King Taksin the Great

Chapter 10: Military Duties of King Taksin

Somdet Phra Chao Taksin the Great carried out military affairs with three principal resolutions:

1. Suppressing the various factions within the country that arose when Ayutthaya fell to the Burmese. The important Thai towns had set themselves up as independent powers and had to be subdued in order to unite the realm into a single kingdom.

2. Defending the kingdom, as further warfare was certain to occur because external enemies had not yet been decisively driven off.

3. Extending royal authority by enlarging the kingdom and expanding Thai power throughout the Indochinese peninsula.

10.1 Which factions did King Taksin suppress?

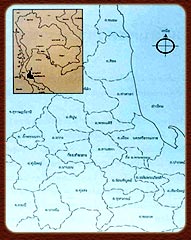

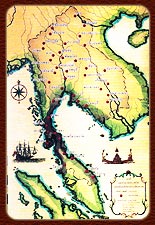

A map showing the locations of the influential factions in the early Thonburi period

(from the book Useful Facts about Thonburi)

The suppression of the four factions to unify the nation

To rebuild the Thai kingdom into a solid whole, it was necessary to suppress the various factions. Although King Taksin was at a disadvantage compared with the other groups, having no territory of his own (his base was then at Chanthaburi) and lacking the rank of a prince or a prominent noble, he nevertheless held the advantage of being in his prime, quick in both determination and thought.

10.1.1 How did King Taksin plan to unify the various factions?

At first, King Taksin of Thonburi intended to attack the strongest faction before the others, hoping that if he could defeat the most powerful group, the weaker ones would fear him and accept his authority without resistance. However, events did not unfold as expected. Therefore, he later changed his royal policy, choosing instead to gather the weaker factions first in order to strengthen his own forces, and then return to subdue the stronger faction.

The process of unification

Step 1: Marching to suppress the faction of Chaophraya Phitsanulok (Rueang) In 1768, King Taksin of Thonburi led his forces with the intention of subduing the faction of Chaophraya Phitsanulok. When he reached Koei Chai in the Nakhon Sawan region, his troops clashed with those of Chaophraya Phitsanulok. King Taksin was shot in the left shin and therefore ordered a retreat. Chaophraya Phitsanulok then proclaimed himself king, but after about seven days he developed an abscess in his throat (Prasert Na Nakhon, 1991: 22) and died. His brother, Phra Inthaarak, succeeded him, but not long after, the ruler of Phang brought his army down to attack, and Phra Inthaarak was executed at Phitsanulok (Useful Facts about Thonburi, 2000: 141).

Step 2: Marching to suppress the Phimai faction In 1768, after King Taksin the Great had firmly established his capital, he aimed to suppress the Phimai faction. He first led his forces to attack Nakhon Ratchasima and won a decisive victory. When the ruler of Phimai learned of this, he avoided battle and fled with his family and followers toward the territory of the Kingdom of Sri Sattana Khanahut, but Khun Chana, an official of Nakhon Ratchasima, captured him and presented him to King Taksin. The ruler of Phimai, also known as Krom Muen Thepphiphit, was executed, while Khun Chana was rewarded with the title Phraya Kamphaeng Songkhram and became governor of Nakhon Ratchasima (Useful Facts about Thonburi, 2000: 132–133).

Step 3: Suppressing the Nakhon Si Thammarat faction. In 1769, King Taksin of Thonburi led both land and naval forces to subdue the Nakhon Si Thammarat faction. The ruler realized he could not resist the royal army and fled with his family and followers to Pattani, but was captured by Phraya Pattani and sent back to the new ruler of Nakhon Si Thammarat, Chao Nara Suriyawong. Later, King Taksin wished to bring the former ruler to Thonburi for judgment. Upon arrival, the king pardoned him and granted him the oath of loyalty to serve as an official, along with a residence. The former ruler, known as Chao Nakhon Si Thammarat (Nu), offered his daughter, Chim, as a court lady.

By the end of 1776, Chao Nara Suriyawong, who ruled Nakhon Si Thammarat, passed away, and King Taksin graciously allowed Chao Nakhon (Nu) to return to govern Nakhon Si Thammarat, bestowing the title of a vassal prince as ruler of Nakhon Si Thammarat.

Note: By 1785, during the reign of King Rama I, the former ruler faced multiple accusations from Chao Phat, his son-in-law. King Phutthayotfa Chulalok summoned him to clarify the charges. The former ruler lost the case and requested to serve in Bangkok, where he remained for nearly a year before passing away. Chao Phat was then appointed as the new ruler of Nakhon Si Thammarat.

Step 4: Suppressing the Chao Phraya Fang faction. After Ayutthaya fell to the Burmese, Maha Rueang gathered people from several cities and declared himself ruler, adopting red robes instead of ordination garments, and became known as Chao Phraya Fang, forming a major northern faction. In 1768, learning of Chao Phraya Phitsanulok’s death and Phra Intharakorn’s succession, he marched to attack Phitsanulok, aided by locals opposed to Phra Intharakorn, capturing the city successfully, executing Phra Intharakorn, seizing property and weapons, and relocating people to Fang.

In 1770, Chao Phraya Fang’s misconduct increased, involving excessive drinking and immoral acts despite still being in monk’s robes. Rogue monks who served as commanders plundered local villagers. When King Taksin learned of this, he ordered a military campaign. Chao Phraya Fang fought for three days but fled with his followers and a newborn white elephant. The Thonburi forces captured only the white elephant, while Chao Phraya Fang disappeared.

“Mom Ratchawong Sumnachat Sawasdikul remarked on King Taksin the Great’s skill in suppressing various factions in the work “King of Thonburi” and in the journal “Mahawitthayalai,” volume 15, issue 2, 1937, stating

“The wisdom and ability of King Taksin in fully restoring Ayutthaya to independence is highly commendable. When considering the king’s position compared to other powerful figures of the same era, it is clear that King Taksin had the least advantage in saving the nation. Chao Phraya Phitsanulok had a strong and established base with solid military forces. Chao Phraya Fang enjoyed great popular support because he was believed to possess magical powers. The ruler of Nakhon Si Thammarat was both strong and skilled, capable of maintaining independence without relying on anyone. Chao Phimai belonged to a royal lineage and was highly respected by the people for his merit and extraordinary abilities. Phraya Na Kong (called Sukyi by the Burmese, meaning commander, which the Thais adopted as the name Suki) and Chao Thong In, referred to in chronicles as Nai Boonsong, were backed by Burmese forces. King Taksin alone had the lowest status, commanding only five hundred soldiers with a single firearm, without a permanent residence, forced to move from place to place under extreme hardship.

His decision to establish a base in Chanthaburi was not according to his original plan but compelled by necessity. Unlike others, King Taksin had to rely entirely on his own ability and intelligence, aided by youthful vigor and administrative skill.”

“Major General Luang Wichitwathakan wrote about the suppression of the remaining four factions—Chao Phraya Phitsanulok, Chao Phraya Fang, Nakhon Si Thammarat, and Phimai—in the book “Siam and Suvarnabhumi” (Praphat Trinarong: Thai Journal 20(72): October – December 1999: 16), stating

“He suppressed each faction one by one with the assistance of two heroes, King Phutthayotfa Chulalok and Krom Phra Ratchawang Bowon (Chao Phraya Surasi). Within a period of three years, all the factions were subdued, and Siam was reunited into a single kingdom in 1770, restoring the kingdom to a consolidated state once again.”

10.2 What royal duties did King Taksin the Great carry out in protecting the kingdom?

The protection of the kingdom included waging war against Burma and eliminating Burmese influence entirely from Lanna.

10.2.1 War with Burma, After restoring Ayutthaya, the first and most important royal duty of King Taksin was to protect the kingdom from Burmese threats. Following his victory against the Burmese at the Pho Sam Ton camp in November 1767, Siam fought the Burmese nine more times during King Taksin’s reign, as detailed below.

First War: The Battle of Bang Kung | Year of the Pig 1767

When King Taksin recaptured Ayutthaya from the enemy (during the attack on Pho Sam Ton camp, Sukyi Phraya Na Kong was killed in the battle), his reputation spread widely, and his honor was recognized as the one capable of saving the Thai kingdom from Burma. King Taksin established his base in Thonburi and conducted the coronation ceremony in the Year of the Pig 1767. All major and minor cities rejoiced, and many people submitted to him, including foreign traders such as the Chinese, who acknowledged him as the ruler of Siam.

After his coronation and proclamation as king of Ayutthaya in the ancient royal tradition, King Taksin rewarded generals and officials for their merit. At that time, Nai Sud Chinda was appointed as Chief Minister in charge of the police department. He then invited Luang Yok Krabat, the elder brother from Ratchaburi (who later became King Phutthayotfa Chulalok of the Chakri dynasty), to serve in the royal administration, and he was appointed as Phra Waring, Chief of the Police Department.

