King Taksin the Great

Chapter 13: Royal Duties in Arts and Culture

13.1 How did people dress in the Thonburi period under King Taksin, including male common officials and women?

13.1.1 Royal Attire

“…The clothing in the Thonburi period continued the practices from the late Ayutthaya era, though some parts are evidenced as belonging directly to the Thonburi period. These may be classified as follows.

King Taksin

Hairstyle and headdress – He wore the Mahatthai hairstyle, for which there is evidence confirming that during the reign of King Prasat Thong Thai men already wore this style. Van Vliet wrote that from above the ears the hair on the head was carefully trimmed, becoming shorter near the neck, and lower down the hair was shaved.”

Somdet Chao Phraya Borom Maha Sri Suriwong (Chuang Bunnag), photographed by John Thomson in 1865, wore the Mahatthai hairstyle.

Mom Rachotai (M.R.W. Kratai Isarangkun), author of Nirat Lon, photographed by John Thomson in 1865, wore the Mahatthai hairstyle (from the book Thai Costume: Evolution from Past to Present, Volume 1).

It was the Mahatthai hairstyle, in which the hair around the head was shaved, leaving hair about four centimeters long at the crown, combed and arranged as deemed proper.

The Mahatthai hairstyle

(courtesy of Muang Boran)

Male nobles wore the Mahatthai hairstyle or the Lak Chao style. Thai men had worn these styles since ancient times, until the reign of King Rama V when Western haircuts began to replace them. The photograph from the archives is undated (from the book Picture Book of Thailand).

Side-parted royal headdress and upturned royal shoes

(courtesy of Muang Boran)

During military campaigns, he likely wore the side-parted royal headdress, as it was a headdress with minimal decoration, made of sturdy material suitable for practical use. The side-parted headdress was made of leather, shaped like a cut gourd, with a surrounding brim, lacquered black, covering the collar and ears. “It resembled Japanese armor” (Sanun Silakorn, 1988: 144).

Royal shoes

Normally, he wore upturned royal shoes, but during military campaigns they were made of leather. His attire varied according to different occasions, for example:

When traveling abroad to receive foreign envoys, he wore six primary regalia items: a ceremonial outer robe in Asawari stripes 1, an outer robe with borders in gold, silver, or green 1, primary headdress including the crown adorned with diamonds, rubies, and emeralds matching the robe 1, embroidered leg guards 1, jeweled sash 1, and a sword at the waist 1, totaling six items.

When attending a royal cremation at Wat Chaiwatthanaram, traveling by the King’s boat, he wore six items: a ceremonial outer robe in Thai style 1, an outer robe with silver-ground Thai pattern 1, primary headdress with crown matching the robe 1, embroidered leg guards 1, jeweled sash 1, and a sword at the waist 1, totaling six items.

When traveling to Phra Phutthabat, from the city up to Tha Chao Sanuk by the royal boat, he wore seven items: two-layered upturned leg guards 1, pleated sash 1, raised ceremonial outer robe 1, jeweled sash 1, five-pointed petal-style crown 1, sword at the waist 1, and he held a ceremonial light 1, totaling seven items.

When setting out the royal procession from Tha Chao Sanuk up to Phra Phutthabat, he wore four items: royal traveling attire 1, upturned leg guards 1, jeweled sash 1, and European-style crown with plume 1.

When traveling to Pak Pa Thung Ban Mai, he removed the traveling regalia, and the regalia were provided for the royal boat journey from the city. Upon reaching Than Kasem, he removed the regalia. In the afternoon, when proceeding to pay homage at Phra Phutthabat, he wore the following eight items if riding the golden Phutthala boat: two-layered upturned leg guards 1, pleated sash 1, jackfruit-thorned sash 1, ceremonial robe with small golden patterns 1, white outer robe 1, decorated sash 1, white crown with gold trim matching the robe 1, and sword at the waist 1, totaling eight items.

Upon reaching Phra Phutthabat and going on a forest excursion, he rode elephants in royal traveling attire and horses in foreign-style attire. Horses in traveling attire were allowed when visiting Wat Phra Si Sanphet and performing temple ceremonies, wearing a tall pointed crown with feathers 1, white patterned sash 1, Japanese-style ceremonial robe 1, palanquin with roof or empty palanquin allowed, two-layered leg guards decorated with gems and pearl chains, dragon embroidery adorned with gems 1, pleated sash in green, red, purple, and gold with gem embellishments, sash tassels in gold 1, raised circular ceremonial robe in ruby bronze with gold and pearl chains 1, Suwan Krom robe in green with gold leaf embellishments 1.

For the Maha Phichai royal carriage and the royal boat journey to present the Kathin robe, he wore: gold chest sash with red gems, six sandalwood flower plates 1, Maha Sangwan gem necklace with rubies and emeralds 1, skirt embellishments with various gems 1, decorative outer skirt with hanging gems 1, Maha Phichai crown 1, earrings with emeralds 1, rings 1, gold bracelets with enamel and gems 1, enameled royal shoes with gems 1, totaling thirteen items.

For war regalia for elephant combat, he wore: inner leg guards 1, indigo-dyed inner ceremonial robe 1, outer black silk leg guards 1, outer padded ceremonial robe 1, inner crown 1, outer side-parted headdress 1, black jeweled sash 1, totaling seven items.

For expeditions to capture animals in Lopburi, Sa Kaeo, Nam Jon, tiger enclosures, elephant hunts, and taming elephants in the fields, he wore traveling regalia, with pointed feathered crown… (from The Life of King Taksin the Great, Committee of the King Taksin the Great Foundation, 1980: 144-147; Thai Costume: Evolution from Past to Present, Volume 1, 2000: 202-204).

13.1.2 Attire of Officials: According to the records in the royal treatise on primary regalia, regarding the regulations on the duties and authority of officials, police, and royal pages, it is stated as follows.

- For officials attending full ceremonial royal events, the leaders of ten-thousand, attendants, and sergeants, as well as those covering silk or boarding the royal boat, wore patterned lower garments, draped ceremonial jackets, shoulder sashes, and waist sashes according to rank, with swords worn according to position.

- Ordinary royal pages wore patterned lower garments, draped ceremonial jackets, and sashes.

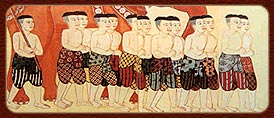

Color painting of the royal land procession in the Ayutthaya period, modeled from the mural of the ubosot at Wat Yom, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya Province (from the book The Life of King Taksin the Great).

Color painting simulating the attire of ordinary royal pages (from the book The Life of King Taksin the Great).

For the “Chao Thi” of the Chao Thi Department, responsible for maintaining order in buildings and premises, the attire for royal ceremonies was as follows: for senior members, they wore patterned lower garments, draped ceremonial jackets, sashes, and wore swords.

For the police, divided into four departments—Outer Police (left 1, right 1) and Inner Police (left 1, right 1)—the regulations stated:

“When attending royal entertainments, the chief of the department wore patterned lower garments, draped ceremonial jacket; the department chief carried a sword, the assistant carried a sword; leaders of ten-thousand carried swords and spears; colored sashes around the waist; secretaries wore silk lower garments, long sash, waist sash, and carried swords following the procession.”

For less important events:

“Patterned lower garments, ceremonial jacket, sash.”

For hazardous events, such as observing tigers in the palace:

“Silk lower garments, waist sash.”

For processions outside the palace during such events:

“Silk-striped lower garments, overcoat, waist sash.”

For regular events inside the palace or minor events outside:

Regular events: “Patterned silk lower garments, ceremonial jacket, sash.”

Full ceremonial events: “Patterned lower garments, draped ceremonial jacket, sashes according to rank.”

Full ceremonial processions: “Patterned lower garments, overcoat, jeweled sash; department chief carried a sword, assistant wore a sash and sword; leaders of ten-thousand carried spears and swords; colored sashes around the waist; secretaries carried swords.”

Notes:

1. The overcoat refers to the garment called the inner coat.

2. Hats in the reign of King Narai, following military styles, included garland-brimmed hats, leather hats, Western-style hats, traveling hats, and hairstyles such as the Mahatthai hairstyle.

3. Generally, uniforms for warrior-nobles were sewn from silk and muslin. The sanob jacket or annual ceremonial cloth granted by the king was worn only for royal ceremonies or when accompanying the king on travels; it was not worn for ordinary occasions. When worn out, the official was to respectfully request a replacement from the king.

King Taksin granted Chao Phraya Mahakasatsuek a dark sanob jacket, patterned silk with large Nāga motifs, six-breadth lotus-patterned white sash, six-breadth window-patterned sash, and upturned leg guards.

Rewards for nobles who distinguished themselves in war were granted according to the Mandetianbal regulations:

“Any commander or subordinate who goes to battle and defeats the enemy, raising the standard in accordance with the law, shall receive rewards of gold, sanob jacket, and other garments; these are to be maintained and passed on to descendants as a reward.”

“If anyone engages in elephant combat, the reward shall be a golden hat, golden sanob jacket with raised sleeve ends, up to 10,000 rai; they shall also receive a golden carrying pole and gold staff.”

Additionally, the Mandetianbal regulations describe other noble attire, such as for nobles with a fief of 10,000 rai: the headgear is a gold topknot hat; for seated city nobles, a gold topknot hat; nobles with 10,000 rai holding city authority wear a golden turban.

Noble attire

Ceremonial jackets were made of hemp fabric (presumed to be lightweight cloth), thin and light, with hems reaching mid-calf.

