His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej the Great

Chapter 4: King Mahathammaracha

Upon the passing of His Majesty King Ananda Mahidol (Rama VIII) on June 9, 1946, His younger brother, Prince Bhumibol Adulyadej, acceded to the throne. On May 5, 1950, the Coronation Ceremony was held in accordance with ancient royal traditions.

From 1946 to the present (2004), a period of 58 years, His Majesty King Rama IX has reigned in full accordance with the Ten Royal Virtues of Kingship. Khun Thongtor Kluaymai Na Ayudhya wrote in Psychology of Security (1987: 47–58) as follows:

“When the Thai people migrated to the Chao Phraya River basin, they assimilated Mon culture from the Dharmasastra scriptures, which harmonized well with their own. There arose the belief that the king should be a Dhammaraja, akin to the Mahasammata Raja of the Dharmasastra, by observing the Ten Royal Virtues of Kingship (Dasavidha-Rajadhamma), practicing the Four Principles of Righteous Rule (Rajasangahavatthu), and upholding the Twelve Regal Conducts (Cakkavatti-vatta).”

1. The Ten Royal Virtues of Kingship

It is a code of virtues that predates the Buddhist era and may be regarded as a political philosophy of the Eastern world, providing a framework for those in power. Buddhist scholars later incorporated it into their own religious doctrine. His Holiness the Supreme Patriarch, Prince Vajirananavarorasa, delivered a sermon on the Ten Royal Virtues (Dasavidha-Rajadhamma) during the Coronation Ceremony of His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej on May 5, 1950. In one passage, he stated:

‘The Thai monarch must uphold the principles known as the Ten Royal Virtues, or the tenfold code of conduct for kingship, which are rooted in Buddhist teachings, as expressed in the Pali verse: …’

ทานํ สีลํ ปริจฺจาคํ

อกฺโกธํ อวิหึสญฺจ

อิจฺเจเต กุสเล ธมฺเม

ตโต เต ชายเต ปีติ

อาชฺชวํ มทฺทวํ ต ปํ

ขนฺติญฺจ อวิโรธนํ

ฐิเต ปสฺสาหิ อตฺตนิ

โสมนสฺสญฺจนปฺปกํ

May His Majesty the King, as the supreme monarch, be endowed with wisdom to discern and uphold the ten meritorious royal virtues continuously in His reign, as follows: Generosity – the act of giving; Morality – maintaining purity in body and speech, free from wrongdoing; Self-Sacrifice – the practice of charitable giving; Honesty – integrity and truthfulness; Gentleness – kindness and humility; Effort – overcoming laziness and unwholesome actions; Freedom from Anger – abstaining from anger; Non-Violence – causing no harm to others, including animals; Patience – enduring what must be endured; Non-Opposition – acting rightly, maintaining equanimity, neither swayed by pleasure nor displeasure. By practicing these ten meritorious virtues, joy and bliss naturally arise within His Majesty, as He continuously embodies these qualities.

The following will present the royal duties and achievements of His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej (Rama IX) to illustrate each of the Ten Royal Virtues.

The first royal virtue, Dana – Generosity

The royal virtue of Dana, or generosity, as exemplified by His Majesty the King, is beyond full description. His Majesty has bestowed royal funds to organizations, groups, and individuals across numerous professions and sectors, including police and military personnel who maintain national security, people in remote areas, the sick and the needy, and students. His generosity has even extended to supporting the funerals of those who have rendered distinguished service to the nation.

One of the best examples illustrating His Majesty’s generosity in a single year was the royal donation made during the charity event presided over by General Arthit Kamlang-ek, Commander-in-Chief of the Royal Thai Army and Supreme Commander, along with the management committee, on December 2, 1984. They presented themselves before His Majesty to offer 60 million baht for royal charitable purposes at Dusit Palace. On January 22, 1985, His Majesty addressed the group of attendees, and the speech, as recorded from His Majesty’s voice, includes the following excerpt:

“Regarding the funds that have been contributed, these come from donations collected throughout the country. I am deeply touched by the goodwill of everyone who has donated, whether the amount is large or small; collectively, it has become a substantial sum. I am pleased to receive these funds because the expenses for carrying out various projects are considerable. As previously reported, the development work in different projects requires significant expenditure, beyond the regular budget or ordinary operational funds. Moreover, these funds help support public health and education for both youth and adults, so that people may become beneficial members of society. Consequently, a considerable amount of money is needed. I wish to take this opportunity to express my gratitude to all of you, as well as to all donors. Those present here today represent only a portion of those involved; there are approximately six million people who have contributed to this work but cannot be present today. I extend my heartfelt thanks to all who have donated and participated, as your efforts inspire morale and foster unity.”

The King then explained that the funds donated could not be described as being “reserved for future use,” because the money previously given, including what had just been presented, had already been fully utilized. While this may seem unusual—why say it has been spent when donors wish to know how it will be used—His Majesty proceeded to provide a brief summary of expenditures.

Earlier, the Commander-in-Chief, General Arthit Kamlang-ek, read the account of the received funds. Now, His Majesty reviewed the expenditures, noting that these pertained to the year 1984, while the current year was 1985, with more than half a month already elapsed. The summary indicated how the donated funds and proceeds from the charitable event had been allocated. This included regular operational expenses, or budgeted costs, which had been fully spent, given the limited government budget. Some expenditures were covered by personal funds, eligible royal funds, and donations; although not all items could be accounted for, the purpose was to show how the funds received from across the country had been applied.

Examples of expenditures included medical supplies and healthcare costs totaling 16,886,917.02 baht for that year, royal donations for hospital and military support of 6,307,500 baht, and support for students, including book fees and allowances, amounting to 4,119,482.50 baht. Consumable goods distributed to the public totaled 8,819,166.75 baht, while supplies for police and military personnel amounted to 8,645,374 baht. Charitable contributions also covered funerals to honor individuals who had rendered distinguished service, totaling 2,616,850.50 baht.

One item listed, which may seem unusual, was the purchase of large vehicles. These vehicles were necessary for official development visits, where long convoys were required. For example, police responsible for leading the procession needed to know the number of vehicles involved to organize the route efficiently.

The traffic police, responsible for road safety during royal processions, were always informed of the convoy’s length and instructed to exercise caution. Because of the long convoys, three large, wide vehicles were purchased, along with two service vehicles for technical support. These service vehicles were used whenever repairs or emergencies arose during travel—for example, if a bridge was damaged, the service vehicles would be deployed to restore it. The total cost for these five vehicles was 2,008,367.50 baht.

Another item listed was the development of hill tribe communities, totaling 19,418,721 baht. Additionally, there were fuel costs: the regular budget provided fuel for routine operations, but during provincial visits, especially with long convoys and multiple daily assignments, special fuel expenditures were required. These costs, which amounted to several hundred thousand or even millions of baht, were not included in the report, possibly to avoid overemphasizing donations. The total of the items listed amounted to 72,297,944.90 baht, indicating that there was still a shortfall remaining.

