King Taksin the Great

Chapter 4: The Wars Between Thailand and Burma (The 24th War, 1765–1767)

4.1 What Were the Characteristics of the Burmese Army in This Campaign?

Some have argued that King Chulalongkorn was the first to describe the Burmese army that invaded on this occasion as having “come like guerrillas,” meaning they lacked the strength to conduct a decisive siege of the capital and instead roamed and plundered the surrounding areas for three years before finally taking Ayutthaya. Somdet Krom Phraya Damrong Rajanubhab wrote that the Burmese force was a bandit army rather than a royal army, lacking even a clear objective to attack Ayutthaya, since their original aim had been merely to subdue Tavoy; finding the Siamese weak, they advanced into the suburbs of the capital. He did not accept the assertion in the Burmese chronicles that the Burmese planned simultaneous advances from the north and the south toward Ayutthaya, considering such an idea a later invention of the Burmese chronicles. (ไทยรบพม่า , 2507 : 311-314)

Sunet Chutintharanon (2000: 79–83) commented that, until now, understanding of the war that led to the fall of Ayutthaya in 1767 within Thai scholarship has been constrained by the notion that the Burmese army “came like guerrillas”—that is, the force was not a conventional royal army, its recruited levies were few in number, it lacked advance planning, and it only pressed forward when it found Ayutthaya weak. Furthermore, the forces that advanced from the north and the south acted with a degree of independence from one another.

In contrast, the Ho Kaew and Konbaung chronicles state that King Mangra had orderly, prearranged preparations to attack Ayutthaya. King Mangra even reasoned that the Ayutthaya kingdom had never before been utterly destroyed, so relying solely on the army of Neimyo Thihapate, which advanced via the Chiang Mai route, would make success difficult; it was therefore necessary to dispatch Mahanoratha to assist operations on the other side.

The sequence of operations in this war can be divided into four stages:

1. Guerrilla plundering of various towns;

2. Assaults on frontier towns and the advance to the suburbs of the capital;

3. Operations during the rainy season and seasonal floods;

4. The fall of the capital. (Chanya Prachitromran, 1993: 56)

Moreover, both Burmese chronicles explicitly state that the armies advancing by the Chiang Mai and Tavoy routes were large forces personally commanded by their generals from the outset, and were not split into guerrilla detachments operating in advance. The Burmese forces exploited their superiority to sweep through key towns along both the northern and southern lines of advance without exception, including Phitsanulok — a city that many Thai historians have believed did not fall to the Burmese. The chronicles report that the army of Neimyo Thihapate, which moved along the Chiang Mai route, not only attacked Phitsanulok but also established a major headquarters there to plan subsequent operations against the lower Chao Phraya basin.

Crucially, Burmese evidence, both direct and indirect, indicates that although Neimyo Thihapate’s and Mahanoratha’s forces operated on different axes, their actions were coordinated and mutually supportive, progressing in stages to encircle Ayutthaya by destroying or occupying surrounding towns so that no relief could reach the capital.

Phu Khao Thong Stupa is an important great stupa located outside Ayutthaya, approximately 2 kilometers to the northwest of the city. It stands 90 meters tall (2 sen, 5 wa, 1 khuep) and is situated on a mound, with the surrounding area often flooded. The site is historically significant as a strategic battlefield between Ayutthaya and the Burmese army during both sackings of the capital. After the second fall of the city, the temple became abandoned, yet the great stupa remained an important Buddhist site, attracting pilgrims, as noted in Sunthorn Phu’s Nirat Phu Khao Thong. The current structure of the stupa was restored during the administration of Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram in 1956. (Image from the book Ayutthaya and Burengnong Ka Yodinratha)

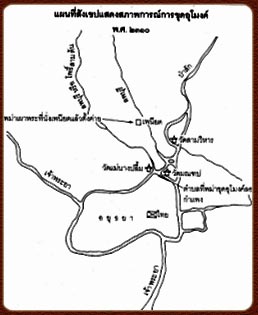

Burmese sources also indicate that Mahanoratha’s army, which reached the suburbs of the capital before Neimyo Thihapate’s forces, did not recklessly advance to encircle the city independently. Instead, they held their position at the village of Kanni, north of Thigok, waiting until they learned that Neimyo Thihapate’s army had reached the outskirts of the capital. Only then did they advance from Kanni and take position behind Phu Khao Thong Stupa (which the Burmese chronicles refer to as the stupa built by King Hongsawadi Changkaew).

