King Taksin the Great

Chapter 2: Ayutthaya and the Conditions of the Kingdom in Its Final Period before the Fall

2.1 What was the full name of the Kingdom of Ayutthaya?

The full name of the Kingdom of Ayutthaya was “Krung Thep Nakhon Bawon Thawarawadi Sri Ayutthaya Mahadilokphop Noppharat Ratchathani Burirum.”

The map was drawn by R.P. Placide, a geographer in the French diplomatic mission sent by King Louis XIV to Ayutthaya during the reign of King Narai in 1686 (2229 B.E.), near the end of King Narai’s reign. The map shows that the French embassy’s ship, commanded by Chevalier de Chaumont, sailed across the Indian Ocean and entered through the Sunda Strait—rather than the Strait of Malacca—passing between Sumatra and Java, through the Malay Peninsula into the Gulf of Siam, and arriving at the mouth of the Chao Phraya River. (Image from the book Ayutthaya)

2.2 How long had Ayutthaya been the capital city?

Ayutthaya had been the capital city for 417 years (from 1350 to 1767).

2.3 What were the characteristics of Ayutthaya?

There are accounts about Ayutthaya found in the Testimonies of the Inhabitants of the Old Capital and the Chronicles of Khun Luang Hawat (King Uthumphon). These were recorded after the Burmese took them captive during the second fall of Ayutthaya. The testimonies of the prisoners were written down in Burmese, and centuries later, a version translated into Mon was discovered and subsequently rendered back into Thai. The main content stated that

Ayutthaya was located at Nong Sono, in an area where several rivers converged, including the Chao Phraya, Lopburi, Pa Sak, and Noi rivers, which facilitated convenient transportation routes connecting to various cities within the kingdom. Originally, Ayutthaya was not an island. During the reign of King Maha Chakkraphat, a canal was ordered to be dug, branching from the Lopburi River near Hua Ro and joining the Bang Kacha or Chao Phraya River at the front of Pom Phet, turning Ayutthaya into an island surrounded by water to protect the city from enemy attacks. A major river flowed south from Ayutthaya into the Gulf of Thailand, allowing large foreign trade ships to sail directly to the city near Pom Phet conveniently. Consequently, Ayutthaya became an international port city of significance for trade exchanges between European and West Asian countries, such as the Netherlands, France, Iran, and India, and East Asian countries, including China, Vietnam, and Japan.

Map of Ayutthaya and its rivers

(Image from the book Ayutthaya)

The Kingdom of Ayutthaya (1351–1767 / 1893–2310 B.E.)

Map by Francois Valentin, 1726 (2269 B.E.)

(Image from the book Ayutthaya)

Ayutthaya had city walls that were originally made of earth. Later, during the reign of King Maha Chakkraphat, they were rebuilt with brick and mortar surrounding the capital, stretching 310 sen in length and about 4 wa in height. Along the walls were sema stones and bastions at intervals, including Pom Phet (located at the southern corner of the city near Bang Kacha to defend against enemies approaching by river from the south) and Pom Maha Chai (housing a cannon named Prab Hongsa, situated at the corner of Wang Chan Kasem near Hua Ro Market, now opposite Wat Sam Wihan, where the Burmese set up a camp to fire cannons before the second fall of the city).

Pom Sad Kob or Pom Tai Kob (located at the city corner along the Hua Laem River near Wat Phu Khao Thong, housing the Mahakan Mrityuraj cannon), Pom Supharat and Pom Pak Tho, and Pom Tai Sanom (situated north of Pom Sad Kob, also called Pom Nai Kai or Pom Nai Kan), Pom Hua Samut and Pom Pratu Khao Plaek (located north of Wat Thammikarat), Pom Maha Chai and Pom Wat Kwang (near the Front Palace, opposite Wat Mae Nang Pluem), Pom Ho Ratchakhrue (in front of Wat Suwannaram), Pom Champa Phon (an outer city bastion beyond Pratu Khao Plaek, north of Wat Tha Sai near Suan Luang Wat Sop Sawan), Pom Phet and Pom Tai Khu (along the river at Bang Kacha), Pom Wat Fang (between Wat Khok and Wat Tuek), and Pom Ok Kai (near Wat Khun Mueang Chai).

