King Taksin the Great

Chapter 3: The Alaungpaya Dynasty and the Invasions of Siam

Map of Burma

(from the book Maharachawong: The Burmese Chronicle, copied from A Wonderland of Burmese Legends)

Mandalay Palace

(photo from www.ayeyarwady.com/Photo-e/old_burma/sh042101.htm, July 20, 2004)

3.1 Which Burmese king led the invasion of Ayutthaya in 1764, and what was his background?

Map of Burma

(from the book Maharachawong: The Burmese Chronicle)

The king who led the invasion that brought about the fall of Ayutthaya in 1767 was King Hsinbyushin (1753–1776), a monarch of the Alaungpaya Dynasty. There were a total of eleven kings in this dynasty, namely:

- 1. Alaungpaya (1691–1760)

- 2. Naungdawgyi (1760–1763), also known as Manglok or Manglong

- 3. Hsinbyushin (1763–1776), also known as Mangra, Maydu Meng, or Chingpiyucheng, the “Lord of the White Elephant,” younger brother of Naungdawgyi (During his reign, Ayutthaya was captured and later restored)

- 4. Singu (1776–1781) (Siam remained at peace for ten years)

Note

Before his death, King Alaungpaya declared that the throne should be passed among all his sons in order of seniority. However, King Hsinbyushin did not follow this royal command and instead granted the throne to his son Singu, even though he still had four younger brothers: (1) Mangpotakaing Abyin, (2) Mangwengtakaing Padung, (3) Mangjutakaing Pagan, and (4) Mangkochiang Takaingtangtale. Singu had Mangpotakaing Amien executed and placed the other three uncles under control in provincial towns. He later dismissed Azaewun Gyi from his position. Singu indulged excessively in wine and women; on one occasion, when his chief consort displeased him while he was drunk, he ordered her to be drowned and stripped her father, Atwan Ngun, of his noble title, demoting him to commoner status. Resentful, Atwan Ngun conspired with Prince Takeng Padung to assassinate King Singu. Afterward, Prince Takeng Padung ascended the throne under the title King Bodawpaya (Bodaw Mintaya Gyi).

(http://www.worldbuddhism.net/buddhism-history/Burma.html, July 14, 2004)

- 5. Maung Maung (1781–1781)

- 6. Bodawpaya (1781–1819), also known as Padung (He began the war with Siam in 1785, known as the Nine Armies War)

Note

King Bodawpaya is regarded as the last great monarch of Burma. After ascending the throne, he moved the royal capital to Amarapura, which he ordered to be newly constructed. He led his army to subdue Manipur and invaded the kingdom of Arakan in 1785, the same year Bangkok was founded. During the Arakan campaign, the Burmese brought back a revered Buddha image from the city of Arakan known as the Maha Muni Buddha, a bronze image in the attitude of subduing Mara with a lap width of five cubits and one span. It was originally cast in 689 CE during the reign of King Chandrasuriya of Dhammapura in the kingdom of Arakan. Earlier Burmese kings, such as King Anawrahta, had attempted to bring this sacred image to Burma but were hindered by obstacles. On this occasion, the Burmese succeeded by dividing the statue into three sections for transport.

Takhe (wheeled handcart)

(photo from http://www.cd-ironworkers.co.uk/misc/trolley2-50.jpg)

On this occasion, the statue was divided into three sections and placed on a takhe (or takheh), a type of low wheeled cart used in ancient times for hauling or pushing heavy objects, such as large boats being drawn ashore or moved into a dock (Wiboon Leesuwan, 2003: 165). It was then hauled across the mountains into Burma. King Bodawpaya ordered the construction of a temple to enshrine and venerate the image. This Buddha image has since been revered by the Burmese people above all others in the country to this day.

(http://www.worldbuddhism.net/buddhism-history/Burma.html, July 14, 2004)

- 7. Bagyidaw (1819–1837)

- 8. Tharrawaddy Min (1837–1846)

- 9. Pagan Min (1846–1853)

- 10. Mindon Min (1853–1878)

King Mindon

(photo from the book Thai Tiew Phama)

Depiction of the king presiding over state affairs on the Lion Throne

(photo from http://www.4dw.net/royalark/Burma/burma.htm)

11. Thebaw (1878–1885) (M.R. Saengsom Kasemsri and Wimon Pongpipat, History of the Rattanakosin Period, Reigns I–III (1782–1851), 1980: 37)

Burmese Princess

King Thibaw and Queen Supayalat

(photo from the book Burma’s Fall)

Ladies-in-waiting during the reign of King Thibaw

(photo from the books Burma at War with Siam and Burma’s Fall)

Alungpaya Dynasty

1. Alaungpaya

1711-1760

2. Naugdawgyi

3. Hsinbyushin

6. Bodawpaya

1736 – 1776

1736 – 1776

1745 – 1819

5. Maung Maung

4. Singusa

Insae

1763 -1782

1756 – 1782

1762 – 1808

8. Tharawaddy

1786 – 1846

1786 – 1846

7.Bagyidaw

1784-1846

9. Pagan

Kanuang

10. Mindon

1811-1881

1819-1866

1814 -1878

Limbin

11.Thibaw

Son

+ 1933

1858-1916

Son

Son

Richard Limbin

Thura Limbin

Maung Maung U

Maung Maung Gyi

1902-

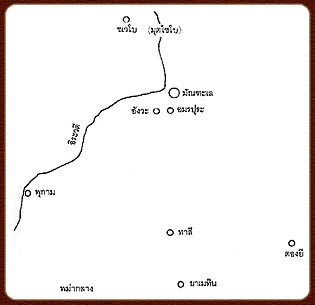

Map showing the location of Mokchobo Village, now called Shwebo, also known as Rattasingha, and the city of Ava

(photo from the book The Fall of Ayutthaya)

The Alaungpaya Dynasty (the term Alaungpaya means “Bodhisatta,” according to Thuan Boonyaniyom, 1970: 34). The Glass Palace Chronicle recounts that the dynasty, founded by King Alaungpaya, originated from Mang Ongzeya (where Ong means “victory,” and Zeya corresponds to “Chaiya”; in Burmese pronunciation, he was called Mong Ongzeya), who was born into a family of hunters from the northern region of Ava.

Mang Aung Zaya became the headman of Shwebo Village, also known as Mokchobo or Mukchaibo, meaning “Hunter’s Village.” The Burmese later called it Mokchobo, which eventually became the town of Rattasingha. It was located about 2,000 sen (approximately 97.53 kilometers) from Ava and had around 200 households. It is said that Mang Aung Zaya was a man of great strength and courage, skilled in magic and the art of warfare, and was highly respected and obeyed by the people. When the Mons came to power in Ava and sent officials to collect taxes as usual, Mang Aung Zaya gathered his followers and fought back, killing all the Mon officials. No matter how many times the Mons sent troops to suppress him, they were defeated each time. (Chao Rup Thewin, 1985: 638)

In 1714, Maung Aung Zaya began to resist the Mon by gathering about forty followers and raiding a Mon unit that came to collect tribute (Janya Prachitromran, 1993: 4). From 1752 onward, Maung Aung Zaya gained increasing fame through successive victories over the Mon, which attracted more Burmese people to join him. In December 1753, he captured the city of Ava. Three years later, in 1755, Maung Aung Zaya was acclaimed King of Burma under the name Alaung Mintaya Kyi (Chusiri Chamroman, 1984: 61). He seized Dagon, a coastal city held by the Talaing (Mon), renamed it Rangoon, and established the city of Ratanasingha (known in Thai as Rattanapura Angwa) as his capital. Within two years, he subdued the northern regions such as Pathein and Syriam, and went on to capture the city of Hongsawadi (in 1757). The details are as follows.