Note:

Burmese sources also indicate that Mahanoratha’s camp at Thigok, which was established before Neimyo Thihapate’s army reached the suburbs, was not an impulsive encirclement carried out independently. Instead, the camp was strategically located, and Neimyo Thihapate’s advance prompted coordinated action. According to Na Paknam, Mahanoratha’s camp at Thigok was exceptionally large, comparable to an entire town: “Because the river in this area curves like a horseshoe, at the junction of the Chao Phraya and Noi Rivers, the Burmese established their camp at Wat Thigok and built walls across the tips of the horseshoe to both riverbanks. The walls were constructed of solid brick (though most bricks have since been removed by locals). The Thigok camp was historically famous, with extensive grounds covering several dozen rai, including elephant and horse mounds, resembling a small city.” This evidence demonstrates that the Burmese did not invade like unplanned guerrillas; their selection of strategic positions and the remaining fortifications indicate preparation for a long-term campaign and effective planning to address seasonal floods, aiming from the outset to capture Ayutthaya as the primary objective. (Wiset Chaisri, 1998: 202)

More importantly, both the Ho Kaew and Konbaung chronicles depict that the rulers of Ayutthaya prepared thoroughly and fought vigorously during the later fall of the capital, contrary to the perception of weakness.

The Burmese chronicles describe the military strategy that the Ayutthaya king intended to employ, conveyed through a conversation between Phaya Kuratit and King Ekatat (referred to in the Burmese chronicles as Ekathat Racha in Thai translation). Phaya Kuratit reported that the invading Burmese armies from both routes not only had vast numbers of troops but had also captured elephants, horses, weapons, and supplies from towns to the east, west, and north. Allowing the Burmese to establish permanent encampments for a prolonged siege would make them difficult to defeat, so Ayutthaya should seize the opportunity to attack before the Burmese consolidated. The king responded that even if the capital’s forces did not launch a preemptive strike, the Burmese, positioned to the north and west, would be forced to retreat with the arrival of the flood season, at which point counterattacks could recover spoils and captives. Burmese chronicles repeatedly record that the inhabitants of the capital defended against Burmese attacks with determined resistance, preventing the enemy from approaching the walls. Consequently, Mahanoratha advised his commanders to employ the strategy used by Mahawthata to abduct Queen Pancala Candi, which involved secretly digging tunnels into the city. This tactic was ultimately used, as it allowed forces to avoid being targeted by Ayutthaya’s defenses. The chronicles report five tunnels in total, and on the day the city fell, the Burmese set fires at the tunnel bases to weaken the walls, then climbed into the capital using ladders at the breached points while others entered through three prepared tunnels. Immediately upon entering, the Burmese spread throughout the city, setting fires, looting temples and houses, seizing valuables, and taking captives according to their discretion. (For detailed analysis, see the commentary at the end of this chapter)

4.2 Was Thailand Well-Prepared to Concentrate Its Forces for the Defense of Ayutthaya?

In the past, Ayutthaya protected the capital with brick walls and tall fortifications surrounding a wide city area, which effectively prevented enemy assaults. Even when the Burmese army surrounded the capital, the defenses remained strong and resilient. However, the strategy of using the capital itself as a fortress to lure the enemy into a prolonged siege while waiting for reinforcements from provincial towns had long become ineffective. The new defensive strategy, as used by King Naresuan the Great, was widely accepted: the key was to push back the enemy and prevent them from approaching the capital. (Nithi Eawsriwong, 1997: 137)

Sunet Chutintharanon (2000: 189–191) commented that the strategy of using the capital as a defensive base continued to serve as a fundamental defensive tactic in wars against Burma in late Ayutthaya, including the 1762 campaign against Alaungpaya and the 1767 war resulting in the city’s fall. Particularly in 1767, Burmese chronicles—whether the Ho Kaew or Mannan Mahayazawin Thokeji, and the Konbaung royal chronicle—agree that King Ekathat of Ayutthaya devised a plan to delay the Burmese siege until the flood season. When the rising waters forced the Burmese to retreat, Ayutthaya could counterattack to recover spoils and captives. The 1767 campaign reflects an advanced development in the defensive strategy of using the capital as a military base in Thai-Burmese warfare, as it was the first and only time the Ayutthaya leadership preserved the city intact until the flood season, sparing the walled population from severe shortages.

The effective deployment of defensive lines prevented the Burmese army, which had besieged the capital for over ten months from February 1766, from approaching the city walls or establishing artillery positions as they had done in the Alaungpaya campaign. At most, they could set up distant encampments, such as from the west near Wat Tha Karong, while much of their forces remained in the Prachet and Phu Khao Thong fields. From the southwest, they could not reach Wat Chaiwatthanaram due to large Ayutthaya camps. From the east, they did not reach Wat Phichai, and the entire stretch from Hua Ro to the mouth of Mae Bia and Khlong Suan Phlu remained free from Burmese occupation. From the southeast and south, areas including Khlong Suan Phlu, Wat Portuguese, Wat Phutthaisawan, and Wat Saint Joseph remained under Thai control. To the north, the Burmese advanced no farther than Pho Sam Ton and Pak Nam Prasop.