In Ayutthaya, there were elevated earthen roads, some paved with bricks, such as Patong Road (used for royal processions, passing in front of the City Pillar Shrine, now called Si Sanphet Road), Na Wang Road (passing in front of Phra Kan Shrine to Patom Maprao, 50 sen long, used for receiving foreign envoys), Na Bang Tra Road (from Tha Sib Bia to Patom Maprao), Chao Phrom Market Road (from the foot of Pa Than Bridge to Wat Chan), Lang Wang Road (beside the Drum Tower), Na Phra Kan Road (an intersection with Lang Wang Road at the city center called Talang Kaeng, near the area called Cheekun), and Patom Maprao Road (beside Wat Phlap Phla Chai), which corresponds with Ayutthaya (2003: 317), stating that most streets in the capital were compacted earthen roads built using elephants and human labor, often running parallel to canals, while some were paved with bricks. For example, the royal road called Maharathaya ran through the city center, paved with laterite, about 12 meters wide, connecting the old palace to Chai Gate in the south, and was used for state ceremonies such as royal processions, Kathin processions, royal funerals, and receiving diplomatic missions. The most modern and bustling street was Mour Road, paved with herringbone bricks using advanced technology, allowing carriages and carts to travel smoothly. Important districts along Mour Road included the residences of Okya Wicha Yent, the office receiving envoys, Brahmin quarters, Muslim quarters, and Chinese quarters, all serving as commercial hubs with several intersecting streets. Other streets in the capital were named according to their trade zones, such as Takuapa Road, Pa Krieb Road (pan selling area), Ban Khan Ngern Road, Pa Ya Road (spices and Thai products), Pa Chomphu Road (textiles), Pa Mai Road, Pa Lek Road, Pa Fuk Road (bedding and pillows), Pa Pha Kiao Road (clothing), Ban Chang Tha Ngern Road, Cheekun District Road (fireworks and liquor), Ban Kra Chi Road (Buddha image production), Kanom Jeen District Road (selling Chinese buns and sweets), Nai Kai District Road (goods from China), Pa Din So Road, Ban Hae Road (fishing nets and fish traps), and Ban Brahmin District Road (baskets and containers). If roads were damaged, broken bricks were removed, or new layers were added during floods. Archaeological excavations show some streets were repaired three to four times. Some present-day streets within the island city were built over ancient routes, such as U Thong Road, which overlies the city walls and parts of the fortifications, 12.4 kilometers long. Rojana Road served as a main thoroughfare connecting the city to external areas. There were numerous bridges, both wooden and brick; late Ayutthaya records indicate a total of 30 bridges, 15 brick and 15 wooden, such as Pa Than Bridge, Cheekun Bridge, Chinese Gate Bridge, Thep Mee Gate Bridge, Chang Bridge, and Sai Soi Bridge (Ayutthaya, 2003: 318).

…There were many canals in Ayutthaya, with water gates made of Takian or Teng Rang wood posts, driven into the canal mouths in two layers and filled with earth in the center to prevent flooding during the rainy season and to store water for use in the capital during the dry season. Examples include Khlong Chakrai Yai (located at the rear of the palace, flowing into the Phutthaisawan River), Khlong Pratu Khao Plaek connecting to Khlong Pratu Chin (in Tha Sai Subdistrict, flowing south into the river), Khlong Ho Rattanachai, Khlong Nai Kai (south of Wang Chan Kasem, eastward to the river near Pom Phet), Khlong Pratu Chin (south, above Khlong Nai Kai), Khlong Pratu Thep Mee or Khao Sami (near Khlong Pratu Chin), Khlong Chakrai Noi (north of Khlong Pratu Thep Mee), and Khlong Pratu Tha Phra. There was also a large pond in the city called Bueng Chi Khan (Bueng Phra Ram), which served as a water source during the dry season when river levels dropped significantly.

There were several water gates for controlling the flow of water, including Pratu Khao Plaek, Pratu Ho Rattanachai, Pratu Sam Ma, Pratu Chin, Pratu Thep Mee, Pratu Chakrai Noi, Pratu Chakrai Yai, and Pratu Mu Thaluang. The city gates were about six sok wide, with multiple earth-red stupas on top (as seen from the walls of the ubosot at Wat Yom and from ancient records), serving as land gates.

For example, Pratu Si Chai Sak, Pratu Chakramahima, Pratu Maha Paichayon, Pratu Mongkhon Sunthon, Pratu Somnaphisan, Pratu Thawar Chedsa, Pratu Kalyaphirom, Pratu Udom Khongkha, Pratu Maha Phokharat, Pratu Chatinava, Pratu Thakkinaphirom, Pratu Phrom Sukhot, Pratu Thawar Wichit, Pratu Olarik Chat, Pratu Thawar Nukul, Pratu Niwet Wimon, Pratu Thawar Uthok, Pratu Phra Phikhnesuan, Pratu Si Sanp Tawad, Pratu Nakhon Chai, Pratu Phon Tawad, Pratu Sa Daeng Ram, Pratu Sa Do Kra, Pratu Tha Phra, Pratu Chao Prap, Pratu Chai, Pratu Chao Chan, Pratu Chong Kut, and others. All of these city gates have been completely destroyed in the present day.

The painting Afbeldine der Stadt Judiad shows the foundational shape of Ayutthaya as an “island in the river,” depicting the city layout with roads and canals interconnected as transportation routes. (Image from the book Ayutthaya)

Royal ceremonial barges of the Ayutthaya Kingdom

From a Western painting (Image from the book Ayutthaya)

There was a royal ceremonial shipyard located in Khu Mai Rong Subdistrict, between Wat Choeng Tha and Wat Phanom Yong, housing more than 150 vessels. The royal barge hall, 1 sen 5 wa long, stretched along Wat Teen Tha to Khu Mai Rong (today, local villagers have frequently discovered ancient ship fragments in this area). There were large sea-going vessels used for royal fishing of giant catfish and sharks, including two royal barges called Phra Krut Pha and Phra Hong Pha. In addition, there were major royal barges named Kaew Chakramani and Suwan Chakrarat, as well as secondary royal barges named Suwan Piman Chai, Sommut Piman Chai, and Salika Long Lom. The crews numbered 500 rowers, residing in Ban Pho Riang and Ban Phut Lao.