The administration of all cities, as recorded in the Royal Chronicles, states that after King Taksin’s coronation, he appointed officials to govern all major and minor cities. However, according to the chronicles, only a few cities had enough population remaining to be quickly organized into functioning cities. Counting the cities mentioned, the northern cities included Ayutthaya, Lopburi, and Ang Thong; the eastern cities included Chachoengsao, Chonburi, Rayong, Chanthaburi, and Trat; the western cities included Nakhon Chai Si, Samut Songkhram, and Phetchaburi. These 11 cities were the ones with sufficient population to establish functioning administrations, yet it was necessary to appoint governors as before throughout all cities.

In each city, King Taksin stationed soldiers in various locations. The chronicles mention that Chinese troops were assigned to establish a camp at Bang Kung in Samut Songkhram, near Ratchaburi. It is believed that similar forces were stationed elsewhere, though not specifically recorded.

When King Taksin recaptured Ayutthaya, the ruler of Vientiane, who had aligned with Burma at that time, reported to King Ava that he had learned that King Taksin had established himself as ruler and restored Ayutthaya as the capital. At that time, King Ava was concerned about potential war with China and did not consider the situation in Siam to be significant, noting that the country had been devastated and the population greatly reduced. He merely instructed Maung Ki Ma Ya, the governor of Tavoy, to send forces to inspect Siam and suppress any uprising.

At that time, Kanchanaburi and Ratchaburi along the Burmese invasion route were still abandoned. Burmese warships remained at Sai Yok, and the Burmese fortifications along the riverbank in Ratchaburi had not yet been dismantled. Phraya Tavoy advanced his army at will. When he reached Bang Kung and saw the Chinese troops of King Taksin stationed there, he ordered his forces to surround them. King Taksin commanded Phra Maha Mantri to lead the vanguard while he led the main army to Samut Songkhram and attacked the enemy. Seeing that he could not continue to fight, Phraya Tavoy withdrew his forces back to Tavoy. At the Chao Khwao checkpoint (located in Ratchaburi along the Pa Chi River), the Thai army captured all Burmese warships as well as a large amount of weapons and provisions.

The Second War: Burmese Attack on Sawankhalok | Year of the Tiger 1770

This war occurred when King Taksin expanded the kingdom’s territory up to the Burmese frontier in the north. He had recovered all former Ayutthaya territories within his realm, except for Tanaw Sri and Mergui, which remained under Burmese control, along with Cambodia and Malay states still holding semi-independent status. King Taksin resided in the northern cities throughout the rainy season, persuading the dispersed population to return to their original homes and surveying the total number of northern inhabitants. Phitsanulok had 15,000 people, Sawankhalok 7,000, Phichai (including Sawangkhaburi) 9,000, Sukhothai 5,000, and Kamphaeng Phet and Nakhon Sawan slightly over 3,000 each.

He then appointed officials who had distinguished themselves in the campaign: Phraya Yommarat (Krom Phra Ratchawang Bowon Maha Surasinghanat) as Chao Phraya Surasi Phitsanuwathirat to govern Phitsanulok; Phraya Phichai Racha as Chao Phraya to govern Sawankhalok; Phraya Siharaj Dechochai as Phraya Phichai; Phraya Tha Yai Nam as Phraya Sukhothai; Phraya Surabodin of Chainat as Phraya Kamphaeng Phet; and Phraya Anurak Phuthorn as Phraya Nakhon Sawan. He also appointed Phraya Aphaironrit (later Rama I of Rattanakosin) as Phraya Yommarat and head of the Ministry of Interior, replacing the Samuhakarn who had been removed for weakness in war. After organizing the northern cities, he returned to Thonburi.

At that time, Burma still controlled Chiang Mai. King Ava appointed Aphai Kamani, promoted to Pomayungwan, as ruler of Chiang Mai from the old capital. When the Thonburi army advanced to attack Sawangkhaburi, some of Chao Phraya Fang’s followers fled to seek Burmese protection in Chiang Mai. Pomayungwan took the opportunity to extend his territory southward, as the local population of Sawangkhaburi had allied with him. He then sent an army to attack Sawankhalok in the third month of the Year of the Tiger 1770. At that time, Chao Phraya Phichai Racha had only recently taken up residence in Sawankhalok, less than three months, and his forces were still small. However, the city had strong fortifications built long ago. Chao Phraya Phichai Racha defended the city and requested reinforcements from neighboring cities. The Burmese army sent to attack Sawankhalok was led by Chiang Mai’s commander, mostly composed of local conscripts under Burmese supervision. Seeing that the locals of Sawankhalok resisted, they laid siege to the city. When Chao Phraya Surasi, Phraya Phichai, and Phraya Sukhothai arrived with reinforcements and attacked from both sides, the Burmese forces were completely defeated and fled. In this campaign, the Thonburi army suffered no significant hardship.

The Third War: The First Thai Attack on Chiang Mai | Year of the Rabbit 1771

The reason King Taksin launched this campaign against Chiang Mai was based on his consideration that the Burmese forces in Chiang Mai were not very strong, and the Ava Kingdom was engaged in conflict with China and could not send reinforcements. The Burmese in Chiang Mai had only recently separated from Sawankhalok and were still fearful. If the army advanced promptly, it might be possible to capture Chiang Mai. Moreover, the forces for the campaign, including both the royal army and provincial troops, were already assembled. Even if Chiang Mai could not be taken, the campaign would still weaken the Burmese and provide valuable knowledge of the terrain for future planning. It was likely due to this reasoning that he led the army to attack Chiang Mai in the early months of the Year of the Rabbit 1771.

Ruins of the fortress and city walls within Chiang Mai (original) which have now been preserved

(Image from Daily News; www.chiangmaihandicrafts.com/. ../wallandmoat.htm)

The army of King Taksin of Thonburi marched to attack Chiang Mai this time, assembling troops at Phichai, totaling 15,000 men. Chaophraya Surasi was appointed as the vanguard commander, while the king himself led the main army. They advanced to Lamphun without difficulty. Seeing the enemy move swiftly, Phomayungwan did not engage in open battle but merely set up forces outside the city. Chaophraya Surasi’s army attacked and broke that camp, forcing Phomayungwan to withdraw into the city and strengthen its fortifications. The Thonburi army then laid siege to the city and raided it once, fighting through the night from 3 a.m. until dawn. Unable to enter the city, they had to withdraw. King Taksin said that Chiang Mai’s fortifications were strong and ordered a retreat. According to tradition, any king attacking Chiang Mai for the first time would likely fail and only succeed on a second attempt, which may have influenced King Taksin’s decision to withdraw.

Seeing the Thonburi army retreat, Phomayungwan sent forces to pursue. The Burmese attempted to ambush the rear troops, causing confusion, but when they reached the main army, King Taksin personally led the rear guard and engaged in combat with his sword. The troops fought fiercely until the enemy could not withstand them and fled. King Taksin then returned to the royal vessel at Phichai and sailed down to the capital. (For details, see section 10.2.2: Eliminating Burmese influence from Lanna Thailand.)

War 4: First Burmese attack on Phichai | Year of the Dragon, B.E. 2315

The next two wars (4th and 5th) were minor skirmishes. They occurred because the Burmese commanders were arrogant, not because Burma intended a large-scale war. In the Year of the Rabbit, B.E. 2314, in the Lan Xang region, Prince Suriyawong of Luang Prabang clashed with Prince Bunsan of Vientiane. Luang Prabang sent troops to attack Vientiane. Vientiane appealed to King Ava for reinforcements, so the Ava king sent Chikchingbo as vanguard and Posuphla as commander. Learning this, the Luang Prabang forces retreated to defend their city. Posuphla’s troops moved to attack Luang Prabang.

He then advanced toward northern Siam. In trying to show his military prowess over Phomayungwan, the ruler of Chiang Mai, Posuphla divided the Burmese forces: Chikchingbo as vanguard would attack Siam at the frontier. Chikchingbo captured Lablae (modern Uttaradit Province) without resistance. As Burmese resources and captives were insufficient, he advanced to attack Phichai during the dry season at the end of the Year of the Dragon. At that time, Phichai’s forces were small. Chaophraya Phichai defended the city and requested reinforcements from Phitsanulok. Chaophraya Surasi quickly raised troops and marched to Phichai. The Burmese set up a camp at Wat Eka. The Phitsanulok forces attacked it, while Chaophraya Phichai attacked from the other side. After fierce fighting, the Burmese were defeated and fled to Chiang Mai.

This war is not mentioned in the Burmese chronicles. According to the Royal Chronicles, Posuphla himself led the campaign. Chaophraya Damrong Rachanuphap analyzed the battle and considered it minor; the main Burmese army likely did not participate. Posuphla later led another expedition, which will be described further.

War 5: Second Burmese attack on Phichai | Year of the Snake, B.E. 2316

At the beginning of the Year of the Snake, factions in Vientiane quarreled. One side requested support from Posuphla. He sent an army to suppress the dispute, staying through the rainy season. Suspecting Prince Bunsan of Vientiane, he forced the prince to send children and senior officials as hostages to Ava. After the rainy season, Posuphla returned and advanced to attack Phichai.

Posuphla’s attack likely had two reasons.

The First reason, he sought intelligence from Ava regarding King Mangkra’s planned offensive against Thonburi. Second, he wished to test the Thai troops at Phichai, believing his forces, having conquered Luang Prabang, would be able to challenge them.

The second reason may have been that Posuphla felt humiliated when his troops had fled from Phichai in the Year of the Dragon, so he came to redeem himself.