The second royal virtue, Sila – Observance of Morality

His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej, as a devout Buddhist, not only observed the precepts appropriate to various occasions but also followed ancient traditions. Notably, He entered the monkhood on October 22, 1956. On this occasion, His Majesty delivered a speech on October 18, 1956, which included the following excerpt:

“Since Buddhism is the national religion of our country, and in accordance with my own faith and conviction, I regard it as a good and worthy religion, based on its truths and reasonable teachings. I have therefore thought that, if the opportunity arises, I should enter the monkhood for a period of time according to royal tradition, which is also a way to honor and repay the merits of my royal ancestors in accordance with customary practice.”

Since I ascended the throne following the passing of the Supreme King, more than ten years have elapsed, and I have felt that it is now the appropriate time to fulfill the intention I once held. Moreover, the recent recovery of the Supreme Patriarch from illness brought me great joy. I reflected that, if the Supreme Patriarch could serve as my preceptor during my ordination, it would also be a fitting expression of my respect and devotion to him. Therefore, I decided to enter the monkhood on the 22nd of this month.

It is noteworthy that the Thai monarch traditionally serves as a moral teacher, instructing the people in the Dhamma, a practice that can be traced back to King Ramkhamhaeng of Sukhothai. In analyzing the royal conduct, which reflects moral principles, one must refer to royal speeches and guidance.

It is well recognized that morality (Sila) is inseparable from the Dhamma. Sila represents prohibitions, while Dhamma represents proper conduct. Moral principles sustain the world and illuminate the path of life. His Majesty has consistently promoted these moral principles. In his speech at the Thammasat University commencement ceremony on November 21, 1957, he stated:

“An ‘ideal’ is a mental image or conception of supreme goodness and beauty in any aspect. If realized, it is considered supremely good and beautiful. Generally, humans naturally desire to encounter goodness and beauty, and thus everyone should have ideals. Yet these ideals must not cause harm to others, and must consider the welfare of others or the public. If such pursuit of excellence is undertaken solely for one’s own benefit, causing detriment to others, it cannot be considered a true ideal. The creation of an ideal takes time; for some, it begins in youth, while for others, it emerges later in life. Those who have undergone proper education should adopt and uphold ideals when performing future actions. Critically, one must choose ideals grounded in moral principles, both in thought and practice, rather than uncritically following the ideals of others. If everyone holds such noble ideals and acts sincerely with regard to the true welfare of the public, I believe it will contribute to the happiness and prosperity of the nation, which in turn benefits each individual. Even if a nation were to decline or perish, how could personal happiness be achieved?”

In his commencement address to the students of the College of Education on December 13, 1962, His Majesty the King stated:

“…Human beings, in a sense, are one species among all creatures, yet there are many differences. The most important is knowledge. Other creatures, trained by their parents, only learn the basic ways of living as animals or rely on their instincts. Humans, however, in addition to natural knowledge, possess intellect that enables them to seek and transmit knowledge from their ancestors. There are numerous texts documenting various disciplines and moral customs for future generations to learn. This intellect is crucial and must be applied rightly, in accordance with these texts and ancient moral traditions. If intellect is used improperly and without morality, humans can become worse than animals…”

In his commencement address to the students of the College of Education on December 15, 1960, His Majesty said:

“…A teacher must not only possess academic knowledge or teaching skills. One must also train students in morality and culture, instilling a sense of responsibility for their duties and as good citizens of the nation. Knowledge or teaching involves imparting information to students, whereas training (discipline) shapes the mind and heart of the learner until it becomes habitual. Therefore, do not merely teach; train the students so they acquire both knowledge and proper character…”

Morality (Sila) is the first of the threefold training, which includes Sila, Samadhi (concentration), and Panna (wisdom). Only those who possess Sila can develop Samadhi, and only those with Samadhi can attain wisdom. His Majesty the King has fully embodied Sila, maintaining unwavering concentration in performing royal duties and demonstrating profound wisdom in analyzing and solving problems. Morality steadies the body, speech, and mind; a steady mind brings joy and insight in all matters. This can clearly be observed in His Majesty’s royal conduct, which serves as a model for all Thais.

The third royal virtue, Pariccakam – Practice of Sacrifice

Her Royal Highness Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn summarized the concept of the Ten Royal Virtues in comparison with the Ten Perfections (Paramis) in Theravada Buddhism in her royal composition The Ten Perfections in Theravada Buddhism, regarding Pariccakam (sacrifice) as follows:

“Pariccakam is similar to Dana (generosity). While Dana refers to giving aimed at benefiting the recipient, Pariccakam refers to self-sacrifice, such as relinquishing personal benefits or happiness. A monarch or ruler should practice moral principles in all their duties for the welfare of the people. Therefore, one must set aside attachment to personal interests. This is akin to the perfection of giving (dana parami), but with a different purpose. Examining each of the Ten Royal Virtues reveals that they share the same characteristics as the Ten Perfections described in Buddhism.”

All of His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej’s royal duties, carried out without yielding to fatigue or hardship, exemplify self-sacrifice or great generosity (mahapariccaka) in accordance with Buddhist principles. When undertaking official visits to the people—considered a primary royal duty—He traveled formally to inspect projects initiated by royal initiatives and presided over ceremonies as invited by the provinces. Such visits were undertaken only when circumstances permitted.

The reporting of news by newspapers to promote goodness for the public is also considered a form of self-sacrifice. This virtue can be applied to individuals and various events. His Majesty emphasized this in a royal address to the board of the Thai Newspaper Association at Chitralada Royal Villa on July 25, 1972, stating:

“…Journalists and all newspapers, those involved in conveying news and opinions to the public, have another important duty: to foster good understanding within the country and among the people, and to provide useful information to the public. If news and articles are presented constructively, they contribute to the prosperity and stability of the nation. Thus, the role of newspapers is both extensive and important. Newspapers are said to be a force in the country; if this force is used for good, it will benefit the nation, but if used improperly, it can lead to decline. It is difficult to specify exactly what constitutes misuse, but generally, actions intended for constructive purposes are good. However, if such intentions serve only a part of society or nature without regard for harm to others, it is considered improper conduct. Therefore, with this power, newspapers must exercise caution, careful judgment, and some degree of self-sacrifice for the public good…”

Among the Ten Royal Virtues, while Pariccakam—sacrifice—is more abstract than Dana, which involves giving material things, it stands out most prominently when analyzing royal conduct. It is directly related to the people. All royal duties, great and small, carried out for the welfare of the Thai people without yielding to fatigue or hardship, exemplify Pariccakam—self-sacrifice. This aspect of His Majesty’s conduct allowed the Thai monarch to deeply understand the hearts of the people and distinguished Him as a ruler admired worldwide.