Phraya Boran Ratchathanin recorded: “…When the Burmese approached the capital, capable officials commanded troops to resist. However, Thao Phraya Senabodi, unlike Phaya Yommarat, did not engage in battle. Stationed at Nonthaburi, once the Burmese captured Thonburi, English merchant ships retreating caused Phaya Yommarat’s forces to withdraw without fighting. Phraya Phra Khlang, leading 10,000 men, attacked the Burmese camp at Wat Pa Fai, Pak Nam Prasop. The Burmese fired, killing four to five Thai soldiers, causing the army to retreat. Two or three days later, he was ordered to attack the same camp again; before combat commenced, the Burmese lured the Thai forces closer and ambushed them, causing the main army to collapse and retreat into the city.” (Thuan Bunyaniyom, 1970: 37)

In naval combat, the Royal Chronicles note that when defenders saw the enemy’s artillery could reach the city, they dispatched the navy to attack the Burmese camp. This naval force consisted of six regiments of volunteers. It is recorded that a man named Ruek, carrying a double-edged sword, led the attack at the front of the boats. When the Burmese fired, Ruek fell into the water, and the entire navy retreated back into the city.

On reflection, it appears to have been due to belief in occult practices. The man Ruek seemed to act as a ritual master who performed a sword dance and blew charms at the front of the army, believing he could protect the whole force. When the ritual master was struck down by cannon fire, the naval troops became demoralized. The commanders who led the expedition, seeing that to engage the enemy further would likely be a suicidal venture and pointless, ordered a withdrawal. This episode serves as a warning that excessive reliance on superstition can lead to defeat.

A French missionary summarized the fighting ability of the Thai troops defending Ayutthaya by observing that whenever the Thais sallied forth to fight the Burmese, they only served to furnish the enemy with arms. When the rainy season arrived, some Burmese commanders complained to Mahanoratha that heavy rains and the imminent floodwaters would make continued operations difficult and asked to withdraw temporarily, returning to attack Ayutthaya after the dry season. Mahanoratha disagreed, arguing that Ayutthaya was already suffering shortages of food and gunpowder and was on the verge of falling; if the Burmese withdrew, the Thais would have the opportunity to reinforce and better prepare their defenses, making any subsequent assault harder. Therefore he refused to retreat, ordering scouts to seek high ground such as mounds and temple sites around the capital, dividing responsibilities to establish flood-season camps, dispersing elephants, horses, and transport animals to graze on elevated ground in nearby towns, and assembling a large number of boats of all sizes to be used by the army.

(Image from the book The Fall of Ayutthaya, Second Time, B.E. 2310)

When the Burmese army had completed preparations for campaigning during the rainy season and the flood season, Mahanoratha fell ill and died at the camp in Ban Si Kuk. However, Mahanoratha’s death turned out to be disadvantageous for the Thai side. Previously, the northern and southern Burmese armies often competed with each other, operating independently. After Mahanoratha’s death (according to Burmese sources, he likely died around late December 1766 or early January of the following year), Ne Myo Sithu became the supreme commander, taking full control of the entire army. As a result, the northern and southern forces coordinated and jointly surrounded Ayutthaya. Ne Myo Sithu moved his headquarters from the Paknam Prasob camp to the Pho Sam Ton camp.

Consideration:

Thai chronicles agree that Mahanoratha died of fever, though the timing varies significantly, almost as if he died before the flood season. In Turpin’s History of Siam, it is noted that Mahanoratha’s death occurred five days after Thai envoys returned from peace negotiations (Sunet Chutintharanon, 1998: 63). Some claim it was an act by Ne Myo Sithu, who had previously been in conflict with Mahanoratha. Despite their disagreements, Mahanoratha had ultimate authority in decision-making, even regarding the siege of Ayutthaya and the use of underground tunnels to enter the city. There is no evidence that the two Burmese armies lacked coordination; on the contrary, they continuously supported each other. Therefore, Mahanoratha’s death did not alter the situation for Ayutthaya.

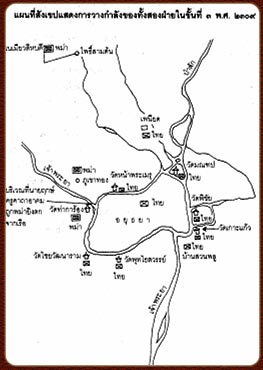

At the outset of the campaign, the war was divided into four stages. The first stage was termed “raiders plundering various towns,” which might sound like a one-sided accusation. However, as events unfolded, the Burmese themselves acted exactly as described, confirming that this designation reflects reality rather than a biased claim (Janya Prachitromrun, 1993: 175–176). Around the capital, Ne Myo Sithu ordered the vanguard to establish camps at Wat Phu Khao Thong, then at Wat Tha Kharong, and continued along Wat Krachai, Wat Plabplachai, Wat Tao, Wat Suren, and Wat Daeng on the western side, placing cannons to fire into the city.