According to the Royal Chronicles, after the rainy season of B.E. 2316, Posuphla again advanced his army toward Phichai. This time, the Thai forces were prepared. Chaophraya Surasi and Phaya Phichai set an ambush along the route. When the Burmese army arrived, the Thai forces attacked and scattered Posuphla’s army on Tuesday, the 7th waning day of the second month, Year of the Snake, B.E. 2316. In this battle, Phaya Phichai fought with a two-handed sword, striking down the Burmese until his sword broke. From then on, he was famously known as “Phaya Phichai the Broken Sword.”

War 6: Second Thai attack on Chiang Mai | Year of the Horse, B.E. 2317

King Taksin decided to continue the campaign. Upon learning that the Mon were rebelling against the Burmese and that the rebellion had grown serious, he realized the Burmese would have to suppress the Mon and could not yet send troops to attack Siam. He saw an opportunity to strike Chiang Mai and weaken the Burmese. The army moved through Kamphaeng Phet and assembled at Ban Ra-nga (the present site of Tak). News then arrived that King Ava had sent Ahsah Wun-kee as the main commander to suppress the Mon rebels who had attacked Rangoon. The Mon forces were defeated and fled from the Burmese. King Taksin then ordered Chaophraya Chakri (later Rama I) to lead the northern forces against Chiang Mai alongside Chaophraya Surasi. The main army would wait at Tak for news from Martaban. Chaophraya Chakri and Chaophraya Surasi advanced toward Nakhon Lampang.

When Chaophraya Chakri reached Nakhon Lampang, King Taksin remained at Ban Ra-nga. Mon refugees fleeing the Burmese arrived via the Tak checkpoint. Khun Inthakiri, the local officer, brought forward the cook, Siming Su-hrai, for questioning. The king learned that the Mon had been defeated by the Burmese at Rangoon and were retreating, moving families into Siam in large numbers. King Taksin realized that the Chiang Mai campaign was timely and ordered the army from Thonburi to station an ambush at Tha Din Daeng to intercept the Mon entering via Chedi Sam Ong, assigning Phaya Kamhaeng…

Vichit commanded the army stationed at Ban Ra-nga to intercept the Mon families entering via the Tak checkpoint from another route. He then led the main army from Ban Ra-nga in the fifth waning day of the first month, Year of the Horse, B.E. 2317, following Chaophraya Chakri’s forces toward Chiang Mai.

Chaophraya Chakri’s army advanced from Nakhon Lampang to Lamphun, where they encountered the Burmese army entrenched along the old Ping River north of Lamphun. The Burmese camp was attacked and heavy fighting ensued for several days. When the royal army reached Lamphun, Chaophraya Chakri, Chaophraya Surasi, and Chaophraya Sawankhalok defeated the Burmese, who fled back to Chiang Mai. The main army remained stationed at Lamphun, while Chaophraya Chakri’s forces continued to lay siege to Chiang Mai.

Posuphla and Pomayungwan, the Burmese commanders defending Chiang Mai, saw the Thai army encamping around the city. They sent troops out to harass the Thai camp repeatedly, but were repelled and suffered heavy casualties each time, forcing them to retreat back into the city. Meanwhile, many residents of Chiang Mai who had hidden in the forests joined the Thai forces, and those remaining in the city fled to join them in large numbers.

The White Elephant Gate was rebuilt once again between B.E. 2509–2512. Tha Phae Gate was reconstructed in B.E. 2528–2529 by the Chiang Mai Municipality and the Fine Arts Department, based on historical and archaeological evidence, along with photographic records.

(Image from the book Seen: Architectural Forms of Northern Siam and Old Siamese Fortifications)

On Saturday, the 3rd day of the waxing moon in the second month, King Taksin led the royal army from Lamphun and encamped at the royal camp by the river near Chiang Mai. He inspected the camps surrounding Chiang Mai, intending to expedite the capture of the city. On that day, Chao Phraya Chakri attacked the Burmese camps outside the city on the southern and western sides, defeating them completely. Chao Phraya Surasi also attacked three Burmese camps outside the eastern side at Tha Phae Gate. That night, Po Supla and Po Ma Yuanguan abandoned Chiang Mai, evacuating the people through the White Elephant Gate to the north, facing Chao Phraya Sawankhalok.

Since the encirclement of the city was not yet complete, the Thai forces broke through, pursued the enemy, recovered many families, and inflicted heavy casualties on the Burmese.

The next day, Sunday, the 4th day of the waxing moon in the second month, King Taksin entered Chiang Mai with the royal procession. Upon securing Chiang Mai, news from Tak reported that another Burmese force was advancing following the Mon families. King Taksin ordered Chao Phraya Chakri to manage the city, while he himself stayed in Chiang Mai for seven days before returning with the royal army to Tak.

Chao Phraya Chakri oversaw the city, sending envoys to persuade the people and households to return to their original homes. The local people of Lanna, who had been under Burmese control, submitted willingly without the need for force. Chao Phraya Chakri also convinced the prince of Nan to pledge allegiance, bringing the cities of Chiang Mai, Lamphun, Lampang, Nan, and Phrae back under the Siamese kingdom at that time. (For details, see 10.2.2)

War 7: Battle at Bang Kaeo, Ratchaburi (Thailand besieges the Burmese, causing their troops to start starving) | Year of the Horse, 2317 BE

King Taksin returned from Chiang Mai to the capital. Upon arrival, he received news that the Burmese army had advanced via the Three Pagodas Pass and attacked the forces of Phra Yai Yomrach Khaek, who had been stationed at Tha Din Daeng, causing them to retreat to Pak Phraek (present-day Kanchanaburi). At that time, the royal army that had followed him to attack Chiang Mai was still returning by boat and had not yet reached Thonburi. King Taksin therefore ordered the rapid conscription of troops in the capital. Prince Chui, his son, and Phraya Thibetsaradee were assigned to lead 3,000 men to defend Ratchaburi, while Chao Ramlak, his nephew, led an additional 1,000 men as reinforcements. Orders were also given for the northern army to advance and to hasten the troops still en route to join quickly.

According to the Burmese chronicles, A-Za Hwon-ki sent Ngui Akong Hwon (also called Chab Phya Kong Bo or Chab Kung Bo) to invade Thailand, intending only to capture the Mon families and, if unsuccessful, to retreat. Confident from previous victories over the Thai, Ngui Akong Hwon advanced to Pak Phraek after Phra Yai Yomrach Khaek’s forces were defeated at Tha Din Daeng. Phra Yai Yomrach Khaek abandoned the camp and regrouped at Dong Rang Nong Khao. Seeing the Thai not resisting, Ngui Akong Hwon split his forces into two groups: one under Mong Jaiik to encamp at Pak Phraek and plunder the provinces of

Kanchanaburi, Suphanburi, and Nakhon Chaisi, while the other plundered Ratchaburi, Samut Songkhram, and Phetchaburi under Ngui Akong Hwon’s direct command. Upon reaching Bang Kaeo, they learned that Thai forces had positioned themselves in Ratchaburi, so Ngui Akong Hwon established three fortified camps at Bang Kaeo.

Prince Chui, stationed in Ratchaburi, learned of the Burmese camps at Bang Kaeo. Confident in their ability to fight and with reinforcements from the capital approaching, he advanced to Khok Kratai in Thung Thammasen, approximately 80 sen (7.8 km) from the Burmese camps. He instructed Luang Maha Thep to lead the vanguard to set up a camp to block the Burmese from the west, while Chao Ramlak’s troops established a camp to encircle from the east. He then sent word back to the capital.

King Taksin ordered Phraya Phichai Aisawan to defend Nakhon Chaisi, while he personally led the army to Ratchaburi to inspect the camps surrounding the Burmese at Bang Kaeo. After studying the terrain, he commanded his generals to establish additional camps to fully encircle the Burmese. He also instructed Chao Phraya Inthraphai to secure the swamp at Khao Chua Pruan, which the enemy used to keep elephants, horses, and other transport, as well as for supplying their provisions. Phraya Ramanyawong was assigned to lead the Mon forces to guard the swamp at Khao Changum, located along the northern supply route of the enemy, about 120 sen (11.7 km) away.

Seeing that the Thai forces had established strong encirclements, Ngui Akong Hwon attempted to raid Chao Phraya Inthraphai’s camp one night. The Thai forces repelled him, and the Burmese tried again three times that same night but were defeated each time. Many Burmese were killed, and others captured. Observing the Thai strength, Ngui Akong Hwon requested reinforcements from the forces at Pak Phraek, prompting A-Za Hwon-ki to send Mong Jaiid to support him. (A-Za Hwon-ki remained at Mottama and, seeing Ngui Akong Hwon absent, followed him, arriving at Pak Phraek just as the news reached him.)