The fourth royal virtue, Acchava – Practice of Honesty

Her Royal Highness Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn explained the meaning of Acchava in her royal composition The Ten Perfections in Theravada Buddhism as follows:

“Acchava is the quality of being upright and honest, not engaging in deceit or hidden manipulation. In a community, if people do not act with integrity in their duties and are not honest with one another, conflicts arise, and a peaceful society cannot be maintained.

A monarch must possess an upright disposition, being straightforward and honest toward the people, without intending to deceive or harm anyone.”

His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej, as the Head of State, was the unifying heart of the Thai nation, bringing together all groups in harmony. He remained impartial, adhering to the principles of the Brahmavihara, sharing both the hardships and joys of his people. His Majesty displayed honesty and integrity toward all individuals and groups, without showing bias or favoritism. As a constitutional monarch, He performed all royal duties fully, earning the deep respect and veneration of the entire populace.

His Majesty was more than a king; He was not only the head of state as understood by the international community but also a leader in community development. He treated all his subjects equally, whether in Bangkok or in remote rural areas, such as hill tribe communities in distant regions.

King Bhumibol Adulyadej consistently shared in the joys and sufferings of his people, dedicating most of His time to visiting and supporting them, regardless of social status or background.

Throughout the kingdom, His Majesty traveled extensively to serve the nation and religion, particularly to remote areas where government assistance had yet to reach. Even in regions that were difficult to access, requiring travel over many kilometers, He never wavered or grew weary. As Queen Sirikit once remarked regarding royal visits to the people:

“…The King and I are not satisfied with merely visiting the people or performing traditional ceremonial duties. We must strive to do better. We must assist the government in improving the well-being of the populace, for we are a developing country. Merely visiting the people as a formality because it is expected of the Head of State is meaningless. If we cannot participate in alleviating the hardships of our people, then being the Head of State would be considered a failure…”

As a devout Buddhist, His Majesty fully carried out his duties while also serving as the Supreme Patron of all religions, fostering harmony and cooperation among various faith communities. This was grounded in the royal virtue of Acchava—uprightness and honesty.

Moreover, the judiciary, which issues judgments in His Majesty’s name, is widely recognized by the public as fair and impartial. Even the judges themselves are respected as exemplifying Acchava, practicing honesty and integrity in their roles.

The fifth royal virtue, Mattava – Gentleness

The royal virtue of Mattava refers to His Majesty’s gentle and kind disposition. He showed proper respect to elders, gentleness toward peers and those of lower status, and maintained consistency in his conduct without harshness or disdain toward others. Photographs of His Majesty during royal visits, when paying respects to senior monks at various temples, left a lasting impression on all who witnessed them. Examples include images of Him paying homage to Luang Pu Waen Sujinno at Wat Doi Mae Pang in Chiang Mai and carefully assisting Luang Pu Toh at Wat Pradoochimplee in Bangkok after a royal ceremony at the palace.

One remarkable instance is that two Thai kings visited the Pope, the spiritual leader of Christians worldwide, at the Vatican, demonstrating the royal virtue of Mattava – gentleness. For example, when His Majesty King Chulalongkorn first toured Europe in 1897, He paid a visit to the Pope. As a devout Buddhist, He found a way to show the utmost respect to the Pope with grace and propriety. This is recorded in a royal letter addressed to Somdet Phra Maha Samana Chao Krom Phraya Vajirayanawongse, in which it is noted:

“… I must confess one thing regarding kissing the Pope’s hand. Please understand that my intention was only to kiss the hand of an elderly person, for Westerners sometimes kiss the feet… But in truth, the Pope is an elder worthy of reverence, and his conduct is righteous, embodying moderation and simplicity …”

Later, when His Majesty the King made a state visit to Western countries in 1960, he went to pay respects to Pope John XXIII, the head of the Vatican City and the Roman Catholic Church. Her Majesty the Queen Mother recorded the events of that day in her royal memoir, Memories of Accompanying State Visits Abroad, stating…

“… When the Pope extended his hand, His Majesty the King bowed in respect and took his hand. Later, he told me that the Pope reached out to prevent him from bowing too low. We both thought this was due to the Pope’s kindness, not wanting us to do anything that might conflict with the rules of our own faith. As for me, when he offered his hand, I presented a lotus stem to him in reverence. While holding his hand, we both observed that, besides his age, he possessed qualities respected by people worldwide. Our Lord Buddha has taught us that honoring those worthy of respect brings great merit …”

The sixth royal virtue, Tapa – Practice of Austerity

Her Royal Highness Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn explains the meaning of Tapa in her royal writing “The Ten Perfections in Theravada Buddhism” as follows:

Her Royal Highness Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn explains Tapa (ascetic practice or perseverance) as follows:

“Tapa, when used to refer to perseverance, means the determination to eliminate laziness and negligence, focusing on performing duties that are right and proper. In Brahmanical tradition, a king’s tapa involves protecting the people. Therefore, a king who possesses tapa will be revered and respected by all. When people gather as a group, everyone must know their responsibilities. The king must act with diligence and not be idle, comparable to the perfection of effort (viriya paramita).”

In the context of viriya, Tapa reflects the king’s tireless diligence in carrying out both minor and major royal duties. Thai monarchs, across all eras, have consistently shown deep concern for their subjects, fostering mutual trust and cooperation between the ruler and the people. This harmonious relationship facilitates effective governance and strengthens national unity. Moreover, Thai kings have exercised their royal authority with compassion, never seeking to monopolize power for themselves. For example, King Chulalongkorn (Rama V) carried out extensive reforms to modernize the nation for the welfare and prosperity of the people, despite fully understanding his supreme authority. As he explained to his officials:

“… The royal power of the King of Siam is not written in any law because it is absolute, beyond the ability of anyone or anything to obstruct. Yet in reality, whatever the king does must follow what is proper and just… For instance, the title ‘Lord of Life’ implies the power to take a life without wrongdoing. While this is legally possible, it has never been exercised.”

This illustrates how perseverance, coupled with moral restraint, guided the king in serving his people with dedication, fairness, and compassion.

Another excerpt of His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej’s royal instruction, given to His Royal Highness Crown Prince Maha Vajiralongkorn, illustrates the principle of tapa (ascetic perseverance) in the exercise of kingship:

“… To be a king is not for wealth, not for controlling people at one’s whim, not for revenge, nor for living in ease and comfort. If one desires that, there are two paths: ordination as a monk or wealth. A king, however, must be a servant to the people, restraining himself from pleasure and pain, from love and hatred that may arise in the heart or be stirred by others. He must be diligent without laziness. The results of such perseverance are reputation and recognition after death as one who preserved the dynasty and protected the welfare of the people under his rule. One must keep these two as the foremost purpose, above all else. Those who cannot adopt this mindset cannot understand how to govern a kingdom effectively…”

These royal instructions, together with the earlier declaration by King Chulalongkorn (Rama V), demonstrate the depth of compassion and benevolence (maha-karuna) that Thai monarchs have historically extended to their people. The documents serve as historical evidence that the hearts of the Thai kings—those who were the sovereigns and protectors of the people—have always been devoted to the welfare of their subjects.

