the 30 Burmese horsemen who were moving carelessly forward. Taken by surprise, the Burmese cavalry were immediately attacked by Phraya Wachiraprakan’s force. Panic ensued, and the Burmese fought while retreating until they collided with their 200 infantrymen following behind. At that moment, the Thai infantry who had surrounded them on both sides launched an assault, advancing swiftly and striking down the Burmese soldiers. The remaining enemy troops were either killed or fled in complete disarray.

Note: Ban Phrannok was home to an old hunter named Thao Kham, who lived alone and made his living hunting birds. The area was abundant with birds, so Thao Kham often went out hunting with his crossbow, and it is said that he shared the birds he caught with the soldiers of Phraya Wachiraprakan, who roasted or cooked them during that time. In the old days, people in rural areas were named according to their trades—those who hunted jungle fowl were called “Phraen Kai,” and those who hunted rabbits were called “Phraen Kratai.” Since Thao Kham hunted birds, he became known as “Phraen Nok,” and the village took its name from him. A statue of Thao Kham was also made in his memory. At Ban Phrannok, Phraya Wachiraprakan displayed great valor, leading five Thai cavalrymen to fight against thirty Burmese horsemen, supported by infantry on both sides in nearly equal numbers. In the end, the Burmese were defeated and fled in disorder. This event took place at Ban Phrannok on January 4, 1766. In commemoration of this victory, Thai cavalry units later designated January 4 of every year as “Cavalry Day,” and a memorial monument was erected at Ban Phrannok, Village No. 2, Pho Sao Han Subdistrict, Uthai District, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya Province, on January 4, 1991. Because of the village’s historical significance, the government named a neighborhood on the Thonburi side “Ban Phrannok,” near Ban Chang Lo and Ban Khmin. After this victory, Phraya Wachiraprakan gained the support of local villagers who had been hiding from the Burmese and sent word for more to join his forces, including village leaders known as “Nai Song.”

Statue of Thao Kham at Ban Phran Nok (Image from the book War: History)

Khun Muen Phanthanai of Ban Bang Dong did not believe the persuasion of Phraya Wachiraprakan and therefore refused to join his cause. Consequently, Phraya Wachiraprakan subdued him by force and brought the area under his control before marching onward to Na Roeng (present-day Ban Na District) in Nakhon Nayok Province. There, he acquired additional troops, elephants, horses, transport animals, and provisions. The army then advanced through Nakhon Nayok toward the area of Kobchae checkpoint (now located in Prachantakham District, where the Prachantakham River flows into the Prachin Buri River). From the area near the Kobchae checkpoint, they crossed to the eastern bank. Phra Khru Srimaha Phot Khanarak, the abbot of Wat Mai Krong Thong, related that on the eastern side, where King Taksin’s troops had crossed, there now stands the ruins of an old temple named Wat Kachae, though the date of its construction is unknown. It must have been built after the King’s forces had passed through the area.

After crossing to the eastern bank, Phraya Wachiraprakan ordered the supply unit and carriers to move across the plains toward Ban Mao Ram, Phai Khat, and Ban Khu Lam Phan, which lay along the edge of Thung Srimaha Phot. His main force followed as the last group. While moving through Ban Khu Lam Phan, Burmese troops from Pak Nam Chao Lo (believed to be Pak Nam Yothaka), located south of Prachin Buri, pursued them by both land and water routes. Hearing the sound of Burmese gongs, drums, and seeing their battle flags approaching, Phraya Wachiraprakan quickly ordered the supply unit to move to safety and promptly arranged his forces. He directed his troops to establish ambush lines and designated final firing positions for attack. He chose the thickets of reeds as both cover and movement routes. Simultaneously, about one hundred Thai soldiers were sent into the open field to engage the Burmese and then feign retreat toward the prearranged firing line. When the Burmese, believing the Thais to be in retreat, pursued them to within range, the ambushed troops opened fire simultaneously, inflicting heavy casualties. Several subsequent Burmese reinforcements also fell under the gunfire and retreated in disarray. Phraya Wachiraprakan led his ambushing troops in pursuit, killing many Burmese amid the thickets, leaving their corpses scattered, while the survivors fled in panic. After that, the Burmese forces ceased their pursuit entirely.

