King Taksin the Great

Chapter 15: Royal Activities in the Promotion of Diplomatic Relations and Trade with China

15.1 What were foreign relations like during the Thonburi period?

In the Thonburi period, foreign relations took two forms: contact arising from ongoing warfare, and contact resulting from trade with the countries involved, namely:

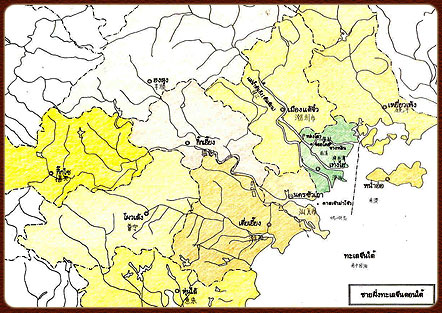

1. Relations with Burma Throughout the Thonburi period, relations between Siam and Burma were defined by continual conflict, as the two kingdoms remained at war almost without interruption, amounting to nearly ten major encounters. Examples include the battle with the Burmese at Bang Kung in Samut Songkhram in 1767, the Burmese attack on Sawankhalok in 1770, the first Siamese assault on Chiang Mai in 1771, the first and second Burmese attacks on Phichai in 1772 and 1773, the second Siamese assault on Chiang Mai in 1774, the Siamese-Burmese clash at Bang Kaeo in Ratchaburi in 1775, the campaign of Azaewunki into the northern towns in 1775, and the Burmese attack on Chiang Mai in 1776.

2. Relations with the Khmer Cambodia had long been a vassal of Siam since the Ayutthaya period until the fall of Ayutthaya to Burma in 1767, after which Cambodia became independent. During the Thonburi period, Cambodia was beset by internal conflict, dividing into two factions, one continuing in allegiance to Siam, the other turning toward Vietnam. This situation compelled Siam to send armies to suppress the Khmer on several occasions.

3. Relations with Lanna King Taksin the Great observed that whenever Burma launched an invasion of Siam, it consistently used Lanna as a military base and a storehouse of provisions. He therefore led an expedition against Chiang Mai and succeeded in driving out the Burmese in 1774. Thereafter Lanna was freed from Burmese control, with forces from Thonburi sent to provide protection.

4. Relations with the Malay towns The Malay towns comprised Pattani, Saiburi, Kelantan, and Trengganu, all of which had been vassals of Siam throughout the Ayutthaya period. After the fall of Ayutthaya, these towns declared independence. In the early Thonburi period, Pattani and Saiburi still retained allegiance to Siam, but by the later years they withdrew. King Taksin the Great allowed them to go, as the kingdom lacked the strength to send forces to subdue them.

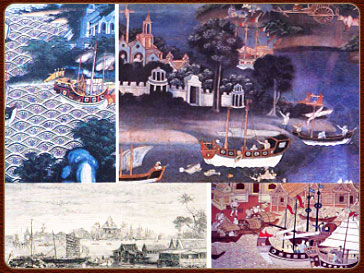

5. Relations with China During the Thonburi period, Chinese merchant junks regularly came to trade. Goods brought by Chinese merchants included weapons obtained from Western nations, rice, and various household items. King Taksin the Great took great interest in this commerce and therefore dispatched royal junks to trade with China as well, and also sent envoys to establish diplomatic relations on two occasions.

6. Contact with Western nations In the Thonburi period, there was contact with several Western countries, though the relations were not as close as in the Ayutthaya period, because the Thonburi era was relatively short. Westerners who came into contact with Thonburi included the Dutch, the English, the French, and the Portuguese (53 Thai Kings, 2000: 245-546) (see further details on Burma, Cambodia, Lanna, and the Malay towns in Chapter 10).

15.2 What was the relationship between Thailand and China like in the past?

The connection between the Thai people in the Southeast Asian peninsula and people of Chinese descent is clearly evidenced from as early as the Sukhothai period, or possibly earlier. Chinese from the mainland possessed great skill in navigating junks in search of trading locations rich in essential raw materials and resources throughout regions bordering the Pacific Ocean, including the area of the Gulf of Siam after earlier establishing trade along the Malay coast.

According to research by William G. Skinner in the study Les Sonques des Chinois du Siam, the earliest arrival of Chinese in what is now Thailand was likely in the early Sukhothai period. They traveled to trade by junk each year during the northeast monsoon, following the line of the Malay Peninsula from its southern tip along the eastern coast near present-day Nakhon Si Thammarat, Surat Thani, and as far north as Chumphon. When the southwest monsoon arrived, these Chinese merchants would purchase local products such as forest goods, teakwood, silk, satin, and glazed ceramics from the Thai lands.

King Ramkhamhaeng the Great

(Image from 203.144.136.10/…/ nation/pastevent/past_ayu.htm)

Whether earlier or later, it demonstrates the long-standing origin of the relationship between these two nations and ethnicities in the past. Official relations seem to have become clearly evident during the reign of King Ramkhamhaeng, when Chinese delegations were sent to Thailand around 1282 to 1293 several times. Finally, in 1296, King Ramkhamhaeng sent a delegation to reciprocate and establish diplomatic relations, marking the first official interaction during that period.

During the Ayutthaya period, relations between Thailand and China seemed to have lapsed for a time due to internal problems in China, including civil wars and the transition of power to the Ming Dynasty. Diplomatic missions began to be sent again, and commercial trade between the two countries expanded widely during the reign of King Songtham, around 1620–1632. Chinese merchants from the mainland were well supported and patronized by Thai officials and nobles (Siam Araya, 1(7): March 1993: 43).

During the more than 270 years of the Ming Dynasty, China sent diplomatic missions to Ayutthaya 19 times. Ayutthaya, in turn, sent royal missions bearing tribute to the Chinese emperor every three years, totaling 110 occasions. The personal goods that accompanied the tribute were also exempted from customs duties by the Ming government (Pimpaip Phisankul, 1998: 50).

15.2.1 How were diplomatic relations between Thailand and China during the Thonburi period?

According to the Chinese chronicles regarding Siam, translated by Luang Chen Chin Akson (Sutjai), an officer at the Vajirayan Library, from three Chinese books: the Kim Tia Chok Tong, Huang Qiang Bun Xian Meng Ke, and Yi Zab Si Su, presented to King Chulalongkorn. These three Chinese texts were official books commissioned by the Chinese emperor of the Qing Dynasty to have officials compile historical records of foreign countries that had maintained relations with China, including Siam. They indicate that Thailand and China had diplomatic relations from the Sukhothai, Ayutthaya, and Thonburi periods. Extracting the relevant passages concerning Thonburi, the following is recorded:

“During the Thonburi period, in the 46th year of Emperor Qianlong (third month of the year 1143 in the Chula Sakarat calendar), King Taksin of Siam (called ‘Jiang’ in Chinese records) appointed Long Pi Chai Sani (Luang Phichai Thani or Phet Prani) and He Ke Bu Tud (two vice-envoys) as royal envoys to present tribute. They reported that after being ravaged by the Mien Hui (Burmese invaders) and regaining territory through retaliation, the royal lineage of the previous ruler had been extinguished. The nobles united to elevate Taksin as the sovereign and sent local products as tribute according to custom. The senior officials reported to Emperor Gao Zhong Sun Hong Tai that King Taksin had dispatched envoys across the sea, showing respect and reverence. The officials then wrote a response following the original message. Emperor Gao Zhong Sun Hong Tai, recognizing that the journey from Siam required crossing high mountains and wide seas, hosted the envoys for two days.

On the route to deliver the tribute, Siamese envoys passed through Guang Dong Ma Ke Si (Beijing). Siam is located to the west of Guang Dong; the journey by sea took forty-five days and nights to reach the river at He Xiang Shuo Gui, Guang Dong province. They set the compass southward, followed the wind, and sailed northward through the Chinese sea for ten days and nights to the An Lam Sea (Vietnam). Along the way, they passed Mount Wu Luo, traveled another eight days and nights to reach the sea of Chiem Sam, and another twelve nights to reach the great Kunlun mountain, where they adjusted their course east-northeast and traveled five days and nights to the Chi Guang River in China, and five more days to the river mouth. They sailed two hundred li upriver to freshwater, then another five days to Siam Lo Xie (the city).

Siam Lo Xie had a major mountain to the southwest. Rivers from the southern mountains flowed into the sea. Cities along the route included Songkla (Songkhla), Sek Kia (Chaiya), Luk Kun (Nakhon Si Thammarat), and Tai Ni (Tani). According to the compiler of Bun Xian Tong Ke:

We examined the records of Siam Lo Xie, continuing from the Sui and Tang Dynasties, when it was called Xie Tou Guo. During Emperor Sui’s reign in the year Id Tiu (1148 BE, 33 years before Chula Sakarat), under the second ruler of the Sui Dynasty, Xie Tou Guo’s ruler was named Tai Yiep. Official Sun Chang Zhu Si noted that the ruler of Xie Tou Guo observed Buddhism, and the lineage of the ruler possibly shared the same surname as Buddha.

Examining the historical records of Siamese envoys, it appears that the people of Siam Lo Xie had no surnames. Whether they did or did not is uncertain due to a thousand-year gap, but the inhabitants were of Hulao (original Thai) descent. Chinese texts about various southern coastal countries praised Hulao women, calling the ruler Siu Hia, and commending her intelligence above men, indicating a continued cultural tradition.