From past to present, Thai kings of the Chakri dynasty have shown unwavering generosity, wisdom, and dedication in serving their people. King Bhumibol Adulyadej, as the direct successor of this lineage, faithfully continued this tradition. What is truly remarkable is the vast extent of His Majesty’s compassion and care for his people, which goes far beyond ordinary human capability. Even in times of peace, His Majesty remained deeply attentive to the well-being of every citizen, ensuring that the nation thrived in harmony and prosperity.

Whenever suffering arose, even in remote and perilous regions, His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej tirelessly visited the people, providing material aid to alleviate hardship. Through His boundless compassion, He inspired the people to endure adversity. In times when the nation faced threats, He remained deeply concerned for the well-being of citizens, soldiers, police, and volunteers, personally overcoming danger to offer encouragement. Such royal conduct left a lasting and profound impression on all who witnessed it.

His extraordinary dedication, foregoing personal comfort and pleasure to serve the welfare of the Thai people, exemplifies the immeasurable depth of His Majesty’s benevolence. Those close to the royal presence unanimously attest to His unwavering resolve to ensure peace and prosperity for His people. His conversations with attendants and officials focused almost entirely on the welfare of the populace: understanding why people suffered, how suffering could be alleviated, and how happiness could be increased. This steadfast commitment radiated throughout the royal household, influencing Her Majesty the Queen, the royal children and grandchildren, the extended royal family, as well as civil, military, and police officials.

All royal initiatives, whether at the Chitralada Royal Residence, the Grand Palace, Klai Kangwon Palace, or Phuping Palace, were directed toward the relief of suffering and the promotion of well-being for people near and far.

The magnitude of His Majesty’s benevolence toward his subjects is beyond description. During His 58-year reign, His leadership—through both official duties and personal engagement—brought the nation to unprecedented prosperity and ensured the welfare and peace of people throughout the kingdom, making Him a protective and guiding presence for all.

The account presented above illustrates the taba (ascetic perseverance) virtue in the aspect of diligence and steadfast effort, which His Majesty the King exemplified. Due to the interconnectedness of the royal virtues in relation to His Majesty’s conduct and royal duties, this type of dedication also becomes clearly evident in the Kanti (patience/endurance) virtue. Only a monarch possessing exceptional Kanti could consistently perform such arduous duties over time, demonstrating unwavering commitment and resilience.

The seventh royal virtue, Akkotha – Not showing anger, was perfectly exemplified by His Majesty King Rama IX. Even those close aides and palace officials who served intimately under His Majesty for decades never witnessed any display of wrath, harshness, or temper. His Majesty’s composure and patience in all matters reflected the highest standard of Akkotha, demonstrating self-control and serene leadership.

The seventh royal virtue, Akkoṭha – Not showing anger, was clearly tested during His Majesty King Rama IX’s state visit to Australia in 1962 (B.E. 2505). While attending the ceremony to receive an honorary Doctor of Laws degree at the University of Melbourne, His Majesty faced a challenge from a group of radical students who misunderstood both His Majesty and Thailand. Some held signs with defamatory messages, while others shouted mockingly, disrespecting His Majesty and the honor of the Thai nation.

Her Majesty the Queen vividly described the incident in her memoir, “Memories of Accompanying the King on Official Overseas Visits”, noting the calm and composed demeanor of His Majesty despite the provocation, demonstrating the true essence of Akkoṭha—complete restraint from anger in the face of offense.

Then it was time for His Majesty to deliver his speech through the loudspeakers on the stage. Before anything could begin, a group of intellectuals outside started jeering and laughing. I felt a chill in my hands and a fluttering in my heart, feeling so much compassion for His Majesty that I did not know what to do and dared not even look up at his face. Eventually, I forced myself to glance up to offer moral support, but it was I who received encouragement instead, for I saw him walking to the center of the stage with a calm face. Immediately, everyone in the auditorium clapped loudly, as if to give him strength. When the applause subsided, I looked up again and saw His Majesty opening the robe he wore with his academic gown, then gracefully bowed to the noisy group outside. His face showed a slight smile, his eyes a faint twinkle of amusement, but his voice remained steady and calm.

He simply said, “Thank you all very much for the warm and courteous welcome you have shown to your foreign guest,” then turned to continue speaking to the audience inside the hall. I almost laughed aloud with satisfaction, for the jeering outside stopped instantly, as if a switch had been turned off, and after that, everything remained calm. Everyone, both outside and inside, sat quietly, listening and contemplating his words. I thought his speech that day was excellent, delivered extemporaneously without any notes. He spoke of Thailand’s ancient culture, our independence, our unique language, and the alphabet we invented. We have had our own legal system granting rights and freedoms to our people for over 700 years. I almost laughed at this point because after saying “over 700 years,” he seemed to suddenly realize, startled slightly, and politely bowed as he added, “I forgot, Australia did not exist back then.” He then continued, saying that Thai people have always been generous, willing to give others a chance, and open to listening to opinions, because we usually think carefully and reason things out before making decisions, never acting impulsively without logic.

As a result of this remarkable display of wisdom and composure in delivering his speech under such circumstances, when the ceremony concluded, the attendees came forward to pay their respects and praise his words. Even the group of students who had initially reacted disrespectfully changed completely. Some looked blank or embarrassed, avoiding his gaze and no longer acting strangely, while others graciously smiled, waved, and applauded the royal couple all the way to their car.

The eighth royal virtue, Avihisa, is the practice of non-violence.

Avihisa, in its general meaning, is the principle of not causing harm to others. It is expressed through the four divine abidings: loving-kindness, compassion, sympathetic joy, and equanimity, which were abundantly present in the royal mind of His Majesty King Rama IX.

The principle of non-harm toward one another arises from the moral training received from religion, which also implies non-harm between different faiths. This was expressed in the royal address on the occasion of Pope John Paul II’s audience during his visit to Thailand at the Chakri Maha Prasat Throne Hall on Thursday, May 10, 1984, as follows:

“The reason Thailand and the Thai people have always welcomed religious missionaries with friendship and sincerity is that Thai Buddhists possess a steadfast moral conscience and compassion, recognizing that all religions teach goodness and encourage individuals to act rightly, appropriately, and beneficially, seeking peace and clarity in life. Moreover, we have customs and norms for showing respect to followers of other religions, extending kindness and sincerity without disparaging or harming people of different nationalities or faiths, as such behavior would lead to discord and suffering. Consequently, Christianity has flourished in this country, and Thais have come to know and deeply respect the Pope, the head of the Catholic Church, as a significant figure who spreads peace, serenity, and enlightenment to people worldwide.