The Maha Chakkarat Cannon was cast in bronze and features a pair of lifting handles. At the rear of the barrel are floral and leaf designs, along with a crown motif on the ornamental pattern, and the fuse has a decorative kanok design. It was manufactured at the Douai foundry in France by J. Béranger on 12 September 1768 (2311 B.E.). It is currently displayed in front of the Ministry of Defence.

(Image from http://www1.mod.go.th/opsd/sdweb/cannon3.htm)

The major cannons in Ayutthaya included Narai Sanghanar (used in 1653, before the first fall of Ayutthaya), Maha Rerk, Maha Chai, Maha Chakkra, Maha Kan, Prab Hongsa (used in 1767), Chawa Taek, Angwa Laek, La Waek Phinas, Phikhart Sanghanar, Mar Palai, Mahakan, Maha Mrityuraj (used in 1767), and Ta Pakhao Kwad Wat.

A layout showing the locations of the various royal halls in the Grand Palace, which were first established during the reign of King Borommatrailokkanat, as Ayutthaya had grown into a kingdom and needed a reorganized system suitable for its development.

(Image from the book Phra Thinang Sanphet Prasat)

In the royal palace of Ayutthaya, there were several throne halls used by the king, built during the reign of King U Thong (1350–1369). These included Phra Thinang Phithun Mahaprasat, Phra Thinang Paichayon Mahaprasat, and Phra Thinang Aisawan Mahaprasat, which are believed to have been constructed of wood. Later, a fire occurred, and King Borommatrailokkanat converted the former royal palace grounds into a Buddhist monastery in 1452 (currently the area of Wat Phra Si Sanphet, which has three large stupas beside the Viharn Phra Mongkhon Bophit containing the royal ashes of King Borommatrailokkanat, King Borommaracha III, and King Ramathibodi II).

Phra Thinang Sanphet Prasat (replica), Muang Boran, Samut Prakan Province

(Image courtesy of Muang Boran)

Phra Thinang Sanphet Prasat was an important and the oldest royal hall, used for state affairs and major royal ceremonies of the kingdom. It was completely burned by the Burmese, leaving only the foundation, during the second fall of Ayutthaya in 1767 (2310 B.E.).

(Image from the book Phra Thinang Sanphet Prasat)

The foundation ruins of Phra Thinang Sanphet Prasat in Ayutthaya show narrow stepped platforms, designed to allow people to crawl up to the main hall in accordance with ancient royal tradition.

(Image from the book Phra Thinang Sanphet Prasat)

Phra Thinang Sanphet Mahaprasat (replica) features long front and rear pavilions, short side pavilions, and a curved roof parallel to the base. The roof finials are modeled after carved wooden designs from Sanket, similar to those on the Viharn of Phra Buddha Chinnarat, Phitsanulok.

(Image courtesy of Muang Boran)

Inside the royal hall, the front and rear each have three doors. The side doors are small, while the central door is large, featuring a stupa-shaped finial. The base forms a tiered platform decorated with motifs of Thepphanom, Garuda, and lions.

The original central hall of Phra Thinang Sanphet Prasat featured mural paintings depicting the ten incarnations of Vishnu, as recorded in the Hor Wang manuscripts from the Ayutthaya period. It also housed a three-tiered royal throne covered in gold and adorned with nine precious gems, which the Burmese later took to Ava during the fall of Ayutthaya in 1767 (2310 B.E.). This hall was significant for royal coronations and for receiving important foreign envoys during the reign of King Narai the Great, such as the envoy Chevalier de Chaumont bringing a letter from King Louis XIV of France, and Laloubère on his second mission. Later, King Buddha Yodfa Chulaloke commissioned a replica to construct Phra Thinang Inthraphisek, but it was destroyed by fire, leading to the construction of Phra Thinang Dusit Mahaprasat instead (Touring Muang Boran: For Students, 2003: 18–19). (Image courtesy of Muang Boran)

The upper walls surrounding the royal hall feature the Bum Khao Bind Kan Yaeng pattern and stupa-shaped motifs gilded and inlaid with white glass. The lower section displays guardian figures within square frames, also gilded and inlaid with white glass. The windows are decorated with mother-of-pearl designs, modeled after the door panels of the Viharn Yod at Wat Phra Si Rattana Satsadaram.

(Image courtesy of Muang Boran)

The star-patterned ceiling is gilded and inlaid with glass, modeled after the ceiling of the prang at Wat Phra Si Rattana Mahathat in Si Liong.

(Image courtesy of Muang Boran)

During the reign of King Borommatrailokkanat (1452–1490), new palaces were constructed north of the old royal palace, including Phra Thinang Sanphet Mahaprasat and Phra Thinang Bencharat Mahaprasat. In the reign of King Prasat Thong, Phra Thinang Si Riyasothorn Mahapiman Banyong was built, later renamed Chakrawat Paichayon Mahaprasat. Other halls included Phra Thinang Suriyas Amarin, Phra Thinang Yannang Rattanat, and Phra Thinang Piman Ratchaya. (Today, some Ayutthaya-era halls are replicated at Muang Boran, Bang Pu, as the originals were destroyed, leaving only foundations or nothing at all.) There was a three-tiered drum tower, 10 wa high at Talang Kaeng. The top tier, named Maha Rerk, was used to watch for enemies; the middle tier, Maha Rangap Dab Ploy, observed fires and signaled: three drumbeats if fires occurred outside the city, continuous drumming if fires broke out along or inside the city walls. The lowest tier held a large drum called Phra Thiwaratri, struck at noon, during royal assemblies, sunrise, and sunset. The drum tower was guarded by the Department of the Capital, which kept cats to prevent rats from damaging the drums. Each morning and evening, five biae (coins) were collected from market shops in front of the prison to buy grilled fish for the cats.

