King Taksin the Great

Chapter 14: Royal Activities in Transportation and Relations with Western Nations

14.1 For what purposes were roads constructed and canals excavated during the Thonburi period as part of royal activities in transportation?

King Taksin abolished the old belief that having many roads and transport routes would provide advantages to enemies and insurgents, and instead regarded it as more beneficial for commerce. Therefore, during the winter season, when the kingdom was free from warfare, he would order the construction and maintenance of roads to facilitate land travel, trade, and transportation, and the excavation of canals to serve as routes for merchants and the general populace, providing convenience for trade, the transport of goods, communication, and also strategic advantages (Praphat Trinarong, 1999: 20). Evidence of this appears in the records of the French missionary group who resided in Thonburi at that time (Collection of Chronicles, Part 39), which state as follows.

“ …During the winter season, King Taksin ordered the building of roads, which was contrary to the royal customs of earlier kings, and also ordered several forts to be constructed… ”

The major transportation routes in Thailand more than two hundred years ago were entirely waterways. One would scarcely hear of the construction of roads, except for Phra Ruang Road in the Sukhothai period. It may be said that the King of Thonburi possessed a remarkably modern outlook in national development.

14.1.1 The excavation of the city moat canals on the western and eastern sides

When King Taksin the Great established Thonburi as the capital, its territory extended to the Bangkok (Phra Nakhon) side. Thonburi originally had no city walls, so tamarind-wood stockades were erected along the canal encircling the city on both sides of the river. In 1772 he ordered the excavation of canals as recorded in the Royal Chronicles as follows.

“ …And he ordered the excavation of a canal to serve as the rear moat of the city, from Khlong Bangkok Noi to Khlong Bangkok Yai (according to the astrologers’ record, excavated in the year 1135 of the Chula Sakarat era, corresponding to 1772, understood to refer to what is now called Khlong Ban Khmin in one section, Khlong Ban Mo in another, and Khlong Wat Thai Talat (Wat Molilokkayaram) leading out to Khlong Bangkok Yai). The excavated earth was heaped up to form ramparts on the inner side along three directions, except the riverfront, and the eastern bank was similarly surrounded with stockades. A canal was excavated as a rear moat from the old wall behind Fort Vichaiyen, curving upward to the sacred shrine at the headland, reaching the river on both sides, north at Tha Chang of the Front Palace and south at the mouth of Khlong Talat. The excavated earth was heaped into ramparts on three sides, and bricks from the Pho Sam Ton stockade and the Sikhuk stockade, and from Bang Sai and Phra Pradaeng, were brought to build the walls and forts along the ramparts on three sides (N. Na Paknam, 1993: 53), except for the riverfront, which was left as it was, with the river running in the middle like the city of Phitsanulok (the split-city). ”อ

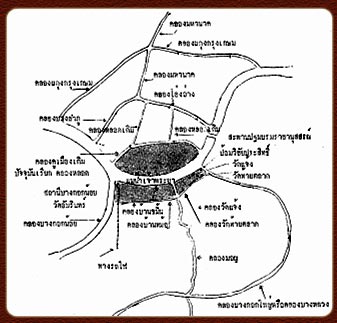

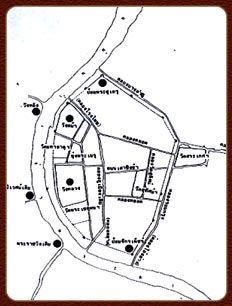

Map showing the territory of Thonburi when it was the capital

Thonburi, western side, bordered Khlong Ban Khmin, Khlong Ban Mo, and Khlong Wat Thai Talat

Thonburi, eastern side, bordered the city moat canal, now called Khlong Luad

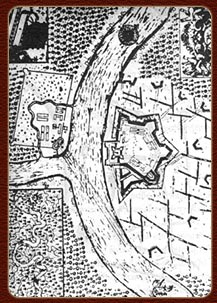

The area of the fort on both sides of the Chao Phraya River, at the mouth of Khlong Bangkok Yai, in Bangkok during the Ayutthaya period

(Image from the book Thonburi Palaces and Communities of the Siamese)

Note: The area now called “Khlong Ban Khmin” is on the Thonburi side, but it was originally the remains of the western city moat canal that still existed in the past. It was a Thonburi city moat connecting Khlong Bangkok Noi with Khlong Bangkok Yai. Today, Arun Amarin Road runs along the former canal, and shophouses built along it have encroached on the area, causing it to become neglected and polluted, losing its function as a city moat for defense against enemies.

Fort Vichaiyen was located at the rear of the palace. Later, King Taksin ordered it to be renamed Fort Vichai Prasit (Interesting Facts about Thonburi, 2000: 88).