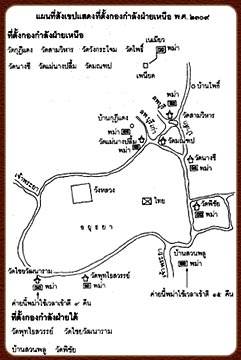

As for the Thai defensive camps, the Thais later established positions to protect the capital in all directions as follows:

North: Camps at one of the cremation temples and at Pheniat.

South: Camps at Ban Suan Plu, with Luang Aphai Phiphat and 2,000 Chinese troops under a Chinese commander (some manuscripts call him Nai Kai), and a Christian camp at Wat Phutthaisawan.

East: Camps at Wat Ko Kaew, Wat Monthop, and Wat Phichai under the command of Phraya Wachiraprakarn (Sin).

West: The Six Volunteer Regiments established a camp at Wat Chaiwatthanaram.

(Image from the book The Fall of Ayutthaya, Second Time, B.E. 2310)

The Thai army defending the capital began to fall into disorder, realizing there was no way to defeat the Burmese. The Chinese troops stationed at Ban Suan Plu camp sought to save themselves first. About 300 of them conspired and went to the Buddha Foot to strip the gold covering the small mandapa and the silver sheets on the floor of the large mandapa, dividing the spoils among themselves, and then set fire to the mandapas at the Buddha Foot, intending to cause destruction (Lieutenant General Ruamsak Chaikomint, King Taksin the Great, Supreme Thai Marine Commander, in Through Battles Special Edition: Veteran’s Day, 3 February 1994, p. 17). Later, the Chinese camp at Ban Suan Plu fell to the Burmese. Soon after, the Burmese attacked the Peniat camp, where Ne Myo Sithu, the Burmese commander, established his headquarters, directing the Burmese army to assault the camp. The Thai forces stationed to defend the northern side of the capital were defeated, and all northern camps retreated back into the city.

The Burmese set up camps near the northern capital at Wat Khudi Daeng, Wat Sam Phihan, Wat Sri Pho, Wat Nang Chi, Wat Mae Nang Pluem, and Wat Mandop, building war towers and firing cannons into the city daily.

On the southern side, they attacked Wat Phutthaisawan and Wat Chaiwatthanaram, capturing the camp after eight to nine days. Phraya Taksin had already abandoned his camp at Wat Phichai before the Burmese arrived.

Wat Phanan Choeng, located at the confluence of the Pasak and Lopburi Rivers with the Chao Phraya River, known as the Bang Kacha whirlpool area, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya Province.

(Image from the book History of Siamese Society and Culture, Thailand)

Phra Chao Phanan Choeng, the principal Buddha image in the main hall of Wat Phanan Choeng, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya Province. According to the Royal Chronicles in the Luang Prasert Akson Niti edition, it was constructed before the establishment of Ayutthaya as the capital, serving as an important temple for 26 years, dating back to the Ayodhya-Sriramthep Nakhon period.

(Image from the book History of Siamese Society and Culture, Thailand)

Ominous Signs (from the Royal Chronicles of the Old Capital, p. 175) — As the fall of Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya approached, various ominous signs occurred. The large Buddha image at Wat Phanan Choeng (Phra Chao Phanan Choeng) shed tears; the Tikolkanat Buddha image, carved from the Bodhi tree, split into two parts; the life-sized golden Buddha and the Surin Buddha cast in tin at Wat Phra Si Sanphet in the royal palace showed signs of sorrow, with their eyes falling onto their hands. Two crows fought, one swooping onto the top of the Chedi at Wat Phra That, as if impaled there. The statue of King Naresuan wept and emitted loud sounds of thunder multiple times. Members of the royal family and officials were disordered and failed to uphold proper conduct, showing signs that the capital was doomed to fall. Within the city, under prolonged Burmese siege, supplies ran short, and banditry and looting increased.

On Saturday, the 4th day of the second lunar month, Year of the Dog (corresponding to 4 January 1766), a fire broke out at night in the capital, starting from Tha Sai along the northern city wall, spreading through Khao Pluak Gate, reaching the coconut grove district, then to the Thon, Tan, and Ya forest areas, burning Wat Maha That, Wat Ratchaburana, and Wat Chattatan, including monks’ quarters and houses, totaling approximately 10,000 structures.