Chao Phraya Chakri returned from Chiang Mai to assist. The Burmese were besieged for a long time, running low on food, and heavy Thai gunfire caused substantial casualties. Eventually, the Burmese commander surrendered to King Taksin. Meanwhile, A-Za Hwon-ki had returned to Mottama. With the capture of the Burmese camp at Bang Kaeo secured, King Taksin ordered Chao Phraya Chakri to attack the camp at Khao Changum. At midnight, the Burmese at Khao Changum executed a stealth maneuver (known as Vhilarn—gradually advancing toward the Thai camp to launch a sudden all-around assault, as described by Samak Chai Komin in 2543 BE:10) to raid the Thai camp at Phra Maha Songkhram, intending to assist their comrades at Bang Kaeo. This time the Burmese fought more fiercely than before, likely having learned that the Bang Kaeo camp was close to falling. They set fire to Phra Maha Songkhram, but Chao Phraya Chakri intervened in time, recaptured the camp, and forced the Burmese back. During the night, the Burmese at Khao Changum abandoned their camp and retreated north, pursued by Thai forces with heavy casualties inflicted. The Burmese generals fled to Pak Phraek. Recognizing the total defeat of the Burmese, Takkhang Mornong (the Thai commander at Pak Phraek) did not engage further and withdrew to A-Za Hwon-ki at Mottama. King Taksin then ordered the Thai army to pursue the fleeing Burmese to the edges of the kingdom and subsequently return to the capital. Rewards and promotions were granted to all generals and officers, both senior and junior, in recognition of their contributions to the victory.

The Battle of Bang Kaeo serves as an important example of the strategy of confronting enemy forces outside the capital during the Thonburi period, encompassing both offensive (offensive strategy) and defensive (defensive strategy). The significance of this battle might seem less prominent if one follows the assumption made by Somdet Phra Krom Phraya Damrong Rachanuphap in Thai-Rob-Pama that the Bang Kaeo engagement was merely a minor encounter, arising as a consequence of pursuing the Mon families who had fled into Thai territory under Ngui Akong Hwon, particularly the supreme commander

A-Za Hwon-ki. He had no intention of waging a protracted war against Thailand, as he had not yet received orders from King Mangra to invade Thai cities.

However, it is noteworthy that both Thai and Burmese sources consistently confirm that, in fact, the Burmese demonstrated a clear determination to engage in battle directly with Thai forces. The clash was not merely incidental or a byproduct of pursuing the Mon refugees.

Map illustrating the encirclement of the Burmese at Bang Kaeo, B.E. 2317

(Image from the book Somdet Phra Chao Taksin Maharat)

The royal chronicles in the Phra Ratcha Hatthaleika edition record that King Mangra even sent officials to urge Alaung Hpone Kyaw’s army, then stationed at Mottama, to pursue the Mon rebels and invade Thai territory. Alaung Hpone Kyaw accordingly organized his forces, both the vanguard and the support army, with the vanguard attacking the Thai forces positioned at Thadin Daeng.

Burmese sources, such as the Anwa accounts, state that in the year 1136, Alaung Hpone Kyaw led the army to attack Ayutthaya. The vanguard reached Ratchaburi, and the Thai forces encircled them. Similarly, the Ho Kaew Chronicle and the Konbaung Dynasty Chronicle explicitly record that King Mangra commanded Alaung Hpone Kyaw to invade Thailand and achieve a decisive victory.

Thus, the Battle of Bang Kaeo should be regarded as a major engagement, not merely a minor skirmish intended to capture Burmese troops who had followed the fleeing Mon, or to seize plunder and captives at will.

Thai and Burmese sources both confirm that the main objective of the Burmese commanders in the Battle of Bang Kaeo was to capture Ratchaburi. Therefore, Ratchaburi was a strategically crucial point in the battle. However, this does not mean that the city’s military strategic importance emerged only during the Battle of Bang Kaeo. Its significance had been evident since the Alawun Pya campaign (B.E. 2303), resulting from the rerouting of Burmese army movements along the Thawai route, which required them to advance via Phetchaburi, Ratchaburi, and Suphanburi. This rerouting effectively made Ratchaburi a strategic gateway.

Nevertheless, the city’s importance was not merely as a waypoint among other cities. From the perspective of Thai and Burmese military strategists, Ratchaburi was a key strategic fortress, serving as the “last line of defense” before enemy forces could penetrate the central power of the Thai state. Historical evidence shows that Ratchaburi was used as a defensive stronghold against Burmese attacks since the Alawun Pya campaign. During the Fall of Ayutthaya in B.E. 2310, Thai forces advanced to block Mang Maha Naratha’s army approaching from the south at Ratchaburi. Once captured, the city became a base for splitting forces to attack Ayutthaya along two axes:

One force blocked the western cities, including Kanchanaburi and Suphanburi.

Another force blocked the southern approach to Ayutthaya, targeting Thonburi and Nonthaburi.

Ratchaburi’s strategic military importance increased during the Thonburi period, even though the Burmese had shifted their route to the Phra Chedi Sam Ong pass. The heightened importance was also due to internal Thai adjustments. As Sri Sakra Vallipodom observed, during the Thonburi and Rattanakosin periods, the kingdom’s capital moved south to Thonburi and Bangkok, below Ayutthaya. This changed army routes: to attack Bangkok (or Thonburi), forces no longer needed to pass through Kanchanaburi, Phanom Thuan, Suphanburi, and Ang Thong. Instead, the route could pass Kanchanaburi down to Ratchaburi and Nakhon Pathom, then to Thonburi—accessible by land or by waterways, particularly via the Khlong Noi river to Pak Phraek and then along the Mae Klong to Ratchaburi.

Hence, the offensive and defensive strategy against the Burmese in the Thonburi era shifted from the traditional focus on the capital. Victory depended on control over strategic locations in key provinces rather than solely defending the royal city.

In the case of the Battle of Bang Kaeo, the decisive factor was control and defense of Ratchaburi. It was therefore unsurprising that King Taksin acted rapidly and decisively to secure the city as a base of operations.

Chronicles record that upon learning of a Burmese advance via the Phra Chedi Sam Ong pass, the king commanded Prince Chui, with Phraya Thibethdi, to lead 3,000 troops to set up a camp at Ratchaburi, and additionally ordered Chao Ram Laks to take 1,000 troops as reinforcements.

One force — while the main army that had accompanied His Majesty to attack Chiang Mai and was returning by river to the capital — was ordered to send police boats to fetch them: “Do not allow anyone to stop at a house on the way. Whoever stops at a house shall be executed.” When the vessel carrying Prince Chui, his son, and Phraya Thibethdi with all the officials hurriedly arrived in front of the royal pavilion, after paying respects they were waved on with the command to hurry to Ratchaburi.

It is clear that this military operation was an urgent campaign fought against time; anyone who disobeyed the royal command and caused delay would be severely punished. Records show that when Phraya Theppayotha paused his boat to call at a house, His Majesty, on learning of it, personally ordered his execution, beheading him with his own hand, and further commanded that “the police take the head and display it at the front of Wichaiprasit Fort, and the corpse be thrown into the water so that no one may imitate the act.”

The army ordered out to meet this threat included Mon contingents under Phraya Ramanyawong, as well as the forces of Chaophraya Chakri and the provincial armies from the north and east. King Taksin himself also led the main army to join the others with a force of 8,800 men, proceeding directly to the fortified camp at Ratchaburi.

On the Burmese side, Alaung Hpone Kyaw — an experienced commander — understood the strategic necessity of capturing Ratchaburi as a base before the main Thai forces could arrive. Part of his defeat at Bang Kaeo resulted from his failure to seize Ratchaburi: the vanguard he sent forward was fixed in place by Thai forces, and with the vanguard neutralized, the main army massed at Mottama found it difficult to move down to support them.

Although the Phra Chedi Sam Ong pass chosen by Alaung Hpone Kyaw provided a shorter route for striking Thonburi than other approaches, it was rugged and difficult. If the march was delayed and the opponent seized and blocked key terrain and cut supply lines, the advancing army — especially the main force with its large numbers that required wide areas for quartering troops and establishing camps — would face severe hardship.

Burmese sources reflect Alaung Hpone Kyaw’s attempts to organize a sudden attack against the Thai forces. However, internal divisions within his army caused delays. Initially, Alaung Hpone Kyaw ordered the senior commander Minye Zeya Kyaw, who commanded 3,000 royal guards, to break through the Thai positions blocking the Burmese route. Minye Zeya Kyaw refused, claiming insufficient strength. Alaung Hpone Kyaw reported this to King Mangra. Upon learning of the situation, Minye Zeya Kyaw withdrew his forces to Mottama. Alaung Hpone Kyaw then sent Thabyay Kongbo (also called Nguy Akong Hpone in Thai sources) to act in his place, but it was too late. By the time the Burmese vanguard reached Pak Phraek and Ban Bang Kaeo, the Thai forces had already established strong defensive positions at Ratchaburi.

This failure forced Alaung Hpone Kyaw to change his strategy, opting to advance along the northern route toward Phitsanulok, similar to the campaigns of King Bayinnaung and Nemyo Sithu. Strategically, the Battle of Bang Kaeo was a continuation of Alaung Hpone Kyaw’s operations. It was not only the largest and most significant battle of King Taksin’s reign but also a test of the Thai defensive strategy, which had been adapted from lessons learned during the Fall of Ayutthaya in B.E. 2310.