The Sena Kut jacket is a military uniform for both land and naval forces, dating back to the Ayutthaya period. It was made of patterned cotton fabric imported from India and sewn in the Chinese style, with buttons fastened along the right side. The front, back, and upper arms on both sides featured lion motifs holding armor. At present, only two pieces remain in the National Museum, Bangkok. This image is from the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, Canada (from the book Thai Costume: Evolution from Past to Present, Volume 1).

Outer jacket – made of silk from China or European fabrics, embroidered with gold thread in beautiful patterns, with a front opening fastened by buttons braided from silver or gold at intervals. The sleeves were wide. The fabric is presumed to be Indian or Persian brocade, such as Khemkhab, Atlat, or Yierbap.

Neck sash – made of Chinese silk, embroidered with silver or gold thread, or using the finest available fabric, possibly Indian or Persian brocade, such as Khemkhab, Atlat, or Yierbap, considered high-quality and valuable.

Leg guards – made of fine fabric, embroidered with gold and silver threads in patterns at the lower legs, extending well below the knees.

Lower garments – presumed from records that the wrap-around cloth worn over the leg guards followed the chong kraben style.

Shoes – wore slip-on shoes resembling Moorish sandals.

Lom Pok – a noble’s hat, also called Pok or Kiew, a garment accessory indicating rank. It was a pointed hat similar to a crown, with the brim trimmed in yellow or gold thread for decoration. Above the brim was a circular Kiew decorated with gold flowers and a pointed tip. Sharewes noted an interesting classification of noble ranks based on betel boxes and Lom Pok hats.

Okya – the highest-ranking noble. The brim of the Lom Pok hat was made of gold, and the pointed tip was decorated with a floral garland.

Okphra – second-rank noble. The brim of the Lom Pok was made of Chaiyapruek floral motifs.

Okluang – third-rank noble. The brim of the Lom Pok was only two inches wide and less finely crafted than that of an Okphra.

Okkhun – fourth-rank noble. The brim of the Lom Pok was made of gold or plain silver.

Okmuen – fifth-rank noble. The brim of the Lom Pok was made of gold or plain silver, similar to that of an Okkhun.

The “songpak” or “sompak” cloth was the most important lower garment for officials. The songpak was official cloth granted by the king, indicating rank and affiliation. It was worn when attending audiences or accompanying royal travels. Even when leaving home to enter the palace, another cloth was first worn, and the palace attendants carried the sompak cloth to be worn within the royal precincts. Mural evidence shows this practice near the inner walls of the palace hall.

The songpak or sompak was narrow silk, joined to create width using two pieces called a “ploa,” resulting in a width of approximately 160 cm, wider than ordinary lower garments by one-fourth. The length was also one-half longer than ordinary lower garments. For full ceremonial dress, sompak with various patterns was used; for normal audiences, silk sompak in different colors was worn. The most prestigious sompak was the “sompak puem,” woven with floral motifs; the simplest type was striped sompak.

The method of wearing the sompak differed from the chong kraben style because the fabric was longer and wider. When worn, the cloth was divided into short and long sides. The short side was made equal to a normal chong kraben, with the end tucked in first. The long side was folded to match the short side against the body. Any remaining upper fabric was tucked under the original tuck and pulled up to form a front flap called a “chak phok.” The edges to be rolled were uneven in thickness: the right side was a single fold, the left side double-folded. Both sides were layered, then rolled into a tube similar to a normal chong kraben, but somewhat thicker, passed between the legs, and secured at the waist like a normal chong kraben.

Wrapping the cloth – In Ayutthaya-period documents, the term “kiew” frequently appears in regulations related to officials’ attire. Somdet Chao Fa Krom Phraya Naritsaranuwat defined it as a cloth worn around the waist, while “kiew lai” referred specifically to a waist cloth with a pattern.

Wrapping the Yan Phat cloth

Wrapping the Krawat Cham cloth

Wrapping the face cloth

Wrapping the Kelay cloth

(from the book Thai Costume: Evolution from Past to Present, Volume 1)

There was a style of wearing cloth called the “kiew-kelay” style, which required two patterned pieces of fabric. Somdet Chao Fa Krom Phraya Naritsaranuwat defined it as follows:

“One piece was worn as a chong kraben over the leg guards, and the other piece was worn as a waist cloth. At the back, it was spread downward to cover the buttocks; at the front, it was gathered and tied in a knot. One side of the cloth was aligned with the knot, while the other side was spread downward like a trailing vine and then folded back up and tucked into the waist, resembling a pouch hanging at the front of the legs. It is understood that the piece worn as the lower garment was called the chong kraben, and the piece worn around the waist was called the kiew. It is believed that originally the lower garment and the kiew were different types of cloth—the chong kraben wide, the kiew narrow. Later, this distinction was less observed; when there was no separate waist cloth, the chong kraben itself was used as the kiew, creating the messy style sometimes called patterned chong kraben or patterned kiew, in this manner.”

The term “kiew” also applies when worn over a shirt with an additional cloth tied over it. If a belt is used, it is called “kiew pan neng” with silver or gold cords. If a decorated cord is used, it is called “kiew rad prakot.” If embroidered cloth called “jearabat” is used, it is called “kiew jearabat” (Thai Costume: Evolution from Past to Present, Volume 1, 2000: 208, 214-216).

Attire of Common Men

Attire of Ordinary Men

(from the book The Life of King Taksin the Great)

13.1.3 Attire of Common Men – They wore chong kraben, raised Khmer-style lower garments, loose-style garments, or sarongs with a waist cloth. Most men kept their hair short and therefore often wore hats when going to battle, presumably for protection against weapons.

- Attire of Women

- Female court officials

For the jackets of female court officials or women, silk was layered according to rank. The types of silk varied by pattern, such as Dara Khor Leaw silk, Jamruat silk, Khaorop silk, gold-patterned silk, and Dara Khor silk. One could determine a female official’s rank by the type of garment and silk, as follows:

The chief queen wore gold-patterned silk, a jacket, and gold foot coverings.

Royal consorts wore gold-patterned silk, a jacket, and gold foot coverings.

Royal princesses wore Dara Khor silk, a jacket, and velvet foot coverings.

Grandchildren of the king wore gold-patterned Phok jackets (without foot coverings).

Lesser grandchildren wore Dara Khor Leaw silk jackets.

Royal concubines wore silk of various colors.

Wives of high-ranking officials above ministers wore Khaorop silk.

Wives of ministerial officials wore a jacket and Jamruat silk.

Court ladies wore pleated skirts with a draped sash.

These garments were designated for royal ceremonies only; at other times, all women wore the same simple cloth.

Ladies in the reign of King Rama IV (approximately 1801–1868) wore chong kraben, fastened with a gold belt with a gem-encrusted buckle, and draped a pleated sash made of Chinese silk.

(from the book Thai Costume: Evolution from Past to Present, Volume 1; Album of Thailand)

2. Common women wore chong kraben, usually in black or dark green, draped a diagonal sash, and secured it with a clasp. Their accessories included bracelets, pendants, necklaces, rings, and belts. Hairstyles were generally cut short into winged styles, although some evidence shows that shoulder-length wings were still occasionally worn (The Life of King Taksin the Great, undated: 135–138; Siam Araya 1(4), October 1, 2002: 87–88 by Abhisit Lai Sattruklai; Foundation for the Preservation of Ancient Monuments in the Former Palace, 2000: 116–120).

Note: In late Ayutthaya, there were four common hairstyles for women:

a. Bun in the center of the head

b. Winged style

c. Hair raised with decorative pins

d. Shoulder-length hair

Women often combined the winged style and shoulder-length hair in a single hairstyle: the top of the head combed into wings, with the hair left to fall to the shoulders on both sides. Additionally, the winged style was sometimes incorporated into the bun hairstyle.

Tiaras

(from the book King Naresuan the Great)

It is also noted that the winged hairstyle may have been worn with a head ornament, such as a tiara or crown.

The shoulder-length winged hairstyle for women is believed to have originated in the royal court and gradually spread until the fall of Ayutthaya. At that time, hair was cut short, leaving only the wings, to facilitate combat and disguise as men, with little concern for beauty, as the more masculine the appearance, the safer it was. In later periods, the winged style consisted of hair cut short around the crown following the hairline, forming wings, while the remaining hair was shaved, leaving only the roots. The winged hairstyle alone is occasionally observed, for example, in depictions of the Vessantara procession, which is believed to have been painted in late Ayutthaya.

For children, it was common to wear hair in a topknot. When they grew older and the topknot was removed, the area where the hair had been tied remained as a circular mark around the other hair, called the “hairline.” This hairline marks where hair had been plucked or shaved, such as the frontal hairline and the topknot hairline. The frontal hairline helped define the face clearly, creating a smooth, rounded shape like the moon. The topknot hairline, remaining on the head, indicated youth. Women who wished to preserve their youthful appearance often plucked the hair along this line in a circular pattern around the crown, as reflected in expressions such as “applying oil to protect the hairline” and “smooth hairline decorated neatly.”

Royal women wore the winged hairstyle, a style that Thai women had traditionally worn. Unlike men, women shaped the hairline above the forehead for beauty and often left side locks by the ears, sometimes called “tat hair.” The winged hairstyle persisted until the reign of King Rama V, when long hair became fashionable according to royal preference, and later evolved into the “dok kratum” hairstyle (see Thai Costume in the Rattanakosin Era for reference).