When I had the opportunity to visit the Vatican in 1960 (B.E. 2503), Pope John XXIII inquired about how devoutly the Thai people practiced their religion.

I replied that the Thai people are all good religious followers, most of whom practice Buddhism as the national religion, while others follow various faiths, because our people enjoy freedom and equality both under the law and through customary practice in religious observance. The Pope expressed great admiration and joy to me that Thailand has citizens of good moral character who uphold righteousness and integrity as their guiding principles.

During His Holiness’s visit to Thailand, Your Excellency must have clearly observed that Christians in this country practice their faith diligently and peacefully. You would also have noticed that the Thai people are willing and happy to pay respect to Your Excellency as the head of a religion, one devoted to peace, compassion, and serene purity. I believe that friendship, benevolence, and sincere mutual support among all religious followers will be a powerful and sacred factor to uphold peace, freedom, liberty, and equality for all humankind.”

The virtue of non-harm and fostering love and harmony among people is expressed as unity. This unity has been a key force that has kept Thailand peaceful and able to safeguard the nation without falling under anyone’s domination, thanks to King Rama IX as the central pillar whom everyone follows in this virtue. A unique feature of Thai monarchs is that they hold the role of father to the people, teaching and guiding them in virtue, like a parent instructs a child or a teacher guides a student, with compassion. Therefore, this royal conduct is particularly evident in the Thai monarchy. History records that ancient Thai kings placed bells at palace gates so that people with troubles or grievances could ring them and present their complaints directly to the monarch. Even today, those in distress may submit petitions to the King at any time. In some cases, even after lower, appellate, and supreme courts have made decisions, the convicted still retain the right to petition the King, all through the power of royal benevolence and the practice of non-harming (avihimsa).

Moreover, if we analyze the royal conduct of avihimsa, or non-harming, in comparison with the ten royal virtues, it can be seen that the King’s practice of charity and donations was intended to assist his subjects, guiding them to uphold righteousness and practice only proper livelihoods, to share justly what they rightfully earn for the benefit of others, particularly fellow countrymen. He observed moral precepts to control himself from harming others, remaining free from the ten unwholesome deeds, maintaining calmness in body, speech, and mind, and serving as a model for his people. He practiced the virtue of self-discipline (tapas) with firm diligence, overcoming corruption and wrongdoings as a royal benevolence for his subjects, while also mastering himself to remain steadfast in social and ethical duties as well as the four divine abodes. When these were accompanied by avihimsa, anger did not arise within him; even when anger occasionally flared, he subdued it through the virtue of patience, with a serene and radiant countenance, becoming beloved and respected by all people. In summary, this was because he did not depart from virtue—that is, he remained firmly established in unshakable moral principles.

The ninth royal virtue, Khanti, is the practice of patience.

Her Royal Highness Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn explains the meaning of Khanti in her work “The Ten Perfections in Theravada Buddhism” as follows:

Khanti, in the context of the ten royal virtues, refers to the conduct of enduring greed, anger, and delusion without expressing harmful words or actions driven by these defilements. It also entails patience in the face of suffering and tolerance toward unpleasant or offensive speech. A monarch must possess a courageous heart, capable of maintaining calmness and composure in mind, body, and speech, in order to govern the people so that they may live in happiness.

In summary, Khanti means patience in body, speech, and mind. In the physical sense, it is seen in enduring duties and restraining oneself from fatigue or hardship. In Buddhism, Khanti is considered a supreme virtue. This is why His Majesty King Rama IX was able to accomplish all royal duties successfully, remaining undaunted by hardship, largely through the practice of this virtue.

During a discussion on “Our King,” organized by the Thai Government Scholarship Association, Office of the Civil Service Commission, on Saturday, May 16, 1987, Police Lieutenant General Wasit Dechkunjorn spoke about the royal duties in one part of his talk:

The first thing that impressed me, and still does to this day, was the King’s genuine concern for the well-being of people across the entire country, regardless of where they lived or what profession they had. We often hear publicity that His Majesty visits hilltribes on this mountain or that hill, but that is just one image—and perhaps one that has been overly publicized—because pictures of our King and the royal family taken with hilltribe people in their distinctive attire and ornaments sell well.

However, other images that we did not see at the time, but now see more frequently than before, are those of the King with ordinary citizens, which I observed throughout the more than ten years I served close to the royal court. These images come directly from the King’s genuine concern for his people.

From the first day I had the opportunity to sit at the royal table, I heard the King’s words directed to those at the table, and I never heard anything else but matters concerning the people: who they are, where they live, and what they do. When the discussion concerned royal visits, it was about where to go, how to go, and what to do.

On my first time following the royal tours, I realized immediately that the King’s royal duties were truly carried out for the people, and they involved a complex process. His Majesty personally visited the citizens, as some of you may have seen on television films showing the King driving himself. Television cameras could capture only the moments during the visits themselves.

But what the cameras could not capture, and thus could not show you, were the preparations by the advance staff who organized the visits. We only see the moments when the King is with the people. We do not see the preparations, and after the visits, the events that followed are also unseen, because no one had the opportunity to record or compile them for public knowledge.

Before the royal departure, plans were made in advance regarding where His Majesty would visit. These plans were based on pre-gathered information about which communities were in distress or in need of special attention. These locations were selected by officials from the Royal Secretariat, together with the Royal Guard Department, royal police, and civil authorities. The advance plans marked specific points of visitation, but they could be changed at any time.

During the royal visits, the officials responsible for the advance arrangements were those familiar with the King and aware of his interests. Therefore, these knowledgeable officials had to be ready to provide information on these matters as needed.

All of this was a broad framework set up before the actual events, which could be altered or supplemented at any moment according to the King’s discretion.

Once His Majesty arrived, as many of you may know from newspapers, radio, or television, both our King and the Queen did not rush, but spent ample time with the people. It was therefore completely natural that visits starting in the afternoon could extend into the night or late evening, depending on how many people were present and the amount of time spent discussing their well-being.

After returning from the visit, the true work or royal duties began. The assistance or royal patronage granted to the people commenced after the visits and continued indefinitely, without end.

Finally, and to allow others to share as well, one lasting impression for me personally was the King’s steadfast composure in crises. During my service close to the royal court, I witnessed at least two clear examples of his unshakable presence of mind.