During the reign of King Narai the Great, when Lalubere arrived as an envoy, he estimated that the population of Ayutthaya was about 150,000 people. Houses were built of wood along canals, rivers, and near the city walls. The central area of the city was mostly open space with few residences. There were only a few masonry buildings in Siam, such as the European trading houses near the barge dock at Talat Khu, the Korasan building of the Persians in Lopburi (sometimes called Tuk Khotchan), and Portuguese, Dutch, and Japanese houses along the river in Pak Nam Mae Bia Subdistrict, south of Pom Phet. The French constructed a church and residences at the mouth of Khlong Takhian to the north.

There were many Buddhist temples, such as Wat Phanan Choeng, located at the tip of Bang Kacha near the seagoing boat dock at the mouth of the Mae Bia River. The Royal Chronicles of the Old Capital, compiled by Luang Prasert Aksorn Niti, recorded that “…Chulasakarat 696, year of Chuat, first established Phra Buddha at Phanan Choeng,” indicating that the principal Buddha image at Wat Phanan Choeng was created in 1424, 26 years before Ayutthaya was founded as the capital. Wat Mae Nang Pluem was an ancient temple from the Ayutthaya period, situated near Wat Na Phra Meru, where the Burmese placed cannons to attack Ayutthaya before the second fall. Wat Khok Phaya or Khok Phra Ya, located behind Wat Na Phra Meru outside the city near Phu Khao Thong, served as the execution site for high-ranking nobles using the moon log method. Wat Sala Poon contained significant late Ayutthaya period mural paintings.

Large stern-swinging boats from Phitsanulok carried sugarcane juice and tobacco to sell in front of Wat Kluai. Large stern-swinging boats from Sukhothai brought northern products to dock along the river and at Khlong Wat Mahathat. The Mon people transported mature coconuts, Siamese rosewood, and salt to sell at the mouth of Khlong Ko Kaew. Carts from Nakhon Ratchasima carried lacquer, beeswax, bird wings, tarang cloth, baihua cloth, leather, tendons, and meat sheets to sell at Sala Kwan.

Villagers from Wiset Chai Chan transported unhusked rice by boat to sell at Ban Wat Samo, Wat Khun, and Wat Khanan. Local residents there operated mortars and pestle rice mills to process rice for sale to junks and ran distilleries. Chinese brewed liquor for sale at Ban Pak Khao San. Raaeng boats from Tak and hawk-tail boats from Phetchabun, owned by Mr. B, carried lacquer, incense, shrimp-tail iron, rattan, camphor, rubber oil, tobacco, and various goods along the districts to dock and sell. At Ban Lang Tuk, Phutthaisawan, sesame oil was extracted for sale. Outside the Chai Khrai wall, villagers sold pole rafters and bamboo rafts. Villagers from Yi San, Ban Laem, and Bang Thalu of Phetchaburi transported shrimp paste, fish sauce, salted crabs, snapper, mullet, mackerel, and grilled stingrays to dock and sell. At Ban Poon, Wat Khian, lime was produced and sold. At Ban Phra Kran, villagers caught gourami to sell in the capital for releasing during the Songkran festival. In front of Wat Ratchaplee and Wat Tharma, coffins and funeral items were sold. In the Patong area, cotton was sold. Talang Kaeng market, selling fresh goods morning and evening, was located in front of the prison. Talang Kaeng was also the site for executions by beheading, and bodies were cut into pieces and displayed on Pa Thon Road near the drum tower and Wat Phra Ram. Another execution site was at Tha Chang Gate, along the Lopburi River on the northern side of the city near Wat Khongkharam. At both execution sites, the public could observe the executions.

During the monsoon season, Chinese junks and Suratte ships from India, England, France, and European merchants anchored at Ban Tai Khu, unloading goods onto warehouses inside the city walls. Malay Cham ships carried betel nuts to sell at Khlong Khu Cham. (In later times, several sunken junks were found underwater, some showing signs of burning; divers retrieved antiques for sale.) Chinese distillers raised pigs at Ban Khlong Suan Phlu and operated liquor factories on the river at Hua Laem, south of Wat Phu Khao Thong under the Nang Hin Loi shrine. Cham merchants sold small and large Lantai mats at Ban Tai Khu, wove silk and cotton at Wat Lot Chong, and spun coconut husk ropes to sell to Suratte ship captains from England at Ban Tha Kayi. (Source: Department of Fine Arts: Accounts of the Old Capital by Phraya Boran Ratchathanin, published for the royal cremation of Miss Phen Dechakup, December 12, 1998, and Somdet Phra Chao Boromwong Thoe Krom Phraya Damrong Rachanuphap: Testimonies of the Old Capital People, Khlang Wittaya Publishing, 1972, cited in Arthorn Chantawimon, King Boromkosa (AD 1732-1758), in History of Thailand: From the Dinosaur Era, Ban Chiang, Ayutthaya, Maythamlin to 2003, 2003: 223–227).