During the Thonburi to early Rattanakosin periods, strategically located provincial towns became decisive battlefields. Ratchaburi was one such critical town. In essence, the Battle of Bang Kaeo was a battle to seize Ratchaburi, just as Alaung Hpone Kyaw’s campaign had aimed to capture Phitsanulok.

Victory or defeat in these battles did not merely determine control over key provinces but could also decide the outcome of the war and the fate of the kingdom itself.

Sri Chollalai (pen name) in 2482, in the work Thai Must Remember, wrote in praise of King Taksin the Great.

King Taksin the Great was not only the foremost Thai warrior, but he also endeavored to show the world that Thailand was a nation of warriors who upheld the highest virtues. This was evident when the Burmese sent an army to invade through Kanchanaburi, Ratchaburi, and Nakhon Chai Si in the Year of the Horse, B.E. 2317 (the 7th year of the Thonburi period). At that time, King Taksin the Great had just returned from suppressing Chiang Mai, and by chance, His Majesty the Queen Mother was seriously ill. Nevertheless, King Taksin the Great set aside his personal concern and urgently proceeded to confront the Burmese army at Ratchaburi, because he did not wish the Burmese to trample the outskirts of the capital and bring dishonor to the Thai nation, nor did he wish the Thai people to lose heart further. After only nine days, Khun Wiset O-sot hastened to report the serious condition of the Queen Mother. Upon hearing this, King Taksin the Great declared that, since her illness was severe, she might not live to see him; yet this campaign was of great magnitude, and at this time there was no one else trustworthy to resist the enemy. Ultimately, King Taksin the Great did not return, because he was concerned for the kingdom. He persevered and contended with the Burmese army. His Majesty the Queen Mother passed away. King Taksin the Great attempted to continue the siege and blockade of the Burmese army. When there was no way for the Burmese to break out, he could have ordered a mass volley of fire into the enemy camp to kill all the Burmese, but he did not approve of such action, in order to preserve the honor of Thai warriors. When the enemy was completely unable to fight, the Thai warriors

refrained from harming them. In the end, the Burmese army exhausted its strength and submitted to fealty on March 31 of that year. Therefore, March 31 should be remembered as a highly significant day for Thai soldiers, representing the highest level of virtue, and is a day of pride and joy to recall that

- Thai soldiers place the affairs of the nation above all else, willingly sacrificing personal matters even in the face of deep grief, so long as the work of the nation is successfully accomplished.

- The Thai nation does not invade other nations. If any nation dares to invade, Thai soldiers will not allow the enemy to escape.

- Even when the enemy is completely surrounded and defenseless, Thai soldiers may fire volleys to kill, but they do not wish to harm an opponent who has no means of fighting, so as not to compromise their honor in any way.

- When the opponent submits, the Thai show care and nurture proportionate to the situation, without exhibiting resentment or hostility further.

- Every inch of Thai land stands independent because the Thai are strong warriors.”

(Praphat Trinarong,Thai Journal , vol. 20(72), October–December 1999: 18–19)

War 8: the campaign of Aza Wun Gyi against the northern cities | Year of Ma-Me, B.E. 2318

This war was even greater than any previous campaign during the Thonburi period. In this campaign, Aza Wun Gyi declared to his generals that the Thais were no longer like before, meaning that from now on Burma could not defeat Thailand. The cause of this war was that when King Taksin of Thonburi restored Thailand’s independence, Burma was engaged in a war with China. After finishing the war with China in the Year of the Tiger, B.E. 2314, the King of Ava intended to attack Thailand again. He planned to send Phosu Phla as the commander from Chiang Mai and Pa Kan Wun as the commander to advance via the Three Pagodas Pass to besiege Thonburi, just as in the previous campaign against Ayutthaya. However, both routes were blocked. The Thais had already advanced to capture Chiang Mai, and when the army at Mottama tried to move, the Mon people rebelled in great turmoil. Therefore, the plan to attack Thailand could not succeed as the King of Ava had intended.

Shwedagon Pagoda, Rangoon (Yangon)

(Image from www.trekkingthai.com/cgi-bin/webboard/generat…)

In the Year of Ma-Me, B.E. 2317, the King of Ava proceeded to place the umbrella atop the sacred relic of Shwedagon Pagoda in Rangoon. At that time, Aza Wun Gyi had already suppressed the Mon rebels, but he was still awaiting the Burmese army that had followed the Mon household to Mottama. The King of Ava, seeing that a large army was already stationed at Mottama, ordered that the plan to attack Chiang Mai should be further considered by Aza Wun Gyi.

Aza Wun Gyi returned to Mottama with the King of Ava’s orders in the fifth month of the Year of Ma-Me, B.E. 2318. When the army of Ta Khaeng Ma Nong fled from the Thais and reported the Burmese army’s defeat, the Thais captured the army of Nguyokong Wun, and another Burmese force was completely routed at Khao Changum. Ta Khaeng Ma Nong then had no choice but to retreat.

Aza Wun Gyi planned the attack on Siam following the model of King Bayinnaung of Hongsawadi: he would lead a large army to strike the northern cities to weaken Thai forces first, then hold the northern cities as strongpoints, and afterward send both land and naval forces down to attack Thonburi via the Chao Phraya River in that single approach; he then ordered a period of rest and replenishment.

The troops were stationed at Mottama, and orders were sent to Po Supla and Po Mayungwaun, who had retreated from the Thais to settle at Chiang Saen, to march back and capture Chiang Mai during the rainy season. They were also instructed to prepare warships, transport ships, and gather provisions to supply Aza Wun Gyi’s army, which would advance at the beginning of the dry season. Po Supla and Po Mayungwaun then assembled their forces and marched to attack Chiang Mai in the tenth month of the year of Ma-Me, 2318 BE.

After the victory at Bang Kaeo, Thonburi had a free period of five to ten months, during which news arrived that Po Supla and Po Mayungwaun would advance to attack Chiang Mai. King Taksin therefore issued an order to Chao Phraya Surasi to lead the northern forces to support Chiang Mai and instructed Chao Phraya Chakri to command the reinforcement army. The command was also given that if the Burmese retreated from Chiang Mai, they should continue to pursue and capture Chiang Saen.

Po Supla and Po Mayungwaun advanced their Burmese army to attack Chiang Mai ahead of the Thai forces, setting up camps nearby in preparation to assault the city. However, the forces they had assembled were not particularly strong. When news arrived that the Thai army was marching up, the Burmese retreated to Chiang Saen, avoiding further engagement.

Aza Wun Gyi prepared his main army, and by the eleventh month he dispatched Kalabo and Mang Yayangu, his younger brother, to command the vanguard from Mottama, while Aza Wun Gyi himself led the main army to reinforce. The Burmese troops marched through Mae Lamao Pass into Tak, then followed the route to Ban Dan Lan Hoi and on to Sukhothai. The vanguard set up at Ban Kong Thani by the new Yom River, while the main army rested at Sukhothai.

Chao Phraya Chakri and Chao Phraya Surasi, stationed at Chiang Mai, were preparing to march to attack Chiang Saen. When they received news that a large Burmese army was advancing through Mae Lamao Pass, they immediately returned their forces via the northern cities.

Sawanlok, Phichai City

When they arrived at Phitsanulok, the two Chao Phrayas consulted on how to confront the enemy. Chao Phraya Chakri observed that the Burmese army was very large, while the Thai forces in the north were comparatively few. He advised to defend at Phitsanulok and await reinforcements from Thonburi. Chao Phraya Surasi also wanted to strike the Burmese first, so he gathered the northern city troops and advanced to fight the Burmese at Ban Kong Thani. Chao Phraya Surasi positioned his forces at Ban Krai Pa Faek. The Burmese attacked and defeated the Phayu Sukhothai forces, then pursued them to Chao Phraya Surasi’s camp, where a battle lasted three days. Seeing that the Burmese greatly outnumbered them, they retreated back to Phitsanulok.

Alaungshwungyi divided the Burmese army to guard Sukhothai and personally led troops to Phitsanulok, establishing camps along both banks of the Chao Phraya River. The Thais organized effective city defenses. While Alaungshwungyi besieged Phitsanulok, he inspected the camps and surrounding terrain daily.

Upon learning that Alaungshwungyi had led a large army into the northern cities, the Thonburi side also received reports that another Burmese force was advancing from Tanaw Sri in the south. King Taksin, wary of a two-front threat, commanded forces to defend Phetchaburi against the southern advance. After securing the southern defense, he personally led the main army of over 12,000 men northward on Tuesday, the 11th day of the waxing moon of the second month, to confront the northern enemy.

Battle Formation Part 1

When King Taksin arrived at Nakhon Sawan, he first organized transportation routes to allow the main army to link up conveniently with Chao Phraya Chakri’s forces at Phitsanulok. He ordered Phraya Rajasethi to command the Chinese troops stationed at Nakhon Sawan to guard the supply lines and watch for enemies advancing along the Ping River. The king then led the main army up the Khwae Yai River to Pak Ping in Phitsanulok, establishing the royal camp there, as it was a key canal junction. Between the Khwae Yai River at Phitsanulok and the Yom River at Sukhothai, a day’s journey downstream, he commanded officials, generals, and officers to establish camps along both riverbanks up to Phitsanulok.