The first instance was on October 14, 1973, which many of you here may recall as a time of crisis in Thailand so severe that the constitution did not specify how a new government should be formed. At that time, those in power in the country were filled with anxiety, discouragement, and fear, to the point that many felt Thailand was approaching disaster. Our King, His Majesty Rama IX, however, did not share in the fear of others. During the events outside Chitralada Royal Villa, while people were clashing violently, His Majesty continuously considered how to resolve the situation. Many of you may remember that the crisis was quickly brought under control, and Professor Sanya was appointed as Prime Minister, even if temporarily, as acting head.

Eventually, a new assembly was established, a new constitution was drafted, and a new government was formed, only to be replaced later as you all know.

In truth, I am not speaking lightly when I say that if it were not for this King, Thailand might have faced consequences that we would not have witnessed today. But because we have continuity and institutions that support the nation through every government transition, past or future, the changes have been bearable for Thais. The result, as we see today, is the survival of Thailand.

In terms of speech, our King has never displayed any harsh or violent words toward anyone. Only royal guidance and admonitions rooted in righteousness have been given to his subjects. Professor Pavas Bunnag has often remarked that the King never spoke ill of anyone or placed blame on others, which stems from his dharmic forbearance, the ability to restrain and calm his speech.

The royal virtue that acts as an enemy to anger—rage or wrath—and the harmful thoughts associated with it, are absent in His Majesty’s disposition. Such tendencies are controlled through moral discipline, restraint, and moderation, as previously illustrated. As for controlling delusion or ignorance, this is accomplished through adherence to right practice, attentive listening, and discussion of the Dharma. At the same time, these teachings are conveyed to his subjects through royal admonitions and addresses to various audiences. Ultimately, the manifestation of His Majesty’s forbearance is the dignity, respect, and calmness that command the eternal reverence of the people.

The tenth royal virtue, Avirodhana, is the practice of flexibility and adaptability.

What deserves special consideration is the last royal virtue, Avirodhana. The Pali term “Virodhana,” transliterated into Thai as “Phirodh,” means anger. If Avirodhana were translated simply as “non-anger,” it would overlap with Akkodha, making it redundant. Avirodhana therefore carries another meaning, which, according to the Pali-English dictionary by Childers, is conciliation—flexibility, adaptability, and the fostering of harmony and unity. This may be the most important of the ten royal virtues. Political science also supports this view, noting that since the monarch remains politically neutral, not favoring any political party or individual, the greatest benefit the king can provide to the nation—and which few others can achieve—is the promotion of national unity. Naturally, political interests may cause divisions among parties or competition among key figures in the country, but the king, being respected and revered by all sides and trusted to prioritize the nation’s welfare above all, can mediate conflicts, leading all parties to compromise and reconcile under his guidance.

In Thailand, on 14 October 1973, student centers led the people in protests demanding the promulgation of a constitution. This resulted in riots, including the burning of government offices such as the Government Lottery Office, the Anti-Corruption and Tax Evasion Office, and the Metropolitan Police Headquarters at Phan Fa. The government deployed the military to suppress the unrest, leading to numerous deaths and a situation that threatened to escalate into widespread bloodshed.

His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej (Rama IX) used his royal authority, compassion, wisdom, and the loyalty of the people to resolve the crisis. He appeared on radio and television to deliver speeches that reminded and comforted all parties. In one address, he stated:

“…I urge all parties and individuals to halt acts of violence, to restrain themselves, so that the nation may quickly return to normalcy…”

He also cautioned the government against harming the people:

“…I request that the government refrain from harming students, university students, and the people, under any circumstances. Even if government officials are provoked or even attacked first with knives, sticks, or bottle bombs, they must not retaliate…”

When clashes occurred, people sought refuge in the Chitralada Garden, the site of the royal residence, seeking the King’s protection as a last resort. His Majesty ordered all Royal Guards to remove their bullets and personally received the people, allowing the royal medical unit to treat the injured. Subsequently, he advised Field Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn, the Prime Minister; Field Marshal Praphas Charusathien, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Interior; and Colonel Narong Kittikachorn, the Prime Minister’s son, to resign and leave the country. At the same time, he appointed Thanin Kraivichien as the new Prime Minister. The riots and unrest came to an immediate end.

Subsequently, the Prime Minister signed the royal command appointing distinguished individuals from various professions—including civil servants, academics, merchants, village headmen, farmers, and even motorized tricycle drivers—a total of 2,347 people, as members of the National Assembly. Their task was to elect among themselves 299 members of the National Legislative Assembly. This Legislative Assembly quickly drafted a new constitution, which was promulgated in 1974, conducted elections for members of the House of Representatives, and established a government under the democratic system.

History has since recorded the King’s wisdom and royal authority, demonstrating that without the monarch, it is impossible to predict whether Thailand would have survived to the present day. It is also evident that after resolving the national crisis, His Majesty returned to his constitutional role, remaining above politics and politically neutral, leaving the administration of the country to the government. (Royal Grace in the Granting of Justice and Pardon, 1996: 25–63)

2.Royal Social Welfare

It refers to the king’s social welfare, the principle by which the monarch provides for the people, consisting of four aspects:

-

Sassametha: the wisdom in cultivating crops and promoting agriculture.

-

Purismetha: the wisdom in supporting civil servants and encouraging capable and virtuous individuals.

-

Sammapasa: the ability to unite the people by promoting livelihoods, such as providing loans to the poor to help them establish themselves.

-

Vajapeyya is the skill of gracious and persuasive speech—speaking politely, gently, and reasonably to foster harmony, understanding, and trust.

3.The Ten Principles of Chakrawarti Conduct are:

Antosanasamu Plakayasamu: Upholding Dharma in governance and supporting the royal family, officials, and the army.

Khattiyesu: Supporting kings and administrative officials throughout the realm.

Anuyantesu: Providing for followers, including civil servants.

Brahmankhapatiesu: Supporting Brahmins and wealthy citizens, such as doctors, merchants, and farmers.

Nekamchanpatesu: Supporting villagers and rural populations across the kingdom.

Samanaprahmanesu: Supporting monks and ascetics who uphold moral conduct.

Mikapakkhisu: Protecting animals, including certain meat and birds, from harm by the people.

Adhammakapattikhepo: Preventing and correcting wrongdoing to maintain order and protect citizens.

Anuppatanam Dhanupatanam: Distributing wealth to the poor to prevent destitution.

Samanaprahmanam Upasangkamitva Panhapajjhanam: Consulting virtuous monks and Brahmins to guide right action for the people.

Adhammarakassapahanam: Preventing misconduct, including improper sexual behavior.

Visamolopasala Pahanam: Abstaining from greed for personal benefit.

4.Conduct in accordance with Buddhist principles (Ekakasat Acharaya, 1996: 429–433)

In addition to faithfully practicing the Ten Royal Virtues, Chakrawartic conduct, and royal social welfare in an exemplary manner, His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej (Rama IX) also embodied other Buddhist principles that citizens should regard as models, as illustrated in the following aspects.