(from the National Archives, photographer and year unknown; from the book Album of Thailand)

The term “winged hair” refers to a style of wearing hair in which small tufts were left around the head. The hair was combed to create a clear border, sometimes parted in the middle or brushed back as desired for appearance. It is called “winged hair” because the hairline forms a distinctly visible edge.

Siamese nobility during the reign of King Rama IV, from the book Siam by Karl Dohring, page 28, provide a good example showing the traditional winged hairstyle with tufts on both sides.

(from the book Album of Thailand)

“Jon hair” refers to the winged hairstyle with a tuft left by the ears, extending downward and tucked behind the ear, hence called “ear tuft” or “jon hair.” Those wearing ear tufts had to keep the rest of the hair short to match.

The beauty practices of women, as recorded in the natural and political historical accounts during the reign of King Narai, and the tattooing of the human body, as documented in the La Loubere memoirs.

The beauty practices for women here included dyeing the teeth black and growing the nails, as well as coloring the nails and fingers red. It also reflects the cultural preference for tattooing on men’s bodies.

Dyeing the teeth black: Nicolas Cheruel recorded the customs and beliefs of the Siamese in the Natural and Political History during the reign of King Narai the Great, noting the practice of blackening the teeth as follows.

“What Siamese women could not bear to see in us was that we had white teeth, for they believed that only spirits and demons had white teeth, and it was considered shameful for humans to have white teeth, just like certain animals. Therefore, when boys and girls reached the age of 10–15, they would begin to blacken and polish their teeth using the following method.

Once a person was chosen to undergo this ritual, they would be laid on their back on the ground and remain in that position for three days while the ceremony proceeded. First, the teeth were cleaned with lime juice and then rubbed with a certain solution until they turned red. Afterward, they were polished with charred coconut shell until black. However, the women undergoing the process became very weak due to the strength of the solution, to the point that if a tooth were pulled out, it would cause no pain. Sometimes, teeth would even fall out when tested with something hard to chew. During these three days, they consumed only lukewarm rice gruel, which was poured slowly down the throat without touching the teeth. Even a slight breeze could compromise the ritual’s outcome. Those enduring this procedure had to lie fully covered until the pain from the teeth subsided and the swollen gums or mouth returned to normal.”

The above account reflects a Western worldview, offering one observation among many hypotheses for why Siamese people had blackened teeth. It is noteworthy that Sherves described the procedure in detailed step-by-step fashion, providing a clear picture. This suggests that the author likely traveled to several places, framing his observations based on experiences elsewhere, which may limit the accuracy of his view of the Siamese. In reality, it does not have to be entirely correct.

For the Siamese themselves, historical evidence dating back to the Sukhothai period shows that both men and women chewed betel, which naturally reddened the lips and blackened the teeth. This is one plausible reason for the blackened teeth of late Ayutthaya Siamese.

Sherves recorded that the Siamese also dyeing the nails and fingers red and growing long nails, stating that “…The same solution used to color the teeth red was applied to the nails and little fingers. Only high-ranking individuals were allowed to have long nails and red-dyed little fingers, while laborers had to keep their nails short, marking a clear distinction between the elite and commoners…”

The process of dyeing the nails and fingers red is not clearly documented, nor are the materials used. It is assumed that natural plant-based dyes were employed, such as the orange pigment from the stems of the ixora flower, for example (Thai Dress: Evolution from Past to Present, Vol. 1, 2000: 220-221).

13.2 Royal Duties in the Arts: What was the artistic style during the Thonburi period?

Since the second fall of Ayutthaya, many Thai artisans were scattered, killed, or lost, and a significant number were taken captive by the Burmese. Therefore, by the Thonburi period, only a small number of skilled Thai craftsmen remained. King Taksin of Thonburi had to rely on newly trained and revived artisans for the construction of permanent structures and other artistic objects, both for religious purposes and royal administration. These tasks were carried out by his military and civilian officials, indicating that these officials also possessed craftsmanship knowledge. It is assumed that the king gathered artisans of all trades in Thonburi to train and teach the new generation. The craftsmen of this period passed on their skills and contributed significantly to early Rattanakosin art.

However, the artisans of the Thonburi period were newly trained, and time for craftsmanship was extremely limited due to continuous warfare. The creation of artistic works had to be done hastily to meet urgent needs. Moreover, King Taksin’s reign lasted only 15 years, making finely crafted works from the Thonburi period rare. Thonburi-era arts can be categorized into four types as follows:

13.2.1 Ships – During the Thonburi period, shipbuilding flourished, including warships, trading ships, and fleet vessels for royal service. In King Taksin’s reign, the name of a royal vessel recorded was…

- Barang Kaew Chakraphat (The Glass Throne Barge)

- Si Sawat Ching Chai (The Victory and Prosperity Barge)

- Butsak Phiman Throne Barge

- Phiman Mueang In Barge

- Samphao Thong Tai Rot Barge (Golden Stern Junk Barge)

- Si Samut Chai Barge

After King Taksin of Thonburi restored independence, he ordered the construction of new royal ceremonial barges as follows:

- The royal barges Suwannaphichai Nawa Tai Rot

- Si Saklat and

- Khomya Pip Thong Thuep were constructed (Office for National Identity Promotion, 1996: 112).

13.2.2 Painting During the Thonburi period, although the era was dominated by intense warfare almost continuously, there still existed finely crafted paintings left as significant legacies. Among the most important, and still preserved at the National Library of Illustrations, Tha Wasukri, Bangkok, is the “Tri-Pun Burān Illustrated Manuscript of the Thonburi Period,” commissioned in 1776 B.E. (A.D. 2319). The “Tri-Pun Illustrated Manuscript” is a pictorial book written according to Buddhist principles. Such books have been created since ancient times, and several versions are preserved as national cultural treasures, including the Ayutthaya-era Tri-Pun Illustrated Manuscript and the Thonburi-era version. Creating a “Tri-Pun Illustrated Manuscript” was a difficult task, as it required not only accurate textual content drawn from Buddhist scriptures but also skilled painters to illustrate the entire volume, depicting hells, heavens, and various realms correctly and beautifully.

In this type of book, the illustrations are central, forming the core of the entire work. Only a monarch or a person of high authority, who genuinely valued art and had a sincere devotion to Buddhism, could undertake the creation of such a manuscript.

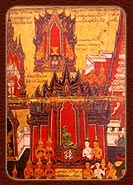

Depicts the Tavatimsa Heaven (Deva realm). Those who honor and respect their parents and the elders of their family, possessing generosity (not miserly) and great patience, are destined to be reborn in this realm.

(Image from the book King Taksin and the Role of the Chinese in Siam)

In the illustrated manuscript Traiphum Burana of the Thonburi period, the provenance is recorded as follows:

“In the Buddhist year 2319, 4 months and 26 days into the remaining intercalary period, on Tuesday, the 13th day of the waxing moon of the 11th month, Chula Sakarat 1138, the Year of the Monkey, King Taksin departed from the Thep Palace, Thonburi, with many royal attendants. Upon reviewing the stories in the Traiphum Burana manuscript, His Majesty wished that commoners and the fourfold clergy might understand the Three Realms and the Five Precepts, which are the origins of gods, humans, hells, asuras, pretas, and animals. He therefore commanded Chao Phraya Si Thammarat, the Grand Prime Minister, to prepare fine-quality manuscripts and deliver them to painters for illustrating the Traiphum. The work was to be done at the office of the Supreme Patriarch (Somdej Phra Sangharaja Si, the first Supreme Patriarch of Rattanakosin) at Wat Bang Wa Yai (present-day Wat Rakhang), who was to supervise and instruct the painters to depict the stories accurately according to the Pali texts and include Pali inscriptions wherever necessary, so that the teachings could be faithfully transmitted.” Thus, the Supreme Patriarch oversaw the process to ensure that both the illustrations and accompanying texts were accurate, orderly, and fully aligned with the canonical texts.

This manuscript can therefore be regarded as a true standard edition: exquisite in illustration, precise in content, and comprehensive in all aspects.

The four principal painters who executed this work with meticulous skill, fulfilling the royal commission, were:

1. Luang Phetchakam

2. Nai Nam

3. Nai Boonsa

4. Nai Ruang

Additionally, four scribes assisted in writing the explanatory captions:

1. Nai Boonchan

2. Nai Ched

3. Nai Son

4. Nai Thongkham

When creating the Traiphum manuscript, King Taksin of Thonburi gave special orders for the work to be carried out with meticulous care and strict supervision. In summary, His Majesty’s intention in commissioning this Traiphum Burana manuscript was to ensure that the general populace could correctly understand the realms of hell and heaven according to the Pali texts, and thereby be guided to diligently perform good deeds and refrain from evil, in accordance with the teachings of Buddhism for generations to come.

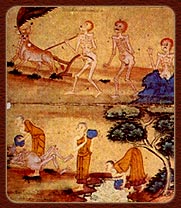

Depicted are two kinds of pretas:

1. Those who incurred sin for speaking carelessly to the Buddha Kassapa

2. Those who incurred sin for begrudging drinking water to humans and animals

(From the book “Somdet Phra Chao Taksin Maharaj and the Role of the Chinese in Siam”)

The pictorial Traiphum manuscript of the Thonburi period is regarded as one of the largest Traiphum pictorial manuscripts in Thailand. When fully unfolded, it extends to a length of 34.72 meters, with exquisitely executed color paintings applied on both sides of the folio pages.