Fearing King Alaungpaya, the ruler of Hongsawadi agreed to send his daughter, Meik-hkum, who had previously been betrothed to Smind Talapun, to Alaungpaya. Smind Talapun, angered by this, led his followers out of Hongsawadi. When Alaungpaya received the princess, he demanded that the key Mon officers be handed over as hostages. The ruler of Hongsawadi refused, which greatly angered Alaungpaya and led to another war. Eventually, Hongsawadi fell in 1757, and Alaungpaya ordered the city to be burned. After burning Hongsawadi, he captured a large number of Mon people as prisoners and relocated them to Ava (Ratanasingha). From that time onward, the Mon nation was completely absorbed into Burma, and the final period of Mon independence lasted only seven years. (http://www.worldbuddhism.net/buddhism-history/Burma.html, July 14, 2004)

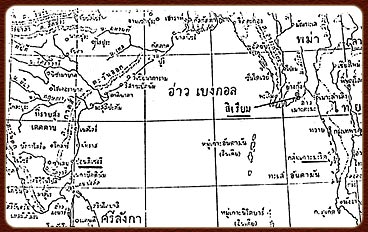

Map showing the location of Syriam

(photo from the book The Fall of Ayutthaya in 1767)

At that time, a Mon noble who had formerly been a commander under the ruler of Hongsawadi and was still in hiding saw an opportunity and led his followers to plunder Syriam. Nearby Burmese generals learned of this and marched to retake the city. The Mon leader, realizing he could not resist, gathered his valuables and attempted to escape by French ships, intending to sail to Pondicherry. However, the ships were blown off course to the eastern coast and took refuge at Mergui in Thai territory. The Burmese sent a letter to the governor of Tavoy claiming that the Mon leader was a rebel and that the Europeans had helped him escape, requesting that Thailand apprehend both the man and the ships. Thailand replied that the French ships had been driven ashore by a storm and sought shelter for repairs at Mergui, and there was no reason to seize the vessels.

After the repairs were completed, Thailand allowed the ships to leave. King Alaungpaya, upon learning of this, was displeased with Thailand but remained passive (Janya Prachitromran, 1993: 4). Meanwhile, Smind To fled to Chiang Mai. King Alaungpaya then launched a campaign into the inland Mon towns near the Thai border, capturing Mon territories that had been vassals of Ayutthaya, including Tavoy, Mergui, Tavoy, and smaller towns in the region. Many Mons fled to seek refuge in Thailand, as the Mon kingdom collapsed under Burmese domination. The rulers of Martaban, Mon nobles, and local princes in the Tai region submitted to King Alaungpaya and presented royal tribute, such as horses, fine textiles, and incense. It is notable that King Alaungpaya sought to weaken the Mon by, for example, destroying Pegu to prevent rebels from using it as a stronghold. He then proceeded to the newly established city of Rangoon (Yangon) before returning to Ratanasingha.

King Alaungpaya possessed extraordinary strength compared to ordinary men. Having succeeded in subduing the Mon, he rested for only one year before leading his army to brutally suppress Manipur. For instance, when over 4,000 villagers refused to leave their homes as ordered, he commanded that all the men in the village be executed. The governorship of Manipur was then assigned to a minister of the prince of Manipur who had fled into the forest. A stone inscription was also erected in the center of the city, decreeing that “only heirs of the royal lineage shall have the right to be prince.” After completing these actions, he returned to his capital, Ratanasingha.

In 1749, King Alaungpaya journeyed to Rangoon to perform the dedication ceremony of the hall he had built and to consecrate the Shwedagon Pagoda. He traveled with an army moving by both land and river, with princes and regional governors leading various divisions. Among them, thirteen large units marched by land through Toungoo. His second son, Sirithammaraja (called Mangra in Thai), commanded a fleet of 300 vessels with 10,000 troops. King Alaungmintaya Kyi himself led 24 divisions totaling 24,000 men, accompanied by 600 large ships. He appointed Minkong Nartha as deputy commander and had Portuguese royal guards closely attend him. The rear guard consisted of ten divisions.

Half of the forces, comprising 5,500 troops and 100 large ships, were commanded by his third son, Thado Minhla Dayaw, governor of Amyint (called Mangpo in Thai). The other half was led by his fourth son, Thado Minzaw, governor of Patung (called Mangweng in Thai) (Chusiri Chamraman, 1984: 62).

Burmese Warships

(photo from the book Burma at War with Siam)

3.2 Why did Burma under King Alaungpaya invade Ayutthaya?

After the dedication ceremony at the Shwedagon Pagoda in 1749, King Alaungpaya received news that Siam had encroached on the Tavoy region and seized four Burmese ships. This angered him, as he viewed it as an affront to his authority and prestige, prompting his decision to lead an army against Ayutthaya. However, a series of unusual events occurred—seven lightning strikes hit the city—and astrologers warned that this was an ill omen, noting that the location of Ayutthaya conflicted with the king’s astrological chart (http://www.worldbuddhism.net/buddhism-history/Burma.html, July 14, 2004). His close ministers advised against the invasion, citing misfortune in his fate, but he ignored their warnings and led his army through Martaban and Mawlamyaing, advancing toward Tavoy, Mergui, and Tenasserim. The Burmese forces captured Tavoy, Mergui, and Tenasserim with surprising ease, astonished by the weakness of the Siamese defenses. King Ekkathat dispatched two armies to confront the Burmese: one under Phra Yommarat stationed at Kaeng Tum (believed to be near the headwaters of the Tenasserim River in Burmese territory) and another under Phra Rattanathibet sent to Kui Buri. When the Burmese approached Phra Yommarat’s army at Kaeng Tum, the Siamese forces broke apart with minimal resistance.

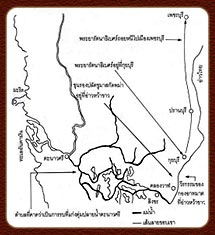

Map showing the cities of Mergui and Tenasserim

(photo from the book The Fall of Ayutthaya, Second Time)

Simplified map showing the battle of the Aratmāt forces at Wa Khao Bay, 1749

(photo from the book The Fall of Ayutthaya, Second Time, 1767)

Phra Rattanathibet, stationed at Kui Buri, learned that Phra Yommarat’s army had been defeated. He then sent Khun Rong Palat Chu, governor of Visesh Chai Charn, along with 400 troops, to confront the Burmese at Had Wa Khao on the coast. After scattering Phra Yommarat’s forces, the Burmese army advanced through the Singkhon Pass, emboldened by their success.

Tangdahmingyi

Kin Hoon Mingyi

(photo from the book Burma at War with Siam: On the Wars between Thailand and Burma)

Senior Burmese Official and Minister

(photo from the book Burma at War with Siam: On the Wars between Thailand and Burma)

Infantry and armored cavalry from the Konbaung period, followed by a group of spearmen

(photo from the book Burma at War with Siam: On the Wars between Thailand and Burma)

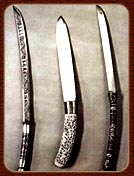

Burmese Sword

(photo from the book Burma at War with Siam: On the Wars between Thailand and Burma)

Burmese Prisoners during King Thebaw’s Reign

(photo from the book Burma Loses Its Kingdom)

Illustration of Burmese soldiers binding and rounding up prisoners

(photo from the book Maha Yazawun: Burmese Chronicles)

Khun Rong Palat Chu, a war-hungry commander, led 400 Thai troops of the Aratkhat force to defend Had Wa Khao. Facing 8,000 Burmese soldiers, both sides, confident in their strength and eager for battle, clashed in a bloody fight from morning until noon. The Burmese fell in heaps like logs, but more continued to press forward relentlessly, believing their numbers far exceeded the Thai forces. The Thai troops grew increasingly exhausted, and eventually Khun Rong Palat Chu was captured. Despite being taken prisoner, he remained invulnerable to attacks. Seeing their commander captured, the Thai soldiers’ morale collapsed. Seizing the opportunity, the Burmese deployed war elephants, crushing the remaining Thai forces, which scattered in disarray. Upon receiving the news, Phra Rattanathibet was alarmed and retreated along with Phra Yommarat’s forces. The Burmese then occupied Kui, Pran, Cha-am, Phetchaburi, Ratchaburi, and as far as Suphanburi without encountering further resistance (Niyom Sukrongphaeng, 1986: 104–105).