2.4 How many kings ruled Ayutthaya, which royal dynasties did they belong to, and what was the last royal dynasty?

During the period when Ayutthaya was the capital, there were a total of five royal dynasties:

1) the Chiang Rai Dynasty

2) the Suphanburi Dynasty

3) the Sukhothai Dynasty

4) the Prasat Thong Dynasty, and

5) the Ban Phlu Luang Dynasty

The last royal dynasty was the Ban Phlu Luang Dynasty. Ayutthaya had a total of 33 monarchs (or 34 if Khun Worawongsa Thirath is included), as follows:

1. Chiang Rai Dynasty (or Wiang Chai Prakan Dynasty)

King Uthong (image from the Rattanakosin Sculpture Album)

- King Ramathibodi I (King Uthong) reigned from 1351–1371 (20 years)

- King Ramesuan (son of King Ramathibodi I) reigned twice:

– in 1371 (1 year), he abdicated in favor of Khun Luang Phong and went to live in Lopburi

– from 1388–1395 (7 years)

2. Suphanburi Dynasty (or Wiang Chai Narai Dynasty)

3) King Borommarachathirat I (Khun Luang Phon) from the Wiang Chai Prakan Dynasty, maternal uncle of King Ramesuan, came from Suphanburi, seemingly to claim the throne. King Ramesuan therefore willingly ceded the throne to him. Reigned 1913–1931 BE.

4) King Thong Lan (or King Thong Chan), son of Khun Luang Phon, reigned only 7 days before King Ramesuan returned from Lopburi, entered the palace, and had Thong Lan executed.

5) King Ramrachathirat (son of King Ramesuan) reigned 1938–1952 BE (14 years). Chao Khun Luang Maha Senabodi, the Samuhanayok, rebelled, captured Ayutthaya, and gave the throne to King Intharacha (Wiang Chai Narai Dynasty).

6) King Intharacha, also called King Phra Nakhon In or King Nakhon Intharachathirat (grandson of King Borommarachathirat I), reigned 1952–1967 BE (14 years). King Intharacha had three sons: Chao Ai Phaya, Chao Yi Phaya, and Chao Sam Phaya, who were appointed governors of Suphanburi, Phraek Si Racha, and Chai Nat, respectively.

After the death of King Intharacha, Chao Ai Phaya and Chao Yi Phaya raised armies to contest the throne. During the battle, both brothers were killed in elephant combat, their necks severed simultaneously. The ministers then invited Chao Sam Phaya to ascend the throne as King Borommarachathirat II (Chao Sam Phaya, son of King Intharacha), who reigned 1967–1991 BE (24 years).

The elephant duel between Chao Ai Phaya and Chao Yi Phaya to contest the throne (Image from Ayutthaya).

King Borommarachathirat III

8) King Borommatrailokkanat (son of King Borommaratchathirat II) reigned 1548–1588 BE (39 years)

9) King Borommaratchathirat III reigned 1588–1591 BE (4 years)

10) King Ramathibodi II (younger brother, son of King Borommatrailokkanat) reigned 1591–1629 BE (38 years)

11) King Borommaracha IV (also called Borommaracha Mahaphutthangkun or Noi Phutthangkun) reigned 1629–1633 BE (5 years)

12) King Ratsadathirat Kuman reigned 1633 BE (5 months); his uncle came with an army from Phitsanulok, executed him, and took the throne as King Chai Raja Thiraj

13) King Chai Raja Thiraj (son of King Ramathibodi II) reigned 1634–1646 BE (12 years)

14) King Kaewfa, or King Yodfa (son of King Chai Raja Thiraj at age 11, mother Queen Si Sudachan) reigned 1646–1648 BE (2 years), with Queen Si Sudachan serving as regent. She later elevated Khun Worawongsathirat (or Khun Chinarat) to the throne, but his reign was short and is not officially counted. Khun Phiren Thep (of the Wiang Chai Buri dynasty) and nobles captured and killed Khun Worawongsathirat and Queen Si Sudachan, then gave the throne to Prince Thianracha, a royal relative of King Chai Raja Thiraj.

15) King Maha Chakkraphat, or King White Elephant (Prince Thianracha, younger half-brother of King Chai Raja Thiraj) reigned 1648–1663 BE (15 years)

16) King Mahinthrathirat (son of King Maha Chakkraphat) reigned 1663–1669 BE jointly with his father. During this time, the Burmese under King Bayinnaung invaded. Internal divisions and betrayals among Thai officials occurred, ultimately leading to the capture of King Mahinthrathirat by the Burmese, though he died en route to Hanthawaddy.

3. Sukhothai Dynasty (Wiang Chai Buri Dynasty)

17) Somdet Phra Maha Thammarachathirat (or Somdet Phra Sanphet I) reigned 1569–1590 BE (22 years). At that time, Ayutthaya was a vassal state under Burma.

18) Somdet Phra Naresuan Maharat (or Somdet Phra Sanphet II), son of Somdet Phra Maha Thammarachathirat, reigned 1590–1605 BE (15 years). During his reign, Somdet Phra Naresuan declared independence from Burma in 1592 BE.

19) Somdet Phra Ekathotsarot (or Somdet Phra Sanphet III), younger brother of Somdet Phra Naresuan Maharat, reigned 1605–1620 BE (15 years).