– Stage 1: Camped at Bang Sai, commanded by Phraya Rachasuphawadi

– Stage 2: Camped at Tha Rong, commanded by Chao Phraya Inthara Phai

– Stage 3: Camped at Ban Kradad, commanded by Phraya Rachaphakdi

– Stage 4: Camped at Wat Chulamanee, commanded by Chao Muen Samoechai Racha

– Stage 5: Camped at Wat Chan at the back of Phitsanulok, commanded by Phraya Nakhon Sawan

Patrol units were to be sent to monitor and secure transportation routes at every stage, and conscripted artillery units were to be prepared at the front to assist any camp quickly. Phraya Si Krailas was assigned 500 men to clear a path along the river from Pak Ping through all the camps up to Phitsanulok.

When the main army linked with the forces defending Phitsanulok, Alaungshwungyi immediately advanced to engage the Thonburi army.

According to the chronicles, after the Thai camps were established along both riverbanks as described, Alaungshwungyi positioned Burmese troops directly in front of Chao Muen Samoechai Racha at Wat Chulamanee on the west bank with three camps. Another Burmese unit moved down to scout and confront Thai forces along the west bank, fighting from Stage 3 down to Stage 1 at Bang Sai. King Taksin dispatched 30 conscripted artillery pieces to assist Phraya Rachasuphawadi in defending the camp. The Burmese fought until evening, then withdrew. On Thursday, the 12th day of the waxing moon in the 3rd month, King Taksin ordered Phra Thamtrai Lok, Phraya Rattanaphimol, and Phraya Chonburi to defend the royal camp at Pak Nam Ping, then led the main army to the east bank of Bang Sai to assist Phraya Rachasuphawadi. That evening, the Burmese attacked the west bank, targeting Chao Phraya Inthara Phai’s camp at Stage 2, Tha Rong. Fierce fighting ensued. King Taksin dispatched 200 conscripts with artillery to assist, but the Burmese failed and withdrew.

At this point, Alaungshwungyi realized that the Thai forces advancing from the south were stronger than expected. He feared that dividing the troops besieging Phitsanulok to attack the southern Thai army would allow the Chao Phrayas to counterattack from the north. Therefore, he halted the offensive against the Thonburi forces and sent instructions to the reinforcement army stationed at Sukhothai: 5,000 troops to advance and intercept the Thai supply lines, 3,000 to cut Thonburi logistics, and the remaining 2,000 to assist in the fight at Phitsanulok.

Battle Phase 2

Seeing that the Burmese army which had attacked the camps had withdrawn back toward Phitsanulok, King Taksin of Thonburi prepared to attack the Burmese forces besieging Phitsanulok. On Wednesday, the 13th day of the waxing moon in the 3rd month, he ordered Phraya Ramanyawong to lead the Mon troops through Phitsanulok city to camp close to the Burmese positions on the northern side. Chao Phraya Chakri and Chao Phraya Surasi were assigned to reinforce and establish camps close to the Burmese on the eastern side, while Phraya Nakhon Sawan, stationed at Wat Chan at the back of Phitsanulok, was to extend his flanking camps toward the Burmese on the southern side. The Burmese attacked the Mon camps, but the Mon forces fired volleys that inflicted casualties, forcing the Burmese to retreat back into their camps. The Mon established their camps successfully. The forces under Chao Phraya Chakri and Chao Phraya Surasi initially lost some camps to the Burmese but managed to recapture them and set up positions close to the Burmese across all sides. Whenever the Burmese attacked, they were repelled. The Burmese dug multiple trenches to protect themselves while attacking Thai positions, and the Thais dug connecting trenches to break through. Fierce trench battles occurred across all camps for several days, yet the Thai forces could not breach the Burmese camps.

On Tuesday, the 2nd day of the waning moon in the 3rd month, King Taksin arrived at the Wat Chan camp at 10 p.m., ordering all commanding officers at the front lines to prepare their units. At 5 a.m., the signal was given for all Thai forces to simultaneously assault the Burmese camps on the eastern side of the city. The fighting continued until morning, but the Thais could not capture the Burmese camps and had to withdraw. Alaungshwungyi, observing the Thai positions on the eastern side for several days, anticipated the attack and, with superior forces, reinforced his troops.

As the Thai assault on the Burmese camps did not succeed, the next day King Taksin summoned all commanders at the Wat Chan camp to discuss the next strategy. It was decided that Chao Phraya Chakri and Chao Phraya Surasi would combine forces and attack the Burmese camps specifically on the southwest side. Another Thai unit from the main army would flank and attack the Burmese from behind, aiming to break them through an encirclement maneuver in succession. After planning, King Taksin returned to position the main army at Tha Rong camp (Stage 2), while the camps from Pak Ping upward remained in place.

The next day he ordered the army of Phraya Nakhon Sawan, then encamped at Wat Chan, to fall back to the main royal army, and to bring up the forces of Phraya Horathibodi and the Mon troops of Phraya Klang from the Bang Sai camp, then combine them into a single army of 5,000 men with Phraya Nakhon Sawan as the vanguard. He instructed them to lie in ambush behind the Burmese camps on the western side, and if the Burmese became engaged with Chao Phraya Chakri’s forces, to strike in and envelop them; he also commanded that additional artillery from Thonburi be brought up by Phra Ratchasongkhram.

The Burmese force stationed at Sukhothai received orders, and Alaung Hpone Kyaw divided his troops and sent an army down via Kamphaeng Phet intending to cut the Thai army’s supply lines and to advance on Phitsanulok as ordered. The scouts of Phraya Sukhothai learned that the Burmese were advancing by those two routes and reported to King Taksin. The king therefore revised the deployment: he ordered Phraya Rachaphakdi and Phraya Phiphatkos, who were encamped at Ban Kradad, to move down to assist Phraya Rachasethi in defending Nakhon Sawan, and ordered Phraya Weng’s Mon contingent to join the royal main force Phakdi Songkhram and hasten to reconnoiter the enemy at Ban Lan Dok Mai in Kamphaeng Phet to learn which route the Burmese would take; if they could engage the enemy, they were to attack, otherwise to withdraw. As for the army of Phraya Maha Mantian, which had been sent to ambush and envelop the Burmese, it was to proceed, with Phraya Thamma to support with another detachment.

Chao Phraya Chakri and Chao Phraya Surasi marched out to attack the Burmese camps besieging the city on the southwest side and fought the Burmese, but they could not break the Burmese camps because the reinforcement force intended to envelop from the other direction did not arrive on schedule. The vanguard of Phraya Maha Mantian, namely Phraya Nakhon Sawan, had advanced to Ban Som Poi and become engaged with the Burmese, thus becoming fixed there. Chao Phraya Chakri and Chao Phraya Surasi therefore had to hold their fortified positions. What actions Phraya Maha Mantian’s main force took thereafter are not recorded in the Royal Chronicles; it is only noted that the army of Phraya Nakhon Sawan returned to encamp at Ban Kaek.

It is thus understood that when King Taksin saw that it was no longer possible to envelop the Burmese without being detected, he recalled both the armies of Phraya Nakhon Sawan and Phraya Maha Mantian.

Battle Phase 3

Seeing that the Thai forces which had camped along the river south of Phitsanulok had been redeployed, Alaungshwungyi ordered Kalabo to lead an army to cut off the supply lines feeding into Phitsanulok. The Burmese succeeded in raiding the supplies several times.

On Friday, the 12th day of the waning moon in the 3rd month, news arrived from Thonburi that the Burmese had advanced via the Singkhon Pass and attacked Kui and Pran cities, destroying them. Krom Khun Anuraksangkharm, defending Phetchaburi, dispatched troops to block the enemy at the narrow pass. King Taksin, fearing another Burmese advance toward Thonburi, ordered Chaophraya Prathumphaichit to lead a force back to defend the capital. The main army also withdrew accordingly.

The Mon troops under Phraya Jeng, stationed at Kamphaeng Phet to intercept the Burmese, attacked successfully when the Burmese arrived from Sukhothai unexpectedly, capturing enemy weapons. However, the Burmese forces were numerically superior, and when the rear elephant units arrived, Phraya Jeng had to retreat and hide while continuing to gather intelligence on the enemy. The Burmese force advancing toward Kamphaeng Phet was ordered by Alaungshwungyi to move against Nakhon Sawan, the Thai supply base, aiming to weaken the Thai forces aiding Phitsanulok. King Taksin, realizing the Burmese plan, ordered Phraya Ratchaphakdi and Phraya Phiphatkos to retreat and join Phraya Ratcha Setthi to defend Nakhon Sawan. When the Burmese reached Kamphaeng Phet and discovered Nakhon Sawan well-defended, they halted, established camps at Kamphaeng Phet, and sent a detachment through the western forest to bypass Nakhon Sawan toward Uthai Thani.

On Saturday, the 13th day of the waning moon in the 3rd month, King Taksin received news that the Burmese at Kamphaeng Phet had set up camps at Ban Non Sala, Ban Thalok Bat, and Ban Luang, with one detachment having raided Old Uthai Thani. Their exact movement was unknown.