Siam Lo Xie maintained relations with Tonghua (China) since the Yuan and Ming Dynasties. Under the Qing Dynasty, it extended and instructed envoys to bring rice to sell, benefiting the people in the territory. Previous officials of the Ming Dynasty collecting special products from coastal countries found them of little use, unlike the propriety of Siam Lo Xie.

But the ruler of Siam Lo Xie governed skillfully and honestly, unmatched, situated between various southern countries and An Lam Guo (Vietnam).” (Fine Arts Department, 1990: 43-45, 69-70)

After Ayutthaya had been defeated by the Burmese, Chen Chao (King Taksin the Great) gathered the remaining people and attacked the Burmese until they were driven back. He then attempted to restore the nation, and the people appealed to him to assume the throne as king. Chen Chao prepared to establish diplomatic relations with China in order to obtain imperial permission from the Emperor of China to send tribute, for if the Emperor recognized him, his political status would become more secure as a king accepted by neighboring states. Chen Chao therefore sent envoys to China to request permission to send tribute. The relations between King Taksin the Great and the Qing Dynasty may be divided into three phases, according to time and the development of events.

1. 1767-1770

The Qing Dynasty refused recognition because, during that period, China relied mainly on distorted reports from Mo Silin of Phutthaimat and thus would not acknowledge Thonburi. Moreover, during the first three years of the reign of King Taksin of Thonburi, China was engaged in warfare with Burma.

Qianlong Emperor (1736-1799)

(from the image www.chinapage.org/ dragon1.html )

2. 1770-1771

The Qing court began to sense the background behind Mo Silin’s distorted reports and gradually lost confidence in them. Therefore, the Qing court started to change its attitude and adopt a friendlier stance toward King Taksin.

3. 1771-1782

The Qing court granted official recognition to King Taksin and even offered special support (Muang Boran Foundation, 2000: 93-94). King Taksin the Great began to apply the idea that “the enemy of one’s enemy is a friend” in opening channels of contact with the Qing court. Whenever he captured enemies who were adversaries of the Chinese government, or when he obtained Chinese soldiers who had been prisoners of the Burmese in warfare, the King of Thonburi would always send them back to Guangdong to demonstrate his sincerity in establishing relations with China. The Qing Dynasty records state that the return of Chinese nationals occurred four times, namely:

– In 1772 (2015 BE), Zhuang Junqing and his group were sent back to their homeland

– In 1775 (2318 BE), nineteen Yunnan soldiers who had been Burmese prisoners of war were returned

– In 1776 (2319 BE), three Yunnan merchants were sent back to their homeland

– In 1777 (2320 BE), Ai Ke and six others, who were Burmese prisoners, were escorted and delivered to Guangdong, and thus an atmosphere of friendliness with the Qing court gradually emerged (Phimpraphai Phisansakul, 1998: 189)

a. King Taksin sent envoys to China how many times?

There is an article by Professor Chu Wenjiao, who studied relations between Burma and China, in which he stated that Chen Chao sent envoys to China twice, the first in the 36th year of the reign of the Qianlong Emperor and the second in the 46th year of the reign of the Qianlong Emperor, corresponding to 1771 and 1781 respectively. Professor Chen Jinghe wrote an article titled Several Problems Regarding the King of Thai, which is also about Chen Chao. In this article it is stated that from the 33rd to the 46th year of the reign of the Qianlong Emperor, Chen Chao sent envoys to China a total of eight times.

– 1768, the first mission in the 33rd year of the reign of the Qianlong Emperor; the envoy was Chen Mei

– 1771, the second mission in the 36th year of the reign of the Qianlong Emperor; this year was also the period when Siam sent Burmese prisoners to China

– 1772, the third mission in the 37th year of the reign of the Qianlong Emperor; Siam sent Chinese people from Haifeng, including one named Chen Junqing, to China

– 1774, the fourth mission in the 39th year of the reign of the Qianlong Emperor; this mission was to request the purchase of iron and sulfur

– 1775, the fifth mission in the 40th year of the reign of the Qianlong Emperor; Siam requested the Chinese merchant Chen Wanshen to deliver the royal letter to China

– 1776, the sixth mission in the 41st year of the reign of the Qianlong Emperor; this was the time when the merchant Mo Guangyi was asked to deliver the royal letter to the Emperor of China

– 1777, the seventh mission in the 42nd year of the reign of the Qianlong Emperor; Chen Chao sent envoys along with Burmese prisoners to Guangdong

– 1781, the eighth mission in the 46th year of the reign of the Qianlong Emperor; Chen Chao sent envoys to the court of the Emperor of China (sent twice)

Natthaphat Chantrawit (1980: 49-72) discussed relations between Thailand and China in the late Ayutthaya period in the article “Some Facts Concerning Late Ayutthaya and Thonburi History from Chinese Records,” stating that

“In the Chinese view, relations between China and Siam were similar to those China had with Korea and Vietnam, and that China and Siam came from the same origin, with Siam being a branch of China as well.”

According to the history of Siam as known to China, Xian Luo Guo was originally divided into two countries, “Lo-Suo” (Lo-Tsho, or the Kingdom of Lavo) and “Sichuan” (Hsuan, or the Kingdom of Sukhothai). Lo-Suo prospered under Khmer power. In the second year of the reign of Emperor Cheng-Ho of the Song Dynasty, 1114, Lo-Suo first established relations with China. As for Sichuan, it waged war against Lo-Suo and began relations with China in the fifth year of the reign of Emperor Pao Yao, 1257. By the late Yuan Dynasty, China had sent envoys to Sichuan three times, and Sichuan had sent envoys to China nine times, while Lo-Suo sent envoys five times. In the tenth year of the reign of Emperor Chih chen, 1350, King U Thong founded the Ayutthaya Kingdom and proclaimed himself the first King Ramathibodi.

In the tenth year of the reign of Emperor Hung-Wu of the Ming Dynasty, 1377, the king of Lo-Suo was named “Chan Diapeya” (King Borommarachathirat I, or Khun Luang Pa-Ngua). He waged war against Sichuan and won. In September 1377, this king sent his son to China bearing elephants, timber, and gold as tribute to King U Thong, or Emperor Ming Tai Hsu (who reigned from 1368 to 1399). Emperor Ming Tai Hsu bestowed a seal engraved with the title “Xian Luo Guo Wang Shi Yin” upon the prince. From that time onward, China called Siam “Hsuan-Lo,” pronounced by Teochew Chinese as “Siam Lo.”

During the Ming Dynasty, Siam and China enjoyed excellent relations, frequently exchanging envoys; envoys from Hsuan-Lo went to China a total of ninety-seven times. Every emperor of the Ming Dynasty continued the diplomatic practices established by its first emperor.

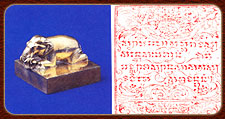

In the Qing Dynasty, Hsuan-Lo continued to send tribute to China. In the ninth year of the reign of Emperor Shun Chih, in December 1652, King Prasat Thong sent envoys with tribute to the Emperor of China and requested a royal seal. The Emperor granted a silver-gilt seal topped with a carved camel. The inscription on the seal read “Hsuan-Lo Guo Wang,” meaning “King of the country of Hsuan-Lo.”

Later, in the seventeenth year of the reign of Emperor Yung Cheng, 1729, he sent another Chinese seal inscribed “Tian Nan Le Guo,” meaning “Heaven of the land of the southern country.”

In the fourteenth year of the reign of Emperor Chien lung, 1749, he bestowed a framed inscription written on paper bearing the words “Yan Fu Ping Fen.” Relations between Siam, or Hsuan-Lo, and China, which had begun in the Song Dynasty, continued into the Qing Dynasty. In the thirty-second year of the reign of Emperor Chien lung, 1767, Burma attacked and captured Siam (Ayutthaya), causing relations to be interrupted until King Taksin the Great, whom the Chinese called “Chen Chao,” reunited the country and sent envoys to China to begin new diplomatic relations.

Relations between Siam and China during the late Ayutthaya period and the Thonburi period, as recorded in Chinese documents, contain interesting facts concerning Thai history during that same time.

In May 1758, the twenty-third year of the reign of Emperor Chien lung, King Borommakot, whom the Chinese called “Wang Po Long Mo Ko,” passed away, and a struggle for the throne occurred. According to the testimony of a Siamese man named “Chen Mo” and a merchant named “Wun Shao,” King “Shao Hua Lao Wang Mi” (meaning King Borommakot, another of his titles, King Thammarachathirat) had two principal consorts. One consort had a son named “Shao Kong” (meaning Krom Khun Sena Phithak, born to Krom Luang Aphaiyuchit, formerly Prince Thammathibet). The other consort had two sons, “Shao Hua Yi Chi Xie” and “Shao Hua Liu Lu” (meaning Krom Khun Anurak Montri and Krom Khun Phon Phinit, born to Krom Luang Phiphit Montri, that is, Prince Ekkathat and Prince Uthumphon). Prince Shao Kong behaved improperly, so King Borommakot commanded another son (born to another consort) to execute him. However, Shao Kong had two sons, “Shao Ya Le” and “Shao Si Chang” (Prince Koet and Prince Chuen). When King Borommakot died, some nobles desired the throne. The first son of the second consort, Shao Hua Yi Chi Xie, should have succeeded, but because he was not strong, his younger brother, Shao Hua Liu Lu, ascended the throne instead. This displeased the elder brother, who attempted to reclaim the kingship.

