King Taksin the Great

Chapter 7: The War to Restore Independence from Burma

7.1 The war to restore independence led by King Taksin the Great was a war in which he had to fight against or suppress which groups?

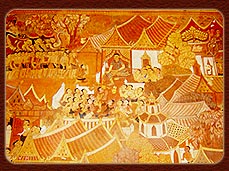

Chao Tak established his base in the eastern provinces, assembling troops, equipment and weaponry to prepare for leading his army back to reclaim the country from the Burmese forces (image courtesy of Muang Boran).

Chao Tak seized Chanthaburi on Sunday, 14 June 1767. Later, he also captured Trat, thus gaining complete and undisputed authority over the eastern provinces. During this period, several officials from Ayutthaya came to join him, most notably Luang Sak Nai Wero Mahadlek and Nai Sut Chinda (later the Front Palace Prince Maha Sura Singhanat in the reign of King Rama I of the Rattanakosin Kingdom). They also brought Nang Nok Iang, the mother of Chao Tak, from Ban Laem in Phetchaburi (Chusiri Chamroman, 1984: 93). Chao Tak’s paramount mission was to restore Ayutthaya to full independence. Considering the situation at that time, he must have deliberated intensely, for the principal forces he had to fight and suppress consisted of five groups: Suki, the Burmese commander at Pho Sam Ton, along with four other Thai factions.

However, after Chao Tak assessed the urgency, the action that had to be carried out immediately was the destruction of the Burmese force at Pho Sam Ton. Once he resolved to act, the war plan was formed, the primary objectives being: 1. Fort Vichai Prasit at the city of Thonburi; 2. to seize the Pho Sam Ton camp at Ayutthaya (at that time within Bang Pahan district).

The preparation of personnel, weapons, equipment, provisions, and the construction of more than one hundred war vessels took only a little over three months. Chao Tak’s fleet included junks (some of which had been seized from Trat), Iam Chun boats, rowboats, sailing boats, and pole-driven boats used for ascending the Chao Phraya River, along with various other types capable of navigating along the coast. The war fleet assembled at the mouth of the Chanthaburi River, with Chao Tak serving as admiral, must have been a most impressive and noteworthy sight.

Chao Tak led the army to destroy the Burmese force at the Pho Sam Ton camp (image courtesy of Muang Boran)

The condition of the Samet Ngam ship during the 1982 excavation showed that parts of the wooden hull had been dismantled by local villagers and piled on the shore, while other pieces were left scattered about (photo from Silpa Wattanatham Journal)

Saiyan Praichanchit (1990: 64-74) discussed an important archaeological site related to a vessel presumed to have been used by King Taksin in restoring independence, stating that Samet Ngam was an ancient junk discovered by villagers at Ban Ko Samet Ngam on the eastern bank of Khlong Ao Khun Chai (the Chanthaburi River) in 1980, and it was believed to be King Taksin’s shipyard. The discovery was reported to the Fine Arts Department in 1981.

The Fine Arts Department conducted a survey and built an earthen embankment enclosing the site, naming the vessel Samet Ngam after the locality where it was found. In 1989 the Underwater Archaeology Project and the Advanced Training Committee for Underwater Archaeology, a collaboration between the Fine Arts Department and SPAFA, carried out another excavation of the wreck to obtain further information and to study the ship’s structure in detail. The initial results of the excavation, study and analysis of the contextual evidence indicated that the Samet Ngam wreck was likely related to the preparations for assembling a naval force for King Taksin’s campaign to restore the nation.