He exemplified supreme gratitude and filial piety.

In Buddhism, the principle of gratitude and filial respect is highly valued in Thai society as a hallmark of a virtuous person. This virtue has been passed down through generations, particularly gratitude toward benefactors, which encompasses four groups: (1) parents, (2) teachers and mentors, (3) the monarch, and (4) the Buddha, as well as all those who have provided care or support. Children, students, citizens, and Buddhists are expected to demonstrate respect and gratitude toward these figures. Society honors those who uphold this virtue as good and rare individuals, believing that such people will prosper.

His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej demonstrated to the world that he was “a monarch of extraordinary gratitude and filial piety,” particularly in his conduct toward Her Majesty the Queen Mother. During the illness and eventual passing of Her Majesty Queen Sri Nagarindra, His Majesty faithfully observed and attended to her with deep respect. Even while experiencing his own ailments, he endured personal suffering to visit and care for the Queen Mother regularly. As noted by Phra Thamadilok (Chan Kusalo) of Wat Pa Dara Pirom, Chiang Mai:

“…His Majesty exhibited unparalleled gratitude and filial devotion toward the Queen Mother. Throughout her illness, he consistently monitored her condition with respect. Despite his own health challenges during this period, he bore his suffering silently and visited her regularly…”

After the passing of the Queen Mother, His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej (Rama IX) continued to perform royal merit-making without interruption until the cremation was completed. He carried out all royal rites toward the Queen Mother perfectly according to tradition, including the royal crematorium and religious ceremonies. (Interview, 30 April 1996, Wat Pa Dara Pirom)

On the same matter, Phra Phisandhammapathi (Phayom Kliano) stated: “…Regarding the Queen Mother, His Majesty demonstrated the highest gratitude and filial piety. He visited her daily, holding her hand for an hour each day, departing from the palace at 3 a.m.—something no ordinary dutiful child could do. Moreover, after her passing, he faithfully fulfilled Buddhist duties, inviting monks to deliver daily sermons at the royal cremation site, two to three recitations per day, and he attended every day…” (Interview, 28 April 1996, Wat Suan Kaew)

The King’s exemplary conduct in gratitude and filial piety serves as a model for all citizens to follow. Those who already practice this virtue are encouraged to deepen their practice, while those who have neglected it are reminded to begin, helping to reduce the contemporary societal problem of abandoning parents and grandparents. This guidance addresses ingratitude and promotes a society that is compassionate, generous, and mutually supportive, where appreciation and respect are widely expressed beyond mere obligation.

He also embodied the Brahmavihara virtues.

In Buddhism, Brahmavihara refers to qualities that guide adults, such as parents, teachers, mentors, and the monarch. This virtue is emphasized in Thai society as a model for citizens to follow and express appropriately. As noted by Phra Thamadilok of Wat Pa Dara Pirom, Chiang Mai: “…Those in positions of responsibility, such as parents, teachers, mentors, or government leaders, should cultivate four qualities: loving-kindness (metta), compassion (karuna), sympathetic joy (mudita), and equanimity (upekkha), collectively known as the ‘Brahmavihara virtues.’”

Loving-kindness (Metta): This is the feeling of goodwill toward all people, regardless of nationality or social status. His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej (Rama IX) met with citizens at all levels and visited even the most remote areas. Moreover, while he was a devoted Buddhist, he extended his compassion to followers of all religions, honoring monks and religious leaders from Vietnamese, Chinese, Hindu, and other faiths, treating all religions with respect and fairness. This exemplifies his boundless loving-kindness.

Compassion (Karuna): His Majesty addressed a wide range of societal problems through royal initiatives. For example, the Royal Project helped hill tribe communities transition from illegal occupations, such as opium cultivation, to sustainable alternatives. Instead of simply forbidding such activities, he provided new crops—temperate flowers, fruits, and vegetables—for cultivation. Today, these crops form the basis of the Royal Projects, demonstrating his benevolence in relieving the suffering of the people and his wisdom in problem-solving.

Sympathetic joy (Mudita): The King honored and praised people at all levels, without showing personal displeasure or favoritism. He conferred royal decorations, recognized monks with ecclesiastical titles, and celebrated the achievements of virtuous individuals. This practice of rejoicing in others’ goodness exemplifies Mudita.

Equanimity (Upekkha): His Majesty remained impartial, showing no bias toward any group or individual, and did not punish or favor anyone unfairly. He maintained a balanced mind, treating all equally. Furthermore, he regularly imparted the importance of the Brahmavihara virtues to those around him, such as in his royal address to graduates at the College of Education, Phitsanulok, on 30 November 1972.

“At present, it is widely felt that youth-related problems in the nation are increasing due to various factors. In truth, young people do not intend to be troublesome. However, because they have not received sufficient care and attention, lack proper guidance, and lack those who can provide them with correct and appropriate advice, they become individuals who pose challenges to society.

It is therefore the duty of teachers, lecturers, and educational administrators to assist them with knowledge and ability. Everyone has studied guidance as a subject and should apply it in practice so that the youth may receive genuine benefit, particularly in terms of guidance for conduct and mental development, which are of great importance. Efforts should be made to instill sound knowledge and wholesome thinking equally among them, offering advice and training with reason, sincerity, and compassion, extending help and support to lead them toward the right and prosperous path. In this way, youth will gain confidence and encouragement to do good deeds, ensuring a stable and bright future.”

This demonstrates that His Majesty attached great importance to this virtue. Mom Rajawongse Akin Rapeepat, a devout Buddhist who had worked in several royal initiatives of His Majesty King Rama IX, remarked that “Our King is one of those rare persons, a true benefactor, who shows compassion and understands the suffering and happiness of others, helping them to overcome their hardships and attain happiness, even if it is like gilding the back of a Buddha image where no one can see.” (Interview, 9 May 1996, at the Crown Property Bureau) The royal conduct exemplifying the Brahmavihara virtues stands as a sheltering shade, protecting and nurturing Buddhists and people of all faiths, bringing peace and stability to society, and serving as a noble example for Buddhists to follow.

He was endowed with supreme diligence and perseverance. Perseverance, or tireless effort, is a virtue that Thai society and Buddhists seek to cultivate in their sons and daughters, with the belief that whoever possesses this principle will attain success and fulfillment in life, along with happiness, prosperity, and stability. Moreover, it contributes to the advancement of society and the nation as a whole.