The eastern city moat canal of Thonburi, on the Phra Nakhon side, was excavated during King Taksin’s reign, connecting the Chao Phraya River from Pin Klao Bridge to the mouth of Khlong Talat. It was commonly known as Khlong Luad. Remains of brick foundations from the city wall can still be found along the canal, shaded by trees, providing a pleasant and refreshing environment. However, parts of the eastern city moat were later covered by roads and bridges (Suchit Wongthet, 2002: 60).

This eastern city moat was later named “Original City Moat Canal” on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of Rattanakosin in 1982 (Sansanee Weerasilpchai, 1995: 38-39).

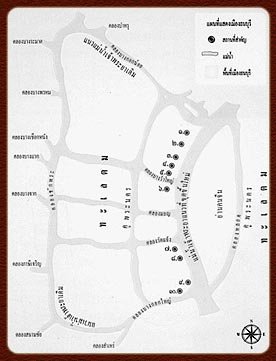

Map showing the city of Thonburi

1. Wat Amarintharam

2. Rear Palace

3. Mangkhut Garden Palace

4. Ban Poon Palace

5. Wat Rakhangkhositaram

6. Royal Residence

7. Wat Arun Ratchawararam

8. Former Palace

9. Fort Vichai Prasit

10. Wat Molilokkayaram

(Image from the book Interesting Facts about Thonburi, 2000: 87)

When King Phutthayotfa Chulalok the Great established Bangkok as the capital, he ordered the excavation of a new city moat parallel to the original city moat on the Bangkok side to expand the capital’s territory. The original city moat therefore ceased to serve as a defensive moat and became a transportation route for the city’s residents. The populace referred to the canal in sections according to the important locations it passed. For example, the northern mouth passing the Royal Silk Factory was called “Khlong Rong Mai,” the southern mouth at the bustling land and water market was called “Pak Khlong Talat,” and the middle section between the canal beside Wat Buran Sirimatthayaram and the canal beside Wat Ratchabophit Sathit Mahasimaram Ratchaworawihan was designated “Khlong Luad” by a Sanitation Department announcement in R.S. 127. This likely meant a canal connecting two larger parallel canals at intervals, linking the two city moats. However, in later times, the general public commonly referred to the entire canal as “Khlong Luad,” which is inaccurate.

In summary

“ …On the western side of Thonburi, he ordered the excavation of a canal connecting Khlong Bangkok Noi and Khlong Bangkok Yai, the remains of which can still be seen today and are called Khlong Wat Wiset, running parallel to present-day Arun Amarin Road. On the eastern side (on the Phra Nakhon bank), he ordered the excavation of a city moat from the area of the present Pak Khlong Talat Fort to the Chao Phraya River at the location of the present Phra Pin Klao Bridge in front of the National Theatre, commonly known today as ‘Khlong Luad.’ Therefore, the ‘Khlong Luad’ in front of the Ministry of Interior is the eastern Thonburi city moat, and ‘Khlong Wat Wiset’ is the western Thonburi city moat. Importantly, with the Chao Phraya River running through the middle of the city, Thonburi came to be known as the ‘Split-City’ (Suchit Wongthet, 2002: 26).”

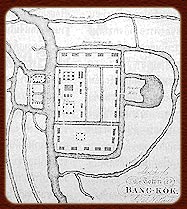

Map of Bangkok, printed by Henry Colburn, London, June 1828

(Image from Silpa Wattanatham Journal)

The atmosphere of Khlong Luad in the past, used for travel and trade

Currently, it is used as a drainage canal (Image from the Drainage Department)

Note

During the reign of King Phutthayotfa Chulalok the Great, he graciously ordered the excavation of additional canals in 1783 (B.E. 2326), connecting the original city moat canals with the outer city canals for strategic and transportation purposes. There were two canals, but no official names were given; they were generally called “Khlong Luad” according to their characteristics.

Khlong Luad Wat Ratchanadda began from the original city moat, between the Royal Hotel (Rattanakosin Hotel) and Wat Buran Sirimatthayaram, passing Thanon Tanao, Wat Mahannaram, Thanon Ban Dinso, the Bangkok City Hall, Wat Ratchanadda, and Thanon Maha Chai, until it joined the outer city canal at Wat Ratchanadda. This canal was originally called Khlong Luad without a specific name, but later sections were named according to the locations it passed, such as Khlong Buran Sirirat, Khlong Wat Mahann, Khlong Wat Ratchanadda, and Khlong Wat Thepthida.

Map of Bangkok during the reign of King Phutthayotfa Chulalok the Great

(Image from Modern Thai History)

Khlong Luad Wat Ratchabophit began from the original city moat at Wat Ratchabophit, passing Thanon Ratchabophit, Thanon Ban Dinso, and Thanon Maha Chai, until it joined the outer city canal at the north of Damrong Sathit Bridge. This canal was also known as “Khlong Saphan Than,” but officially referred to as “Khlong Wat Ratchabophit.”