The preparations for assembling a military force to restore the nation at Chanthabun by King Taksin are scarcely detailed in documentary evidence. Even the Phanchanumat (Choem) version of the Thonburi Chronicles, considered more reliable than other documentary sources, mentions only briefly that the king led a naval and land force to attack the guild of junk traders at Thung Yai (Trat) and won a decisive victory, after which Chien Chiam, their leader, submitted and presented his daughter as a consort. When he returned to Chanthabun, he ordered preparations for the army, including the construction of numerous war vessels. The same chronicle records that at that time he returned to Chanthabun and remained there while one hundred warships were built. It may therefore be said that King Taksin introduced a new form of naval force for use against the Burmese, and that the form and composition of his fleet differed from those of the Ayutthaya navy, for the crucial factor in movement was…

The second excavation of the Samet Ngam ship in March–April 1989 was carried out by the Underwater Archaeology Project and the participants of SPAFA’s underwater archaeology training course (ST-141a) (photo from Silpa Wattanatham Journal)

He employed junks as combat vessels as well. An interesting question concerns what type and size of warships he ordered to be built that could be produced in numbers exceeding one hundred within only three to four months. When considering the account in the same chronicle, which records events after the establishment of Thonburi as the capital, it states that when he led the naval force to attack the Burmese at Bang Kung in the Chulasakarat year 1130 (1768), he travelled aboard the royal barge Suwannamahapichai Nawa, a long boat (with an animal-headed prow) measuring 11 wa in length and a little over 3 sok in width, powered by 28 oarsmen. Later, when he marched to attack Phuthai Mat in Chulasakarat year 1133 (1771), following the same sea route used when advancing from Chanthabun to drive out the Burmese at Thonburi, he used the royal junk Samphao Thong together with 200 war vessels and another 100 junks. There can therefore be no doubt that the more than one hundred warships he had ordered to be built were long boats propelled by rowers or oarsmen.

A photograph of the second excavation of the Samet Ngam ship conducted in March–April 1989 (photo from Silpa Wattanatham Journal)

A map showing the route of navigation from Chanthabun to Ayutthaya (image from the book Boats: The Culture of the Chao Phraya River Basin and from Silpa Wattanatham Journal)

A line drawing of a junk in a seventeenth-century Japanese historical document; it is assumed that the Samet Ngam junk would not have differed significantly from this vessel (photo from Silpa Wattanatham Journal)

But for the sea march from Chanthabun to Thonburi, junks must certainly have been used as well, gathered from Chinese junk traders who were numerous in the coastal regions of Chanthaburi and Trat, and then repaired and modified to strengthen them and make them suitable for naval use. Evidence uncovered from the investigations of the Samet Ngam ship site since 1981 suggests that…

- 1. The Samet Ngam vessel was a Chinese junk (a small junk presumed to have been built in and brought from China. It had three masts and used a central stern-mounted axial rudder. Its overall length was about 12 wa (24 meters) and its beam about 4 wa (8 meters))

- 2. The vessel had been abandoned on the stocks in a repair yard around the twenty-fourth Buddhist century (approximately the late 1700s)

- 3. The repairs were left unfinished. A point of interest is whether the repairs were halted because the craftsmen lacked sufficient time, or because the vessel was too badly damaged to be made seaworthy again

The most likely explanation is that the craftsmen did not have enough time, since the period available for altering or repairing the vessels was limited, the number of vessels brought in for repair or modification was large, and there were already enough usable ships; thus this vessel was left unfinished on the repair stocks thereafter.

Note: Luang Samanwokit (1953: 39) wrote about the timber King Taksin used in constructing warships at Chanthaburi, stating that large takhian trees were felled in the forest and sawn into strong and durable warboats, unmatched by any other wood. Because the King of Thonburi established a shipbuilding camp at Chanthaburi and used takhian wood to build the fleet that enabled the nation to regain its independence, he remembered the virtue of the takhian trees and sought to reconcile the people with them so that they would not destroy this wood but preserve it as a national blessing as much as possible. He therefore ordered influential figures to go around the provinces, and it was said that they encountered Nang Takhian, a guardian spirit of the takhian trees; whoever felled such trees would fall ill, as they were the dwelling places of forest deities and tree spirits. From then on the people did not dare cut takhian trees for any purpose. This belief has persisted in outlying provinces and has benefited the preservation of this valuable national timber without the need for laws or prohibitions. The benevolence of King Taksin the Great, as recounted here, is worthy of remembrance for all time.