On Tuesday, the 2nd day of the waxing moon in the 4th month, Phraya Rattanaphimol at the Pak Ping camp reported that Burmese scouts were clearing a position in Khlong Ping, about three bends inland. King Taksin ordered Luang Wisut Yothamat and Luang Ratchayothathep to bring eight cart-mounted cannons to reinforce the western side of Pak Ping camp. That day, the Burmese set up four camps opposite Phraya Thamma and Phraya Nakhon Sawan at Ban Kaek and began advancing to encircle.

On Wednesday, the 3rd day of the waxing moon, King Taksin personally inspected the area from Tha Rong camp to Ban Kaek, where the Burmese were establishing encircling camps. He ordered Phraya Siharatdechochai and Krom Muen Thipsena to reinforce Phraya Nakhon Sawan and then returned to Tha Rong camp. He summoned Chao Phraya Chakri to discuss military strategy. During this consultation, the Burmese attacked the Pak Ping camp. King Taksin ordered Chao Phraya Chakri to defend the main camp while he personally led the naval forces from Tha Rong to assist Pak Ping. By morning, seeing the Burmese did not advance further, he assigned Phraya Thep Arachun and Phraya Phichit Narong to manage the situation and returned to Phitsanulok.

That night, King Taksin returned to Pak Ping. At 5 a.m., the Burmese attacked the Khlong Kra Phuang camp, defended by Phraya Thamma Trilok and Phraya Rattanaphimol. The fighting continued until dawn. King Taksin crossed a pontoon bridge to the western side, directing forces to assist in the defense. Phraya Sukhothai reinforced and built connecting trenches, while the main royal troops defended. Luang Phakdisangkharm established positions near the Burmese on the Khlong Kra Phuang side, and Luang Senaphakdi led troops to attack the Burmese rear.

On Saturday, the 6th day of the waxing moon, Phraya Sukhothai, the main royal troops, and Luang Senaphakdi simultaneously attacked the Burmese camps at Khlong Kra Phuang, engaging in fierce combat with short weapons, but the Thais could not break the enemy due to the larger Burmese numbers.

On Sunday, the 7th day of the waxing moon, King Taksin ordered Chao Phraya Inthraphai, stationed at Tha Rong, and the Mon troops under Phraya Klang Mueang to move down to assist at Khlong Kra Phuang. He ordered an extension of the flanking camp by 22 sen (2.15 km). As dusk approached, the Burmese attacked the Thai positions but failed to capture them. King Taksin then summoned Phraya Yamachart from Wat Chan camp to take command and coordinate all Thai forces engaged against the Burmese at Khlong Kra Phuang.

Around Tuesday, in the fourth month on the ninth waxing day, Azaewunki ordered Kalabo to command forces to attack another Thai camp situated above Pak Phing. Kalabo advanced with his army and established a camp close to the camp of Phraya Nakhon Sawan, which stood on the western bank of the Kwae Yai River at Ban Khaek. Then, on Thursday night, Kalabo sent his troops across the river to raid the camp of Krom Saeng Nai, which was located at Wat Prik on the eastern bank. The two hundred and forty men of Krom Saeng who defended the camp were unable to withstand the Burmese assault, and the Burmese captured all five camps on the eastern side.

On Friday, in the fourth month on the twelfth waxing day, Phraya Nakhon Sawan, who was stationed at Ban Khaek, reported that the Burmese had established camps encircling down to the riverbank and had crossed over to attack the five camps at Wat Prik, all of which had fallen. Seeing that the Burmese seemed prepared to attack from the rear, he requested permission to withdraw his forces to establish positions on the eastern bank. King Taksin of Thonburi therefore ordered the royal army guarding the palace together with the astrologer-royal’s forces stationed at Khok Salut, and the army of Phraya Nakhon Chaisi stationed at Pho Prathap Chang to advance to Pak Phing. He also ordered the Mon troops of Phraya Klang Mueang and the astrologer-royal’s forces to join them, along with the forces of Phraya Thep Aratchun and Phraya Wichit Narong stationed at Tha Rong, who were combined into the army of Phraya Yommarat and sent to fight the Burmese at Wat Prik. As soon as the camps were established, Kalabo launched an assault. The Thai troops were not yet fully prepared, and the Burmese seized the camp. When Phraya Yommarat arrived with fully assembled forces, he advanced to attack the Burmese and recaptured the camp. The Burmese withdrew to their former positions, and both sides fortified themselves in continued fighting.

At that time, Azaewunki sent Mang Yae Yangu, his younger brother, to command another Burmese force to cross over and encircle the rear of the royal army at Pak Phing from the eastern side. They established several camps in close proximity to the royal army. Fighting continued for many days, but the Thais could not break the Burmese lines. King Taksin, seeing that the enemy forces were too numerous and that remaining in battle at Pak Phing would lead to disadvantage, decided on Thursday, in the fourth month on the tenth waning day, to withdraw the royal army from Pak Phing to establish a defensive position at Bang Khao Tok in the Pichit region. The government troops stationed at various points of defense also withdrew in order, following the royal army.

The fourth phase of the campaign

As for Chaophraya Chakri, after he had met with King Taksin of Thonburi and returned to Phitsanulok, he conferred with Chaophraya Surasi and agreed that it was no longer possible to defend the city, as provisions were extremely scarce. They therefore decided to prepare to abandon Phitsanulok, ordering the soldiers in the outer camps facing the Burmese to withdraw back into the city. The Burmese followed and closed in on the city walls. The defenders stationed along the battlements fired cannons in resistance. Unable to enter the city, the Burmese withdrew and positioned their artillery to exchange fire.

On Friday, in the fourth month on the eleventh waning day, the two Chaophrayas learned that the royal army had retreated since the previous day. They therefore ordered the defenders to intensify their cannon fire more than usual, and brought the piphat ensemble up onto the bastions to deceive the Burmese into believing that preparations were being made to hold the city for many more days. They then arranged the troops into three formations. When the formations were fully organized, at 9 p.m., the city gates were opened and the army marched out to attack the Burmese camps on the eastern side. The Thais broke through the Burmese camp and opened a passage. The two Chaophrayas then quickly led their troops toward Ban Mung Don Chomphu, but the civilian families who followed them were scattered—some reached the royal army at Bang Khao Tok, while others, exhausted and weary, were captured by the pursuing Burmese. The two Chaophrayas led their troops across the Banthat mountain range and regrouped their forces at Phetchabun. The Burmese continued besieging Phitsanulok for four months before finally taking the city.

Azaewunki, upon learning that the Thai army had broken through and fled, moved in and occupied Phitsanulok. Seeing that provisions were severely lacking, he dispatched two forces: one under Mang Yae Yangu to Phetchabun to gather food supplies from Phetchabun and Lom Sak for transport back, and possibly also to attack the forces of the two Chaophrayas; the other under Kalabo, ordered to move toward Kamphaeng Phet to patrol for provisions. After these forces had separated, Azaewunki received a royal order reporting that the King of Ava had died and that Jingguja, the royal prince, had ascended the throne, commanding Azaewunki to return to Ava immediately. Shocked, Azaewunki wished to send messengers to recall Mang Yae Yangu’s army but could not reach them in time. Fearing punishment if he delayed, he gathered all valuables and herded together the families they had captured, then marched his army back through Sukhothai and Tak, exiting at the Mae Lamao pass along the route they had come. He ordered Kalabo’s forces to remain in Thai territory and wait to return together with Mang Yae Yangu. For this reason, two Burmese armies were left behind, and the Thais had to continue suppressing them for many more months. The armies sent to pursue the Burmese were led by Phraya Phon Thep and Phraya Ratchaphakdi, who marched toward Phetchabun and encountered Mang Yae Yangu’s army at Ban Naim, south of Phetchabun. The Thai forces launched a concentrated attack, causing the Burmese to flee northward into Lan Chang territory and then back into Burma through Chiang Saen.

When King Taksin of Thonburi traveled to the royal camp at Chai Nat, he ordered Krom Khun Anurak Songkhram, Krom Khun Ramphubet, and Phraya Mahasena to march and attack Kalabo’s army stationed at Nakhon Sawan, and then advanced with the royal army in support. Yet for reasons unknown, on Wednesday, in the eighth month on the third waxing day, he returned to Thonburi.

The army of Krom Khun Anurak Songkhram, Krom Khun Ramphubet, and Phraya Mahasena advanced to attack the Burmese camp at Nakhon Sawan. The Burmese had established a camp of roughly more than one thousand troops. The Thai army attacked the camp, and the Burmese resisted fiercely, with fighting continuing for many days. King Taksin of Thonburi then marched with the royal army once again from Thonburi. When he arrived at Chai Nat, he received word that the Burmese had abandoned their camp at Nakhon Sawan and fled toward Uthai Thani. King Taksin therefore ordered the armies of Phraya Yommarat and Phraya Ratchasuphawadi, along with the Mon forces under Phraya Ramanwong, to join the army of Chao Anurutthewa, who had previously marched ahead, so that they might pursue and decisively defeat the Burmese. The Thai forces caught up with the Burmese at Ban Doem Bang Nang Buat in Suphanburi, engaged them in battle, and the Burmese, unable to withstand the assault, retreated toward the Three Pagodas Pass.