The many dozens of illustrations contained in this Traiphum manuscript are remarkably beautiful and highly admirable, and it is difficult to find any other Traiphum pictorial manuscript that surpasses it in excellence.

Two manuscripts of this kind were commissioned during His Majesty’s reign. The other copy is now preserved in the National Museum in Berlin, West Germany, which acquired it from Thailand in 1893.

These two Traiphum pictorial manuscripts clearly demonstrate that His Majesty the King of Thonburi, in addition to restoring the nation and reclaiming its independence, also revived the arts and craftsmanship, and upheld the religion and moral conduct of the people in the nation (Sethuean Suphasopon, 1984: 6-7, 93-94).

Apart from the Traiphum pictorial manuscript, there are also mural paintings in the Phutthaisawan Throne Hall.

13.3.3 Fine Arts The Thonburi period possessed craftsmen skilled in this field, including lacquer artisans, decorative artisans, carvers, modelers, and painters. The important fine art objects of this era include the four gilt-lacquer Tripitaka cabinets in the Wachirayan Library of the National Library at Thawasukri in Bangkok, together with several other gilt-lacquer cabinets whose forms and craftsmanship closely resemble those of the aforementioned pieces, indicating that they were likely produced in the same period. These gilt-lacquer cabinets came from Wat Ratchaburana, Wat Chantararam, and Wat Rakhang Kositaram, showing that the craft of gold-on-lacquer decoration was another artistic tradition revived during the Thonburi period. In addition, there are mother-of-pearl inlaid Tripitaka cabinets in the mondop and in the Ho Phra Monthian Tham of Wat Phra Sri Rattana Satsadaram.

The royal Buddha image of His Majesty King Taksin the Great (with a simple robe)

(From the book “Analysis of the History of Buddhist Devotion and Buddha Images in Asia”)

In terms of casting, Luang Wichit Narumon was commissioned to model the Buddha images according to the Buddhist characteristics prescribed for examination, and a standing bronze Buddha and a meditating Buddha were cast, such as the principal Buddha image in the ubosot of Wat Mahathat.

Carving works include the royal bed platform and the platform for practicing Vipassana meditation.

1. The royal bed platform of His Majesty King of Thonburi, enshrined within the small vihara of Wat Intaram near Talat Phlu on the Thonburi side, is made of two wooden boards joined together, measuring 1.76 meters wide, 2.48 meters long, and 5 cm thick. It features a railing made of ivory, with carved ivory panels in elaborate phutthan flowers decorating the area beneath the railing. Posts for a canopy (mosquito net) are also fully assembled.

2. The platform for practicing Vipassana meditation, enshrined within the small ordination hall in front of the prang of Wat Arun Ratchawararam on the Thonburi side, near the former royal palace, is part of the original temple built since the Ayutthaya period, paired with the original prang (the current prang was constructed during the reign of King Rama III). This platform was made from a single wooden board, 7 feet wide and 20 feet long. Both platforms were crafted in a simple, plain manner without any particular beauty. Archaeologists consider the workmanship to be rather rough, indicating that it was produced by artisans whom His Majesty King of Thonburi had revived and trained, but who had not yet attained the skill level of master craftsmen.

The doors of the ordination hall porch and the doors of the top vihara porch of Wat Phra Sri Rattana Satsadaram

(From the book The Grand Palace)

In addition, there is a bench from Klaeng District, Rayong Province, which is preserved at the National Museum in Bangkok, as well as mother-of-pearl doors at the ubosot of Wat Phra Sri Rattana Satsadaram and the northern mondop.

13.3.4 Ceramics in the Thonburi Period (corresponding to 1768–1782)

When His Majesty King Taksin ascended the throne at Thonburi, trade with China began to expand. During this period, Siam continued to import porcelain from China for use, mostly five-colored Benjarong bowls with Thep Nop and Narasingh designs, with interiors coated in white glaze rather than the green glaze typical of the Ayutthaya period.

Benjarong Porcelain

During the Ayutthaya period, after the fall of the city for the second time in 1767, Chinese ceramics painted with overglaze using five colors—white, black, red, yellow, and green or blue—known as Benjarong, began to play a significant role in Siam.

Benjarong is a type of painted ceramic on glaze, commissioned by the Siamese court from China, specifically produced for Thailand. The designs painted on Benjarong followed Thai patterns, sent by the Siamese court to China for replication. Later, Benjarong became widely popular among Thai nobility.

Benjarong Porcelain

(From the book Somdet Phra Chao Taksin Chom Bodin Maharaj)

Benjarong porcelain is entirely covered with painted designs, leaving no empty space. During the Ayutthaya period, Thep Nop and Narasingh designs were popular, often accompanied by flame-patterned motifs, with interiors coated in green glaze. Later, the designs commonly featured royal lion, garuda, lion, Narasingh, kinnari, and hanuman figures, combined with flame-pattern motifs and scroll stems, among others. In addition, there were Benjarong ceramics painted with Thep Nop, floral, and leaf designs, which were designed and painted by Phra Ajarn Daeng of Wat Hong Rattanaram and sent to China to produce glazed tiles, later used to decorate Wat Ratchabophit Sathitmahasimaram. (Phusadee Thapthas, Encyclopedia of Thai Culture – Central Region, Vol. 3, 1999: 1131, 1141)

13.3 Architecture What types of construction comprised architectural works during the Thonburi period?

During the reign of His Majesty King Taksin, it was an era of establishing and reorganizing settlements, leading to extensive construction works, including palaces, fortresses, city walls, and various temples. The architectural style of this period largely inherited elements from late Ayutthaya architecture. Building bases were gently curved like the hull of a ship, while the structures rose vertically. Other architectural components were not much different from those of Ayutthaya. Unfortunately, Thonburi-period architecture has often undergone restoration and renovation in later reigns. As a result, present-day appearances mostly reflect the style of the latest restorations. Structures that still retain some Thonburi architectural features include Wichaiprasit Fort, the walls of the former royal palace, the Thong Phra Rong and twin pavilions of the former palace, and temples in both the capital and provincial towns that were restored during this reign. Surviving Thonburi-era stylistic features can be observed in the ubosot and small vihara of Wat Arun Ratchawararam, the original ubosot and vihara of Wat Ratchakarah, the original ubosot of Wat Intaram, the Red Pavilion of Wat Rakhang Kositaram, and the ubosot of Wat Hong Rattanaram.

Note

1. Wat Arun Ratchawararam is located on the west bank of the Chao Phraya River and the east side of Arun Amarin Road, at the mouth of the Mon Canal, opposite Tha Tian Market. It is one of the most beautiful temples, showcasing Thai craftsmanship from the late Ayutthaya period to the Rattanakosin period.

History of the Temple

Wat Arun originally existed during the Ayutthaya period and was called Wat Makok, later renamed Wat Makok Nok, and eventually Wat Chaeng. It was elevated to a first-class royal temple during the reign of King Taksin because, when Ayutthaya fell to the Burmese, King Taksin, then Phraya Taksin, escaped by boat and arrived at the site of the temple at dawn, naming it Wat Chaeng. After securing independence in 1768, he established Thonburi as the capital, placing the royal palace within the walls of Wichaiprasit Fort on the west bank of the Chao Phraya River. The temple fell within the palace grounds, and monks were no longer permitted to reside there. During King Taksin’s 15-year reign, he restored the original ubosot and vihara of Wat Chaeng as much as possible (Fine Arts Department, 1978: 5-6).

Later, during the reign of King Rama II, further restorations and constructions were made, renaming the temple Wat Arun Ratchatharam. During King Rama IV’s reign, it was restored and renamed Wat Arun Ratchawararam, the official name used to this day.

Important Historical Structures at the Temple

Significant structures include the ubosot, showcasing Rattanakosin craftsmanship of King Rama IV’s era. In front of the ubosot entrance stand two guardian giants holding clubs, called Kumpan, believed to protect the temple from evil spirits. These figures demonstrate masterful craftsmanship, originally created by Phraya Hattakarn Bancha (currently restored inaccurately). The entrance doors feature crown-shaped arches, and the ubosot is surrounded by a cloister housing Buddha images in the Mara-victory posture. The principal Buddha image, named Phra Buddha Thammisara Ratchaloknathadilok, is gilded stucco, crafted during King Rama II’s reign, with a three-sok-wide lap. Notably, the Buddha’s face was modeled by the king himself. On either side sit two principal disciples in anjali posture. The interior walls feature murals depicting the Buddha’s life, and door panels are decorated with trompe-l’oeil patterns.

Another important structure is the vihara, housing the principal Buddha image, Champhunut Mahaburusalakkhana Asityanubhapitar, and in front, a smaller Buddha image called Phra Arun or Phra Chaeng, with a lap width of 50 cm, brought from Vientiane by King Rama IV. On the south side of the temple stand the original ubosot and small vihara, which are also of interest. The ubosot houses the platform used by King Taksin, made from a single wooden board, 1.67 meters wide. The small vihara enshrines the Phra That Chulamanee.

Another important historical structure is the prang of Wat Arun. King Rama II planned to rebuild the original prang, which was only 16 meters high, to be taller and more beautiful. Work began but King Rama II passed away before completion. King Rama III continued construction, completing the prang and installing the spire crown. The design and later decorative tiles were the work of Phraya Ratchasongkram (Kat Hongsakul) and his son, Phraya Ratchasongkram (Thad Hongsakul). Because construction spanned three reigns, the base and form of the prang were repeatedly restored up to the present (Natthaphat Navikcheewin, 1976: 57-58).