King Rama IX was endowed with great perseverance and diligence. On this matter, Phra Dhammakosajarn (Panyananda Bhikkhu) remarked, “…This King has most admirable royal conduct. Apart from His Majesty’s kindness and compassion, He also possessed unparalleled perseverance and effort. He constantly traveled to visit the people across the country—north, south, east, and west—to care for their well-being. Wherever there was suffering, His Majesty went to help. In times of drought, He personally sought ways to assist. He did everything for the benefit and happiness of the people, in accordance with His royal pledge that “We shall reign with righteousness for the benefit and happiness of the Siamese people.” He exerted himself tirelessly to fulfill the goals He had set. His life was a life of giving; wherever He went, He went to give—offering happiness to all His subjects. He worked ceaselessly, never resting. While officials take annual leave, His Majesty never took leave; He worked day and night without pause. Even when residing in the palace, He continued His duties. He was truly a King devoted to His people twenty-four hours a day. While officials often work less than eight hours, arrive late, or leave early, His Majesty had no limits to His working hours. He carried out His royal duties solely for the welfare of the people—whether highlanders or lowlanders, in the north, south, central, or eastern regions—everyone received His boundless benevolence. This was evident and deeply felt in the hearts of all Thai people.”

The Thai people know His Majesty as a King of great compassion toward His subjects. Living under His benevolent grace, we should follow His example, for He worked so tirelessly that perspiration streamed down His nose.” (Interview, May 2, 1996, at Wat Chonprathan Rangsarit). On the same matter, Phra Phisan Thammaphathi (Phra Phayom Kallayano) remarked, “The image of His Majesty’s perspiration flowing down His nose is a reflection of His tireless devotion to His royal duties for the people. In plain words, it shows that He worked until sweat poured down His face. This image serves as an inspiration for Buddhists to dedicate themselves with sacrifice and perseverance, working diligently for the benefit of Buddhism and society.” (Interview, April 28, 1996, at Wat Suan Kaew).

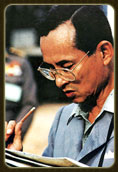

Professor Rapee Sakarik, former President of Kasetsart University, recalled that on one occasion he had the opportunity to accompany His Majesty the King to survey the area of Doi Ang Khang for the purpose of initiating a development project. His Majesty traveled along the ridges and slopes, covering the rugged natural terrain of about 8–9 kilometers. Despite the exhaustion that caused perspiration to stream down His body, He never faltered. His Majesty took lunch from a simple packed meal on a bamboo platform and remained determined to fulfill His royal intention. While proceeding on the route, He held a map and a camera in His hands, continuously collecting data and analyzing the area. The results of this survey later became the Royal Project for the development of Doi Ang Khang.

Meanwhile, Professor Rawee Pawilai, Director of the Chulalongkorn University Dhamma Center, stated that after the nightly chanting of funeral rites for the King’s mother, His Majesty would summon those responsible for solving the flood problems in Bangkok and surrounding areas. He provided guidance, direction, and explanations using maps and physical diagrams, ensuring that all parties involved clearly understood and were able to carry out the work. These efforts alleviated the suffering of the people and eventually led to the establishment of both short-term and long-term flood prevention projects. Despite having many royal duties during that period, His Majesty continued to devote Himself tirelessly. This demonstrated not only His boundless compassion but also His remarkable perseverance, serving as an example and inspiration for all to dedicate themselves selflessly for the greater good.

Mr. Phawat Bunnag, former Deputy Private Secretary to the King, summarized five customary royal conducts as follows: In addition to embodying the Ten Royal Virtues, His Majesty the King also upheld the role of the five heirs (Benjathayat), namely:

The Royal Heir: preserving sovereignty and succession in accordance with the Palace Law of Succession.

The Family Heir: serving as the elder of the royal lineage, in accordance with the wishes of past monarchs.

The Religious Heir: serving as the Supreme Patron of Religion, as prescribed by the Constitution.

The Dharma Heir: genuinely devoted to and steadfast in the teachings of the Buddha.

The Beloved Heir: revered and beloved by the people, akin to King Chulalongkorn the Great, to the extent that the people bestowed upon Him the title King Bhumibol Adulyadej the Great. (Kawee Isariwan, 1993)

5.His Majesty’s Royal Determination and Ideals in Transforming Thailand into a Golden Land

“The creation of Thailand as a golden land, or the pursuit of self-reliance in the present, is seen as requiring the urgent establishment of peace. Without peace, it is impossible to contemplate solutions to problems or to unite in collective efforts for self-help. Peace outwardly means a normal state of affairs free from turmoil, conflict, exploitation, oppression, or malice. Inwardly, it means a mind undisturbed, free from restlessness and anxiety caused by greed, selfishness, harsh judgment, delusion, and arrogance—the root causes of all unwholesome and wrongful actions. The making of peace must therefore begin within oneself, in one’s own heart and mind.”

The royal aspirations of His Majesty the King and the ideology of a righteous and prosperous land were discussed by Professor Dr. Kamon Thongthamnat on August 9, 1986, at the Ambassador Hotel during the General Assembly of the Council of Social Welfare of Thailand (1987: 1-7). He defined the term “ideology” as follows:

“Every ideology refers to a system of thought and belief concerning goals and the proper means to lead a good life. It cannot exist or spread without the active participation of people who have faith in it, promoting, instilling, and putting it into practice. Ideology consists of two components: the ultimate goal and the approach to achieve that noble goal. Ideologies do not arise spontaneously; they are created by those who design and guide them.”

“Regarding social ideology, especially the ideology of nation-building and creating a stable and harmonious communal life, the person capable of establishing shared belief in both the national goal and the proper conduct to achieve it is the leader of society. In a small community, this leader is called a father; in a large society, it is the monarch or emperor.”

The monarch thus occupies a position above all other rulers in determining the ideology of the nation and the guiding principles for the lives of its people. This has been the case continuously from the Sukhothai period to the present. Therefore, the royal aspirations of the monarch constitute the ideology of the nation, and if the people follow and practice them, it will bring positive outcomes for the country.

For the ideology of the Thai nation during the Rattanakosin period, it is clearly reflected in the royal writings, royal aspirations expressed in essays, or royal speeches of the nine monarchs. In the reign of King Rama IX, His Majesty’s royal aspiration is stated in the first royal command: “We will reign over the land with righteousness, for the benefit and happiness of the Siamese people.”

The first part of this royal statement, “We will reign over the land with righteousness,” refers to the land of Dharma, meaning to make the land a land of righteousness. The second part, “for the benefit and happiness of the Siamese people,” refers to the land of prosperity, or the golden land. Therefore, the land of Dharma and the golden land signify a realm where the people live righteously and coexist harmoniously. This does not merely mean material prosperity; the golden land is a land where the people can live together in well-being, which is achieved when everyone upholds Dharma. At present, we have the guiding light, which is the current monarch, who has faithfully practiced the Ten Royal Virtues, the four principles of royal social responsibility, and the twelve practices of imperial governance. Through all these virtues, He is revered and loved by all Thai people and serves as the unifying center of the nation, embodying national unity.