Considerations

1. In the battle at Ratchaburi, the Thai forces numbered 20,000, composed of soldiers from Kanchanaburi and Phetchaburi. The Burmese, however, only knew the unit commander’s name—Mang Khong Natha—and could not confirm the unit’s exact strength. Originally, during the campaigns against Mergui and Tenasserim, this unit had 8,000 troops. When King Alaungpaya reorganized the army, it was uncertain whether additional forces had been assigned to this forward unit. If the Burmese numbers were indeed only 8,000 plus reinforcements, it was unfortunate that the 20,000 Thai soldiers could not resist them, as they might have been able to delay the enemy longer and provide time for rear forces to prepare.

2. The battle at Ratchaburi appears to have been a defensive engagement by a general frontier unit. It should not have escalated into a full-scale destructive battle. Forces should have conserved strength, avoided intense fighting, and gradually withdrawn to regroup with the main army for a coordinated counterattack.

3. The preparations of King Uthumphon after Ratchaburi’s fall were hasty. Tasks such as building additional city walls and fortifications would have required considerable time and could not be completed quickly, necessitating a strategy of building defenses while simultaneously engaging in combat.

4. The Burmese pause to regroup and wait for reinforcements at Suphanburi for several days allowed the Thai forces more time and space to maneuver. Both time and territory were critical advantages for the defense of Ayutthaya at this stage.

Note: The area between Suphanburi and Pa Mok is not drawn to scale. The simplified map shows the battle at Ratchaburi as the Burmese advanced, the Thai defensive deployment at Suphanburi, and the engagement at Thung Talan

(photo from the book The Fall of Ayutthaya, Second Time, 1767)

Battle at Thung Talan (Suphanburi, 1749)

Situation: When King Alaungpaya reached Suphanburi, he paused for several days to rest and await reinforcements, as he considered his existing forces insufficient to attack Ayutthaya.

Battle: Once King Alaungpaya had assembled enough troops, he advanced to engage the forces of Chao Phraya Maha Sena, who had deployed along the Chakkarat River across the Thung Talan fields. Mang Khong Natha and the prince Mangra led the Burmese troops to attack the Thai camps, and a fierce battle ensued. The Thai forces used the river as a natural barrier, forcing the Burmese to cross under heavy fire, suffering significant casualties and temporarily retreating. When King Alaungpaya’s main army arrived with superior numbers, the Burmese executed a flanking maneuver, overwhelming the Thai forces. The Thai army was decisively defeated. Chao Phraya Maha Sena was killed in action, and Phra Yai Yommarat was wounded and later died in Ayutthaya. The few surviving commanders were Phra Rattanathibet and Phra Ratchabangsan, while a large number of Thai soldiers were killed.

The battle at Thung Talan, which was already very close to Ayutthaya, can be compared to a long-range outpost operation. The engagement did not need to result in total collapse, but the river as a natural barrier could help inflict significant damage on the Burmese forces. Thus, it was decided to fight with full strength in order to weaken the Burmese before they could reach the main stronghold of Ayutthaya. After King Alaungpaya defeated the Thai camp at Thung Talan, he advanced and reached Ayutthaya on 11 April B.E. 2303 (this engagement marked the 22nd war between Burma and Siam).

Burmese Deployment

The main army was stationed at Ban Kum, north of the capital. The vanguard, led by Prince Mangra and Mang Khong Natha, positioned at Pho Sam Ton.

Establishing the operational base, Luang Aphai Phivat, a Chinese official, brought approximately 2,000 Chinese villagers from Ban Nai Kai to volunteer in attacking the enemy camp at Pho Sam Ton. King Alaungpaya ordered Chaomuen Thip Sena, Deputy of the Military Police, to lead 1,000 troops as reinforcements.

The battle commenced before the Chinese forces could fully set up their camp. The Burmese crossed the Pho Sam Ton River and attacked, scattering the Chinese forces. The reinforcement under Chaomuen Thip Sena, stationed at Wat Taleya, Phuen Niat, could not arrive in time. Seeing the Burmese killing the Chinese, the reinforcements also collapsed. Casualties among Thai and Chinese forces were high. Mangra seized the opportunity to advance and establish a camp at Phuen Niat, leaving Mang Khong Natha as the vanguard near Wat Sam Wihan. After this, there is no record of Thai forces engaging the Burmese further, presumably holding the capital and letting the Burmese act as they pleased.

Consideration

The battle at Pho Sam Ton represented a Thai attempt to set up an operational base and conduct raiding attacks to weaken the enemy and gather intelligence. However, the operation failed because the Burmese acted first, preventing the Thai forces from establishing themselves and executing the planned maneuvers.

The Burmese army under King Alaungpaya besieged Ayutthaya in April B.E. 2303, during the early reign of King Ekathat, who had no experience in warfare. He could only summon capable military officers to defend the capital and send generals who had been absent from battle for a long time to confront the enemy. As a result, they were unable to resist the Burmese forces and had to retreat to establish defensive positions within Ayutthaya. The Thai populace and officials petitioned to invite Prince Uthumphon, who had entered the monkhood, to take command of the Thai army, which subsequently improved the resistance.

The Attack on Ayutthaya (Ayutthaya, B.E. 2303)

On 23 April B.E. 2303, approximately 2,000 Burmese soldiers advanced to the rear moat on both sides (the “moat” refers to the river at the southern end of the city, near the mouth of Khlong Takhian). At that time, the merchant boats retreated from the northern side and gathered at the rear moat in large numbers. This included royal barges, ceremonial barges, and fleet vessels kept in the northern shipyard beside the palace. The Burmese slaughtered men, women, and children in great numbers and then burned all the boats at the rear moat.

แผนที่สังเขปการแสดงการรบที่โพธิ์สามต้น

(ภาพจากหนังสือการเสียกรุงศรีอยุธยา ครั้งที่ 2 พ.ศ.2310)

Use of Artillery

By 29 April B.E. 2303, the Burmese had positioned their artillery at Wat Ratchapli and Wat Kasat to the west, firing into the inner city. King Uthumphon rode his royal elephant to personally oversee the defense, ordering the gunners to return fire from the city’s forts. The exchange of fire continued until evening, when the Burmese withdrew. On 30 April B.E. 2303, the Burmese placed their artillery at Wat Na Phra Meru and Wat Hastadawas, bombarding the royal palace continuously day and night. Their cannonballs struck the apex of the Throne Hall of Suriya San Amarin, breaking it and causing it to collapse.

Artillery stationed in Mandalay

(Image from Burma at War with Thailand: Concerning the Wars Between Thailand and Burma)

On the day the Burmese fired upon the palace, King Alaungpaya personally commanded the operation and ignited the cannons himself. By chance, one of the cannons exploded, seriously wounding him and causing severe illness that day (from the article “Buddhism,” discussing the circumstances of King Alaungpaya’s death: … Alaungpaya, seeing that the flood season was approaching, sent a royal message into the city stating, “Being a supreme Bodhisattva, I wish to tour and inspect Ayutthaya…”).