2. Wat Intharam, or Wat Bang Yi Ruea Nok

is a temple where King Taksin the Great performed royal merit-making activities. It houses several antiquities associated with him, such as the reclining royal bed platform, which served as the royal seat where he observed precepts and practiced meditation.

In addition, it is the burial site of King Taksin the Great. His cremation was conducted here, and his relics were enshrined at this temple as well. Today, Wat Intharam is classified as a third-class royal temple of the Worawihan type. It is located on Thoet Thai Road, Bang Yi Ruea Subdistrict, Thonburi District, Bangkok, covering an area of approximately 25 rai. The founder of the temple is unknown, but it is generally believed to be an ancient temple dating back to the Ayutthaya period.

According to local accounts, the area along Khlong Bangkok Yai, which was Bang Yi Ruea at that time during the Ayutthaya period, was a dense mangrove forest. The opposite bank was a lowland with grasses and reeds growing in shallow water, resembling a marsh. Boats navigating this canal had to make wide turns, allowing the forested area to be seen from a distance. This riverside forest became a strategic location for Thai soldiers to ambush enemy boats. The ambush tactic was called Bang Ying Ruea, which eventually gave the area its name, later becoming Bang Yi Ruea.

Wat Intharam was originally called Wat Bang Yi Ruea Nok, paired with Wat Ratchakaraha (Bang Yi Ruea Nai). When King Taksin established Thonburi as the capital, he was greatly pleased with this temple. He ordered extensive renovations and expansions, elevating it to a special first-class royal temple and using it for major royal merit-making ceremonies multiple times.

King Taksin granted a large area of land as sacred temple grounds. He built 120 monk’s quarters, restored statues, the ordination hall, pagodas, and assembly halls, and donated the Buddhist scriptures. He also renovated the entire temple complex and came to observe precepts and practice meditation in the royal residence here on five occasions. He used Wat Intharam as the site for royal cremation ceremonies and for enshrining the relics of Somdet Phanpi Luang, Princess Thepamat (Nok Yiang), the king’s mother. He ordered the construction of a crematorium, which took two months to complete, and had her body brought to Wat Intharam on Tuesday, the 2nd waning day of the 6th lunar month, in the year of the Ram, 2318 BE. The cremation took place two days later, on Thursday, the 4th waning day, and lasted three days and three nights. The ceremony included about twenty ceremonial pavilions, and around 6,000 monks and Brahmins were invited to make merit. At the same time, Burmese troops advanced close to Phitsanulok, which motivated the king to perform another merit-making ceremony for his mother.

In 2319 BE, King Taksin held another major royal merit-making ceremony for his mother. This grand event involved soldiers from other provinces, including Lopburi, Nakhon Sawan, Phichit, Phitsanulok, Kamphaeng Phet, Sukhothai, Chai Nat, Singburi, Ang Thong, Chachoengsao, Ratchaburi, Phetchaburi, and Suphanburi, who assisted in the temple ceremonies.

According to the schedule, on Tuesday, the 15th day of the waxing moon of the first lunar month in the Year of the Monkey, B.E. 2319, after the crematorium and the ceremonial site were completed, and after the royal relics were paraded from the Royal Palace past Wat Moli Lok (Wat Tai Talat) to Bang Yi Khan and then returned to be enshrined at the pavilion of Wat Intharam, the king ordered the Central Department to distribute money as great alms to all officials attending the ceremony. Men were granted salueng each, and women one fueang each. The king also instructed Phra Ya Maha Senakum to take 10 chang of money to distribute to beggars throughout both the capital and the provinces. The king further commanded the Sangha to invite 10,000 monks for the ceremonial meal. Among them, there were 2,230 monks and 1,738 novices (according to the account in the Thonburi Chronicles, Panjanumart edition, by Jerm, the monks did not differentiate by sect or temple). In King Rama V’s commentary, it was explained that “10,000 monks for the ceremonial meal” meant offering two bundles of rice to each monk, not money, which was the method used in the old capital.

Antiquities associated with King Taksin the Great

The Chedi Ku Chat is the stupa that contains the royal relics of King Taksin the Great. Its lotus finial stands paired with the stupa containing the royal relics of the queen. Both are enshrined in front of the old ordination hall.

The Buddha image in royal attire of King Taksin the Great is in the posture of enlightenment. It is the principal image in the old ordination hall and also houses the king’s cremated remains.

The bronze Buddha image in Mara-vijaya posture from the Ayutthaya period is enshrined in the small vihara next to the old ordination hall, also known as the Vihara of King Taksin the Great.

The old ordination hall, renovated by King Taksin the Great, originally had no windows. Later, when Phra Thaksin Kanishorn became the abbot, he opened windows in the walls.

The vihara houses the royal bed platform of King Taksin the Great and a model statue depicting him in meditation practice.

The new ordination hall was built over the area where King Taksin the Great’s royal relics are enshrined.

In addition, there are numerous prangs, stupas, and vihara structures that were constructed or restored after King Taksin’s reign. Some are now in ruins, while others are under renovation or newly built (Sanan Silakorn, 1988: 123–125)

13.4 Literature

In the late Ayutthaya period, after the reign of King Boromkotr, literature that had once flourished fell into decline once more. After the fall of Ayutthaya to the Burmese in 1767, the city was devastated and burned, which likely led to the destruction of many old books. Later, when King Taksin restored the unity of the nation, literature began to revive. However, the Thonburi period lasted only 15 years and was a time of rebuilding, so literary works were few. Those that did survive are almost all of significant value.

It is generally accepted that literature thrives during peaceful times, while in times of turmoil and war, literary activity declines. During King Taksin’s reign, the country faced numerous difficulties, yet he did not allow literature to decline accordingly. He actively resisted this deterioration, making the Thonburi period remarkably productive in literary creation.

Thonburi-era literature was directly influenced by the Ayutthaya period, using existing works as models for composition. Consequently, Thonburi literature closely resembled that of Ayutthaya. The characteristics of Thonburi-era literature are as follows:

1. All literary works were composed entirely in verse, employing all forms of poetic composition, including khlong, chan, kap, klon, and rai.

2. The content focused heavily on religion, moral teachings, glorifying the king, and entertainment.

3. Compositions often began with a prelude of praise or homage to show respect for revered subjects, followed by descriptive passages conveying emotions and sentiments. The emphasis was on beauty rather than content or philosophical ideas.

4. Thai values were clearly embedded, including respect, loyalty to the king, adherence to Buddhism, and the customs and traditions of Thailand (Uthai Chaiyanon, 2002: 8-9).

13.4.1 Who were the poets in the Thonburi period?

Poets in the Thonburi period, apart from King Taksin himself, were all government officials and senior monks whose names are recorded as follows:

1. Phra Wanarat (Thongyu), who later became the royal preceptor of King Buddha Loetla Nabhalai and left the monkhood to serve as Phraya Pojanapimon.

2. Phra Phimoltham of Wat Photaram (Wat Phra Chetuphon), who later became the royal preceptor of Prince Paramanujita Jinorasa and was afterwards elevated to Somdet Phra Wanarat.

3. Phra Rattanamuni (Kaew), who later left the monkhood to serve as Phraya Thammapreecha, founder of the Raktaprajit family.

4. Nai Suan Mahat Lek, who composed Khlong Yo Phra Kiat in praise of King Taksin in 1771.

5. Luang Sorawichit (Hon), a border officer in Uthai Thani, who later became Chaophraya Phraklang (Hon), Minister of the Port Department during the reign of King Rama I. He composed Phet Mongkut, using the tale Vetala Pakornnam as the narrative framework (the episode in which the Vetala tells a riddle tale of Prince Phet Mongkut), as well as Inao Khamchan. He passed away in 1805.

6. Phraya Mahanupap (On), who composed Nirat Kwangtung during his journey to China in 1781, a work of significant historical value as it records the events and experiences of the voyage; he also wrote three lyrical poems.

7. Phra Phikku In of Nakhon Si Thammarat, who composed Krissana Son Nong in collaboration with Phraya Ratchasuphavadi (Veena Rotjanaratha, 1997: 99).

8. Phraya Ratchasuphavadi, formerly the head of the Suratsawadi Department in Ayutthaya, who had been appointed by King Ekkathat as governor of Nakhon Si Thammarat, though the exact year of his appointment is unknown. He was said to be one of the great poets under King Borommakot and lived on into the Thonburi period. While serving as governor of Nakhon Si Thammarat, he was charged with wrongdoing and summoned back to Ayutthaya to stand trial, eventually losing the case and thus being removed from office in 1765. Later, he served as a minister and royal commissioner of Nakhon Si Thammarat (from 1769–1776, a total of seven years). During the tenure of Chao Nara Suriyawong as governor of Nakhon Si Thammarat, he served in a supporting administrative role; when Chao Nara Suriyawong passed away, he was recalled to Ayutthaya to resume government service (http://www.navy.mi.th/navy88/files/Nakorn.doc, 31/03/2004) (Royal Biography and Royal Activities of King Taksin of Thonburi: Cremation Ceremony for Miss Phan Na Nakhon, 20 September 1981: 8).