20) Somdet Chao Fa Si Saowaphak (or Somdet Phra Sanphet IV), son of Somdet Phra Ekathotsarot, reigned 1620 BE (less than 1 year). Phra Si Sin of the royal family, a rebel, captured and executed him, then ascended the throne.

21) Somdet Phra Chao Songtham (or Somdet Phra Borommaraja I), maternal uncle of Somdet Chao Fa Si Saowaphak, reigned 1620–1628 BE (8 years).

The Monument of King Naresuan the Great

22) Somdet Phra Chetthathirat (or Somdet Phra Borommaraja II), son of Somdet Phra Chao Songtham, reigned 1628–1630 BE (2 years). Chao Phraya Kalahom seized power, executed Somdet Phra Borommaraja II, and bestowed the throne on Somdet Phra Athittayawong, younger brother of Somdet Phra Borommaraja II.

23) Somdet Phra Athittayawong, 1630 BE, aged 9, reigned about 7 months (some sources say 36 days). The council of ministers decided it was appropriate to transfer the throne to Chao Phraya Kalahom Suriyawong.

4. Prasat Thong Dynasty

King Narai the Great

(Image from the Rattanakosin Kingdom Sculpture Album)

24) King Prasat Thong, or King Sanphet V (originally Chao Phraya Kalahom Suriyawong), reigned 1629–1655 BE (26 years)

25) Crown Prince Chai, or King Sanphet VI, reigned 1655–1656 BE (1 year) (He was the son of King Prasat Thong and Phra Sri Suthammaracha. He rebelled, was captured, and executed.)

26) King Si Suthammaracha, or King Sanphet VII, reigned 1656 BE (3 months). Crown Prince Narai’s faction rebelled, captured, and executed him, then seized the throne.

27) King Narai the Great, or King Ramathibodi III (son of King Prasat Thong), reigned 1656–1688 BE (32 years). He suppressed rebellions led by Ok Phra Phet and Ok Luang Sorasak, executing royal family members involved. After King Narai’s death, Ok Phra Phet (Phetracha) ascended the throne.

5. Ban Phlu Luang Dynasty

28) King Phetracha or Somdet Phra Maha Burut (from Ban Phlu Luang, Suphanburi) reigned 1688–1703 (15 years)

29) Somdet Phra Si Sanphet VIII (commonly called King Suea) (originally Khun Luang Sorasak, son of King Phetracha) reigned 1703–1710 (7 years)

30) King Tai Sa or Somdet Phra Si Sanphet IX or King Phumintharacha (son of King Suea) reigned 1710–1734 (23 years)

31) King Borommakot (or Boromkos) or Somdet Phra Boromrajadhiraj III (Prince Phon, younger brother of King Tai Sa) reigned 1734–1760 (26 years)

32) King Uthumphon or Somdet Phra Boromrajadhiraj IV (Prince Dok Ma Duea, Krom Khun Phonphinit, son of King Borommakot, commonly called Khun Luang Ha Wat) reigned 1738 for about 2–3 months and then abdicated in favor of his elder brother.

33) King Ekathotsarot or Somdet Phra Thatana Suriya Marint or Somdet Phra Boromrajadhiraj III (Krom Khun Anurak Montri, commonly called Khun Luang Khi Ruan, elder brother of Prince Dok Ma Duea) reigned 2301–2310 BE (1758–1767 CE); during his reign the kingdom deteriorated, and the Burmese invaded Ayutthaya in 2310 BE (1767 CE).

(Source: Royal Chronicles of Ayutthaya, Luang Saraprasert edition and Krom Phra Borommanuchit edition, vol. 1, 1961: Table of Contents; Political History of the Thai People – Three Revolutions by Prakob Choprakan, Somboon Khon Chalad, and Prayut Sitthiphun, n.p.: 45–47; Historical Annals, vol. 18, no. 1, 1984: 43–45; and Thuan Boonyaniyom, 1970: 163–167)

2.5 What are the royal biographies of the last three kings from the Ban Phlu Luang dynasty?

1. King Borommakot (r. 2275–2301 BE) was the 31st monarch of Ayutthaya. In 2275 BE, upon the death of King Tai Sa, a succession struggle occurred among his sons, Prince Aphai and Prince Poramet, who fought against the Maha Uparat (Deputy King), Prince Phon or Phra Bandhun Noi, a younger brother of King Tai Sa and son of King Suea. The Maha Uparat emerged victorious, executing his rivals and ascending the throne as King Boromkhoja (sometimes called King Boromkhot). During his reign, officials loyal to Princes Aphai and Poramet were purged, weakening Ayutthaya’s military strength. He promoted trade, scholarship, and culture, commissioning literary works such as Inao, Kaph Hoe Ruea, Punno Watkham Chan, Kalawat Sirivibulkit, and Khlong Chalo Phra Phutthasaiyas.

King Boromkot

In 2276 BE, nine Chinese junks arrived in Siam, and a Siamese envoy was sent to China. In November 2279 BE, the Siamese forces, armed with weapons, laid siege to the Dutch settlement in Ayutthaya due to a dispute over the pricing of textiles imported from India.