To bestow auspiciousness upon the entire Thai nation, as the Supreme Buddha did when entering Kapilavastu, … Thailand replied that, “In this current eon, the Buddha has already appeared four times. Maitreya, the Bodhisattva, still resides in the Tusita Heaven. At present, it is still within the span of the teachings of the Buddha Sakyamuni, not yet reaching 5,000 rains. How could Thailand trust any pretender Bodhisattva who comes secretly, flaunting extraordinary human powers? We fear they would be burned in the great hell of Avici as a result of their grave offenses.”

King Alaungpaya, upon receiving that message, became extremely angered and personally fired a cannon. Too much gunpowder was loaded, causing the cannon to explode and injuring him, forcing the Burmese army to retreat. Alaungpaya passed away along the way (http://www.worldbuddhism.net/buddhism-history/Burma.html, 14/7/2547). The following day, 1 May 1760, the Burmese lifted the siege and moved northward, intending to exit via the Mae Lamao Pass. However, before leaving the Tak region, King Alaungpaya died en route at Mo Kalok, Tak Province (some Burmese sources report it was due to a large elephant abscess, an old illness; Chaow, 1985: 644).

The Burmese retreat was hurried and immediate, leaving no time for proper preparation. They could not transport the cannons and had to bury them in the royal camp. Later, the Thais recovered several dozen of these cannons. Initially, the Thais did not know that King Alaungpaya was gravely ill and assumed the Burmese withdrawal was a stratagem, so they did not pursue. When it became clear that the Burmese had truly lifted the siege, King Uthumphon ordered Phraya Yommarat and Phraya Siharatdechochai to lead forces in pursuit. They followed as far as Tak but could not catch the enemy. Even if they had, it would have been of little use, as the Burmese were already in retreat and returned without opposition.

Sequence of Events in the War, B.E. 2302–2303

Date | Month | B.E. | Event |

2302 | King Alaungpaya ordered Mangra to lead his army to attack the towns of Tenasserim and Mergui at the end of that year. King Alaungpaya sent his forces to invade Siam. | ||

11 | April | 2303 | The Burmese army advanced to Ayutthaya. |

23 | April | 2303 | Two thousand Burmese soldiers advanced to attack the rear moat on both sides. |

29 | April | 2303 | The Burmese brought cannons and positioned them at Wat Ratchaplee and Wat Kasatra, firing into the royal city. |

30 | April | 2303 | The Burmese positioned their cannons at Wat Na Phra Meru and Wat Hasdavas, firing toward the royal palace. King Alaungpaya personally supervised the ignition of the cannon, but it accidentally exploded, causing him severe injuries. |

Sketch map showing the attack on Ayutthaya in B.E. 2303

(from the book The Fall of Ayutthaya, the Second Time, B.E. 2310)

- 2. Preparation: King Alaungpaya’s hasty decision left little time for essential preparations, which in earlier times usually took the Burmese nearly a year to complete. Therefore, the major problems that Burma was likely facing at this moment could be as follows.

2.1 Manpower: The forces that attacked Tavoy and later advanced to Mergui and Tenasserim numbered only about 8,000 men, while the exact number of the main army is unknown. As for the two additional armies ordered to be assembled, their strength is also uncertain. The number might have been smaller than before due to the haste of mobilization, or perhaps larger since Burma had already secured several provinces by this time.

2.2 Force Composition: From previous operations, the following considerations may be noted:

-Naval Forces: The necessity of a fleet was to counter the Siamese navy, as Ayutthaya was surrounded by water, just as had been done in earlier campaigns.

-Artillery: The cannons used to bombard the royal city had to be of sufficient range, which the Burmese possessed and had already employed. These were likely brought along with the second wave of troops that followed later. However, during the battle, when the Burmese fired their cannons into the city, the Siamese retaliated relentlessly with their own artillery.

2.3 Logistics: In terms of logistics, especially food supplies, it is evident that the Burmese had made no preparations specifically for the attack on Ayutthaya. However, since Burma had been frequently engaged in warfare during that period, it is possible that some provisions had been stored in advance and were used temporarily. Historical records do not provide detailed information on these three matters, and they are therefore raised here merely as points of consideration worthy of note.

Artillery troops (B.E. 2422)

Picture showing a cannon mounted on an elephant’s back, an ancient combat technique dating back to the reign of King Bayinnaung

(from the book Burma’s Wars with Siam: On the Conflicts Between Thailand and Burma)

3. The Assault: Although the Burmese had not made prior preparations, neither had the Siamese. However, the Burmese held an advantage in that they were battle-hardened, having engaged in warfare frequently, which allowed them to act more swiftly and take the initiative. They seized the opportunity to launch operations first; thus, their actions were in the nature of an assault. When King Alaungpaya decided to invade Siam, his vanguard forces immediately advanced through the Singkhon Pass. They were not in the preparatory stage but were already on the offensive. The Burmese compensated for their lack of preparation by executing rapid assault operations.

Burmese infantry procession (B.E. 2422)

(from the book Burma’s Wars with Siam: On the Conflicts Between Thailand and Burma)

Burmese cavalry wielding throwing spears

(from the book Burma’s Wars with Siam: On the Conflicts Between Thailand and Burma)

4. Thai Intelligence Operations: Although the intelligence efforts of the Thai side caused confusion and mistakes, leading to troop fatigue and loss of time, the operations nevertheless resulted in clashes at Kaeng Tum near the mouth of the Tanintharyi River, and at Ao Wa Khao, where the vanguard forces engaged the enemy. The latter area, located north of Prachuap Khiri Khan Province, was narrow and critical, with a strip of flat terrain along the coast while the inland area was a continuous mountain range extending to the Banthat Range. The battle at Ratchaburi, a frontier town, can also be regarded as a delaying and defensive effort in accordance with pre-established plans. In truth, Thailand’s intelligence operations—both strategic and tactical—did not yield satisfactory results, largely because the Burmese launched a sudden assault. Nevertheless, the military units still managed to carry out defensive actions that corresponded, at least in part, to the broader plan for national defense, though under rather pressing circumstances.

- 5. Enemy Lines of Advance

5.1 Singkhon Pass: This was the route through which the enemy’s vanguard actually entered. It appears that when the decision was made, the Burmese troops stationed at Mergui were about 135 km from Ban Singkhon as the crow flies, so it was deemed prudent to conserve forces and use the nearer route. Even if this exposed the intent to invade, it was preferable to exhausting the troops by forcing them to march via the Three Pagodas Pass and endure hardship for five to six days. The period was short, and Thailand could hardly prepare much.

Three Pagodas Pass

(from the book Burma’s Wars with Siam: On the Conflicts Between Thailand and Burma)

5.2 Three Pagodas Pass: Although reports of the enemy’s presence were received even when none had yet appeared, the information was nonetheless plausible, as history records that two additional Burmese armies were to follow. While the exact details were not stated, it is presumed that they would have entered through this pass.

5.3 Mae Lamao Pass: It is uncertain how the authorities in Kamphaeng Phet obtained their strategic intelligence, but reports indicated that another Burmese army was to advance through this route. This caused confusion, leading to both loss of time and unnecessary expenditure of effort.