Following the victory over the Burmese at Ban Khu Lam Phan in Prachin Buri, Phraya Wachiraprakan reorganized his army and moved approximately six kilometers southward to make camp near Wat Ton Pho, in Khok Pip Subdistrict, Khok Pip District, Prachin Buri Province. On Monday, the 14th waxing day of the second lunar month, the Year of the Dog, 1766, his forces departed from Wat Ton Pho in Si Maha Phot, marching through the areas of Chachoengsao (then called Mueang Paet Riu) and Chon Buri (then called Mueang Bang Pla Soi), and reached Ban Na Kluea. At Ban Na Kluea, a man named Nai Klam led his men to obstruct the Thai army. Phraya Wachiraprakan ordered cannon fire into the group, whereupon Nai Klam immediately submitted. From Ban Na Kluea, the forces continued through Pattaya, Na Chom Thian, Kai Tia, and Sattahip. From Sattahip, they proceeded along the coastal villages, passing Ban Hin Dong and Ban Nam Kao, and finally established a fortified camp near Wat Lum (Wat Lum Mahachai Chumphol or Wat Maha Chai Chumphuphon) in Ban Tha Du, not far from the old camp of Mueang Rayong (Chusiri Chamraman, 1984: 89).

Note:

Phraya Tak (Phraya Wachira Prakan) led his forces to establish a camp at Wat Lum, in front of Rayong City (presently known as Wat Lum Mahachai Chumphonphu Phon), and laid siege to the city of Rayong. Later, the people of Rayong built the Shrine of King Taksin the Great in front of Wat Lum Mahachai Chumphonphu Phon, where it remains a revered site to this day. Next to the shrine stands a large sathue tree, known as the “King Taksin Sathue Tree,” believed to be the very tree under which King Taksin once rested, using its shade as shelter from the sun and wind while establishing his military camp.

Phraya Taksin advanced his forces with the intention of attacking Rayong. At that time, it was customary to use Buddhist monks as intermediaries or envoys to negotiate disputes.

(Image courtesy of Muang Boran)

It is a tree that should be preserved as a memorial, similar to the American Elm under which President George Washington once rested during the Revolutionary War. Americans have carefully maintained it to this day, in remembrance of Washington’s contributions and the tree’s role in providing shelter that helped achieve victory and secure the nation (Samanwanakit, Luang, 1953: 18).

In Rayong, the city’s ruler at the time, named Bun or Bun Rueang, served as the governor of Rayong (Chusiri Jamraman, 1984: 69) and agreed to cooperate with Phraya Wachira Prakan. Another group, composed of officials from the old city administration including Luang Phon Saen Han, Khun Cha Mueang, Khun Ram, and Muen Song, held the view that Phraya Wachira Prakan audaciously gathered troops and invaded the city, committing an offense against the kingdom, and therefore refused to join his efforts.

Later, the governor of Rayong hesitated but eventually joined Khun Ram and Phra Muang Song under Phraya Wachira Prakan. After resting for two days, on the night of the second day, Khun Ram and Phra Muang Song, leading the Rayong forces, prepared to attack from the old city camp. Phraya Wachira Prakan learned of their plan to strike at night and secretly made preparations. The governor of Rayong remained in the camp under Phraya Wachira Prakan’s control. When the city forces moved from the old camp to encircle Phraya Wachira Prakan’s camp, he ordered war cries and gunfire, extinguished all fires throughout the camp, and confronted Khun Cha Mueang Duang.

Phraya Wachira Prakan (Sin) brought a force of 30 men from Rayong city via Wat Noen, located north of his camp, intending to break into the camp. As they crossed a bridge about 10 meters from the camp, Phraya Wachira Prakan’s soldiers fired their guns, causing Khun Cha Mueang and his men to fall from the bridge. Those following behind were startled and fled. Taking advantage of the situation, Phraya Wachira Prakan ordered his soldiers to shout war cries and charge, forcing the Rayong city forces to retreat into the old camp. The soldiers pursued them to the old camp, killed many inside, scattered the survivors, and burned the camp. That night, Rayong city came under the control of Phraya Wachira Prakan, while Ayutthaya had not yet fallen to the Burmese. The fact that Phraya Wachira Prakan (Sin) captured Rayong city in this manner could be seen as a violation of the law. Therefore, he was careful not to establish himself as a rebel and was formally referred to in orders as “Phraya Prasat,” the chief city official. His followers, however, began calling him “Chao Tak” from that time onward (Veena Rojanarat, 1997: 88).