Shao Hua Liu Lu abdicated in favor of his elder brother and entered the monkhood at Wat Pradu, so the public called him “He Sang Wang,” in Thai known as Khun Luang Ha Wat. The elder brother who ascended the throne was called “Ma Fong Wang” by the people, meaning Khun Luang Khee Ruen. The sons born to other consorts were dissatisfied and attempted to send letters to King U Tu Phan (Burma) in 1758, the twenty-third year of the reign of Emperor Chien lung. At that time, the Alaungpaya Dynasty of Burma, under King Aungzeya, attacked Manipur, which the Chinese called “the Kingdom of Baigu.” The Ta-leng people (Taling or Mon) fled Burma to reside in the Ayutthaya Kingdom. Burma also attacked Negrais. Later, the Ta-leng sought revenge against Burma, prompting the Burmese king to attempt to eliminate them, which led to an invasion of Siam. However, the prince was aware in advance and eliminated the other sons. Another reason for the discontent of the other sons was that Ma Fong Wang had a brother-in-law, Phaya Hanai (Phra Ya Ratchamontri Borirak, Pin, elder brother of the principal consort), from whom he took advice exclusively. Others disliked Phaya Hanai, who, realizing this, informed Ma Fong Wang, who then sent him to “Liu Long Cha” (location not recorded in Thai chronicles), west of Ayutthaya.

Moreover, Chen Mo also reported that Shao Wang Ji, a younger brother of Khun Luang Khee Ruen at that time, was fifty years old, and that one consort of King Borommakot was a Bai Tou Fan (presumably Mon).

Chinese records further note that in November 1760, the twenty-fifth year of the reign of Emperor Chien lung, Phaya Hanai attempted to establish relations with Burma, and the Burmese invaded Thai borderlands twice. That year, King Ekathat (Khun Luang Khee Ruen) was ill. Phaya Hanai attempted to persuade Burma to go to war, but Khun Luang Ha Wat learned of it, and Phaya Hanai was killed beforehand. The Burmese king, Mang Nong (King Mangrok or Alaungpaya), launched an invasion of Siam but contracted smallpox and died en route at Satem. The Burmese army withdrew. Upon his death, King Mangloke (Son Naungdaw-Gyi) succeeded, called “Mang Ji Ze Wei” by the Chinese, sometimes “Mang Luo” or “Mang Nao.” He moved the capital from “Mu Su” (Ratanasingh, formerly the village Muk Chopo) to “Si Zhou” or Takong/Sagaing. People thus called him “Sagaing Min.”

Regarding Ayutthaya, it appears that Shao Wei (presumably another name the Chinese used for Krom Muen Thepphiphit) was sent to another city in April 1762, the twenty-sixth year of the reign of Emperor Chien lung, traveling from Tavoy to “Tan Lao” (according to Thai chronicles, he was exiled to Lanka, but Tan Lao was likely Tenasserim, which the Chinese sometimes called Tan La). Later, in 1763, the Burmese king passed away, and his younger brother Mangra (Mydu) ascended the throne as King Hsinbyushin, meaning “King of the White Elephant.” At his birth, there were ants at his cradle, so he was called “Mang Pwo.” This king was said to be the most intelligent among his three brothers (according to Thai chronicles, there were seven) and highly skilled in warfare. During his father’s lifetime, he had accompanied military campaigns in many places, so records of him were particularly noted. This Burmese king moved the capital back to Mu Su and later to Ava (Ahwa).

In 1764, the twenty-ninth year of Emperor Chien lung, the Burmese king sent his younger brother to lead an army against Siam and his son “Mang San” to attack the city of Hanthawaddy. That year, Burma sent 3,000 soldiers by boat and communicated with some Thais within the kingdom to gather intelligence. People from Tavoy, Tan Lo, and up to Burmese territories sided with Burma.

Two Chinese men, “Chai Kaichun” and “Yang Yawu,” reported that the Burmese army attacked the city of “Taw Hai” (probably Tavoy). In the winter, Taw Hai fell. In January 1765, Shao Wang fled to “Luo Yong” (likely a corrupted form of Shao Wei, referring to Krom Muen Thepphiphit, who escaped from Tenasserim to “Hau Yong,” meaning Phetchaburi). However, the Thai border city “Tan La” (Tenasserim) could not be captured by Burma because the townspeople resisted and evacuated, leaving the city deserted. The Burmese occupied Taw Hai and also captured Wang Ge without opposition on 13 July 1765, the thirtieth year of Emperor Chien lung. The Thai commander “Piao Ya Pa Li” (Phra Ya Rattanathibet from Nakhon Ratchasima province) fled the city, while the deputy commander “Wang We Li” (identity not found in Thai chronicles) was killed. Later, in January 1766, Shao Wang Ji traveled to “Wan Buo Pa Liu Wang Kong” (unable to identify). Shao Wang, aware that Burmese forces were following, established a city at “Gao Liao Fu Yi Tou Mu Su An Li Wang” (unable to identify). In the spring, the Burmese army captured the capital. Thai forces could not catch up, but a group of Thai soldiers established a camp under a leader named “Yao Hua Pao” (likely Phra Ya Kamphaeng Phet, later King Taksin).

Another report states that the Burmese army captured the capital and attacked forty-seven Thai military camps. Consequently, the entire country was filled with Burmese soldiers. All government officials attempted to remain with their families and did not fight, except for some Chinese who resisted the Burmese. During this period, the country suffered from poverty, war, disease, and famine, with an estimated one hundred deaths daily. In January 1767, the thirty-second year of the reign of Emperor Chien lung, Chinese residents fought the Burmese by constructing defensive walls. In February, the Burmese attempted to breach the walls; part of the wall collapsed, leading to seven days and nights of fighting. About 3,000 Burmese soldiers were killed, but the city ran out of food and water, making prolonged defense impossible. On 21 February, the walls were destroyed. In March, the Thai king, Ekathat (Ma Fong Wang), was captured by the Burmese. He offered to present tribute to Burma, but the Burmese commander Thihapate refused and took him prisoner. On 9 May, the Thai capital was destroyed. King Ekathat escaped to “Phow San Thuan” (Pho Sam Ton; this part does not match Thai chronicles) but was eventually executed. His younger brother, Khun Luang Ha Wat, officials, palace women, and all valuables in the royal treasury were taken by the Burmese. On 25 May, the Burmese army withdrew, leaving the commander “Sung Yi” (Suki/Chuk Kyi) to oversee the city. Thus, the Thai kingdom called “Da Chen” by the Chinese came to an end due to the Burmese destruction. This kingdom had prospered for 417 years under thirty-three reigns.

Afterward, a new Thai king emerged, “Chen Chao” (King Taksin the Great), who established a new dynasty called “Tongudi” (Thonburi). Upon coronation, he was titled King Borommaracha IV, but China referred to him as “Chen Chao,” meaning the King of Chen.

According to Thai chronicles, Chen Chao’s original name was Shin or Sin. A Thai named “Mai En Shen” and a merchant named “Chen Ying” called him Phraya Tak. Phraya Tak’s father was from Guangdong, from the town of Xinyong. After moving to Thailand, he married a Thai woman and had a son, Chen Chao, whose original name was “Shen Xin.” In Thai, Shin (Sin) means wealth, so the Chinese rendered it as “Zhen Cai” (Cai meaning treasure). “Chen Chao” was the name used when sending tribute to China during the Qing Dynasty and for official contact with China. The Chinese book “Si Shi Er Mei Zhu Shi” records that Chen Chao’s father was named “Shen Yong” or “Shen Ying” from Chaozhou, in the region of “Chen Hai Wa Huli” or “Deng Hai Fa Fu Li.” Shen Yong came from a wealthy family, was not inclined to work, spent money freely, and enjoyed traveling, so the villagers called him “Tai Si Ta,” meaning traveler.

Thus, due to his poor habits, he became impoverished over time and began traveling south. At that time, there was significant trade between Thailand and China. He gambled and, by luck, became wealthy, changing his name to “Yong” and traveling to Thailand. There he married a Thai woman named “Lue Yong,” or Lady Nok Yang, and their first child, Chen Chao, was born in 1734, the twelfth year of Emperor Yung Cheng’s reign.

Luang Wichitwathakan also wrote a biography of Chen Chao, stating that when King Taksin was born, his father found a snake in the cradle and, seeing it as an ill omen according to Chinese belief, wanted to abandon the child. However, a Thai official named Chao Phraya Chakri thought the boy was attractive and adopted him. At age nine, he studied under a monk named Thong Dee (some accounts say under Master Suk at Wat Phraya Mueang, Wiset Chai Chan District). At thirteen, he entered the royal court as a page. At twenty-one, he left the court to ordain as a monk for three years. After leaving the monkhood, he entered royal service as Tai So (city lord) overseeing Tak. Later, he was promoted to Phraya Wachiraprakarn. Thais revered him, calling him Phraya Tak, Phraya Sin, Phraya Taksin, or Chao Taksin. In Qing Dynasty Chinese records (Cheng), King Taksin was called “Gan Yin Le,” later referred to as “Chen Chao.”