1. The capture of Fort Vichai Prasit (Thonburi). In late October 1767 a fleet of one hundred vessels, each capable of carrying about one hundred soldiers (Sang Phatthanothai, n.d.: 159), loaded with provisions, military equipment and four thousand Thai–Chinese troops, departed from the mouth of the Chanthaburi River, entered the Gulf of Thailand and headed toward the mouth of the Chao Phraya River. When the fleet approached Fort Vichai Prasit, the landing plan for seizing the fort was executed exactly as intended. Once the fort had been taken, the force continued its advance by boat up the Chao Phraya River to the designated objective. In the initial stages of attacking and seizing various positions, Chao Tak employed amphibious landings at nearly every point. To clarify the situation, an excerpt from the book Thai at War with Burma is provided as follows:

Nai Thong In, also known as Bunsong (Praphat Trinarong, 2000: 3), whom the Burmese had placed in charge of guarding Thonburi, learned that Chao Tak’s fleet was entering through the river mouth, so he hurried to inform Suki, the Burmese commander at the Pho Sam Ton camp, and then called up men to defend Fort Vichai Prasit and the Thonburi ramparts in preparation for resistance. When Chao Tak’s forces arrived, the defenders, seeing that the approaching force was Thai, were unwilling to fight. After a brief clash, Chao Tak captured Thonburi and seized Nai Thong In, who was then executed.

2. The capture of the Pho Sam Ton camp. Chao Tak hastened his army toward Ayutthaya. Suki, the Burmese commander at the Pho Sam Ton camp, received the news sent by Nai Thong In, and shortly thereafter those who had fled from Thonburi arrived and reported that the city had fallen to the Thais. Startled by the news, Suki hurried to strengthen the defenses of the Pho Sam Ton camp. As it was the rainy season, he feared that the Thai forces might arrive before his preparations were complete, so he ordered Monya (or Monya), his deputy commander, to lead Mon and Thai troops who had previously submitted to Burma, forming a naval force to block the way at Paniad. Chao Tak reached Ayutthaya that evening and learned that an enemy force was stationed at Paniad. Not yet knowing its strength, he halted. Meanwhile, the Thai troops serving under Monya, realizing that a Thai army was advancing, became unsettled: some intended to flee, others wished to defect to Chao Tak. Seeing that the Thais under his command were unwilling to fight and fearing they might revolt, Monya fled back to the Pho Sam Ton camp that very evening.

At dawn Chao Tak learned from those who had fled the Burmese that the enemy had withdrawn completely from Paniad, so he pressed the advance. The Burmese encampment at Pho Sam Ton consisted of one camp on the eastern bank (near present-day Wat Hong, now abandoned) and one on the western bank (the main Pho Sam Ton camp). Suki, the Burmese commander, occupied the western side. This camp had been fortified with bricks taken from local temples, forming strong defensive walls and ramparts originally constructed when Ne Myo Thihapate commanded the siege of the capital, and it subsequently became Suki’s stronghold. Chao Tak pursued Monya to Pho Sam Ton and, upon arrival in the morning, ordered an assault on the Burmese camp on the eastern bank; by nine o’clock that camp had fallen. Chao Tak then secured the position and ordered ladders to be built for scaling the western fortifications. By evening he dispatched Phraya Phiphit and Phraya Phichai, Chinese officers, with their troops to take up positions close to Suki’s camp on the side of Wat Klang (likely Wat Kamphaeng, as it is much nearer, whereas Wat Klang is more than one kilometre distant). At dawn on Friday, the fifteenth day of the waxing moon of the twelfth month in the Year of the Pig, Chulasakarat 1129, corresponding to 6 November 1767 ( http://board.dserver.org/n/natshen/00000133.html 21/11/45), the Thai and Chinese forces launched a coordinated assault on Suki’s camp. Fighting continued from morning until midday, when Chao Tak’s forces broke into the Burmese camp. Suki, the Burmese commander, was killed in battle. Some of Monya’s men managed to escape, but many were captured, and many Thai soldiers formerly serving under Burmese authority willingly submitted.