The people suffered severe hardship. King Ekathotsarot sent envoys (Phraya Kalahom and other officials) to the Peniad camp to request a ceasefire and offer vassalage to King Mangra. Ne Myo Sihabodi, the Burmese commander, refused, intending to seize all the wealth of the people. According to Burmese chronicles, Ne Myo Sihabodi attempted multiple attacks on the capital but failed each time because the Thais, though cornered, fought vigorously, repelling the Burmese. Eventually, the Burmese established a blockade again. Inside the city, the starving population attempted to flee by scaling the walls—some succeeded, others were captured but provided food.

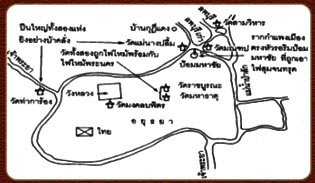

Seeing the citizens weakened and scattered, Ne Myo Sihabodi ordered the Burmese forces from Wat Khudi Daeng, Wat Sam Phihan, and Wat Mandop to converge at night, building a rafts-bridge (a bridge of woven wood) across the river at Hua Ro near the northeastern corner of the city, where the river was narrower. Palm wood was used to build forward positions (to gradually advance toward the enemy), shielding soldiers from the city’s artillery. Once the rafts-bridge was completed, the Burmese set up a camp at Sala Din outside the city, then dug tunnels toward the city wall, piling firewood beneath the foundations, preparing ladders to climb the walls, and readied to storm, loot, and seize the city.

Tunnel digging (Ayutthaya, Hua Ro, 1666 BE / 2309 BE) in the Konbaung Burmese chronicles: The plan to dig tunnels was set in motion after the Burmese commanders were certain that the Ayutthaya forces had significantly weakened and the city’s population was suffering from severe hunger. They decided to start tunneling under the city walls at Hua Ro, the narrowest point of the moat. There were a total of five tunnels: two of them were dug only to stop directly beneath the base of the walls, then extended along both sides of the walls to a length of approximately 350 yards. Timber supports were placed under the tunnels to reinforce the wall foundations. The remaining three tunnels were dug beneath the walls into the heart of the city, but about two feet of soil remained covering them. This tunneling operation did not proceed smoothly, as Thai forces on the ramparts continuously fired at the Burmese troops approaching the wall, forcing the Burmese to conduct the work in carefully staged steps.

(Image from the book The Fall of Ayutthaya, Second Time, B.E. 2310)

Bridge Construction: At the initial stage, the Burmese built a bridge across the moat, and then constructed three new camps close to the northern side of the city’s moat. Once these were completed, they began digging tunnels. The Burmese chronicles note that the Thais did not ignore these operations. In response, Phra Maha Mantri (or Chamuang Si Srisarak in Thai-Burmese Wars) volunteered to attack the three Burmese camps that had been established nearby. King Ekathat ordered a force of 50,000 men and 500 elephants to be deployed. It was reported that Phra Maha Mantri fought courageously and succeeded in capturing all three Burmese camps, but later the Burmese sent reinforcements to encircle the Thai army, forcing Phra Maha Mantri to withdraw back into the city. The Ayutthaya chronicles briefly mention the same event, stating that the Burmese attacked and burned the Phra Thi Nang Peniad, then established camps at Peniad, Wat Sam Wihan, and Wat Mandop. They then built a bridge across the embankment to begin digging tunnels at the base of the walls, set up the Saladin fort, established a camp at Wat Mae Nang Pluem, erected a high fort to mount cannons, and finally built another camp at Wat Sri Pho.

Considerations:

- 1. The strategy the Burmese employed in this campaign was to besiege the capital, remaining in place even during flooding, and to carry out the following operations:

– Seize and gather as much provisions as possible from the surrounding areas for reserves.

– Collect cattle and livestock that were captured and cultivate crops in the surrounding land.

– Relocate elephants and horses to areas with abundant forage.

– Have the troops surrounding the capital construct fortifications and camps in areas not affected by flooding.

– Establish guard units at intervals between the forts to maintain defense.

– Intercept and block any external forces attempting to come to aid the city.

- 2. In the final strategy to capture the capital, the Burmese shifted from using ladders to scale the walls to digging tunnels beneath the walls, proceeding in the following stages:

1) Constructing bridges

2) Building forts and camps

3) Digging the tunnels

Some documents mention that the Burmese built three new forts near the northern moat of the capital to divert the Thai forces’ attention from the tunneling operation, but this is not recorded in the Konbaung Burmese chronicle.

The construction of these three new forts had three main purposes:

1) To coordinate with the tunnel-digging operations and prevent the Thai soldiers on the ramparts from effectively firing at the Burmese troops who were digging the tunnels.

2) To increase the destructive impact on the Thais inside the capital by bombarding them.

3) To support the troops who would storm the walls or enter the capital through the tunnels.