13.4.2 What literary works did King Taksin the Great compose?

The Royal Compositions of King Taksin the Great

King Taksin was more a warrior and a savior of the nation than a poet, for his reign was filled with warfare. However, he was a farsighted ruler who recognized the value of literature, and thus devoted his spare time to composing an important literary work, the Ramakien. The surviving portions of his royal compositions include episodes of the Ramakien: Hanuman entering the chamber of Lady Vanarin, the fall of Virunchambang, King Maliwarat adjudicating the case, Tosakan performing the ritual of burning the divine effigy, the casting of the Kabinphat spear, Hanuman tying the hair of Tosakan and Lady Mandodari together, and the releasing of the horse Uppakara. In addition, there are official documents from his reign that he corrected or composed, such as royal letters, formal correspondence, decrees, various regulations, the Treatise on Military Strategy, manuals on weapon making, didactic verses, administrative customs, and civic traditions.

The Ramakien was written in black Thai folding books, with the script executed in gold lines, crafted with exceptional refinement. According to the title folios, the date of composition is recorded at the beginning of every volume: Sunday, the first waxing day of the sixth lunar month, Chula Sakarat 1132, the Year of the Tiger, the second cyclical year, which corresponds to 1770, the third year of his reign. Later, scribes recopied the original royal manuscript according to his revisions, but retained the original title folios, resulting in the phrase “tram phodi yu” appearing in the extant Thai manuscripts. The time when the gold lines were applied is recorded as “Sunday, the eighth waning day of the twelfth lunar month, Chula Sakarat 1142 (1780),” near the end of his reign. The names of the four scribes who applied the gold are given as Nai Thi for volume 1, Nai Sang for volume 2, Nai Son for volume 3, and Nai Bunchan for volume 4. The names of the two donors, identical in every volume, are Khun Saraprasoet and Khun Mahasitthi. Unfortunately, the original manuscript written by the King himself has not been found (Uthai Chaiyanon, 2002: 15).

A depiction of the Ramakien, showing the episode in which Hanuman stretches himself into a bridge for Prince Phra Phrot’s army to cross the ocean and return to Ayutthaya, 1930

Powder pigments, mural painting, Room 154, Gallery of Wat Phra Si Rattana Satsadaram, Grand Palace, Bangkok

By the artist Suang Thimudom (image from Rattanakosin Art, Reigns I–VIII, Volume 1)

The origin of this royal composition derives from the King’s march south to suppress the faction of the Lord of Nakhon Si Thammarat in 1769. On that occasion, the Lord of Nakhon and his important associates and relatives fled to Thepha (now in Songkhla Province). The royal army pursued them.

The Memoirs of Krom Luang Narintorn Devi recount this episode as follows:

“When Phrarit Deva, the ruler of the city, learned that the royal army was in pursuit, he feared the royal authority and sent the Lord of Nakhon together with his relatives and followers, as well as the female performers, silver ornaments, royal treasures, and various possessions, to be presented immediately.”

This means that, apart from capturing the Lord of Nakhon, the most significant figure, they also gained female performers as an additional result.

While the Thonburi army was stranded by the monsoon in Nakhon Si Thammarat and unable to return to the capital for several months, in the twelfth month of that year, King Taksin performed royal merit-making ceremonies to celebrate the sacred relics of Nakhon Si Thammarat, and also commanded the female performers of the Lord of Nakhon to participate in the celebration. This pleased the King greatly and sparked his strong interest in theater from that time onward, leading him to train and revive it in Thonburi, as reflected directly in the fields of dance and music.

Just one month after returning from Nakhon Si Thammarat, he diligently composed the Ramakien play, having only two months for this work, because thereafter he had to lead a campaign to suppress the faction of Chao Phraya Fang in Uttaradit in the sixth month of early 1770.

He used very little time for composing such a high literary work, so it is natural that there would be some imperfections, lack of conciseness, and occasional lapses in elegance. This Ramakien play was directly composed by King Taksin himself, not mediated through any other poet (as in the Ramakien of King Rama I). Therefore, this royal composition reflects his character and wisdom very clearly (Sethuen Supasopon, 1984: 76). In the sixth month of 1770, he also received a report from the Uthai Thani provincial office regarding the misconduct of Chao Phraya Fang’s followers. By the eighth month of the same year, he led the royal army to suppress them. Thus, King Taksin likely completed all four episodes of the composition during this period, though he may have made later corrections, as indicated by inserted phrases in some sections such as “yang (tram, phodi) yu” or “inserted by the King.” If the composition had been completed before attacking Chao Phraya Fang, it might have been used in the celebratory performances when Sawangkhaburi was conquered (according to the Memoirs of Krom Luang Narintorn Devi: “Let the female performers be brought to celebrate Phraya Fang for seven days, then proceed to tread Phitsanulok

The celebration of Phra Chinarat and Phra Chinsri for seven days, with female performers,” may have used the Ramakien play staged according to the royal composition of King Taksin.

That a monarch devoted himself to poetry, even composing works while scarcely able to take time away from military duties, served as inspiration for other talented poets of the era to create works, even though the country had not yet fully returned to peace and normalcy.

Purpose of Composition

The purposes of composing the Ramakien may be outlined as follows:

1. To continue the royal tradition of promoting literature, with the monarch himself as the author.

2. To provide entertainment and enjoyment for the people.

3. To revive and preserve the Ramakien, an important literary work dating back to the Ayutthaya period.

4. To select episodes containing moral lessons suitable for guiding and comforting the people at that time, and additionally, to incorporate elements of meditation, in which the King had great interest, thus encouraging the people to practice for inner peace.

5. To compose a royal play for court performances, which customarily featured the Ramakien. According to the historical chronicle Phan Chanumas (Jerm), when King Taksin led the army to conquer Nakhon Si Thammarat in 1769, he brought back the Lord of Nakhon along with female performers to establish a royal theater, necessitating the composition of the play for performance (Kularb Mallikamas, Thai Literature: Ramkhamhaeng University, n.d.: 24–25).

The title folio of the original Thai folding book of this literary work states that King Taksin composed it in Chula Sakarat 1132 (1770). It is a verse drama with the names of the songs and dance sequences fully indicated, comprising four episodes (four volumes of Thai folding books) as follows:

Episode 1: Phra Mongkut – This is the final episode of the Ramakien and was composed as the first royal manuscript. The story concerns Phra Mongkut and Phra Lop, the sons of Rama and Sita, who are in the forest with the sage Valmiki because Sita has been exiled. The sage gives magical arrows to the two princes. The princes test the thunderous arrows by sending them to Ayutthaya. Rama releases the horse Uppakara to demonstrate his power. Phra Mongkut and Phra Lop ride the horse for fun. Phra Phrot captures Phra Mongkut to present to Rama, and Phra Lop follows to rescue him, and they escape together. The episode ends with Rama leading the army to pursue the two princes.

Episodes 2–4 are continuous in content as follows:

Episode 2 concerns Hanuman wooing Lady Vanarin. The beginning of the text is missing, so the episode starts with Hanuman meeting Lady Vanarin in the water (Lady Vanarin is a fairy who was cursed and must guide Hanuman to kill Virunchambang to break the curse). Hanuman wins her as his wife, then kills Virunchambang successfully, and returns to take her to the city of Fa. Tosakan orders her to summon King Maliwarat to Lanka to assist him. Episode 2 ends with King Maliwarat arriving at the battlefield but refusing to enter Lanka.

Example:

Hanuman woos Lady Vanarin

“This lady, foremost among maidens, a celestial of unmatched grace,

Do not doubt; I shall make it clear, only a little patience, O maiden.”

Episode 3 concerns King Maliwarat adjudicating with impartiality, bringing the plaintiff, the defendant, and Lady Sita to the battlefield, ruling that Tosakan must return Lady Sita. Tosakan refuses, and King Maliwarat curses him.

Episode 4 concerns Tosakan performing the sand ritual and consecrating the spear Kabinphat. Lady Mandodari incites Tosakan to kill Phiphek, who has been secretly informing Rama’s side. Phiphek hides and protects Phra Lak, who then uses the spear Mokkhasak. Hanuman flies to fetch the antidote, while Mae Hin grinds the medicine in Naga city and Luk Hin remains in Lanka. Tosakan lies down to sleep; Hanuman subdues him, breaks the top of the palace to seize Luk Hin, and then mischievously ties Tosakan’s hair to Lady Mandodari’s. Tosakan cannot untie it and must summon the sage Kobut to undo it.

Example:

Hanuman ties Tosakan’s hair to Lady Mandodari

“Having performed the final acts of renunciation, the diamond wisdom is of no use,

With power and mental skill, together with spiritual insight, recalling past and future lives,

Upon reaching that point, all will perish; not a single thing remains intact…”

Episode: The Battle of Pali and Tosakan

Pali recited incantations and summoned the forces of the demons,

According to the blessing of the Lord of the Three Worlds, contending in the demon war (2 words).

Tosakan lost half his strength, resisting in the battle of glory,

Hungry and exhausted, the demons flew back to the city of Lanka (2 words).