6.Thai Preparations: After the fall of Ratchaburi, King Uthumphon left the monkhood to organize the defense of the capital. Efforts were made to gather the populace, strengthen fortifications, and dispatch troops to delay the Burmese advance at Suphan Buri. Within a short time, battles took place at Thung Ta Lan and fiercely at Pho Sam Ton, before the Burmese finally reached Ayutthaya itself. King Uthumphon had very little time to make thorough preparations, and the delaying actions were carried out only to the extent possible under the circumstances.

Three Pagodas Pass

(from www.thaicabincrew.com/html/memory21.htm, 20 July 2004)

- 7. Burmese Operations: After the battle at Pho Sam Ton, the Burmese advanced to surround the capital, apparently concentrating their forces on the northern side rather than completely encircling the city, while also launching operations in other directions.

7.1 Deployment to attack the rear moat on both sides was likely intended to destroy Thai boats and prevent the transport of additional food supplies into the capital, thereby hastening the end of the conflict.

7.2 The Burmese bombarded the city with heavy cannon fire, to which the Thais responded. After several days, the Burmese continued their bombardment day and night, likely hoping to force a Thai surrender through continuous shelling rather than by starving them out, since their own provisions were limited and could not sustain a prolonged siege. However, an accident occurred when a cannon exploded and severely injured King Alaungpaya. The following morning, the Burmese forces withdrew, marking a complete failure of their campaign.

8. The Burmese reached Ayutthaya on 11 April B.E. 2303 and withdrew on 1 May B.E. 2303, remaining before the capital for a total of twenty days. They were unable to destroy the Siamese defenses, and the duration was not long enough to cause a shortage of provisions or force a surrender.

9. A final question worth considering is whether the Burmese would have withdrawn had King Alaungpaya not been severely wounded. In A History of South-East Asia, Volume I by D.G.E. Hall, page 562, the reasons for the withdrawal were summarized as follows:

“… King Alaungpaya invaded Siam and laid siege to Ayutthaya, claiming as his justification that the Siamese had refused to surrender the Mon rebels who had fled to seek refuge under Siam’s protection. In truth, however, Alaungpaya sought to restore Burma’s glory to the greatness it had achieved under King Bayinnaung. The Siamese asserted that even if Alaungpaya had not been severely wounded, he would still have had to withdraw because he was unprepared for a prolonged war. Therefore, he was compelled to decide to return before the rainy season of A.D. 1760. Nevertheless, his death only postponed Burma’s next invasion of Siam for another two or three years …”10. As for the Burmese retreat, it is regrettable that Siam did not pursue them, fearing it might be a Burmese ruse, and thus missed the opportunity. The Burmese withdrawal appeared hasty, suggesting they would have chosen the shortest route via the Three Pagodas Pass. However, since that route became difficult once past Kanchanaburi, the path through Tak and the Mae Lamao Pass was likely more favorable—still fertile and untouched by any previous movement during their advance. It was possible to obtain food supplies along the way. If the Burmese indeed took this route, as reason suggests, it would indicate that their army was already facing a shortage of provisions.

11. In this campaign, the Burmese acted without prior intent or preparation and advanced by a long and difficult route. Had they carried out the same operations but instead used the shorter route through the Three Pagodas Pass, their vanguard would have reached Ayutthaya much sooner. Both sides would have had even less time to prepare, but the smaller Burmese forces—being the aggressors and initiators—would have been ready first. It remains uncertain whether the standing forces of Siam at that time would have been sufficient to deal with the situation.

(Chanya Prachitromrun, 1993: 24–39)

According to evidence in the Thai Royal Chronicles, during the siege of Ayutthaya King Alaungpaya personally directed the firing of a cannon, which accidentally exploded, causing him severe injuries. As a result, he was forced to retreat northward, leaving subordinate commanders to cover the rear. When the Burmese forces reached the vicinity of Raheng (Tak), King Alaungmintayagyi passed away at the age of 46. Prince Mangra, his son, secretly sent word to the Crown Prince (Nongdokyi) and ordered that the news be kept from the army. Only a few commanders were informed. The Burmese returned with the royal remains through Hongsawadi and Yangon, where the cremation was held at Rattansingha. His ashes were then enshrined in a pagoda at Shwebo. (Chusiri Chamraman, 1984: 62)

However, the Hoke Kaew Chronicle records that during the five-day siege of the Siamese capital, King Alaungpaya became gravely ill with a large abscess at the nape of his neck (Chao Rouptewin, 1985: 644), forcing him to withdraw his army. He died at Mottama (Martaban) in May B.E. 2303 at the age of 45. Yet Burmese historian Maung Tin Aung later affirmed the Thai account. Moreover, the Burmese claim that King Alaungpaya invaded Ayutthaya because Siam had violated the Tavoy frontier does not align with Thai sources. According to A History of South-East Asia by Professor D.G.E. Hall, a neutral historian, the Hoke Kaew Chronicle tends to present Burmese–Siamese relations in favor of Burma. The book clearly states that King Alaungpaya sought “to invade Siam,” not that Siam provoked the conflict.

Nongdokyi, also known as Yaudokyi (Manglok), the eldest son, succeeded King Alaungmintayagyi. During his reign, the Prince of Taungoo rebelled, forcing Burma to spend time subduing the Mon and restoring order in Taungoo. Nongdokyi ruled for only three years (B.E. 2303–2306) before his death, after which Prince Mangra, his younger brother, ascended the throne as the third monarch of the Alaungpaya Dynasty. King Mangra was a highly skilled and powerful military leader, praised by the Burmese as the equal of King Bayinnaung—the Conqueror of Ten Directions who captured Ayutthaya in its first fall. King Mangra was deeply trusted and beloved by his father, having fought alongside him in campaigns since before the age of twenty, and had once commanded tens of thousands of troops in suppressing and subjugating the Mon territories in the south. (Chao Rouptewin, 1985: 648)

3.3 What were King Hsinbyushin’s (King Mangra’s) reasons for attacking Ayutthaya?

In 1763 (B.E. 2306), King Hsinbyushin (also known as King Mangra or Siridhammaraza), the second son of King Alaungpaya, ascended the throne after his elder brother, King Naungdawgyi (Manglok). He was a monarch who greatly favored warfare. King Hsinbyushin ascended the throne in December 1763.

The Burmese Battle Formation: “Wichaka Phayuha”

(Scorpion-Claw Formation)

*(Image from the book “Burma Fights Siam: On the Wars Between Thailand and Burma”)

While still awaiting his coronation ceremony, King Hsinbyushin had already devised plans to attack Ayutthaya. He appointed Aphaykhamani as Ne Myo Sithu Bodi (Nemyo Sihabodi) to govern Chiang Mai and to gather able-bodied men from the regions of Lanna and Lan Xang into an army with the objective of invading Ayutthaya. Nemyo Sihabodi departed from Rattasingha (the Burmese capital) in March 1763 with an initial force of 20,000 soldiers, 100 elephants, and 1,000 horses. Meanwhile, the king appointed another Burmese general named Mahanoratha (Mahanaratha) to lead an army of equal size to march toward Tavoy, Mergui, and Tenasserim, and then advance through Ratchaburi to attack Phetchaburi, Chaiya, Chumphon, Kanchanaburi, and Suphanburi. After capturing these cities, they were ordered to wait at Suphanburi for further instructions.

(The strategy of ordering the armies to advance from two directions in a pincer movement was devised by King Hsinbyushin of Ava nearly 200 years before Hitler employed the same tactic.)

(Khajorn Sukpanich, 2002: 263)

In 1764 (B.E. 2307), King Hsinbyushin led his army to attack Manipur and successfully captured it in December. The following year, he brought the local people back with his troops to Ava, which he established as the new capital. The king moved into the city in B.E. 2308 (1765). The city gates of Ava, which he had newly renovated, were named after various foreign cities: Chiang Mai, Mottama (Martaban), and Mogaung were the names of the eastern gates, while the southern gates were named Kaingma, Hanthawaddy (or Pegu), and Onyong (now Hsipaw).