During the period when Chao Taksin held authority in Rayong, Ayutthaya had not yet fallen. He established communication and cooperation with other cities, such as Chanthaburi, Chonburi, and Banthaimat, which promised to join forces against the Burmese. After the fall of Ayutthaya, the city rulers hesitated and considered asserting independence. Chao Taksin therefore prepared to subdue them, aiming to unite them under a single command for coordinated operations to drive the Burmese from the land. His first action was to suppress Khun Ram, Muen Song, at Klaeng. After achieving victory, he moved his forces to Chonburi to persuade Nai Thongyu Noklek to join him and appointed him as Phraya Anurathaburi or Phraya Anurathaburi Sri Mahasamut.

Note: Phraya Anurathaburi Sri Mahasamut, the governor of Chonburi, was originally named Nai Thongyu Noklek. When King Taksin arrived in Rayong, he learned that Nai Thongyu Noklek, in collusion with the local administration of Rayong, was gathering forces to act against him. He therefore planned an ambush, scattering their troops. Nai Thongyu Noklek fled to Chonburi but later surrendered and pledged loyalty, after which he was appointed Phraya Anurathaburi Sri Mahasamut to govern Chonburi.

Subsequently it became known that Phraya Anurathaburi had behaved improperly, turning to piracy and plundering merchant junks. When King Taksin learned of this while advancing his forces toward the mouth of the Chao Phraya, he halted and conducted an inquiry in Chonburi; the investigation established Phraya Anurathaburi’s guilt and he was executed. As for Nai Thongyu Noklek, it was said that he possessed an amulet of invulnerability — wounds could not be inflicted upon him because his navel was made of copper — so he was bound, weighted and drowned at sea.

The next major campaign was the attack on Chanthaburi (formerly called Chanthaburi), a long-established and strongly walled eastern city. When Chao Tak’s request for cooperation was rebuffed and, on the contrary, Phraya Chanthaburi plotted to lure him in order to destroy him, the assault on Chanthaburi became unavoidable. The Thai account of the war against Burma describes the events as follows.

Phraya Chanthaburi, fearing that Chao Tak would not reconcile and might one day attempt to seize Chanthaburi, conferred with Khun Ram and Muen Song and concluded that open battle against Chao Tak would be difficult because Chao Tak was a skilled and experienced commander. They resolved instead to use subterfuge to entice Chao Tak into the city and thus make it easy to eliminate him. Acting on this plan, Phraya Chanthaburi invited four monks to serve as envoys to summon Chao Tak to Chanthaburi. The monk envoys arrived in Rayong.

At that time Chao Tak was in Chonburi; when the envoys awaited his return and then reported that Phraya Chanthaburi, angered by the enemy’s ravaging of Ayutthaya, was sincerely willing to assist Chao Tak in restoring the realm, and that Chanthaburi was abundant in provisions and therefore suitable as a base for assembling a large army to reclaim Ayutthaya, Chao Tak accepted their words and allowed his troops to rest and recover. He then permitted the monk envoys to guide his forces toward Chanthaburi.

When Chao Tak reached Bang Kracha Hua Waen, some 200 sen from Chanthaburi, Phraya Chanthaburi sent a royal official to receive him and stated that quarters had been prepared on the riverbank opposite the city to accommodate the army; the official was to lead the troops to those lodgings. Chao Tak ordered his forces to follow the official, but before they reached Chanthaburi someone warned him that Phraya Chanthaburi, in league with Khun Ram and Muen Song, had secretly mobilized troops within the city and intended to strike Chao Tak’s army while it was crossing the southern river.