The strategy the Burmese employed in this war was to completely encircle Ayutthaya, isolating it so that it had to rely on itself and face severe shortages of food and supplies. They did not allow reinforcements from the provinces to intervene. Moreover, the Burmese did not allow natural conditions, such as the flooding season, to hinder their siege operations, as had been the case in previous campaigns. The Ayutthaya forces did not anticipate that the Burmese could overcome the challenges of the flood season, unaware that the Burmese already had a fleet and engineering troops with materials for shipbuilding, enabling them to counter the Ayutthaya naval forces that might have taken advantage of the flooding to launch attacks. According to the Burmese chronicles, the Ayutthaya navy was strong in both quality and quantity, yet the Burmese were able to hold their own without disadvantage. The chronicles provide a fairly detailed account of the naval encounters between the Thai and Burmese forces (Wisetsai Si, 1998: 202). It is clear that what the Ayutthaya military commanders could not anticipate—and could not have anticipated—was that the Burmese would adapt their strategy for capturing the capital, refusing to allow natural conditions to impede military operations. Even during the flood season, the Burmese maintained a tight siege around the city, forcing Ayutthaya to suffer from famine and eventually leading to its defeat.

- 3. The presence of enemy forces encircling Ayutthaya was already a grave threat, and the outbreak of fires that burned houses made the situation far worse. Existing shortages and scarcities were compounded, adding misery upon misery; the populace suffered terribly, with over 10,000 houses destroyed, leaving tens of thousands homeless. Seeing people facing death, lacking shelter and food, their morale and physical strength declined. King Ekathat therefore negotiated with the Burmese to seek an end to hostilities and to accept vassalage to the King of Ava, but the Burmese commanders refused, intent on seizing the people’s possessions entirely.

- 4. The Burmese steadfastly maintained their original objectives in this campaign from the beginning until now, even at a point when the war could have been ended. The Thai side, seeing that the situation had reached its limit, offered to surrender and accept vassalage, as had been customary since ancient times. However, the Burmese refused, because the Thai surrender was not their goal. The Burmese aimed to seize the wealth and people of Ayutthaya rather than merely to make Thailand a vassal state. Therefore, when the Thai side offered surrender and vassalage, the Burmese ignored it, as the proposal did not align with their original intentions.

- 5. The Final Assault as Ayutthaya Was About to Fall

Situation of the Thai side: The Thai forces were already severely weakened.

Target: The area by the Mahachai Fort, at the northeastern corner of the city, where the river was narrower than at other points.

Time of Operation: Night

Operations carried out: Palm wood was used to build advance camps and a pontoon bridge.

Thai counteraction: The Thai forces were able to repel the attackers vigorously.

6. Fall of Ayutthaya – Operations:

Target: Hua Ro, near the Mahachai bastion

Time: Started at 3 PM, Burmese entered the city by 8 PM on April 7, 2310 BE

Operations: The Burmese completed the bridge, dug tunnels under the wall foundations, and set fire to weaken the walls. The walls collapsed by 8 PM, allowing the Burmese to climb in with ladders.

Duration of the siege: The Burmese besieged Ayutthaya for 1 year and 2 months.

(Janya Prachitromrun, 1993: 170–171)

Map of the Situation at the Fall of Ayutthaya, 2310 BE

(Image from the book: The Fall of Ayutthaya, Second Time, 2310 BE)

4.3 How was the second siege of Ayutthaya different from the first siege?

The loss of independence by Ayutthaya this time, historians say, shows that the Burmese campaigns under King Bayinnaung and King Maha Nara were different.

During King Bayinnaung’s campaign, the Burmese waged war as a monarch. Ayutthaya suffered the first loss of the city to Burma, but the damage was not extensive, as Bayinnaung’s warfare emphasized consolidating the unity of the Burmese-Pagan empire rather than raiding and destroying enemy towns (Piset Chiachanpong, 1999: 3560). In contrast, during King Mahā Nārā’s campaign from Ava, the Burmese acted more like raiders. Lacking the strength to storm the capital directly, they spent three years conducting looting operations around the city before finally capturing Ayutthaya. The Burmese chronicles, particularly the Konbaung version, are considered more reliable than previously assumed by Thai historians (Tin Ohn, “Modern Historical Writing in Burmese, 1724-1924,” in D.G.E. Hall, Historians of South-East Asia, London: Oxford University Press, 1962), as they were based on thorough examination of primary sources. Moreover, Burmese sources do not contradict the points mentioned in the Thai royal chronicles.

External intervention also played a role. Ethnic groups seeking independence often leveraged external powers to counterbalance a central authority. One such external influence that disrupted Burmese political unity was Ayutthaya itself, especially in the 22nd Buddhist century. During the Ban Plu Luang dynasty, Mon refugees entered Ayutthaya as a form of resistance against Burmese central authority. Although King Borommakot aimed to sustain Burmese weakness rather than strengthen the Mon, this policy inadvertently interfered with Burmese internal politics, as Mon laborers within his kingdom could potentially return to an independent Mon state if it succeeded in breaking free from Burmese control.