The western gates of Ava were named Vientiane, Lan Xang, and Chiang Tung, while the northern gates were named Tanintharyi (Tenasserim) and Ayutthaya. The residential areas within the city were divided according to ethnicity — one section for Indian merchants, another for Chinese traders, a quarter for Christians, and another for captives taken from Siam (Ayutthaya) and Manipur. The royal palace was constructed like a fortified city, complete with walls, battlements, and moats. King Hsinbyushin (Mangra) pursued a policy of expanding his power and influence to build an empire comparable to that of King Bayinnaung, the great conqueror of Siam in the first Ayutthaya war. His ambition was clear — to conquer Ayutthaya. As recorded by Maung Tin Aung, “… the intention of King Hsinbyushin to subdue Ayutthaya was well known among the Siamese, who could not remain calm once they learned that he had ascended the Burmese throne …”

According to The King Taksin the Great (Old Palace Conservation Foundation, 2000: p. 32), the Burmese goal was to completely destroy Ayutthaya, as King Hsinbyushin believed that Ayutthaya’s interference in the Burmese vassal states — a legacy of the Alaungpaya Dynasty’s sphere of influence — was indirectly encouraging rebellions within the Burmese empire. Therefore, it became imperative to annihilate the Ayutthaya Kingdom, so it could no longer serve as a refuge or supporter of Burmese dependencies.

Furthermore, Wisetchaicharee (1998: p. 250), in Thai-Thai: The Fall of Ayutthaya, wrote that one reason for King Hsinbyushin’s invasion of Ayutthaya was that the Siamese failed to send tribute to King Alaungpaya as promised.

This evidence came from the letters of European missionaries residing in Ava and Rangoon during the reign of King Bodawpaya (1783–1806 CE), and it aligns with the Chronicles of the Konbaung Dynasty, which state that when King Alaungpaya besieged Ayutthaya, the Siamese deliberately delayed in order to take advantage of the monsoon floods by sending envoys to the Burmese army pretending to surrender and offer tribute, thus buying time for the seasonal waters to hinder the Burmese advance.

King Alaungpaya, seeing that the season of northern floods was approaching and being afflicted by illness, was compelled to withdraw his troops. King Hsinbyushin (Mangra) was well aware of this event, for it had occurred during the final campaign of his father, whose forces had to retreat from Ayutthaya due to both Thai stratagems and natural obstacles. These factors greatly benefited Ayutthaya, making it appear as though Burma had been defeated, since the Burmese were forced to abandon the siege without success. Moreover, King Alaungpaya himself passed away from illness during this campaign. This incident became a decisive factor that strengthened King Hsinbyushin’s determination to conquer Ayutthaya once and for all so that he might become a universal emperor — a concept deeply rooted in Burmese political culture. Therefore, King Hsinbyushin’s decision to send an army to attack Ayutthaya did not stem from perceiving Siam as weak. From the Burmese perspective, late Ayutthaya was by no means fragile; it remained a formidable capital worthy of its name in every respect.

Another reason the Burmese invaded Siam in 1764 (B.E. 2307) was that, during King Hsinbyushin’s reign, the towns of Mergui (Marid) and Tenasserim (Tanintharyi) were under Siamese control, while Tavoy (Dawei) belonged to Burma. When the Burmese throne changed hands between Manglon and Mangra, Huitongja, the governor of Tavoy, rebelled, killing the Burmese officers stationed there and sending tribute to Ayutthaya. The Burmese then sent an army to suppress Tavoy. When the town fell, Huitongja fled with his family toward Mergui. The Burmese troops pursued him through the Singkhon Pass (in present-day Prachuap Khiri Khan Province) and took the opportunity to attack Khamnoet Nopakhun (Bang Saphan District), Khlong Wan, Kui Buri, and Pran towns. However, when they reached Phetchaburi, they encountered the Siamese forces led by Phra Ya Tak (later King Taksin) and Phra Ya Phiphatkosa, who were awaiting them. The Burmese army was repelled and forced to retreat back through the Singkhon Pass.At that time, the governor of Kamphaeng Phet had passed away, and King Ekkathat therefore appointed Phra Ya Tak to be Phra Ya Wachiraprakan, the new governor of Kamphaeng Phet, though he was ordered to continue serving in Ayutthaya for the time being. The Burmese force that invaded the southern provinces on this occasion was merely a raiding party. Upon encountering the Ayutthaya army that had been sent to intercept them, they fled in retreat.

Wisetchaisri (1998: p. 249) wrote that “…the Burmese invasion of Siam through the Singkhon Pass was a new route, first used during the reign of King Alaungpaya in his campaign against Ayutthaya. During King Alaungpaya’s reign, Burma possessed a naval force capable of transporting troops swiftly from Rangoon (Yangon) and Martaban (Mottama) down to Tavoy. King Alaungpaya intended to use this new route, which the Siamese would not anticipate, to launch a rapid assault. Formerly, the Burmese had only two customary invasion routes into Ayutthaya: from the north — through Chiang Mai, or via Tak and Raheng (Mae Sot) through the Mae Lamao Pass — and from the west, entering through the Three Pagodas Pass.”

3.4 Which two Burmese generals during the reign of King Hsinbyushin led the invasion of Siam, and how did they advance their armies?

In 1765, King Hsinbyushin of Burma sent two great generals, Maha Nawrahta and Ne Myo Thihapate, to lead the invasion along two routes, the northern and the southern, as recorded in the Konbaung Chronicle as follows.

- Preparation for the Burmese Army (Konbaung) (Burma, 1764)

According to the Konbaung Chronicle, King Hsinbyushin had long ordered preparations for the invasion of Ayutthaya. Initially, he commanded that 27 military divisions be organized, consisting of 100 elephants, 1,000 horses, and 20,000 soldiers.

- General Ne Myo Thihapate

Deputy generals: Kyawdin Thihgathu and Tuyin Yamagyaw

Movement: The entire force departed from Ava in March 1764.

Mission: To suppress the rebellion in Lan Na, attack Lan Chang, and then advance directly toward Ayutthaya.

After Ne Myo Thihapate gathered troops from various towns in the Shan States, suppressed the Lan Na rebellion, and captured Luang Prabang, his forces increased to a total of 40,000 men (according to the testimony of the people of Ava, 5,000 men) (Sunait Chutintaranond, 1998: 22).

King Hsinbyushin, perceiving that Ne Myo Thihapate’s army advancing alone through Chiang Mai would not be sufficient to conquer Ayutthaya, therefore organized another army consisting of 100 elephants, 1,000 horses, and 20,000 soldiers.

- General Maha Nawrahta

Deputy generals: Neimyou Gunaye and Tuyin Yanaungyaw

Movement: The army advanced to join additional forces conscripted from Hongsawadi, Martaban, Tenasserim, Mergui, and Tavoy, forming a total strength of 30,000 men. The entire force departed from Tavoy on September 25, 1765.

Mission: To attack the targets of Phetchaburi, Ratchaburi, Suphanburi, Kanchanaburi, Sai Yok, and Sawanpong before advancing toward Ayutthaya.