On Thursday, in the ninth month on the second waning day, King Taksin marched with the royal army from Chai Nat up to Tak, ordering officers to pursue the Burmese. More than three hundred were captured alive. The Burmese then fled beyond the borders of the kingdom, and so the king returned to Thonburi.

The war of Azaewunki’s northern campaign lasted from the first month of the Year of the Goat, 1775, until the tenth month of the Year of the Monkey, 1776, a span of ten months before hostilities ceased. The outcome of the war should be concluded as showing that neither side gained a decisive victory.

As for the campaign of Azaewunki in 1775–1776, the historical records remain inconsistent. Prince Damrong Rajanubhab expressed the view that neither side was victorious. Professor Khachon Sukpanich, however, presented evidence from the Glass Palace Chronicle of Burma and from the History of Burma written by Sir Arthur Phayre, the British Governor of Burma, as well as accounts recorded in memoirs. When these three additional sources presented by Professor Khachon Sukpanich are considered together, they indicate that the result of the war was not, as long believed, a stalemate. Specifically:

The Glass Palace Chronicle records that after taking Phitsanulok, Azaewunki engaged the army of King Taksin of Thonburi at Thung Song on the riverbanks. But Azaewunki then received the royal order reporting that King Hsinbyushin had died and that Jingguja (Sinkumin), the royal prince, had ascended the throne, commanding the Burmese forces to return urgently to Ava. Upon arrival, Azaewunki, despite his long-standing fame and merit dating back to his victory in the war with China, was punished and removed from his position for poor command, for allowing disorder in the army, and for ineffective military strategy against the Thais. This aligns with the evidence of Sir Arthur Phayre, who wrote:

“…When the rains ended, Maha Siyasu (Azaewunki) led his forces through the Raheng Pass and encountered only weak resistance. But internal conflict arose within the Burmese army. The deputy commander, Zeya Kyo, disagreed with the battle plan, but Maha Siyasu proceeded with it. He captured Phitsanulok and Sukhothai, yet suffered a tremendous defeat and was forced into a shameful retreat back to the frontier…Many officers were executed, and Maha Siyasu himself was stripped of rank and deeply disgraced…” The Thai memoirs record:

“…In the Year of the Dragon, Martaban fell, and Phraya Jeng fled with his people to seek royal protection. Phraya Cha Ban held his city firmly and would not come down. The king marched to attack but could not take it and withdrew to the hillside. He later marched to attack Chiang Mai and then came down again. At the end of the year, the Burmese advanced in pursuit by five routes, each of ten thousand troops. Fighting continued for three years. Phitsanulok was lost, but the Thais dug tunnels to attack the Burmese camp, which was broken. The Burmese tore down their encirclement in the fields, and a major Burmese commander was captured along with many tens of thousands of troops. The Burmese were defeated and retreated…”

These various sources show that although Azaewunki captured Phitsanulok, he was ultimately defeated by King Taksin of Thonburi (Paradee Mahakhan, 1983: 24–25).

Note: Azaewunki is a Burmese noble title. In Burmese chronicles it appears in two forms: one by official rank, Atehwunkyi, meaning Grand Minister responsible for collecting military levies, and another by court title, Hwunkyi Maha Siha Sura.

In the Thonburi period, the Burmese chronicles state that Azaewunki was an important royal-blooded Burmese commander. Earlier, in 1774, when King Hsinbyushin prepared to invade Thonburi, Mon laborers were conscripted to build roads. Dissatisfied, the Mon rose in rebellion, seized Martaban, gathered their people into a great force, captured Sittaung and Hongsawadi, and were preparing to advance on Rangoon. Azaewunki then marched to suppress them, pursuing the Mon down to Martaban, but Phraya Jeng and the Mon leaders fled into Siam through the Three Pagodas Pass.

Later, King Hsinbyushin ordered Azaewunki to plan the invasion of Siam. Azaewunki prepared his forces and divided them into two groups, advancing through Tak and pursuing the Thais as far as Sukhothai. He then attempted for a long time to capture Phitsanulok, which was at that time under the defense of Chaophraya Chakri. Azaewunki admired Chaophraya Chakri’s military skill so much that he even requested to see him. In the end, the Thais were forced to abandon the city due to a shortage of provisions, but at the same moment King Hsinbyushin died, and Prince Jingguja ascended the throne and ordered Azaewunki to withdraw his army.

The accounts of Azaewunki’s later life differ, but according to the Thai Historical Encyclopedia, after Prince Jingguja ordered Azaewunki to return, he then sought grounds to strip Azaewunki of his rank and titles.

Later, Azaewunki cooperated with Atwanhwun to overthrow King Jingguja and offered the throne to Mang Mong. But Mang Mong ruled for only eleven days before King Bodawpaya executed him. When King Bodawpaya ascended the throne, he appointed Azaewunki as Viceroy and administrator of the southern provinces, residing at Martaban until his death in 1790 (Thonburi Knowledge, 2003: 173–174). The Ninth War

The Burmese Attack on Chiang Mai in the Year of the Monkey, 1776

The cause of this war stemmed from the desire of King Jingguja, newly enthroned as King of Ava, to attack Chiang Mai, which was one of the fifty-seven cities of the Lanna domain. He assembled a Burmese-Mon army under Amlokhwun as commander, with Tawhun and Phraya U Mon as deputy commanders, marching from Burma to join the forces of Po Ma Yung Nguan, who was stationed at Chiang Saen, and together they advanced to attack Chiang Mai.

At that time, Phraya Cha Ban, whom King Taksin of Thonburi had appointed as Phraya Wichian Prakan, had governed Chiang Mai since the Thais had taken it from the Burmese. Seeing that the approaching Burmese army was too powerful to resist, he sent a report to Thonburi and then evacuated the city, fleeing with the population to Sawankhalok. When King Taksin learned that the Burmese were attacking Chiang Mai and that Phraya Wichian Prakan had abandoned the city, he ordered that Phraya Wichian Prakan be summoned to Thonburi, and he issued a royal order for Chaophraya Surasi to lead the northern provincial forces to join with Phraya Kawila, ruler of Nakhon Lampang, to march and retake Chiang Mai. When the Thai forces advanced, the Burmese were unable to resist, abandoned Chiang Mai, and retreated.

When the Burmese withdrew from Chiang Mai, King Taksin of Thonburi reflected that the city had become greatly disordered and its population scattered. It would be difficult to restore it to its former state, and there were not enough people left to defend it. If the Thai army were to withdraw and the Burmese were to return, Chiang Mai would surely be lost again. He therefore ordered the city to be abandoned. From that time onward, Chiang Mai remained deserted for more than fifteen years, until it was reestablished during the reign of King Rama I of the Rattanakosin Kingdom.

This ninth war was the last conflict between Siam and Burma during the Thonburi period (from Thai-Burmese Wars, authored by Prince Damrong Rajanubhab) (excerpted from Somdet Phra Chao Taksin Chom Badin Maha Rat, Sanan Silakon, 1988: 66–88).

10.2.2 The elimination of Burmese influence from Lanna Thai

The Lanna Thai kingdom was a territory that connected the northern Thai kingdoms with Burma, comprising Chiang Mai, Lampang, Lamphun, Phrae, and Nan, which were autonomous principalities governed by local rulers. It held strategic importance for both Thailand and Burma, with both sides competing for influence.

In order to exert influence over this region, the kingdom was at times ruled by the Burmese and at times by the Thais (Ayutthaya), depending on which side was stronger at any given period. After Chiang Mai fell to the Burmese during the reign of King Bayinnaung in 1558, there were intermittent movements within Chiang Mai to “revive the Man” (resist Burmese rule), some of which achieved temporary success during periods of internal political turmoil in Burma, such as between 1727–1763 under the leadership of Thepsing of Yuam, but the Burmese soon reconquered the region each time (Somchot Ongsakul, 2002: 1).

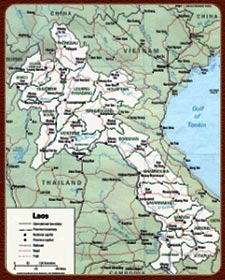

Map showing the Lanna Thai kingdom

(Image from the book Maps–Geography: Lower and Upper Secondary Level)

In the reign of King Taksin the Great, after he had unified the various provinces into a single kingdom in 1770, he led an expedition to attack Chiang Mai in order to eliminate Burmese influence completely.

It was recorded that Po Ma Yung Nguan led the Chiang Mai forces to besiege Sawankhalok in the third month of the Year of the Tiger, 1770, continuing into the fourth month of that same year. Upon learning of this, King Taksin departed from the capital to attack Chiang Mai. From the sequence of events, it can be inferred that when Phraya Phichai Racha received news that the Burmese were advancing, he must have sent a report to Thonburi. When the Burmese reached Sawankhalok, another report was likely sent immediately. This report probably reached Thonburi in the third month, at a time when King Taksin had only recently returned from his northern campaign and arrived back in the capital. The troops and logistics of the royal army were likely still assembled and not yet dispersed. Upon learning from the report that Po Ma Yung Nguan, the ruler of Chiang Mai, had personally marched south, the king became concerned, since the northern towns had only recently been subdued and their populations were not yet firmly loyal or dependable.