In February 1767, the thirty-second year of Emperor Chien lung, since Burma had attacked the Thai capital for three years and the Thai king was not skilled in warfare, Chen Chao was assigned to defend the capital alongside another official, Po E Biyu Di (Phraya Phetchaburi). Both were capable in defending the city. Chen Chao was tasked with protecting Wat Phichai in the capital, but some officials tried to prevent him from firing weapons, fearing it would alarm the king and palace women. This caused Chen Chao to be disliked. Once, when the Burmese breached the walls, he had no time to report to the king and ordered gunfire, angering the king. Chen Chao no longer wished to defend the capital. According to Ah Yu Tuo, when the Burmese breached the city walls, Thai forces retreated and remained inside, closing the gates. Only Chen Chao led his troops to fight the Burmese, breaking out toward Wat Phichai with 500 soldiers following him.

In May of the same year, Chen Chao captured Chanthaburi. According to Englishman W.A.R. Wood, who recorded King Taksin’s capture of Chanthaburi, the governor of Chanthaburi was friendly to Chen Chao. When he heard that the capital had fallen to the Burmese, he thought he could become king and tried to lure Chen Chao to Chanthaburi to lead an army back to the capital. But Chen Chao anticipated this and captured Chanthaburi at night while the Burmese occupied the capital. At that time, Thais saw multiple factions vying for power, with many states and principalities trying to assert dominance.

“Mung Mo Su Lin,” a resident of He Xian, reported that “Pei Sai Chin” (Phraya Sin) had captured the city of Wang Keo (understood to be Thonburi), while others governed various towns. However, “Sa Wang Ji” (Krom Muen Thep Phiphit), a younger brother of the king, held significant power and was widely respected. Sa Wang Ji led an army to recapture the city of “Gao Liao” (Phimai) and attempted to gather dispersed soldiers while also planning to establish a new capital. Additionally, “Sa Chue Chang” (Chao Srisang, son of Krom Phra Ratchawang Bowon Sathan Mongkhon), a half-brother, fled from Thailand to Cambodia. Another figure, “Sao Te Re” (identity uncertain), and other royal grandchildren escaped to He Qian (likely Sawangburi), where over thirty thousand Thai men and women had gathered.

Sao Te Re reported to the Chinese emperor that he was distressed because the capital had been destroyed by the Burmese, the heir was dead, and the population was scattered; some had been captured by the Burmese. His uncle, Sa Wang Ji, had gone to Gao Liao, while he fled to He Qian. His younger brother, “Si Chan” (Chao Chui, son of Krom Phra Ratchawang Bowon Sathan Mongkhon), was in Cambodia. The Cambodian king showed generosity, granting all requests, recognizing Thailand as the origin of the “Heavenly City,” and because Sao Te Re’s sister had been kind to the people of He Qian. Meanwhile, a Thai official, Phraya Sin, or Chen Chao, sought to establish himself as king, disregarding the Thai royal family, and captured members of the royal lineage as slaves. Chen Chao gathered his army and attacked Gao Liao, where Sa Wang Ji resided. Sa Wang Ji fled near the border of “Lao Kwa” (Srisatchanalai). The governor of Lao Kwa returned Sa Wang Ji, but on the way to Wang Keo, he was executed by Chen Chao. Chen Chao then marched toward He Qian, but the Cambodian king refused him entry. The king promised Sao Te Re and Sa Chue Chang to help reclaim the capital. At that time, Sa Chue Chang was twenty-four, and Sao Te Re was thirty-nine. Sao Te Re could not restore the country alone due to lack of power, while Chen Chao attempted to ascend the throne unofficially.

According to Chen Chao’s report, the previous Thai king resided in the southern palace and had sent tribute to the Chinese emperor for a long time. When he passed away, “Se Hua” (King Ekathat) succeeded him. However, “Sao Wong Ji” (Krom Muen Thep Phiphit, likely a corruption of Sa Wang Ji), a royal relative, attempted to eliminate him but failed. He then conspired with “Wa Tu” (another name the Chinese used for Burma) to besiege Thailand until the capital was captured. The king was executed, and the palace was looted and burned.

At that time, “Zao Wangji” (Sa-wang-ji) seized the entire palace. However, Zao Wangji, Zao Ter, and Zao Tang feared that the people would resist, so they did not return to Thailand, leaving the country without a ruler. They attempted to take revenge but were unable to establish a stable nation, and the border areas remained insecure. Neighboring countries tried to seize control, seeing the lack of leadership. Since the kingdom was in the midst of war, the king and royal relatives stayed abroad and did not return to rebuild the nation, so the people chose a leader themselves.

In the early period when Zheng Zai (Chao Phraya Chanthaburi) captured Chan Juowun (Chanthaburi), the local ruler named “Wang Qian” (the governor of Chanthaburi) surrendered to Zheng Zai and even gave him his daughter. Later, when Zheng Zai captured Trat, nobles and soldiers from various regions joined him, totaling 5,000 men, and they built 100 ships that sailed through the Meilan River (Chao Phraya River). In August, the 30th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, Zheng Zai returned to Wang Ge (Thonburi area) and killed Thong In, a puppet king set by the Burmese, and seized the Burmese camps, also killing Sung Yi (Suki), whom the Burmese had appointed to oversee the area. At that time, Zheng Zai’s army had grown to tens of thousands. He became a key figure not only in reclaiming the country but also in attempting to invite royal relatives back and ceremonially transferring the remains of the previous king according to tradition. Therefore, in January, the 33rd year of Qianlong’s reign (2311 BE), the Thai people decided to choose Zheng Zai as king.

Another record states that during the period when Thailand was occupied by the Burmese, the previous king had died, and the people were impoverished; the country was filled with criminals. “Chao Phaya Kan-en-le” (Chao Phraya Taksin) gathered people to fight the Burmese, restoring order. He united the country and established the capital at Mangu (Bangkok). To ensure the well-being of the citizens, he allowed people to sell forest products and other essential goods. The regional governors feared Zheng Zai due to his strong leadership. As there was no eligible heir to the throne, the people requested Zheng Zai to become king. At this time, he was in Bangkok, but the city was heavily damaged, making reconstruction difficult. Therefore, he decided to establish a new capital in the south at Thonburi, marking the beginning of the Thonburi dynasty. Zheng Zai was 34 years old. It is said that one reason he founded the new capital was that he dreamt the previous kings were driving him out of the old capital. Viewing this as an ill omen, he moved to Thonburi. Moreover, Ayutthaya was difficult to repair, whereas Thonburi had a favorable strategic location, was easy to control, and was near the sea, making it suitable as a trading port.

The reason Zheng Zai did not succeed in sending the tribute to the Chinese emperor for the first time…

In 1765 (BE 2308), the relations between China and Burma began to deteriorate significantly due to border disputes. Later, in 1771 (BE 2310), the 32nd year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, as complications arose along the border, the governor of Yunnan Province, China, named Yang Yingzhu, submitted a memorial to the Chinese emperor requesting that he send 50,000 troops to fight the Burmese on five fronts. He also advised enlisting Thai assistance to resist the Burmese. However, Emperor Qianlong (Gaozong) found Yang Yingzhu’s proposal somewhat absurd. Deploying such a large army and relying on another country to fight one’s enemies was unwise and improper. He therefore refused to follow this advice, noting that even during the Ming dynasty, similar requests for foreign assistance had proven ineffective. Unlike the Ming period, during Qianlong’s reign, the Qing dynasty had abundant military strength both domestically and abroad, and other countries sent tribute missions to support China in opposing Burma. At that time, the emperor was unaware that Thailand had been attacked by Burma and that its capital had fallen.

Nevertheless, the Qing dynasty decided to begin a military campaign against Burma that winter, without requiring troops from other nations. Since Thailand shared a border with Burma, China requested Thai assistance to block any Burmese escape into Thai territory. At that time, Guangdong and Amoy (Ma-kau) were international ports with many trading ships. On June 17, 1771 (BE 2310, the 32nd year of Qianlong), the emperor instructed the governor of Guangdong-Guangxi, named Si-ya, to send a letter to Thailand asking them to monitor any Burmese king who might attempt to flee into Thai territory during the Chinese campaign against Burma. The next day, Thai officials sent a stamped letter regarding this matter to the governor of Guangdong-Guangxi. In September of the same year, a merchant ship from Annam (Vietnam) sailed from Guangzhou. Si-ya entrusted the letter to Chu Chuan to deliver via that ship, intending that upon reaching Annam, Chu Chuan would pass it to officials of “Mosulin,” the governor of Heqian, who would then forward the royal letter to Thai official “Pu Lan Pe.”

On September 9, Chu Chuan dispatched an official named Wang Guozhen to Annam along with another person, the ship owner Yang Jinzong. They all boarded the ship “Moguang Yi” and departed from Fu-men (Tiger Gate). By October 10, they reached the Annam Bay, but due to severe weather and strong winds, the ship could not dock and had to wait. On October 12, the winds worsened, breaking one of the main masts. The next day, the storm intensified further, forcing the ship to leave the bay. Finally, on November 3, the vessel arrived at “Lu-kwin,” likely Nakhon Si Thammarat, often abbreviated as Lakhon.