Chao Tak quickly acted to prevent his army from following the royal official across the river and instead ordered the formation to turn north, proceeding directly to establish a position at Wat Kaew, about five sen from the Tha Chang gate of Chanthaburi. Phraya Chanthaburi, seeing that Chao Tak did not cross the river as intended and instead stationed his troops along the city perimeter, was alarmed. He hurriedly had his soldiers take positions along the ramparts and sent Khun Phromthiban, the river-side officer, along with other notable men, to approach Chao Tak to request a meeting with Phraya Chanthaburi inside the city. Chao Tak, however, instructed Khun Phromthiban to return and tell Phraya Chanthaburi that originally, Phraya Chanthaburi had sent monks as envoys to invite him to discuss plans for reclaiming Ayutthaya, and he had understood this as a sincere invitation and came accordingly. Being a ruler of Kamphaeng Phet with the rank of ten-thousand sakdi and holding a higher status than Phraya Chanthaburi, he expected a proper reception. Yet upon arrival, Phraya Chanthaburi did not come out to welcome him; instead, he mobilized his forces along the ramparts and colluded with Khun Ram and Muen Song, who had twice previously caused him harm, treating him as an enemy. Chao Tak declared that if Phraya Chanthaburi wished him to enter the city, he must either come out personally or send Khun Ram and Muen Song to swear an oath of trust. Only then would he recognize Phraya Chanthaburi’s sincerity and continue to regard him with fraternal respect.

Khun Phromthiban returned to deliver this message to Phraya Chanthaburi, but he did not come out, nor did he send Khun Ram and Muen Song. Instead, they merely sent a meal offering and reported that Khun Ram and Muen Song were too afraid to appear. Phraya Chanthaburi seemed unsure how to compel their appearance. Chao Tak, displeased, instructed that the message be returned with a warning: since Phraya Chanthaburi had shown no goodwill, he should simply safeguard his city carefully. Seeing that his forces outnumbered Chao Tak’s, Phraya Chanthaburi closed the city gates and fortified the defenses, preparing to hold the city firmly.

Chao Tak’s army prepared to launch an attack on Chanthaburi (image courtesy of Muang Boran).

A portion of Chao Tak’s army, filled with the soldiers’ fervor and determination (image courtesy of Muang Boran).

He ordered his commanders and soldiers to cook their meals together and then to dispose of any leftovers completely; that night they were to press the attack on Chanthaburi without delay, enter the city and take their morning meal there, and if the city could not be taken, they were to die together at once.

At that moment Chao Tak found himself in a precarious situation, having taken up position on the outskirts while the enemy, superior in numbers, held the city; the enemy was fearful of his prowess and dared not sally forth, but if Chao Tak were to withdraw they could encircle and attack him from several directions because this was enemy territory. Remaining in place would mean a lack of provisions, as if awaiting the enemy to choose the time to strike at will. As a warrior he perceived at once that he must seize the initiative, lest he be put to shame, so he summoned his commanders and ordered, “Tonight we shall attack Chanthaburi. After the evening meal is cooked and eaten, every man must pour away any remaining food and break the cooking pots; tomorrow morning we will take our breakfast inside the city. If we do not capture the city tonight, we shall all die together.” The commanders, having long witnessed Chao Tak’s authority, dared not disobey and complied.

Phraya Tak’s army advanced to attack Chanthaburi, observing the houses,

the people, and the forces approaching the city (image courtesy of Muang Boran)

Phraya Tak’s army advanced to attack Chanthaburi

(image courtesy of Muang Boran)

As night fell, Chao Tak assigned the Thai and Chinese soldiers to infiltrate the city without alerting the townspeople, instructing them to listen for the signal gun to attack simultaneously, but not to make any loud noises. Once any group had entered the city, they were to raise a shout as a signal for the others. When preparations were complete, at the auspicious hour of 3 a.m., Chao Tak mounted his elephant, Phang Khiri Banchorn (or Phang Khiri Kunchorn Chatthan), and fired the signal gun to command all soldiers to attack simultaneously. Chao Tak himself drove the royal elephant to break through the city gate, while the townspeople on guard fired a large number of cannons and firearms.