General Characteristics of the Ramakien Drama

The royal composition of the Ramakien is a verse drama in the old Ayutthaya poetic style, with complete songs and dance sequences for each episode. Its general characteristics are as follows:

- It uses simple, common words throughout the story, suitable for performance as a play for the general audience, for example, in the verse:

คิดแล้วให้สืบเทวา ตามตำรามาแถลงไข

เทวาจะว่าประการใด จงเร่งให้การมา

ฝ่ายทศกัณฐ์โจทก์ค้าน พยานเหล่านี้ชังข้างข้า

ไม่รู้ว่าได้ษีดา มาเป็นพยานมิเต็มใจ

ฝ่ายเทพรับสมอ้างค้าน สบถสาบานแถลงไข

แม้นมุสาให้ข้าบรรลัย มิได้เอาเท็จมาเจรจา

ชังจริงด้วยเธออาธรรม ถึงกระนั้นก็ไม่มุสา

ไม่แจ้งว่าได้ษีดา ข้ามิได้เอาเท็จมาพาที

เดิมข้าได้ยินเขาลือเลื่อง ในเมืองพระชนกฤาษี

เธอกลับเข้าครองบุรี ทำการพิธีมงคล

ให้ตั้งธนูยกศิลป์ชัย ชวนกันลงไปทุกแห่งหน

ใครยกไหวจะได้เนียรมล ผู้คนเต็มไปทั้งพารา

The verse style in the royal composition predominantly uses ordinary, common language, so that in some parts it resembles folk drama of earlier times, such as the episode of King Maliwarat listening to Tosakan’s distorted explanation about abducting Lady Sita from Rama.

เมื่อนั้น พระบรมลักษมณ์ศักดิ์สิทธิ์

ได้ฟังพ่ออ้ายอินทรชิต บิดผันเศกแสร้งเจรจา

เป็นสิ่งของหรือตกหล่น นี่มาเก็บคนได้กลางป่า

ผิดที่มิเคยพบเห็นมา หรือว่าผู้อื่นลักนาง

พอพบพระยาอสุรี ถ้าฉะนี้จะเห็นด้วยบ้าง

เกรงกลัวคิดว่าผัวนาง ขว้างเสียทิ้งไว้หนีไป

อันกระนั้นมั่นแม่นผิดที่ ถ้าฉะนี้พอจะเห็นด้วยได้

นี่สิว่านางตกกลางไพร จนใจไม่รู้ที่เจรจา ฯลฯ

These royal compositions reveal a quick, energetic temperament, fearless of anyone, straightforward in speech, disliking circumlocution, yet enjoying playful use of language at times.

In many passages, the wording is forceful and direct, blunt like an axe, using plain, folk-style language that expresses emotions openly and sincerely, especially in scolding or admonishing scenes, such as at the end when King Maliwarat berates Tosakan for giving false testimony regarding the abduction of Lady Sita from Rama.

เมื่อนั้น พระทรงทศธรรมรังษี

เดือดด่าพญาอสุรี อ้ายนี่มันช่างเจรจา

ฝ่ายมึงลักเมียเขาพรากผัว จะช่วยชั่วกระไรอ้ายบ้า

เมื่อเอ็งเล็ดลอดลักมา จะเห็นหน้าตามึงกลใด

มาดแม้นถ้าพบเจ้าผัว โดยชั่วไม่ละเมียให้

เช่นนี้หรือนางตกกลางไพร จะพิพากษาให้มึงมา ฯลฯ

In another episode, when King Maliwarat counsels and comforts Tosakan, he not only uses strong, plain, everyday language to admonish and instruct, but also interjects playful humor involving women shooting arrows at boats.

จงฟังคำกูผู้ปู่สอน ให้ถาวรยศยิ่งภายหน้า

จะทำไมกับอีษีดา ยักษาเจ้าอย่าใยดี

มาดแม้นถึงทิพสุวรรณ สามัญรองบทศรี

ดั่งฤาจะสอดสวมโมลี ยักษีอย่าผูกพันอาลัย

หนึ่งนวลนางราชอสุรี ดิบดีดั่งดวงแขไข

ประโลมเลิศละลานฤทัย อำไพยศยิ่งกัญญา

ว่านี้แต่ที่เยาว์ๆ ยังอีเฒ่ามณโฑกนิษฐา

เป็นยิ่งยอดเอกอิศรา รจนาล้วนเล่ห์ระเริงใจ

แม้นเจ้ามิฟังคำกู จะไปสู่นรกหมกไหม้

ล้วนสาหัสฉกรรจ์บรรลัย จะใยดีอะไรกับษีดา ฯลฯ

The composition does not favor vowel rhyming, retaining ordinary spelling in accordance with the convention of the Ayutthaya period.

เมื่อนั้น ท้าวทรงจตุศีลยักษา

ครั้นเห็นนวลนางษีดา เสน่หาปลาบปลื้มหฤทัย

อั้นอัดกำหนัดในนาง พลางกำเริบราคร้อนพิสมัย

พิศเพ่งเล็งแลทรามวัย มิได้ที่จะขาดวางตา

ชิชะ โอ้ว่าษีดาเอ๋ย มางามกระไรเลยเลิศเลขา

ถึงนางสิบหกห้องฟ้า จะเปรียบษีดาได้ก็ไม่มี

แต่กูผู้รู้ทศธรรม์ ยังหมาย มั่นมุ่งมารศรี

สาอะไรกับอ้ายอสุรี จะมิพาโคติกาตาย..

- It incorporates knowledge and ideas of Vipassana meditation, indicating that while composing, the King was studying or had begun practicing Vipassana, as in the episode where the sage Kobut speaks to Tosakan:

พระมุนีจึงว่าเวรกรรม มันทำท่านท้าวยักษี

อันจะแก้ไขไปให้ดี ต่อกิจพิธีว่องไว

จึงจะสิ้นมลทิลบาปหยาบหยาม พยายามอนุโลมลามไหม้

ล้างลนอกุศลสถุลใจ เข้าไปในเชาวน์วิญญาณ

เป็นศีลสุทธิ์วุฑฒิ หิริโดยตะทังคะประหาร

คือบทแห่งโคตระภูญาณ ประหารโทษเป็นที่หนึ่งไป

A special characteristic, considered unique and rarely found in other versions of the Ramakien, is that King Taksin’s royal composition contains many passages emphasizing morality and miraculous powers, reflecting his wisdom and royal disposition, with a strong dedication to Dhamma as well as the practice of Samatha and Vipassana meditation.

When describing the episodes of King Maliwarat, he often uses phrases such as “the righteous king of virtue,” “the king who performs virtuous deeds,” “the king radiant with the ten virtues,” “the king radiant with moral virtue,” or “the king endowed with the four precepts,” etc. Some passages seem to incorporate the King’s personal routines, for example, in the episode describing Lord Shiva sitting to discuss Dhamma with the sage:

One day he sat, still upon the radiant throne,

Discussing profound Dhamma with the sage Narot.

This royal composition reflects King Taksin’s disposition, devoted to the study of moral and philosophical teachings. In his leisure time, he took pleasure in discussing Dhamma with the Sangha or even with clerics of other religious traditions, such as French missionaries or Islamic teachers, as recorded in various chronicles and royal annals.

In the episode where Lady Mandodari comforts Tosakan, disappointed that King Maliwarat refused to side with him, the composition skillfully incorporates moral teachings.

พระจอมเกศแก้วของเมีย ปละอาสวะเสียอย่าหม่นไหม้

แม้จิตไม่พิทราลัย ถีนะมิทธะภัยมีมา

อันซึ่งความทุกข์ความร้อน ตัวนิวรณ์วิจิกิจฉา

อกุศลปนปลอมเข้ามา พาอุธัจจะให้เป็นไป

ประการหนึ่งแม้นมีเหตุ เวทนาพาลงหมกไหม้

ฝ่ายซึ่งการแพ้ชนะไสร้ สุดแต่ได้สร้างสมมา

ถึงกระนั้นก็อันประเวณี ให้มีความเพียรจงหนักหนา

กอปมนตร์ดลทั้งอวิญญาณ์ สัจจะสัจจาปลงไป

ล้างอาสวะจิตมลทิน ให้ภิญญโญสิ้นปัถมัย

เมียเขาเอามันมาใย ไม่ควรคือกาลกินี ฯลฯ

Especially in the episode where the sage Phra Kobut teaches Tosakan, it clearly reflects the King’s profound wisdom in advanced Dhamma, containing extensive terminology related to high-level teachings. In addition, it also demonstrates miraculous powers arising from the practice of Dhamma.

พระมุนีจึงว่าเวรกรรม มันทำท่านท้าวยักษี

อันจะแก้ไขไปให้ดี ต่อกิจพิธีว่องไว

จึงจะสิ้นมลทินบาปหยาบหยาม พยายามอนุโลมลามไหม้

ล้างลนอกุศลสถุลใจ เข้าไปในเชาว์วิญญาณ

เป็นศีลสุทธิ์วุฑฒิ หิริโดยตะทังคะประหาร

คือบทแห่งโคตระภูญาณ ประหารโทษเป็นที่หนึ่งไป

แล้วจึงทำขึ้นที่สอง โดยเนกขัมคลองแถลงไข

ก็เป็นศิลาทับระงับไป อำไพพิลึกโอฬาร์

อย่าว่าแต่พาลโภยภัย ปืนไฟไม่กินนะยักษา

ทั้งหกสวรรค์ชั้นฟ้า จะฆ่าอย่างไรไม่รู้ตาย

อย่าคณนาไปถึงผู้เข่นฆ่า แต่วิญญาณ์คิดก็ฉิบหาย

จะทำอย่างใดไม่รู้ตาย อุบายถอยต่ำลงมา

อันได้เนกขัมประหารแล้ว คือแก้ววิเชียรไม่มีค่า

ทั้งฤทธิ์และจิตตวิชชา อีกกุพนามโนมัย

กอปไปด้วยโสตประสาทญาณ การชาติหน้าหลังระลึกได้

ถึงนั่นแล้วอันจะบรรลัย ไม่มีกะตัวถ่ายเดียว

อย่าประมาณแต่การเพียงนี้ สามภพธาตรีไม่คาบเกี่ยว

สาบไปแต่ในนาทีเดียว มิทันเหลียวเนตรอสุรา

จะสาอะไรกับรามลักษณ์ ถึงไตรจักรทั่วทศทิศา

ไม่ครั่นครือฤทธิ์วิทยา ถ้าปรารถนาเจ้าเรียนเอา ฯ

In this royal composition, King Chulalongkorn (Rama V) commented:

“The text arranged here clearly reveals the mind of King Taksin, showing great courage in his knowledge and delight in the practice of Dhamma meditation; such is the form of his thinking.”