It was thus common that whenever the Burmese central authority became strong, it would assert influence over Ayutthaya to prevent the city from becoming a refuge for minority groups, including those from Lan Na or eastern Shan territories at certain periods.

For strategic reasons, after the Alonpaya campaign in 1760 (B.E. 2303), Ayutthaya began to act as a protector for Burmese minority groups. This was part of its self-defense strategy: by recognizing the threat of the Alonpaya dynasty, Ayutthaya sought to push that power away from its core territories, establishing satellite areas as buffer zones.In 1761 (B.E. 2304), Ayutthaya sent troops north to assist Chiang Mai, which had requested refuge under royal patronage, but it was too late (Ayutthaya Royal Chronicles, Phra Wanrat edition: 642). Even in 1764 (B.E. 2307), when Hui Tongja, ruler of Tavoy, rebelled against Burma and fled with his family to Mergui, Ayutthaya decided to accept him under its protection (Thai-Burmese Wars, 1964: 311).

King Mangra’s reign began with the suppression of rebellions across the outlying regions. Ayutthaya’s interference within the traditional sphere of influence of the Alaungpaya dynasty effectively encouraged uprisings in various Burmese provinces. For this reason, King Mangra found it necessary to diminish Ayutthaya’s power. The objective of this war, therefore, was not merely to expand royal dominion by making Ayutthaya a vassal; the true aim was to break apart or so weaken the Ayutthaya kingdom that it could no longer shelter Burmese subject towns. In the view of the old capital’s residents, Ayutthaya’s decision to harbor Hui Tongja and not surrender him to Burma when requested was the immediate cause of this final war (Accounts of the Old Capital, 1967: 167), which is not implausible when the whole Thai–Burmese relationship system is considered.

The Burmese army that moved in from B.E. 2307 (1764) had no king personally commanding it, and for that reason it has often been dismissed as “not a royal army.” But the notion of what constitutes a royal army is itself ambiguous. King Mangra’s intent to attack Ayutthaya may have existed from the moment he ascended the throne in B.E. 2306 (1763); he had served in his father’s expedition against Ayutthaya in B.E. 2303 (1760) and, upon accession, organized his administration to enable multiple and sustained military campaigns. His experience campaigning in Siam revealed Ayutthaya’s weaknesses and allowed him to prepare what was necessary for later victory over the kingdom.

That King Mangra did not personally lead the expedition against Ayutthaya was due to other obligations. If one assesses the threats confronting Burma — between Ayutthaya and Manipur — it is clear that Manipur posed a danger by cavalry, while Ayutthaya mainly threatened Burma through its influence over frontier principalities. The Konbaung chronicle states explicitly that when Ne Myo Sithu reported Ayutthaya was within reach, King Mangra ordered that, once Ayutthaya was taken, the city should be utterly destroyed and the king and royal family sent to Burma.

The Burmese plan to conquer Ayutthaya was to advance forces from both south and north. King Mangra judged that Ayutthaya was strong and had not been seriously weakened by war for a long time; therefore a single northern expedition under Ne Myo Thihapate would be insufficient. He therefore instructed Mahanoratha to lead a second army from the southern route to assist in the operation.

Both armies had other missions to accomplish first, but these were meant to support the main objective: the attack on Ayutthaya. Ne Myo Sithu’s army advanced through the Shan towns to conscript soldiers and then moved toward Chiang Mai via Chiang Tung. He was tasked with suppressing rebellions in Lanna, which he accomplished swiftly. By the end of the rainy season in B.E. 2307 (1764), he had subdued all of Lan Xang, and then stayed the rainy season in Lampang in B.E. 2308 (1765), conscripting people from Lanna, Lan Xang, and the eastern Salween princes to join the army in preparation for the campaign against Ayutthaya.

Ne Myo Sithu’s army moved from Lampang in the dry season of B.E. 2308. Meanwhile, Mangmahanar-Tha had to deal with rebellions in Tavoy first (it was impossible to attack Ayutthaya while leaving Tavoy in revolt), and stayed through the rainy season of B.E. 2308. During this time, they conscripted soldiers from Pegu, Martaban, Mergui, and Tavoy-Tenasserim. When the dry season arrived, both forces marched into Siam to converge at Ayutthaya as planned.