The Royal Chronicles describe the assault on Pho Sam Ton as follows: When dawn broke on the waxing twelfth month, shortly after the third hour, the troops stormed the eastern side of the Pho Sam Ton camp and took it. His Majesty then ordered ladders to be made for scaling the large western camp where the Burmese commander was stationed. On the following day he ordered the Chinese vanguard to assault the commander’s camp. The commander led his men out to fight; they battled from morning until midday. The commander retreated into the camp, the Chinese troops pursued him inside, and he died fighting there. (image courtesy of Muang Boran)

Notes on the fate of Suki:

The Thai Royal Chronicles contain conflicting accounts regarding Suki’s end. The Royal Autograph Chronicle states that Suki fought to his death at the Pho Sam Ton camp, while Monya fled to join Krom Muen Thepphiphit. The British Museum version agrees with the Phanchanumat version and adds that when Krom Muen Thepphiphit captured Nakhon Ratchasima, he sent for the Burmese commander and Monya, who were then stationed in the capital, to come to Phimai.

The Phanchanumat Chronicle contains a passage stating that Krom Muen Thepphiphit sent men to summon Suki, the Burmese commander, and Monya, the deputy governor, to join his side, and that the commander therefore instructed Phraya Thibet Bori Rak, who held the office of Chao Phraya Si Thamathirat, to come out and present homage and submission, pledging service to Krom Muen Thepphiphit.

This version of the chronicle was revised by King Rama I in 1795, and may therefore be regarded as reliable.

Krom Muen Thepphiphit’s decision to align himself with the Burmese caused deep dismay among the Thai people. Thus the flight of Suki and Monya from the Pho Sam Ton camp to join him could not have remained hidden, and news of it reached Chao Tak. After Chao Tak marched against Chao Phraya Phitsanulok (Rueang) and was wounded in the shin by a gunshot, he was compelled to withdraw to Thonburi. Once his wound had healed and he learned that Suki and Monya had joined the major undertaking of Krom Muen Thepphiphit, he advanced to suppress them. Major battles were fought at Dan Khun Thot and Dan Choho, and Chao Tak’s forces achieved victory.

The Royal Autograph Chronicle states that Monya was captured, and it is presumed that Suki must also have been taken. When Chao Tak ordered Monya’s execution, it is understood that Suki likewise was put to death (Sang Phatthanothai, n.d.: 200–205).

When Chao Tak captured the Pho Sam Ton camp, he restored Ayutthaya to the Thai on 6 November 1767, meaning that King Taksin the Great recovered the capital within seven months, an extraordinary accomplishment.

After his victory over the Burmese, he encamped at Pho Sam Ton. At that time people and property that Suki had not yet sent to Burma were still stored inside the commander’s camp. Many officials the Burmese had seized were also held there, including Phraya Thibet Bodi (likely identical to Phraya Thibet Bori Rak), royal stewards and palace pages, who all came to pay homage to Chao Tak and informed him that King Ekkathat had died and that Suki had buried the royal remains at Khok Phra Meru (Paradee Mahakhan, 1983: 19; Chusiri Chamroman, 1984: 94). They also reported that several royal family members captured by the Burmese remained imprisoned in the camp, including four daughters of King Borommakot: Chao Fa Suriyat, Chao Fa Phinthawadi, Chao Fa Chanthawadi and Phra Ong Chao Fak Thong.