Considerations

According to Burmese records, King Hsinbyushin had long prepared to attack Ayutthaya, but the Thai side had no knowledge of this. Even merchants traveling back and forth were unaware. Upon examination, our intelligence may have been somewhat weak, but considering the actual conditions at the time, it was possible to know that the Burmese were preparing their army, though it was impossible to know whom they intended to fight, as Burma was constantly engaged in conflicts. Moreover, Ne Myo Thihapate’s army, once organized, first carried out operations in Lan Na and Lan Chang before advancing toward Ayutthaya, which likely explains why the Thai side remained unaware. The movement began in March 1764.

Maha Nawrahta’s army departed on September 25, 1765, because this army traveled a shorter distance and had all its targets located within Siam.

Both armies recruited additional troops as they fought, increasing their strength. By the time they advanced to besiege Ayutthaya, the Burmese forces totaled 80,000 men (Sunait Chutintaranond, 1998: 18).

Burmese troop organization

(Image from the book The Fall of Ayutthaya, Second Time, 1767)

North | Organization of the Burmese Army | West |

Ne Myo Thihapate | GeneralDeputy generalsElephants | Maha Nawrahta |

The entire force departed from Ava. | Movement | Advanced to join additional forces conscripted from Hongsawadi, Martaban, Tenasserim, Mergui, and Tavoy, totaling 30,000 men. |

Departed from Ava in March 1764 | Movement schedule | Departed from Tavoy on September 25, 1765 |

The two armies began their movements six months apart due to differing missions and distances, with the plan for them to coordinate and arrive at their destination simultaneously.

Considerations

1. Causes of the war

– According to Burmese records, King Hsinbyushin had long ordered preparations to attack Ayutthaya.

– According to Thai sources, no other reason is recorded except that Burma perceived Siam to be weak.

– The causes from both sides are consistent: Burma wanted to attack Siam, and Siam was weak; therefore, Burma launched the invasion.

2. The operations of the Burmese army in this campaign were essentially looting, which was almost typical of warfare at the time, where small units sometimes acted independently and committed abuses. However, it is unlikely that such acts were directly ordered by high-ranking commanders. In this instance, both armies conducted operations that can be described as looting, with each force acting separately at different times. The English term “raid” is also used to describe these actions. Therefore, it can be concluded that the army’s operations were indeed acts of plundering, as confirmed by both Thai and foreign sources.

The Burmese army’s actions were likely severe and were probably sanctioned and fully understood by King Hsinbyushin, who, being fond of warfare, nevertheless did not personally participate in this campaign as an honorific presence. It is difficult to interpret the situation otherwise.

Movement: The army advanced toward Ayutthaya. Initially, the Burmese intended only to loot Thai towns (or conduct quick raids, which were normally small-scale operations involving a rapid incursion into enemy territory to gather intelligence, create disorder, or carry out destructive actions before withdrawing). Each army took what it could, and both operated independently. However, Siam’s weakness encouraged the Burmese, leading both armies to advance all the way to Ayutthaya. This operation was poorly conducted, which is why King Hsinbyushin did not lead the campaign personally.

The Burmese chronicles state that the reason King Hsinbyushin did not personally lead the attack on Ayutthaya was initially due to minor border disputes between Burma and China. A Chinese merchant bringing goods to Baan Mo in the Tai Yai region had his merchandise stolen by Burmese officials. When he complained to the local authorities, he received no redress, prompting him to report the matter to Chinese officials in Yunnan. Another Chinese merchant bringing goods to Chiang Tung was similarly defrauded by Burmese officials, leading to a dispute in which one Chinese person was killed. This incident was reported to Yunnan authorities, and the exiled Tai Yai princes in Yunnan escalated the matter. The Yunnan officials then submitted the issue to Emperor Qianlong, who ordered a military response against Chiang Tung as retribution for the death of the Chinese.

From Ava, Ahsa Wun Gyi (Wun Chyi Maha Thihasura) was sent to lead 20,000 troops to repel the Chinese beginning in October 1766. In reality, Ahsa Wun Gyi’s army was the second expedition, as the first had been unsuccessful. This coincided with the period when the Burmese were besieging Ayutthaya and remaining in place during the rainy season instead of retreating as in previous campaigns.

The Chinese sent armies to fight the Burmese on four occasions. In the first two campaigns, the Chinese were forced to retreat. During the third campaign, the Chinese sent a large force to invade Burmese territory in December 1767, which coincided with events in Siam: Ayutthaya fell in April 1767, and in October–November 1767, King Taksin defeated the Burmese at Pho Sam Ton Camp. The third and fourth Chinese expeditions involved massive numbers of troops. In the fourth campaign, Ahsa Wun Gyi had to exert great effort to cut off and encircle the Chinese army, forcing the Chinese commanders to send negotiators to seek peace. The Burmese agreed to compromise, allowing the Chinese troops and their weaponry to withdraw safely from Burmese territory. Thus, the war between China and Burma came to an end (Kachon Sukpanich, 2002: 265–271).

The Thai side thus interpreted the initial stage of warfare as involving raiding and looting various towns, in accordance with Burmese military practice. Some of the items looted by the Burmese remain in Burma to this day. The Burmese likely did not regard this as a disgrace but possibly as possessions legitimately obtained through warfare.

3. We have already learned that King Alaungpaya’s bold actions involved invading Siam. Now it is necessary to consider the succeeding generation.

Before ascending the throne, King Hsinbyushin, according to the royal letter edition of the chronicles, stated: “Because I did not approve of my brother ascending the Burmese throne, I desired to become king myself, with a firm resolve to capture the city of Ayutthaya.”

Upon his accession, he employed his strategy to extend his power and create an empire akin to that of King Bayinnaung. It was recorded: “Hsinbyushin’s objective to subjugate Ayutthaya was well known to the Thai people, who could not remain calm upon learning of his accession to the Burmese throne.”

Considering this, the Burmese intention to attack Ayutthaya did not emerge only during King Alaungpaya’s reign and later under King Hsinbyushin. It was a continuous ambition passed from father to son over two generations. History thus repeated itself (Chanya Prachitromron, 1993: 50–57). Professor Rong Sayamanon (1984: 40) analyzed this continuity as follows.

“…The Hokkaew Chronicle extensively narrates events concerning King Hsinbyushin, describing in great detail the organization of the army to attack Ayutthaya, filling as much as 40 pages. However, it can be summarized as Sir Arthur Fair wrote: Hsinbyushin inherited royal authority and military skill from his father, Alaungpaya. Shortly after ascending the throne, he prepared to attack Ayutthaya to avenge Alaungpaya, who had been scorned by the Siamese, by increasing the forces of Ne Myo Thihapate by 20,000 men. Ne Myo Thihapate was appointed the supreme commander of the northern army. In the royal letter edition of the chronicles, Ne Myo Thihapate is referred to as Posuphla (Sang Phatnothai, n.d.: 130).

3.5 How did Ne Myo Thihapate, the supreme commander of the Burmese northern army, conduct his operations?

Ne Myo Thihapate reached Chiang Mai and completely subdued the region. Chiang Mai submitted to his command, and to prevent any threat from the rear, he proceeded to attack Lan Chang. The king of Lan Chang, who personally led his forces, was decisively defeated and agreed to become a vassal state of Burma. Afterwards, the Burmese commander took control of the Tai Yai territories, ordering the preparation of arms for the army. By mid-August of that year, Ne Myo Thihapate’s forces had grown to 40,000 men, mostly Tai Yai, and he advanced southward toward Tak as his first target.

At Tak, the governor, seeing the enemy’s superior strength, defended the city. The Burmese troops fought valiantly and captured Tak in a short period. They then moved to Rahang, which fell easily as the local ruler submitted. Kamphaeng Phet was another city that the Burmese seized with little resistance. Next, they advanced along the Yom River to attack Sawankhalok. The governor of Sawankhalok had prepared a strong defense, requiring the Burmese to engage in significant combat before capturing the city. Afterwards, they proceeded to Sukhothai, whose ruler submitted peacefully, and then continued to Phitsanulok. Phitsanulok had strong fortifications and did not yield easily, forcing the Burmese to use military force to take the city.