During this period, Chu Chuan fell ill with cholera. His bodyguard, named Mi Shen, reported the situation to officials at Lukwin. On November 5, they brought Chu Chuan ashore to Wu Di Temple. Officials in Lukwin sent a doctor named Nai Su Nai Jian to treat him. Mi Shen also sent a Chinese doctor to examine Chu Chuan because he did not trust the local physician. Despite these efforts, Chu Chuan passed away on November 15. It was later reported that Wang Guo Zhen contracted the disease, fell ill on January 1, 1768 (BE 2311), and died on January 22 of the same year.

On January 2, 1768 (BE 2311), the 33rd year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, the emperor instructed officials to send a letter to Siya to closely monitor the situation in Thailand. The letter indicated that if the Thai king decided to reunify the country but lacked sufficient power, and requested Chinese military assistance, China would gladly send troops. At the same time, China requested Thai cooperation in fighting Burma.

On August 1 of the same year, Zhen Jia (King Taksin) sent an official named Chen Mei to present a royal letter to Emperor Qianlong. The letter stated that Zheng Pa Ya Gan En Le (Phraya Tak) had paid homage to the emperor three times and bowed nine times in respect. The Thai king and people wished to show their loyalty, so that neighboring states would not dare to attack. However, Burma had already invaded Thailand three times, and the capital had been destroyed. Zhen Jia humbly requested the emperor’s assistance, confident that China would help prevent Thailand from losing its sovereignty to Burma. At that time, the Thai king, his two younger brothers, and other officials were unable to restore the country. Zhen Jia therefore requested help from “Zhan’er Wen” (Chanthaburi—another Chinese pronunciation of “Zhan Jie’ouwen”). But upon arrival, the city had already fallen, and the population had fled due to widespread famine. The letter emphasized that if the emperor could witness the suffering, he would surely feel compassion. Historically, Thailand had sent tribute to China, which the emperor had graciously acknowledged, earning the respect and fear of neighboring states. Yet now, the country was in chaos, with bandits in the forests and no ruler to maintain order. Zhen Jia reported that his forces were fighting U Tu Fan (Burma) and Wen Si (likely the Mon people) because both had sent armies to attack. Through the emperor’s blessings, Zhen Jia’s forces were able to continue resisting Burma and achieved victories. However, he had not yet located the younger brothers of the former king to invite them back to resume the throne, because Hu Si Lu, Lukwin, and Gaolia were all within the Ava kingdom and did not submit to Thailand.

Therefore, I humbly request Your Majesty’s gracious assistance to help Thailand return to its former prosperous state, respected and feared by neighboring countries, and to eliminate the bandits. However, since we have limited money and food, we have sought ivory, fine wood, and birds to trade for money to buy provisions. Furthermore, we lack sufficient officials, and thus cannot yet suppress the small independent principalities. If Thailand had a new king who was wise and capable, and if Your Majesty recognized him as the legitimate ruler, the people and the army would unite to subdue the independent states.

I have sent a ship full of tribute to Your Majesty, and I pledge to serve Your Majesty faithfully forever. If Burma sends an army again, we will fight. If Your Majesty dispatches troops to subdue Burma, we will follow Your commands. Nevertheless, I am uncertain whether my request will succeed, because I do not know how the previous kings sent their tribute. The royal decrees and laws of the past were all destroyed during the war. If Your Majesty graciously allows me to learn the proper regulations, I will send tribute in accordance with what the former kings sent.

In that same year, the leaders of other independent states also sent messages to the emperor of China, requesting recognition as the legitimate kings of Ayutthaya, succeeding the previous kings who had died during the war. With several independent states still in existence, Jen Chao had not yet been able to fully unify the country. Thus, the emperor of China had not yet recognized Jen Chao as king. If Jen Chao wished to gain recognition from neighboring countries, he would first need to receive a special royal title from the Chinese emperor. Once granted, Jen Chao would hold a distinguished status in the region. Even though the people had sincerely chosen Jen Chao as king of Thailand, this recognition from the Chinese emperor would carry far greater weight, ensuring acknowledgment and respect from neighboring states.

The official who carried Jen Chao’s letter to the Chinese emperor was Chen Me. Another letter was delivered to the governor of Guangdong-Guangxi, named Li Siya, who presented Jen Chao’s message to the emperor. He also advised the emperor on whether a reply should be sent to Jen Chao. Additionally, the governor reprimanded Chen Me for not following proper protocol.

On August 19, 1768 (BE 2311), the 33rd year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, the emperor agreed with the proposal submitted by Li Si Yao because he believed that Zhen Jao was an ordinary person and should not behave in the same manner as former Thai kings had done toward the emperor.

The content of the letter drafted by the governor of Guangdong–Guangxi for Emperor Qianlong to review before sending it to Zhen Jao stated that Gan En Le was an ordinary commoner who had wandered like a pirate, making him more suited to be a leader of pirates than a king. He should not compare himself to a monarch. Although the Thai kingdom had been in danger and Zhen Jao had helped save it, he still had no right to become king. Even if he succeeded in restoring the country’s independence, which was commendable, his attempt to make himself king despite lacking royal lineage could not be accepted.

Li Si Yao reprimanded Chen Mei for these improper actions. Although Emperor Qianlong agreed with Li Si Yao’s reasoning, he criticized Li Si Yao for handling the matter disrespectfully toward Chen Mei. The emperor instructed Li Si Yao to send a letter with explanations to help Zhen Jao understand that China respected the law and proper order. China could not accept anything that deviated from long‑established customs. Since others also sought recognition as the king of Siam, China had to act consistently, as Zhen Jao appeared to have seized the position of the previous king. Emperor Qianlong also advised Li Si Yao to explain this clearly to others who claimed the Siamese throne, rather than only reprimanding them without clarification. After receiving the imperial instructions, Li Si Yao wrote two letters: one for Chen Mei to take back to Zhen Jao, and another to be sent to the governor of He Qian, named Mo Si Ling (Chao Phraya Fang Ruean). Because Li Si Yao was not confident in drafting the letters correctly, he asked another official to prepare both letters, after which he personally reviewed them before handing them to Chen Mei. The letter stated: “The request for China to recognize Zhen Jao as king and to grant a special royal seal cannot be accepted because it does not follow established tradition. Properly, Zhen Jao should search for the rightful heir to the throne, assist him in restoring the nation, and enthrone him as king. Zhen Jao has not done this but instead made himself king. China therefore does not approve of such improper and immoral conduct. Furthermore, there are still three other independent states that continue to resist and oppose you, such as Lu Si Lu. This is because you are not the rightful heir. You should honor the former kings and therefore must search for the rightful heir and assist him in restoring the nation.”

As for the letter that reached Mo Si Ling, it stated that the Qianlong Emperor did not in any way acknowledge Mo Si Ling. However, Shao Te having fled to Heqian, and Mo Si Ling offering support and assistance, was considered a good act. He was regarded as someone knowledgeable in customs and traditions and as a man of virtue. Therefore, we are granting him a robe as a sign that we approve of the actions he has taken.

From this account it appears that Siam had seemingly long been under China’s authority, as tributary missions were continually sent to the Chinese emperor. China therefore respected the Siamese kings, and when Zhen Zhao tried to set himself up as king, China refused to acknowledge him because they knew the rightful heir was still alive. The special title that China had previously granted was thus still valid, but China would not grant a new one to Zhen Zhao. This was the first time Zhen Zhao failed in his initial attempt to offer tribute to China.

The second tribute mission

In September 1768, the 33rd year of the Qianlong reign, “Sa Wang Ji,” the Siamese heir apparent, traveled from Wangke back to the capital. But on October 25 he was executed. At that time Li Siyao, the governor of Guangdong–Guangxi, had already sent a letter to Zhen Zhao more than two months earlier, yet the emperor had not received any reply from Zhen Zhao. Meanwhile, in the Burmese campaign, China had dispatched the official “Chen Che” to fight against Burma and had captured Ava. Later, there was still no report sent to China regarding how Siam was attempting to reunify the country. But Mo Si Ling, the governor of Heqian, sent a map of sea routes showing the passage from Guangdong to Burma and to Siam, along with a memorial stating what he intended to do in the future. For this reason the Qianlong Emperor sent an official to deliver these matters to Li Siyao and ordered Li Siyao to select officials to travel to Heqian as quickly as possible to inquire about affairs in Siam and send reports to China. Li Siyao obeyed and selected “Zhen Re” and “Chen Tayong” to board a merchant ship to Heqian.

Another official China had sent to fight the Burmese was “Ming Re,” but he was killed. The Qianlong Emperor therefore sent Fu Hen to command the campaign and sent “A Li Guan” and “A Gui” as advisers. These officials feared that “Mong Pang,” the Burmese king, might flee to another country. Therefore, the Qianlong Emperor ordered Fu Hen to contact the governor of “Nansang” and request assistance in jointly resisting Burma.