The grandchildren of the royal line held in the camp included Mom Chao Mit, daughter of Krom Phra Ratchawang Bowon Mahasenaphiwat (Chao Fa Kung); Mom Chao Krachad, daughter of Krom Muen Chit Sunthon; Mom Chao Mani, daughter of Krom Muen Sep Phakdi; and Mom Chao Chim, daughter of Chao Fa Chit—four princesses in all. These eight royal persons, having fallen seriously ill after their capture by the Burmese, had not yet been sent to Ava. When Chao Tak learned of their condition, he was moved with compassion. Earlier, when Chao Tak had taken Chanthaburi, he had encountered Phra Ong Chao Thapthim, a daughter of King Suea, who had been brought to Chanthaburi by attendants, likely because her mother was kin to the governor of Chanthaburi. Chao Tak had provided for her care, and he now arranged residences for these royal captives as appropriate. The Royal Autograph Chronicle of King Mongkut (pp. 603–604) records:

“…He commanded that no soldier should cause harm or distress to the people. When he saw the ancient royal lineage and ministers who were destitute and suffering, he bestowed garments on the commanders and officials of all ranks. He then had the royal remains carried on the Suriyamarin throne to Pho Sam Ton for cremation, and confirmed the ranks of the ministers to remain as before under the commanders. Furthermore, he sent officials to conciliate the people of Lopburi, and after this was accomplished, he summoned the distressed members of the ancient royal line to be cared for at Thonburi…”

Chao Tak ordered the release of all who had been imprisoned by the Burmese and distributed property, goods and provisions to relieve their suffering. He then had a white-draped cremation pavilion constructed on the Sanam Luang field, together with a decorated royal urn suitable for the royal funeral. Once all preparations were complete, Chao Tak entered the capital and set up a pavilion, ordered the royal remains of King Ekkathat to be exhumed and placed in the urn, and enshrined upon the newly built cremation pyre. Surviving monks were sought out and invited to perform the rites of merit transfer and chanting according to tradition. Chao Tak, together with members of the former royal family and the officials, then conducted the royal cremation and enshrined the relics in accordance with the custom observed for former kings (Sanan Silakorn, 1988: 64–69).

Note: Many people continue to misunderstand the location referred to as Pho Sam Ton. A publication by one institution, in discussing the abundance of food in Thonburi, mistakenly stated that the Burmese appointed Suki as commander to establish a camp at Pho Sam Ton in Thonburi to accumulate supplies and manpower. Such misunderstandings may continue to circulate and be cited repeatedly in later historical writings. To prevent confusion, including among visitors, both locations known as Pho Sam Ton are presented here.

Pho Sam Ton in Thonburi is the name of a lane branching from Itsaraphap Road. Within this lane is a market also called Pho Sam Ton, where a large bodhi tree still stands along with a local shrine. The lane and market are located in Wat Arun Subdistrict, Bangkok Yai District, Thonburi. The name Pho Sam Ton in Thonburi may be explained in several ways: in earlier times there may have been three bodhi trees, two of which later died while the name remained; or the name may have been adopted in honor of King Taksin’s decisive victory when he stormed the Pho Sam Ton camp at Ayutthaya, similar to the naming of Ban Phran Nok or Lat Ya Road (the latter recalling the Battle of Lat Ya during the Nine Armies War in Kanchanaburi).

Pho Sam Ton in Ayutthaya was the name of a Burmese military camp built during the siege of Ayutthaya in 1766 by the commander Ne Myo Thihapate. The three bodhi trees stood at Wat Pho Hom. Colonel Prayun Monthonphan, who had once been ordained there, stated that one of the trees died about sixty years ago; at present two remain in front of Wat Pho Hom. The Burmese camp, however, was established some 800 meters west of the temple and the trees, along the old Lopburi River. It was called ” the Pho Sam Ton camp ” because it lay within the Pho Sam Ton Subdistrict, not because the three bodhi trees stood inside or beside the camp. This camp was situated in Pho Sam Ton Subdistrict, Bang Pahan District, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya Province (Ruamsak Chaikomin, Lieutenant General, 1994: 27–32).