In 1747, King Borommakot made a royal pilgrimage to pay homage to the Buddha’s Footprint in Saraburi. His Majesty traveled by water along the Pa Sak River to Ban Tha Ruea, and then continued by land to Wat Phra Phutthabat. On this journey, Jacobus van der Heuvel, a Dutch merchant, accompanied the royal procession and recorded that he visited Prathun Cave and Than Thong Daeng Stream, as well as attended a theatrical performance. During this period, members of the Bunnag family, who were of Muslim descent, converted to Buddhism. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) purchased deerskins, stingray skins, and sappanwood from Siam to sell in Nagasaki, Japan, and exported tin, lead, and ivory to Batavia.

In 1749, a smallpox epidemic broke out, causing a great number of deaths.

The image shows stingray leather products of various sizes from Siam, which the Dutch brought to Japan in 1747 (B.E. 2290) during the reign of King Borommakot, to be used for making samurai sword handles. (Image from the book The History of the Thai Land: From the Hundred-Million-Year Dinosaur Era, the Ban Chiang Stone Age, Ayutthaya, Black May, to B.E. 2546)

Note

Smallpox, or variola, is a disease caused by the Variola virus. It was last recorded in Thailand in 1961 (B.E. 2504). The disease spreads through the air via droplets from an infected person’s secretions, such as mucus or saliva, or through direct contact with skin lesions. The virus is highly resistant to various weather conditions, whether hot or cold, and can be easily transmitted from person to person. Patients typically experience high fever, body aches, headache, back pain, and abdominal pain. In some cases, neurological symptoms such as delirium, aggression, or stupor may occur. Subsequently, sores develop in the mouth, throat, face, trunk, arms, and legs. The skin lesions appear as pustules that initially look clear but soon become opaque with pus.

Condition of a child infected with smallpox (Variola)

The disease resembles chickenpox but is far more severe within 24–48 hours. The pustules take about 8–9 days to dry and form black scabs, eventually leaving scars after 3–4 weeks. It is contagious from the onset of symptoms, with the first week being the period of highest transmissibility, and remains so until the scabs have completely dried. In recent times, there have been attempts to use this virus as a biological weapon, as it affects the respiratory system—similar to anthrax and plague. (http://www.manager.co.th/Home/ViewNews.aspx?NewsID=4632818276285, July 14, 2004)

In 1751, Burma lost the city of Ava to the Mon.

On July 17, 1751, the Sri Lankan envoy arrived in Ayutthaya and described: “…within the city walls, there are many canals running parallel, with numerous boats and people traveling by water beyond description…shops selling various goods, including golden Buddha images, were also present.” The Sri Lankan diplomat who visited Siam recorded: “On Wednesday, the ninth day of the waxing moon, seventh month, a pilot guided the ship into the river mouth, docking at the area called Amsterdam, which the Dutch (present-day Netherlands) had established at the river mouth.” During the second Thai envoy to Sri Lanka in 1752, it was recorded: “On Monday, the fifteenth day of the waxing moon, second month, the ship departed from Thonburi to the Dutch building at Bang Plakod.”

Map of the Chao Phraya River during the reign of King Thai Sa, by Francois Valentijn (Amsterdam, 1726 B.E. 2269) (Image from the book Ayutthaya).

In 1753 (B.E. 2296), the Dutch East India Company arranged a ship to send 19 Thai monks to be ordained in Ceylon, as King Kirti Sri Rajasinha of Kandy had requested Siamese monks to help revive the declining Buddhism there. Consequently, Phra Ubali, Phra Ariyamani, and fifty other monks traveled to Ceylon, bringing with them Buddha images, including Phra Phuttha Patimakorn Ham Samut, and the Tipitaka (the aforementioned Tipitaka has been well preserved in Ceylon to this day). The Siamese monks stayed at Wat Buppharam in Kandy and conducted ordinations, continuing the Siamese monastic lineage.

Map of Ceylon, present-day Sri Lanka

(Image from http://www-user.tu-chemnitz.de/. ../srilan-map.jpg)

Wat Kudee Dao (Image from http://www.pantip.com/cafe/gallery/topic/G2875425/G2875425.html)

An image believed to depict Prince Uthumphon, who was captured by the Burmese after the war of 1767 (B.E. 2310) (Image from the book Ayutthaya).

In the same year, Alaungpaya, who had formerly been a Burmese hunter named Mang Aung Zeya, captured the cities of Ava and Pegu and ascended the throne as King of Burma during the late reign of King Borommakot.

King Borommakot had a son, Prince Uthumphon, titled Krom Muen Phonphinit, or Khun Luang Ha Wat, who served as the Grand Viceroy and held the title of Prince Ekathat. It is said that Prince Ekathat was blind in one eye.

During this reign, Wat Kudee Dao, an ancient temple established before the founding of Ayutthaya, was renovated (Athon Chantrawimon, 2003: 220–222).

Note

Wat Kudee Dao is an abandoned temple located along a road in the Wat Kudee Dao alley, near Wat Mahathong to the east. There is no clear documentary evidence regarding its original construction. The only record in the Royal Chronicles of Ayutthaya notes that it underwent major restoration during the reign of King Borommakot, while he held the title of Grand Viceroy, in 1711 B.E.