On the occasion of the 200th anniversary of Rattanakosin, the government of His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej, the present monarch, by Cabinet resolution on 13 June 1967, officially designated the names of these two canals to preserve them as historical monuments: “Khlong Luad Wat Ratchanaddaram and Khlong Luad Wat Ratchabophit” (Canal System Division, Drainage Department, 2003, http://dds.bma.go.th/Csd/canal_1.htm, 8 July 2004).

14.1.2 In addition, he also ordered the excavation of a canal in Nakhon Si Thammarat, as stated in the following text:

“Regarding canal excavation, evidence appears in the copy of the decree establishing King Khattiya Ratchanikom Sommot Mai Sawang, King of Nakhon Si Thammarat, in 1776 (B.E. 2319), stating that he ordered the urgent excavation of Khlong Tha Kham to reach the outer sea, or the western sea, which is now known as the Indian Ocean, to facilitate maritime trade routes and the supply of naval forces to the outer sea.”

The decree further states:

“ …Firstly, Khlong Tha Kham, which leads to the western sea, had previously been ordered for excavation but was not yet completed; observe the progress carefully in mind, so that the order for completion can be issued later… ” This indicates that the development of transportation in Thailand during the Thonburi period included both road construction and canal excavation. In the Rattanakosin period, road construction began in the reign of King Rama IV (Sethuon Supasopon, 1984: 52).

14.2 Royal Activities in Relations with Western Countries

During the reign of King Taksin, Thailand maintained diplomatic and trade relations with several Western countries, including Portugal, the Netherlands, England, and France, though contacts were primarily commercial. Eastern countries that traded with Thonburi included China, Java (then referred to as “Khaek Mueang Yakka Tra,” now Indonesia), and the Malay states (Malaysia), among others, which brought revenue to Thailand through port fees and import-export taxes under the Thai taxation system of that period.

Some historians have praised the Thonburi period as an era of flourishing trade for both the populace and the royal government. The most significant commerce was maritime trade, with goods loaded onto junks for export to various countries in the region. Once the country gradually returned to stability, King Taksin focused on promoting maritime trade extensively, as it was the most effective method to generate substantial revenue for national expenditure. Records indicate that during the Thonburi period, Thailand dispatched royal junks on multiple trade routes, eastward to China and westward to India. At times, as many as eleven royal junks were sent out simultaneously, which was a considerable number for that era. The profits from maritime trade significantly alleviated the burden of taxation on the populace.

Maritime trade was considered a crucial activity in the reconstruction of the Thai nation. Beyond the profits, which were the primary goal, it cultivated a love of commerce among Thais, enabling them to become skilled traders expanding their trade far and wide. It also prevented trade from falling entirely into foreign hands and safeguarded the benefits of local products from being neglected. This period marked a relatively prosperous phase in commercial development (Sanan Silakorn, 1988: 37).

French junk Indian junk

(Image from the book Boats: Boats: Culture of the Chao Phraya River Basin)

Japanese junk

(Image from Silpa Wattanatham Journal)

14.2.1 Trade Relations with Portugal

During the Thonburi period, there was some commercial contact with the Portuguese. In 1790 (B.E. 2333), the Portuguese and Moors from Surat (a city in India), which was then a Portuguese colony, came to trade with Thailand. Thailand also dispatched royal junks to trade with India, reaching as far as Goa and Surat, but no formal royal diplomatic relations had yet been established between the two countries (53 Thai Kings Who Won the Hearts of the Thai People, 2000: 246).

Portuguese junk

(Image from the book Boats: Culture of the Chao Phraya River Basin)

English junk

(Image from the book Boats: Culture of the Chao Phraya River Basin)

14.2.2 Trade Relations with England

During the reign of King Taksin, he sought to acquire modern weapons and military equipment for use in warfare.

The country from which Thailand most importantly procured weapons was England, which had its center in India and was expanding its power into the Malay Peninsula (present-day Malaysia and Singapore). England sought to establish a port on the Malay Peninsula to compete with the Dutch in trade, serving as a harbor for both warships and merchant ships. A key figure in this effort was Francis Light (Francis Light Sq.), known in older Thai documents as “Kapitan Lek” or “Captain Lek,” a former officer of the British Royal Navy.