On June 20, 1769, the 34th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, the emperor ordered an official to draft a plan to begin military operations against Burma and sent a letter to Li Siyao to have it stamped and forwarded to Thailand. The letter requested Thailand’s assistance in preventing the Burmese king from fleeing through Thai territory. The emperor also inquired whether Zhen Zhao had located the true heir of Thailand, if he had contacted the Sa family, who were heirs of the Thai royal line, and whether they were cooperating to reunify the country. He asked whether Zhen Zhao was still managing affairs within the country, and if so, requested that Zhen Zhao report these matters to China, as the emperor wished to know who was the king of Thailand at that time.

On June 27, Zhen Re and Mo Wenlong, officials sent by Mo Si Ling from Heqian, embarked from Heqian to Guangzhou, carrying two letters from Mo Si Ling to the emperor. One letter reported the situation in Thailand, and the other described the situation in Burma. Zhen Re reported on the events between Thailand and Burma and described the sea routes between China and Thailand. According to Zhen Re’s report, Mo Si Ling, governor of Heqian, had sent Chen Lang to lead an army against Zhen Zhao in December of the previous year, capturing the city of Tongzhai in January. In February, Mo Si Ling sent Chen Ji to assist Chen Lang and attempted to attack San Se Wen (likely Sawankhalok). Chen Ching-sang was also sent, but before he arrived, Chen Lang had already captured San Se Wen and taken the local ruler, Ling Gongxun, to Heqian. Chen Ching-sang then led 2,000 troops to attack Wangke, where Zhen Zhao was established, but Zhen Zhao’s forces were strong, and Chen Ching-sang was unable to seize the city easily. The letter further explained that Zhen Zhao had declared himself king, executed Sa Wang Ji, the heir, and taken the palace women for himself. He had committed many crimes, and the people disliked him. Several independent states were cooperating to resist Zhen Zhao in order to restore the country.

Li Siyao praised Mo Si Ling for his actions, noting that he had done well to protect the people from danger. Since Emperor Qianlong did not fully understand the situation in Thailand, he sent officials to investigate further. Upon receiving Mo Si Ling’s report, the emperor concluded that Zhen Zhao was a dangerous person causing disorder and attempting to establish himself as king.

On July 4, Li Siyao received an imperial edict to return the original letters intended for Thailand to the capital. Li Siyao reported to the emperor that the Thai heir had not yet been found, but Mo Si Ling, the governor of Heqian, was obedient, humble, and courteous. Mo Si Ling had captured San Se Wen and was also gathering other states to resist Zhen Zhao. This demonstrated that Mo Si Ling had sufficient power to oppose Burma and had acted in accordance with the emperor’s orders.

On July 5, 1769, Li Siyao acted on his own initiative by sending a bandit unit led by Cai Han to Heqian. He delivered a letter along with silk and clothing to Mo Si Ling. The letter was a copy of the message Emperor Qianlong had sent to the Thai king, requesting Thailand’s assistance in resisting Burma. However, the emperor did not approve of Li Siyao’s action.

On July 14, Emperor Qianlong wrote to Li Siyao that Thailand had been unable to locate the royal heir, and real power rested with Zhen Zhao (Kan En Le). It was difficult to find the original heir to reunify the country. Since Thailand already had someone in power, the Qing administration changed its previous attitude toward Thailand, preferring not to interfere in the ongoing internal chaos.

On July 18, Li Siyao sent the emperor’s letter to Mo Si Ling, noting that Thailand was too distant for China to control. The letter opposed Zhen Zhao’s seizure of power and attacks on cities and emphasized the need to prevent Zhen Zhao from consolidating the country. Nonetheless, Mo Si Ling still sought to assert authority. A Chinese general fighting Burma reported that Mo Si Ling had done everything possible to help restore the nation, earning high praise from the general.

In November, Zhen Zhao captured Lukwin and began attacking Mo Si Ling’s territory, reclaiming San Se Wen. The following year, he recaptured Husi Lu. Zhen Zhao then controlled northern Thailand and, in reality, could have reunified the country at that time.

On December 4, a Chinese naval commander arrived in Heqian, and Mo Si Ling sent an official to take his letters to Guangzhou to present to the emperor. The letters stated that Thailand had no king, the royal heir had disappeared, and only two or three former officials retained some power, which was not substantial. Mo Si Ling noted that he had done his best.

Li Siyao responded to Mo Si Ling, acknowledging receipt of the letters and recognizing Mo Si Ling’s efforts. However, he questioned why, when the Thai king was in danger and Sa Te Le had fled to Heqian, Mo Si Ling had captured Sa Te Le but did not assist in reunifying the country. Li Siyao noted that Mo Si Ling had not responded to repeated imperial inquiries and seemed only concerned with his own position. This indicated that Li Siyao had begun to doubt and become dissatisfied with Mo Si Ling.

In May 1770, Cai Han, the Chinese bandit leader, sent a letter to Zhen Zhao requesting help in capturing the Burmese king. In December, Zhen Zhao attacked and recaptured Chiang Mai from Burma. According to testimony from a Thai official named Kun Mi Xi Neocha, Zhen Zhao led 40,000 troops, with an additional 20,000 from the eastern towns, and laid siege for several days. However, lacking food and gunpowder, they had to withdraw.

During this campaign, Zhen Zhao captured Fa Tu Fan, Xie Tu Yanda, ten men, 41 women from Chiang Mai, and maps. He handed them to four Chinese generals—Hou Pa Chan Pei Huan Si Tu, Kuan Mi Zhe Xi Nei Cha, Hou Xuan Tuan Wan Ni Su Xi, and Xie Kai Chuan—to be taken to Guangzhou. These names do not clearly match Thai records.

On June 9, Cai Han returned to Guangzhou to deliver letters from Mo Si Ling and Sa Te Le to the Chinese emperor. Mo Si Ling reported that he had acted according to the emperor’s instructions and had contacted neighboring states to help resist and destroy Burma. He had also gathered neighboring states to assist China in fighting Burma. However, Zhen Zhao had captured Lukwin and attacked Mo Si Ling’s territories, attempting to seize goods that had been sent by the emperor the previous year, despite Mo Si Ling having already sent Sa Te Le to him.

On July 26, 1771, Hou Pa Chan Pei Huan Si Tu and others reached Nanhai, Guangdong Province, and requested Wu Wu Han, the local governor, to report to Li Siyao. Two men and ten women died en route, leaving only 39 people to arrive in Guangzhou. According to the captured Chiang Mai official, Ne Qie Tu Yanda, he had served under the Ava prince named Zuyin Aen Ma A Ge Li, who initially attacked Chiang Mai and appointed the father of one of his concubines as ruler of Chiang Mai, named Na Niu Ge Ma Ni Jiao Te. Ne Qie Tu Yanda became an official in Chiang Mai and was sent to guard the Wan Na Guo Qili region. That same year, Thai forces attacked Chiang Mai, and Ne Qie Tu Yanda was injured by gunfire and captured.

Li Siyao selected four male and four female captives, the oldest of whom were sent to the capital for questioning by the imperial court. Ne Qie Tu Yanda and twelve others were sent as slaves to Helongzhang, according to Guangdong Province regulations on prisoners. The remaining 27 women were sent to serve as slaves around the city. Afterwards, Hou Pa Chan Pei Huan Si Tu returned to deliver letters from the governor of Guangdong to Zhen Zhao. The letters stated that the imperial seal of special rank previously granted to former kings had likely been lost during Burma’s invasion of Thailand. Therefore, Zhen Zhao was requested to have the opportunity to offer tribute as before. The letter praised the Thai people as pleasing to the emperor. This demonstrated that Zhen Zhao was trying to gain favor with the Chinese emperor by sending captives to China.

On August 17, the emperor received a report from Li Siyao and wrote to him that Zhen Zhao had sent the Burmese captives in order to obtain permission to send tribute. The emperor instructed that Zhen Zhao should be allowed to present tribute, as he had shown loyalty and followed Chinese protocol, and thus it was decided to send him robes.

On September 7, Li Siyao received the emperor’s letter and prepared two types of silk, two rolls each, to send to Zhen Zhao. On October 18, the emperor sent another letter to Li Siyao, noting that small states often lacked morality and engaged only in warfare, citing Annam (Vietnam) as an example for repeatedly changing kings. In Thailand, Zhen Zhao had seized power during Burma’s invasion. Nonetheless, he had acted according to China’s request and had sent forces to attack Chiang Mai, capturing a Burmese general, showing he remained opposed to Burma and respected China. Therefore, the emperor advised that Zhen Zhao should not be rejected simply because he was not of the former royal lineage. Zhen Zhao had attempted to rebuild the country, so China should not oppose his sending of tribute. If opposed, he might ally with Burma, which would be unwise. The emperor instructed Li Siyao to inform Zhen Zhao that he would be granted a rank. At the same time, Fu Ren, a Chinese official, returned to China after failing to negotiate with Burma due to the Burmese king’s obstinacy. The emperor, understanding the situation, resolved to cooperate with Thailand.

On October 6, 1771 (BE 2314, 36th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign), Zhen Zhao sent an army to attack Heqian, appointing Chen Lian (Phraya Phichai Racha) as commander and naval captain Yang Jinzong (Phraya Yommarat) as vanguard. Since Mo Siuling lacked sufficient troops, he was defeated on October 9. Mo Siuling fled to Lu Xian (location unknown) in Annam (Vietnam). All weapons, personnel, and the royal heir were captured by Zhen Zhao’s forces, and Chen Lian was left in charge of Heqian.