In another comment, he noted:

“…the parts corrected by King Taksin mostly appear in the battle episodes and in matters of miraculous powers within Dhamma practice.”

It is a play with a tightly structured plot, keeping pace with the actors’ movements, as in the episode where Hanuman battles Virunchambang.

ฝ่ายวิรุณจำบังตกใจ ก็รู้ว่าภัยมาตามผลาญ

จึงอ่านพระเวทวิชาการ บันดาลแทรกตัวออกมา

พ้นจากวงหางขุนกระบี่ อสุรีอายใจยักษา

ก็ผาดโผนแผลงฤทธา กลับเข้าเข่นฆ่าหนุมาน

หนุมานเผ่นโผนโจนจับ จับกุมกันตามกำลังหาญ

วิรุณจำบังตีหนุมาน พลังทานมิได้จมไป

หนุมานผุดขึ้นอ่านมนต์ เข้าผจญชิงเอากระบองได้

วิรุณจำบังจมไป ผุดเมื่อไรซ้ำตีอสุรา

The book “Collection of Examples of Royal Composed Verses” by the Vajirayan Library explains at the end of King Taksin’s royal composition: “It is said that composing plays was very difficult for King Taksin. It is told how he composed so that it could be sung and danced exactly as in his royal composition. Sometimes the original verses could not be sung, which made him angry. King Chulalongkorn once mentioned in his book of royal commentary that ‘King Taksin’s composition differed greatly from this. It is said that many parts were so forceful and boisterous that he was almost furious. The verses that had to be whipped and struck were many, such as in the scene presenting the monkeys:

“Used by day, used by night, sitting by the lamp watch, striking armor, knocking wood, unable to stay, so they fled.”

5. The content is relatively short and concise because the King focused primarily on the story, avoiding lengthy, drawn-out embellishments, unlike the Ramakien royal composition of Rama I, which is widely known. For example, one episode in King Taksin’s version contains only 146 words, while in Rama I’s composition, it contains 400 words. Comparing printed pages, King Taksin’s version occupies only 11 pages, whereas Rama I’s version fills 50 pages.

This demonstrates the King’s brisk temperament, disliking delays, taking pleasure in speaking directly, focusing on delivering the matter efficiently, and thus prioritizing content and narrative above all.

The expansion in Rama I’s version, using elaborate rhetorical flourishes, has led some scholars to suggest that poets assigned to compose certain episodes may have used King Taksin’s version as a base, merely enlarging the content.

For this reason, the story is essentially the same, but the number of verses is multiplied many times over.

6. In several episodes, King Taksin also expresses poetic emotion and aesthetic sensibility. For example, in the episode where King Maliwarat admires Lady Sita’s beauty, he can use descriptive rhetoric in a strikingly vivid manner. This royal composition is relatively long, as illustrated in the following example:

เมื่อนั้น พระทรงจตุศีลยักษา

ครั้นเห็นนวลนางษีดา เสน่หาปลาบปลิ้มหฤทัย

อั้นอัดกำหนัดในนาง พลางกำเริบราคร้อนพิสมัย

พิศเพ่งเล็งแลทรามวัย มิได้ที่จะขาดวางตา

ชิชะโอ้ว่าษีดาเอ๋ย มางามกระไรเลยเลิศเลขา

ถึงนางสิบหกห้องฟ้า จะเปรียบษีดาได้ก็ไม่มี

แต่กูผู้รู้ทศธรรม์ ยังหมายมั่นมุ่งมารศรี

สาอะไรกับอ้ายอสุรี จะมิพาโคติกาตาย

โออนิจจาทศกัณฐ์ สู้เสียพงศ์พันธุ์ฉิบหาย

ม้ารถคชพลวอดวาย ฉิบหายเพราะนางษีดา

ตัวกูผู้หลีกลัดตัดใจ ยังให้หุนเหี้ยนเสน่หา

ที่ไหนมันจะได้สติมา แต่วิญญาณ์กูแดยัน

ขวยเขินสะเทินวิญญาณ์ กว่านั้นไม่เหลือแลแปรผัน

ไม่ดูษีดาดวงจันทร์ พระทรงธรรม์เธอคิดละอายใจ

บิดเบือนพักตร์ผินไม่นำพา ขืนข่มอารมณ์ปราไส

อัดอั้นอดยิ้มไม่ได้ เยื้อนแย้มว่า ไปแก่ษีดา

เจ้าผู้จำเริญสิริภาพ ปลาบปลื้มเยาวยอดเสน่หา

เจ้าเป็นเอกอรรคกัญญา หน่อนามกษัตราบุรีใด

ทำไมจึ่งมาอยู่นี่ สุริวงศ์พงศ์พีร์อยู่ไหน

ลูกผัวเจ้ามีหรือไม่ บอกไปให้แจ้งบัดนี้

In some episodes, he skillfully incorporates humor, such as when Tosakan converses with Lady Mandodari, his consort, about burning the celestial image. The royal composition is as follows:

ฝ่ายพี่จะปั้นรูปเทวา บูชาเสียให้มันม้วยไหม้

ครั้นถ้วนคำรบสามวันไซร้ เทวัญจะบรรลัยด้วยฤทธา

ไม่ยากลำบากที่จะปราบ ราบรื่นมิพักไปเข่นฆ่า

พี่ไม่ให้ม้วยแต่นางฟ้า จะพามาไว้ในธานี

What has been mentioned so far represents only a portion of the insights. There remain many passages worthy of study and admiration, reflecting the royal diligence with which He composed this drama amidst the chaos of war and the manifold disturbances of the kingdom. Nevertheless, His compositions retain remarkable literary value.

Thanit Yu Pho, former Director-General of the Fine Arts Department and an expert in performing arts and drama, provided valuable insights regarding King Taksin’s Ramakien compositions in his 1941 article “Telling the Story of the Ramakien.” One significant passage reads:

“In summary, the wording, verse style, literary techniques, and the portrayal of characters in this Ramakien are like a clear mirror, reflecting the King’s disposition and temperament in composing it. He appears to have been open, straightforward, and decisive, favoring swiftness and clarity, as can be seen even in the structuring of the scenes. He was bold, courageous, and willing to take risks calmly in critical situations. At the same time, he could create enjoyment alongside serious endeavors, showing a disposition that delighted in contemplating high moral and philosophical truths, unwilling to settle for mediocrity—either fully attaining what he sought or rejecting it completely, rather than accepting only partially.

This can be seen even from the form of the verses and the brevity of the acts, suggesting that His disposition was truly suited to the qualities required of a leader at that time… etc.

From the Ramakien drama as discussed here, it is evident that King Taksin was not only a skilled warrior but also a learned sovereign poet, possessing remarkable intellect and literary ability. (Setuean Supasopon, 1984: 76-80; Somphan Lekhapan, 1987: 24-26)

Value

1. Linguistic value: Uses simple, easy-to-understand words; the verse structure is concise, straightforward, fast-paced, and serious. It may not sound very gentle, but in love passages, it uses tender expressions.

2. Religious and moral value: Provides useful moral lessons for daily life, such as appreciating ordination and practicing Dharma to achieve spiritual results (Uthai Chaiyanon, 2002: 8).

13.4.3 What type of verse and length did Nai Suan Mahadlek use in composing “Khlong Yo Phra Kiat Somdet Phra Chao Krung Thonburi,” and what was its subject?

Nai Suan Mahadlek was a royal court official during the Thonburi period, though his full biography is unknown. From the literary work “Khlong Yo Phra Kiat Somdet Phra Chao Krung Thonburi,” it is evident that he served closely with the king even before the founding of the capital, being well-informed about important events and fully understanding the king’s character and behavior. He composed a valuable literary work as a tribute: “Khlong Yo Phra Kiat Somdet Phra Chao Krung Thonburi.” It is written entirely in four-line khlong (khlong si supap), consisting of 85 stanzas. The content of each khlong demonstrates the author’s clear recognition of King Taksin’s brilliance and is filled with loyalty.

This collection of khlong is praised as one of the most beautiful, suitable for a royal tribute. Reading it not only provides literary enjoyment but also offers historical knowledge and insights, serving as an important source for investigating events in early Thonburi. Nai Suan praises Thonburi as follows:

ดูดุจเทพแท้ นฤมิต

ฤาวิษณุกรรมปลิด จากฟ้า

ถ่อมถวายมอบสิทธิ์ ทรงเดช

เลอวิไลงามหล้า เลิศล้ำบุญสนอง

Nai Suan Mahadlek composed this royal tribute khlong in B.E. 2314, the 4th year of King Taksin’s reign, during the period when the king had just successfully reunified the Thai kingdom and was preparing to expand his military power and extend the royal territories, aiming to bring the formerly tributary states back under Thonburi’s rule.