Francis Light( Captain Francis Light)

(Image from http://www.thum.org/albums/penang03/ 0006_Statue_of_Sir_Francis_Light.jpg )

Captain Light resigned from government service to become an important ship captain for the British East India Company, a highly influential trading corporation of England at that time. He frequently sailed for trade in this region and associated closely with Malay people, becoming widely known. He later came to reside for a long period in Thalang (Phuket), where he took a Thai-Portuguese wife native to Thalang. He also became well acquainted with the Governor of Thalang and with Lady Chan, or Thao Thepkasattri, the heroine of Thalang. In short, Francis Light was, at that time, an Englishman widely known and respected both in commercial circles and among the local nobility throughout the region. Therefore, King Taksin appointed Captain Francis Light to be responsible for procuring weapons for the Siamese government. A royal letter was sent in 1777, and Francis Light duly carried out the task as requested.

This appears in a letter that Francis Light wrote to George Stratton, dated 23 June 1777, regarding King Taksin’s intention to purchase firearms: “…The King of Siam has heard that the Burmese are taking great interest in the French. The Burmese alone, he does not fear, but he is concerned that they may combine with the French, who are numerous in Pegu and Ava. He foresees danger approaching the kingdom. Even though he obtained 6,000 guns from the Dutch at Batavia at the price of 12 baht each, and is to receive another 1,000 this year, he nevertheless does not wish to depend much on the Dutch. Therefore, the King of Siam has requested me to procure a large quantity of small firearms for him, as many as can be obtained. I have promised that I will exert all efforts to acquire them according to his wishes. The King of Siam informed me that his forces will attack Mergui this season…”

The Royal Chronicles of King Rama I mention that in 1776 Captain Light sent 1,400 flintlock guns as tribute to King Taksin, together with various gifts:

“In the tenth month, Captain Lek, the English ruler of Koh Mak, sent 1,400 flintlock guns together with various tribute items.”

There is also evidence that the Chief Minister of the Treasury during the Thonburi period once wrote to a Dane who served as the governor of Tranquebar, a trading port in southern India, requesting that he assist “Kapitan Lek,” who had been assigned to purchase 10,000 flintlock guns there. In recognition of his service and his help in procuring firearms for the defense of the kingdom, King Taksin granted Francis Light the noble title Phraya Ratcha Kapitan around the year 1778.

During the reign of King Taksin, Siam (Thailand) maintained excellent relations with England. It is recorded that the King instructed Chao Phraya Phra Klang to send a letter to the British authorities in Madras, India. George Stratton, the acting governor of Madras at that time, sent a letter to King Taksin dated 18 July 1777 (B.E. 2320), along with a gold sword adorned with jewels as a gift. At the end of the letter, he requested that King Taksin kindly allow Francis Light to conduct trade in Siam without difficulty. Thus, during the Thonburi period, Siam enjoyed good relations with England. Later, Francis Light made great efforts to bring Penang Island (Koh Mak) under the control of the British East India Company, to which he belonged. His aim was to use the island as a harbor for warships and merchant ships on the western seas (Indian Ocean) and as a trading post to compete with the Dutch, who had established a stronghold in Malacca. Light used all his skills and efforts to negotiate the lease of Penang Island from Phraya Tairuburi, the local ruler, as the city of Tairuburi was then a vassal state under Siam.

Dutch junk

(Image from the book Ships: Culture of the Chao Phraya River Basin)

Phraya Tairuburi, fearing that the Siamese army might attack Tairuburi (since at that time the Siamese forces were advancing to drive out the Burmese in the southern provinces during the Nine Armies War), agreed to allow the British to lease Penang Island in 1786 (B.E. 2329), the fifth year of the reign of King Phutthayotfa Chulalok.

Francis Light was then appointed as the first administrator of Penang Island (originally called Koh Mak) or the first governor of Penang. He renamed the island Prince of Wales Island in honor of the Prince of Wales of England.

14.2.3 Trade Relations with the Netherlands

In the year 1770 (B.E. 2313), merchants from Terengganu and Jakarta (then called “Yakkatra” in Java, the capital of present-day Indonesia) presented 2,200 matchlock guns while King Taksin was preparing to lead a military campaign against the Phang Rebellion. This indicates that the Dutch were another European nation trading with Thailand during the Thonburi period, as at that time the Dutch had authority over Java.

Matchlock guns or stone-powder firearms

(Image from Thai Military History in the Reign of King Chulalongkorn)

14.2.4 Relations with France

When King Taksin the Great successfully established Thonburi as the capital, Father Corre, who had been the teacher of Gallash General and had escaped the Burmese roundup, came to pay respects along with about 400 surviving Catholics. They were granted land to build the Santa Cruz Church on 14 September 1769. Some Catholics were selected to serve in the royal administration and cooperated closely with the government until the end of their lives. In 1773, Father Joseph Louis Coude was sent from Paris to replace him. Toward the end of King Taksin’s reign, there were several disagreements that displeased the king, leading to his exile to Phuket until the end of the reign. It can be said that there is no evidence of trade with France, except for relations in the religious sphere (The Intelligent King, Office of the University, 1996: 509).