In May 1772 (BE 2315, 37th year), Zhen Zhao sent captives to China with a letter to Li Siyao explaining that during the previous winter, he had sent forces to the Bay of Bendai, where 35 Chinese people from Guangdong, Guizhou, and Haiphong had been stranded. They had been intending to farm in Yangzhang since 1768 but were lost at sea. Mo Siuling had refused to return them, so they remained there for six years. Zhen Zhao provided them food, water, and money. Among them, Chen Junqing and Yang Sanguan were sent back to Guangdong by two ships: one commanded by Su Yuanchen carrying Yang Sanguan, nine men, and eight women; the other by Qi Pu carrying Chen Junqing, 12 men, and four women.

On June 6, Yang Sanguan arrived in Guangzhou and reported to the city officials, giving a different account than Zhen Zhao’s letters. He stated that he had not gone to Yangzhang to farm but had sought farmland in Bendai, recruiting family and hiring a ship under captain Hu Longzong. Mo Siuling had not coerced them. Li Siyao concluded that Mo Siuling and Zhen Zhao were long-time adversaries, and Zhen Zhao falsely accused Mo Siuling of detaining Chinese people to prevent him from reporting to the emperor. Mo Siuling had attempted to retain the royal heir to maintain power, while Zhen Zhao sought to capture him. Li Siyao advised Mo Siuling to protect himself and the people to gain respect, noting that Zhen Zhao had returned Chinese people to Guangdong, shown loyalty, and requested special rewards from the emperor. This demonstrated that Zhen Zhao repeatedly attempted to gain favor with the Chinese emperor by sending tribute, while Mo Siuling tried to ally with the emperor and discredit Zhen Zhao. Consequently, the two often opposed each other. When Mo Siuling moved troops to return the royal heir, Zhen Zhao’s forces attacked at Zhanjeowun, causing most troops to be injured and forcing a return to Heqian. Mo Siuling reported to China that his defeat was due to misfortune, as Zhen Zhao attacked and sought the special imperial seal, which had been lost during the previous Burmese invasion. Mo Siuling followed imperial protocol and would have assisted the true royal heirs if they attempted to restore the country. However, Zhen Zhao, not being the legitimate heir, repeatedly requested the seal and custody of the heirs, prompting Mo Siuling to resist him.

Regarding the seal, which became a prolonged issue, it originated on April 14, 1766 (BE 2309), the 31st year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, when the Thai king of Ayutthaya sent a minister named Pa Ya Ke Tong He Fei to the Chinese capital at Nanjing. The Chinese emperor granted a special seal to the Thai king, along with gifts such as multicolored fabrics, jade items, glassware, and fine porcelain. At that time, Ayutthaya had been attacked and defeated by Burma. The envoy informed the Chinese emperor that the king had passed away, and he took the gifts to Guangzhou. On October 30, 1768 (BE 2311), the envoy departed by ship to return to Thailand. Later, when Zhen Zhao wished to present tribute to the Chinese court, the seal was required, because the relationship between China and Ayutthaya was considered that of a lord and his vassal.

Ayutthaya had a relationship with China like that of a lord and his vassal. When Mo Siuling returned the seal to Guangdong, the relationship between Thailand and China was disrupted. Later, when Zhen Zhao unified the country and wished to present tribute to the Chinese emperor, the absence of the seal caused him to be angry with Mo Siuling for having returned it.

Details of the fourth diplomatic contact:

On August 4, 1774 (BE 2317), the 39th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, Changde, an official at Nanhai in Guangdong Province, reported that a merchant ship belonging to Chen Fuchen, which was headed for the country of Folo, was blown off course by rough weather and drifted into Thailand. A Thai official brought the ship to Guangdong and submitted a report stating that Zhen Zhao had been striving with great effort to avenge the former king and resist Burma. Because his territory was near the sea but lacked sufficient weapons, he requested to purchase 50 loads of sulfur (150,000 kilograms or 150 tons) for making gunpowder, and 500 iron pans for casting cannons. Li Siyiao observed that Zhen Zhao had controlled Thailand for seven years, remaining at Wangke without returning to the former capital, and that he was now seeking to buy more weapons to fight other states opposing him. Therefore, Zhen Zhao was attempting to win the favor of the Chinese emperor to gain trust. China understood that he was striving to defend the territory on behalf of the Thai king, and thus they should not forbid him. From this letter, Li Siyiao drafted a memorandum for the Chinese emperor, submitting the message intended for Zhen Zhao: it was good that he was attempting to avenge the former king, and they understood his need for weapons, but he must not forget the former king and should avenge him. However, under Chinese law, sulfur and iron pans could not be sold to anyone without a special imperial decree. The emperor marked the memorandum in red ink, indicating his agreement.

Zhen Zhao had already established a new capital at Thonburi, but Li Siyiao misunderstood the situation, thinking that Zhen Zhao did not dare to return to the old capital. That same year, Thailand and Burma fought again. Thailand needed many soldiers and sulfur, since it could only produce saltpeter domestically, which was why Zhen Zhao wished to buy sulfur from China.

A Chinese man sent back to Yunnan, Yang Chaopin, testified that in April of the 34th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign (1770, BE 2313), he went to Manzi (Cambodia), which the Mianzi (Vietnamese) had seized and called Tama (Phutthaimat), a coastal town whose inhabitants made a living by fishing. Manzi had more than 10,000 people and was under Vietnamese control. In the 39th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign (1774, BE 2317), the Mianzi attempted to invade Thailand. Zhen Zhao asked Manzi for 1,000 men, requested that they provide and transport provisions, and asked them to supply silver ore, but Manzi was unable to comply due to great difficulty.

The Mansi forces killed the Mianzi general and fled to Burma. Later, the Mianzi sent troops to seize Mansi, reaching the city of Mipu (Phutthai Phet). Battles went back and forth, with victories alternating. Mipu was a broad plain, making it difficult to win easily. Since the Thais knew the terrain well, also called “Lapo” (Baphnom), which was mountainous, the fighting took place at “Geopu” (Kampot). The Mianzi established camps around the hills for one month. The Thai forces achieved victory, capturing 6,000–7,000 prisoners and transported them back to Thailand.

Details of the fifth diplomatic contact:

In August 1775 (BE 2318), the 40th year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, a merchant named Chen Wanshen (or Chen Wansen) delivered a letter from Zhen Zhao to the Chinese emperor. The letter stated that Zhen Zhao had captured the city of Chiang Mai (Chingmai) and taken people from Dama as prisoners, including 19 soldiers from Yunnan, one named Xiao Chenjiang. Due to the necessity of continuing the fight against Burma, Zhen Zhao respectfully requested the emperor’s permission to purchase weapons. Li Siyiao was initially skeptical of Zhen Zhao’s account and questioned the Chinese who had been sent back from Thailand. They testified that in August of the previous year, the Burmese had attacked Dama and fought up to Thailand’s borders, which differed from Zhen Zhao’s account. Nevertheless, because Zhen Zhao had returned the Chinese from Yunnan—a gesture demonstrating loyalty to the emperor—if he wished to purchase weapons and iron pans, the emperor would permit it according to the previous year’s requested list. However, cannons were still not authorized. The emperor sent instructions to Li Siyiao to draft a reply to Thailand.

Details of the sixth diplomatic contact:

In 1776 (BE 2319), the 41st year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, the merchant Mo Guangyi delivered a letter from Zhen Zhao to China along with Yang Chaopin and Zuan Yijin to return to Yunnan. In Zhen Zhao’s letter, he reported that Thailand had been fighting Burma for several years and requested to purchase 100 loads of sulfur (300,000 kilograms or 300 tons) once again. He also asked that if China planned to send troops to attack Ava, the dates be provided so Thailand could coordinate and attack Burma from another front. The three individuals sent were actually merchants seeking special permits to sell goods in the city of Mupang on July 16 of the previous year, but they had been captured by Burma en route to Ava and fled to Mansi before entering Thailand.

On 10 October 1776 (BE 2319), Li Siyiao drafted a memorial on this matter and submitted it to the capital. The Chinese emperor then ordered Wu Minzhong, a general, to send a letter to Li Siyiao stating that whenever Zhen Zhao encountered Chinese people in Thailand, he would assist them by sending them back to China as a gesture of goodwill toward the emperor. Previously, China had allowed him to purchase sulfur and iron pans, and this time he was permitted to buy the same quantities again. Li Siyiao sent this letter to inform Zhen Zhao that after he had unified the country, he had initially wished to request a special official seal from the emperor. He then attempted to assist China in fighting Burma, capturing the Burmese general who held Chingmai and sending him to China, as well as sending Burmese prisoners to China. These actions demonstrated loyalty toward the emperor. As Zhen Zhao’s military strength grew and he sent troops to attack Burma, he needed more weapons and wished to purchase war materials such as sulfur and iron pans from China. Since he had acted carefully and shown humility toward the emperor, Li Siyiao permitted him to buy weapons.