Organization of Ne Myo Thihapate’s Army

———————–

Land forces

Naval forces

———————–

Rear guard (reserves)

Number of units

Elephants

Horses

Soldiers

General

10 (9 conscripted units, 1 under direct Burmese command)

100

300

8,000

Sirirajatachan

15 (14 conscripted units, 1 directly commanded by Burma)

200

700

12,000

Tadomengteng

20

300 ships

Tuyin Yamagyaw

13

Ne Myo Thihapate

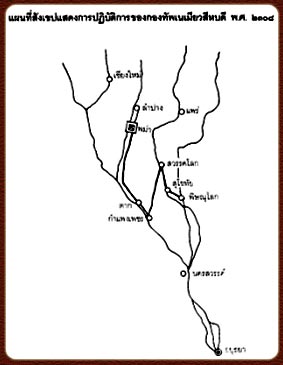

A total of 58 units, 300 elephants, 1,000 horses, and 43,000 soldiers moved out from Lampang in September 1765, with the first targets being Tak and Phitsanulok.

Reorganization:

Ne Myo Thihapate stopped at Phitsanulok for 10 days to reinforce elephants, horses, and troops before continuing operations.

Reorganization of Forces: After capturing Phitsanulok, Ne Myo Thihapate reorganized his forces into two groups, each consisting of 10 units under the command of Sirirajatachan and Jokongjodu. Both groups were tasked to advance south toward Nakhon Sawan and Ang Thong, while Ne Myo Thihapate remained at Phitsanulok as the command center. The local Thai rulers did not resist and willingly provided elephants, horses, and military supplies to the Burmese. Commanders of the two groups also sent the local rulers and their families to Ne Myo Thihapate at Phitsanulok.

(Image from the book The Fall of Ayutthaya, Second Time, 1767)

Considerations

From the northern direction, Ne Myo Thihapate’s army advanced from Lampang to subdue the northern towns. Among six northern towns, three resisted while three submitted. The towns that resisted were Tak, Sawankhalok, Kamphaeng Phet, and Phitsanulok, while those that submitted were Rahang, Kamphaeng Phet, and Sukhothai, resulting in an overall balance between resistance and submission. Afterwards, Ne Myo Thihapate organized two forward guard units to continue operations southward toward Nakhon Sawan and Ang Thong.

The Thai towns were believed to have already contributed large numbers of men to service in the capital. The Thai forces from these towns attempted to resist but were unable to withstand the Burmese and suffered a crushing defeat. Ne Myo Thihapate continued his advance along the river, gathering supplies and destroying some Thai villages along the way, primarily to intimidate the Thai and prevent them from following the Burmese army. However, the Thai were already incapable of uniting against the Burmese, as they had not prepared for warfare following the Alaungmintaya campaign. Even though the Burmese intermittently refrained from attacking for five years, they advanced from the north and established positions to the east of Ayutthaya around January 20, 1766, near Pak Nam Prasop, approximately two kilometers from the capital.

3.6 กองทัพพม่าฝ่ายใต้ของมังมหานรธา ปฏิบัติการอย่างไรบ้าง ?

Maha Nawrahta’s army, serving as the supreme commander of the southern army, numbered 20,000 men. They moved from Martaban to Tavoy and remained there until the end of the rainy season in 1765. Afterwards, they advanced through Mergui, crossed the Tenasserim Hills, and attacked Kanchanaburi and Suphanburi. They then passed along the Thai coastal towns of Kui, Pran, Phetchaburi, and Ratchaburi before turning north toward Ayutthaya, taking less time than during King Alaungpaya’s campaign. Along the way, they paused to gather supplies. At Phetchaburi, a Thai force attempted to resist, but it was too small to be effective.

Battle at Phetchaburi: The governor, knowing the Burmese army was large, prepared to defend the city. When the Burmese arrived, they divided their forces into two groups: one scaled the walls with ladders, while the other dug at the foundations. The Burmese captured the city in a short time. Once inside, looting was conducted—any soldier who seized goods kept them, while weapons and military equipment went to the Burmese commanders. The same procedure was followed in every city that resisted. After securing a city, the local ruler and officials were required to swear allegiance and establish garrisons before the army moved on to Ratchaburi.

When the governor of Ratchaburi learned that Phetchaburi had fallen, he submitted peacefully. The Burmese had him and his officials swear allegiance according to protocol, then proceeded to attack Suphanburi. The governor of Suphanburi also submitted, allowing the Burmese to take the city with ease.

From Suphanburi, the Burmese turned west to attack Kanchanaburi, a well-fortified city with strong arms and supplies. The governor defended the city, but it could not withstand the larger Burmese force and eventually fell. The army then advanced to Sai Yok and subsequently captured two other towns, Sawampong and Saleng, whose exact locations in Thailand are unclear.

After capturing these seven towns, the Burmese organized seven units from each of the conquered towns. Mengji Kama-Nisan-da led the vanguard, while Maha Nawrahta commanded the main army, totaling 57 units advancing toward Ayutthaya (Chanya Prachitromron, 1993: 76–81). The Burmese fought fiercely against the Thai army, which was defeated. By January 1765, Maha Nawrahta’s army had established positions northeast of Ayutthaya, outside the island city near Thung Phu Khao, no more than three kilometers from Ayutthaya. The two Burmese armies maintained effective coordination.

Note

1. Pol. Lt. Col. Pisal Senawes (1972: 311) explained that “Maha Nawrahta” was the title of a Burmese official, not a personal name. The book Thai Battles the Burmese by Somdet Krom Phraya Damrong Rajanuphap stated that this Maha Nawrahta was personally named Manglasiri. The book also explained that “Ne Myo Thihapate” was a Burmese official title for the commander who captured Ayutthaya, but did not mention his personal name. Khajorn Sukpanich (2002: 263) noted that Ne Myo Thihapate’s original name was Aphayakamini.

The book Interesting Facts about Thonburi by the Foundation for the Conservation of Ancient Monuments in the Old Palace (2000: 147) explains that Ne Myo Thihapate held the title Posuphla, a Burmese military rank. This title appears in the Burmese chronicles during the capture of Ayutthaya in 1767 (Burmese records refer to him as Ne Myo Thihapate) and again in 1771, when Chao Suriyawong, the ruler of Luang Prabang, quarreled with Chao Siribunsan, the ruler of Vientiane. Chao Siribunsan requested King Hsinbyushin to send an army for support. King Hsinbyushin assigned Chikchingbo to lead the vanguard and Posuphla as the commanding general to assist Vientiane. Posuphla led the army to attack Luang Prabang, where Chao Suriyawong, unable to resist, submitted. Afterwards, King Hsinbyushin ordered Posuphla to establish a base at Chiang Mai to guard against the Thai army. Later, in 1773, Posuphla led an army to attack Phichai, after Chikchingbo had previously attempted but failed. In that campaign, Posuphla was defeated by Chao Phraya Surasi, and Phichai also returned.

- 2. Burmese Invasion Routes: When the Burmese advanced to attack Thailand, they typically entered through four main routes:

1) Through Chiang Mai

2) Through the Mae Lamao Pass, Tak Province

3) Through Phra Chedi Sam Ong, Kanchanaburi Province

4) Through the Singkhon Pass, Prachuap Khiri Khan Province (Pol. Lt. Col. Pisal Senawes, 1972: 321)