It is evident that the two Burmese forces did not move simultaneously, due to the long distances to Ayutthaya. In addition, the towns they encountered along the way differed. The southern army faced smaller towns, except for Phetchaburi, encountering few major obstacles, while the northern army had to deal with several large towns such as Phitsanulok, Sawankhalok, and Phichai, possibly including Kamphaeng Phet. Therefore, the southern army reached the vicinity of the capital sooner, while the northern army took much longer. Thai sources reflect this staggered movement, noting that the southern army had more time and spent it looting and capturing people from towns like Kui, Pran, Phetchaburi, Ratchaburi, Kanchanaburi, Nakhon Chai Si, Suphan, Thonburi, and Nonthaburi.

A French missionary stationed in Ayutthaya at the time reported that the Burmese invaded Ratchaburi and Kanchanaburi as early as March B.E. 2308, but the armies did not reach the capital’s vicinity until September 14, B.E. 2309 (1766). For over a year, the Burmese encamped at the confluence of the two rivers (noted as Tok Ra-Om and Dong Rang Nong Khao in Thai chronicles), building warships there to prepare for the campaign before finally attacking Ayutthaya. (The Royal Chronicles, Royal Letters Edition, Vol. 2: 263)

The northern army under Ne Myo Sithu presents some discrepancies between Thai and Burmese sources regarding strategy. According to the Glass Palace Chronicle, the first city captured was Ban Tak, which resisted the Burmese but was eventually taken, looted, and its ruler captured. (This clearly contradicts Thai chronicles, which mention a commander named Phraya Tak campaigning in Ayutthaya during the siege.) Following Ban Tak’s defeat, Rakhang and Kamphaeng Phet surrendered peacefully to avoid being plundered as Ban Tak had been.

From Kamphaeng Phet, the Burmese forces split to attack Sawankhalok, which resisted but fell, and the ruler was taken captive. They then advanced to Sukhothai, where the ruler submitted (contradicting Thai chronicles that mention the population fleeing to the forest and returning later to attack the Burmese with the Phitsanulok forces). Next, the Burmese moved to a city called “Yazama” or “Rasama” in the Glass Palace Chronicle, whose ruler also submitted. The army then proceeded to Phitsanulok, a major city, whose ruler resisted but was defeated and captured. (This conflicts with both Ayutthaya and Thonburi Thai chronicles, as Phitsanulok did not fall to the Burmese, and the governor of Phitsanulok later claimed authority.) The Burmese stayed in Phitsanulok for ten days and then subdued other northern towns, including “Lalin” (unknown), “Peksa” (Phichai), “Thani” (possibly Ban Kong Thani, a later Sukhothai), “Biksek” (Phichit), “Kunwansan” (Nakhon Sawan), and “Inthong” (Ang Thong), none of which resisted. The Burmese conscripted soldiers and resources from all these towns to join the campaign against Ayutthaya.

In this campaign, both armies stayed during the rainy season at the edge of the royal territories—Lampang and Tavoy—allowing time for preparation and planning the long campaign. The Burmese aimed to isolate Ayutthaya from potential reinforcements from vassal towns, exploiting the kingdom’s weakest points.

The strategy used by both Burmese armies to subdue towns was consistent: cities that resisted were plundered and their people taken captive as punishment; cities that submitted peacefully were only conscripted for manpower and resources without punishment. The Burmese also deployed forces to coerce local populations. Several sources note that Thai villagers in central western river plains “cooperated with the Burmese” (e.g., the Royal Letter Chronicles), with some even volunteering to join the Burmese army. A French missionary reported in B.E. 2308: “…rumors circulated that the Burmese army was full of Thai people, who, suffering, turned from the Thai to join the Burmese…” Through this approach, despite initially modest manpower, the Burmese could encircle and eventually conquer Ayutthaya, a success made possible by the collapse of Ayutthaya’s defensive and administrative systems.

The two Burmese armies converged in late B.E. 2308, with the northern army stationed less than two kilometers from Ayutthaya. They continued to spread out, coerce, and suppress surrounding towns. At this time, villagers still fled into the capital in large numbers daily, and supplies remained sufficient, as recorded by a French missionary: by September 14, B.E. 2309, when the Burmese tightened the siege, food in the city was still abundant, with only beggars starving. (Collected Chronicles, Vol. 39, 1965: 414)

From September 14, B.E. 2309, until the capture on April 7, B.E. 2310, Ayutthaya fell, though the kingdom had effectively collapsed even before the walls were breached. External forces had already shattered ties between the capital and its provinces, leaving Ayutthaya unable to resist as a united kingdom. Some chaos and weakness could be attributed to leadership failures, but the primary cause was the collapse of Ayutthaya’s political and social system.

Amid this vulnerability, Ayutthaya had been cut off from its provincial towns for nearly two years, leaving no central government to maintain cohesion. The Burmese victory came from the complete destruction of Ayutthaya’s kingdom; the eventual capture of the city was merely an inevitable outcome. (Veena Rojanratha, 1997: 132–137)