Details of the seventh diplomatic contact:

In April 1777 (BE 2320), the 42nd year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign, Li Siyiao drafted a letter to be sent to Zhen Zhao and submitted it for imperial approval. The letter stated that it was known Zhen Zhao continued to request a special title so that he could rule the country. Li Siyiao recalled that earlier the emperor had said that foreign states requesting special titles for the purpose of presenting tribute did not need to send too many missions. Thus, if Zhen Zhao attempted to send tribute again, the emperor instructed Li Siyiao to assess the situation and submit a report. At first, Li Siyiao suspected that Zhen Zhao was trying to consolidate internal power and would use the special title from the emperor to strengthen his authority. This seemed likely because no one had directly witnessed the events in his battles with Burma. However, Li Siyiao became convinced of the truth after consistent testimonies from Sun Boqiang, an official, and Yang Chaoping, a commoner, both stating that Zhen Zhao had killed large numbers of Burmese soldiers. Additional reports from sea‑trading merchants said that Zhen Zhao’s closest friend was a fierce enemy of Burma. This reflects an effort to encourage Zhen Zhao to send tribute to the Chinese emperor in hopes of being recognized as the legitimate king of Thailand.

At the time, relations between Burma and China were poor, and Qing forces had suffered defeats. Li Siyiao, already governor of Guangdong and Guangxi, was attempting to extend influence over Yunnan and Guizhou. Thus, he sought to encourage Thailand to send tribute, aiming to persuade Thailand to attack Burma from the rear. The Chinese emperor agreed with this plan but did not wish to send a royal letter himself. Instead, he instructed Li Siyiao to correspond with Zhen Zhao directly and ordered Yang Jingsu to deliver the letter to Thailand.

In June of the 42nd year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign (1777 CE, BE 2320), Zhen Zhao sent Phraya Suai Thuan Yaphai Natthu (Phraya Sunthorn Aphai Racha, the royal envoy) to Guangdong to request imperial permission for Siam to present tribute. At that time, the Chinese authorities considered Zhen Zhao to be highly trustworthy. Since the Siamese could not locate the royal heir, China began to recognize Zhen Zhao and allowed Siam to send tribute. However, Siam was extremely poor, with little in the royal treasury to offer, due to ongoing wars with Burma and the effort to unify the country. Zhen Zhao therefore requested a postponement of the tribute mission.

On 29 June, Chen Dayang, the head of a band of rebels in Guangzhou, reported that a merchant ship from Siam was returning to Guangdong, carrying three Siamese officials with tribute for the Chinese emperor, along with fifteen soldiers and six Burmese prisoners. Li Siyiao initially did not send a letter to Zhen Zhao, planning instead to coordinate it with the arrival of this envoy. Meanwhile, Guangdong’s governorship had changed hands to Yang Jingsu, who assigned the official Piao Pian to receive the three Siamese envoys.

On 1 July, the Siamese officials presented Zhen Zhao’s letter to the emperor. Yang Jingsu informed the local governor, Li Shuying, to welcome the Siamese officials—Phraya Suai Thuan Yaphai Natthu and two other officials—and to gather details from them. The Siamese explained that Zhen Zhao had acted to avenge the former king and to please the Chinese emperor, and that presenting tribute would strengthen his political authority, secure recognition from neighboring states, and aid in resisting Burma. They also explained that the previous year Siam had captured 300 Burmese prisoners; some, like Ai Ke, Ai Suai, and Ai Yao (close officials of the Ava ruler), were sent to China, following Chinese law that required imperial permission to transfer foreign prisoners.

However, since Zhen Zhao had taken control of Siam, he had not yet received a special imperial seal from the Qing emperor, so he sent tribute with great respect. The original seal, granted during Ayutthaya, had been lost when Ayutthaya fell to Burma. Without it, the Qing court could not recognize him as king. The new governor Yang Jingsu reported that Zhen Zhao had restored the country, defeated many Burmese, and returned Chinese captives, showing loyalty to the Qing emperor.Foreign conflicts and dynastic usurpations were common, but Zhen Zhao’s case was distinct because he was of Guangdong origin. Initially, the emperor could not recognize him as king. However, the emperor repeatedly instructed the Guangzhou authorities that if Zhen Zhao requested a special title, they should report it immediately so that the emperor could grant the seal. When Zhen Zhao sent another request, Yang Jingsu drafted a report but did not submit it directly to the emperor, which displeased the court.

Conflicts among foreigners, including the overthrow of thrones, were common, but the case of Siam was different because Zhen Zhao was of Guangdong descent. At first, the Qing emperor could not recognize him as king. Later, the emperor sent several instructions to Guangzhou, stating that if Zhen Zhao requested a special imperial seal again, it should be reported immediately to the capital so the seal could be granted. This time, Zhen Zhao sent another petition, but instead of reporting directly to the emperor, Yang Jingsu submitted an old draft, which displeased the emperor.

Therefore, on July 24, the emperor sent an official named Gong Aowei to deliver the imperial edict to Yang Jingsu, reprimanding him for failing to take note of the actions of previous governors, as he should have reviewed their records. The emperor appointed Gong Aowei to assist Yang Jingsu in drafting and copying the report, while the original copy was entrusted to the Thai envoy to present to the Qing court. The letter stated that, in the spring, Li Siyiao had been transferred to govern Yunnan and Guangzhou and reported that the previous Thai king had died during the war, and that Zhen Zhao had helped restore Siam. Zhen Zhao was highly respected by the Thai people, and although he was not the crown prince, he was able to control and govern the country. He had made every effort to gain the trust of the Qing emperor. In the future, if Zhen Zhao wished to request that Guangzhou report to the emperor on his behalf, the governor would consider it and follow previous protocols. Zhen Zhao was now invited and allowed to send tribute. Once the tribute arrived, Guangzhou would immediately report to the emperor. When it was clear that Zhen Zhao sought the emperor’s support to govern the country, Guangzhou recognized that he desired a special imperial appointment, though he did not state it explicitly. If Zhen Zhao prepared tribute, sent envoys and officials, and explained the succession of the previous Thai king, Guangzhou would willingly submit the report. This letter was delivered to the Thai envoy Phraya Suay Thuan Yapha Nathu on August 6, along with gifts of food and silk. Chinese officials from Nanhai accompanied the envoy to the ship returning to Siam on August 10.

According to the Gongting Zaji (Imperial Court Annals), in the 11th month of the 42nd year (1777 CE, BE 2320), Siam sent envoys to China to request a Chinese princess in marriage. However, cross-checking both Thai and Chinese records reveals no evidence of this request. When Zhen Zhao sent envoys in 2311 BE, it was to request a special title from the emperor. The envoys explained that if Zhen Zhao received the special title, he could faithfully serve the emperor, unify the Siamese people, and prepare to attack Fu Silu, Lu Kuan, and Gao Liao, while ensuring loyalty to China. Without the imperial seal, Zhen Zhao’s claim to kingship would lack legitimacy, and neighboring states would not recognize him.

In the 42nd year of Qianlong’s reign, the Siamese envoy Phraya Suai Thuan Yaphai Natthu reported that Zhen Zhao had avenged the previous king and should gain authority through the emperor’s recognition. By sending tribute, he would be accepted by neighboring states and strengthen military power against enemies. Zhen Zhao’s efforts aimed to unify the Thai people, maintain a strong army in Southeast Asia, and avoid unnecessary conflicts with neighbors, while securing the emperor’s recognition. This demonstrates that Zhen Zhao’s repeated tribute missions were motivated by political strategy.

When the Siamese envoy reached the Chinese court, he was received according to protocol. The Chinese court prepared reciprocal gifts for the envoy to return to Zhen Zhao. Nevertheless, Zhen Zhao still had not received an official title from China.

Details of Siam’s Diplomatic Contact with China in 2321 BE (1781 CE)

On February 21, 2321 BE (Year 43 of the Qianlong reign), Yang Jingsu was transferred to govern the Fujian and Chejiang provinces, and Li Sihying temporarily became governor of Guangdong-Guangxi. On May 1, Gui Ling received his official appointment as governor of Guangdong-Guangxi and arrived on May 8. Li Sihying handed over the matter of Siam’s tribute to Gui Ling. On May 3, Gui Ling received a letter from Zhen Zhao asking when Siam would send tribute to China. Gui Ling became angry and considered sending a reprimanding letter to Zhen Zhao.

On August 18, the Qianlong Emperor sent a letter to Gui Ling, stating that he agreed with Gui Ling’s plan to reprimand Zhen Zhao, but noted that Gui Ling’s draft contained excessive rules. The Emperor recognized that Zhen Zhao had tried to report multiple times and, although China might not fully understand his intentions, he was loyal. Therefore, the Emperor advised that China should communicate politely and not be overly harsh. Reprimand should only apply when letters were sent previously without an official envoy, but via ordinary officials on merchant ships. The Emperor instructed Gui Ling to reply that the letter had been received and that he understood Zhen Zhao’s request to delay the tribute. This delay was due to Siam’s ongoing war with Burma, but it contradicted Zhen Zhao’s earlier message that tribute was ready. The Emperor still did not fully understand Zhen Zhao’s true intentions. Gui Ling sent this reply to Zhen Zhao on September 3, 2321.