The mahout of the royal elephant saw that the city’s cannons were numerous and feared they might hit Chao Tak, so he pulled the royal elephant back. Chao Tak, displeased, drew his sword to strike, and the mahout, terrified, pleaded for his life, then guided the elephant back to break down the city gates. The troops rushed into the city, and the townspeople, realizing the enemy had entered, abandoned their posts and fled. Phraya Chanthaburi took his family and fled by boat to Banteay Meas. When Chao Tak captured the city of Chanthaburi, it was Sunday, the 7th month, Year of the Pig, B.E. 2310 (June 14, 1767), two months after the fall of Ayutthaya.

The book Sampao Siam: The Legend of the Chinese of Bangkok states: “…During the assault on Chanthaburi, King Taksin received assistance from Chinese Jian, a ship captain from Trat, who was later appointed Phraya Aphai Phiphit, governor of Trat…” (Phimprapai Pisankul, 1971: 97).

After capturing Chanthaburi, Chao Tak persuaded the people to return to their homes, showing mercy and making it clear that he held no grudge against those who had formerly opposed him. Once the city was restored to order, he led his army down to Trat, marching for seven days and seven nights. The officials and townspeople, intimidated, submitted willingly. At that time, several Chinese junks were anchored at the mouth of Trat. Chao Tak summoned the ship captains to present themselves. The Chinese resisted and fired upon the royal officials. Upon learning this, Chao Tak boarded his warship to surround the junks and ordered the Chinese to submit. They refused and continued firing their cannons. After half a day of fighting, Chao Tak captured all the Chinese junks along with a large amount of property and military supplies. Having secured Trat, Chao Tak returned to establish his camp in Chanthaburi (Ruamsak Chaikomintorn, Phraya, Phaensuk San, 2000: 18–26).

The royal chronicles record: “…Phraya Chanthaburi took his children and wife and fled the city, sailing to Banteay Meas. Thai and Chinese troops pursued and captured his family, seizing a large amount of property, gold, silver, cannons, small firearms, and various weapons. Chao Tak then established control over the city of Chanthaburi…” (Image courtesy of Muang Boran)

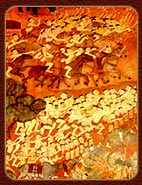

The route taken by King Taksin and the locations of battles

(Image courtesy of War: History)

The escape route of Phraya Chiraraprakarn (Sin) from Ayutthaya can be summarized as follows:

Wat Phichai Camp – Ban Pho Sawahan – Ban Pran Nok – Nakhon Nayok – Prachinburi – Chonburi – Rayong – Chanthaburi – Trat – Chanthaburi.

6.6 Why did King Taksin choose Chanthaburi as the city to regroup and recover his forces after breaking through the Burmese, before Ayutthaya fell? Why did he not choose to go to other cities?

- 1. Heading east had several strategic reasons. After breaking through the Burmese, returning to the city of Tak was impossible, as many areas were under Burmese control, and even Tak itself was occupied by them.

- 2. King Chulalongkorn hypothesized that King Taksin chose Chanthaburi because moving east from Chonburi would place him beyond the reach of the Burmese, who would not follow to engage in battle.

- 3. Chanthaburi was an eastern coastal city, serving as a hub for communication and connections with other regions, including southern Thailand, Cambodia, and Phutthaisong.

- 4. The city’s location made it a convenient point for retreat or further movement if necessary.

An important point that historians often overlook is that Chanthaburi was a city where King Taksin of Thonburi had previously traveled for trade while serving as a caravan leader in Tak. The route from Tak–Ayutthaya–Chonburi–Rayong–Chanthaburi was a path he was familiar with and skilled in navigating.

Most importantly, Chanthaburi had a dense community of Teochew Chinese settlers who were well-acquainted with Phraya Taksin, as they shared the same Chinese ancestry. Traveling to Chanthaburi was, therefore, like returning to a territory he knew well and felt safe among people he trusted and was familiar with.

All of these reasons explain why he chose Chanthaburi as the city to rest, regroup, and gather his army (Nithi Eawsriwong, 1986: 69; Chanthaburi City Principles and History, 1993: 61).