After excavation, it was found that the ancient structures within Wat Kudee Dao were originally constructed during the early Ayutthaya period. Evidence shows layers added over the principal chedi and the ubosot built atop the foundations of earlier buildings from the same period, likely corresponding to the major restoration carried out by King Borommakot, along with the construction of the vihara and additional chedis within the temple. To the north, outside the temple walls, a two-story building commonly called the “Phra Tamnak Kamalian” is visible, with a design similar to the Mahathong and Wat Chao Ya residences. It is believed to have served as the residence of King Borommakot while he oversaw the temple’s restoration. (http://www.thai-worldheritage.com/thai/ayuth-monu-out-E.html, July 15, 2004)

2. King Uthumphon was the 32nd monarch of Ayutthaya. He was a royal…

He was the son of King Borommakot and Queen Phanwasanoi (Krom Luang Phiphit Montri, later elevated to Krom Phra Thepamat). When King Borommakot punished the Grand Viceroy, Prince Thammathibet, for having an affair with the king’s consort, Princess Sangwan, leading to his death, both Krom Muen Thepphiphit, the minister, petitioned King Borommakot to appoint Prince Uthumphon (also known as Prince Dok Maduea), who at that time held the title Krom Khun Phonphinit, as the new Grand Viceroy in place of Prince Thammathibet.

According to foreign chronicles, Prince Uthumphon was intelligent and quick-witted, having learned the scriptures at the monastery from a young age, with a deep devotion to Buddhism and a modest disposition. Prince Uthumphon, holding the title Krom Khun Phonphinit, observed that the royal family was not harmonious and feared future troubles. He therefore petitioned King Borommakot, claiming that Krom Khun Anurak Montri, his elder brother, was still alive, and requested that he be appointed Grand Viceroy. This angered the king, as it went against his wishes. The king remarked that Krom Khun Anurak Montri was foolish, lacking wisdom and diligence, and that if he were given the throne, the kingdom would fall into disaster. Not seeking personal gain, the king ordered Krom Khun Anurak Montri to enter the monkhood so as not to obstruct state affairs. Fearing royal punishment, he complied. Prince Uthumphon, Krom Khun Phonphinit, did not dare to oppose this command. Consequently, King Borommakot appointed him as Grand Viceroy in the Year of the Ox, 1758 (B.E. 2301). In the same year, King Borommakot fell seriously ill and passed away, after which Prince Uthumphon, Krom Khun Phonphinit, ascended the throne.

Prince Ekathat, Krom Khun Anurak Montri, the elder brother, left the monkhood, but while King Borommakot was still seriously ill, he assumed authority independently, seating himself on the Phra Thinang Suriya Amarin (or Phra Thinang Suriya Marin) throne as if he were king. Observing that his elder brother intended to seize the throne, King Uthumphon, who had no ambition for power, reigned for just over three months before voluntarily surrendering the kingship to Prince Ekathat. He then entered the monkhood at Wat Atsanan Vihara (or Atsanavas Vihara), a royal temple formerly known as Wat Pradu Rong Tham, located outside the eastern moat of the capital. Upon ordination, the populace bestowed upon him the title Khun Luang Ha Wat. (Tuan Boonyaniti, 1970: 27–28)

Note

After King Uthumphon (Krom Khun Phonphinit or Khun Luang Ha Wat) abdicated in favor of King Ekathat, he occasionally entered the monkhood but would reside at Phra Tamnak Kham Yat, a palace he had constructed within the grounds of Wat Pho Thong, Kham Yat Subdistrict, Pho Thong District, Ang Thong Province. Because King Ekathat expressed disdain, Uthumphon withdrew to live away from the capital. When the Burmese approached the capital, he left the monkhood to help command the defense. After the conflict, he returned to monkhood, residing for a period before finally settling at Wat Pradu Songtham, outside the city walls.

Phra Tamnak Kham Yat (reconstruction) at Ancient City, Samut Prakan Province

(Image courtesy of Ancient City)

Phra Tamnak Kham Yat, Ang Thong

(Image from Encyclopedia of Central Thai Culture, Vol. 3)

Phra Tamnak Kham Yat is believed to have originally been located within the grounds of Wat Pho Thong, which at the time was still active, but later fell into ruin during the sacking of the capital. The palace was built of brick and stucco, raised above the ground, rectangular in shape, measuring approximately 10 meters wide and 20 meters long, with a ground floor and arched openings forming small chambers. The windows inside the building were pointed-arch style, and the interior was spacious with wooden plank flooring. The foundation of the palace curved like a ship’s hull, containing five rooms, with front and rear projections and a shrine room. The upper structure had collapsed. It is believed to date from the 18th century, following construction styles that had been prevalent since the reign of King Narai the Great. The palace featured a bulbous front projection facing east, with only the walls remaining of the compact building. (Ancient City Travel Guide: For Students, 2003: 20)

3. King Ekathat (or Phra Thinang Suriya Marinthra)

He was the son of King Borommakot, born to Queen Phanwasanoi, and later elevated to the title Krom Khun Anurak Montri. He was the elder brother of King Uthumphon, who abdicated after reigning for just over three months. Prince Ekathat was crowned king at the age of forty, taking the full title Phra Bat Somdet Phra Si Sanphet Borom Racha Maha Kasat Bowon Sucharit Thosaphit Thammarat Chetthalok Nayok Udom Bromnathbophit. He became the last monarch of Ayutthaya. Among the general populace, he was commonly referred to as Khun Luang Kheeruean, due to suffering from leprosy or a chronic skin disease. His conduct was often considered improper, which diminished public reverence and faith in his rule.

Shortly thereafter, Krom Muen Thepphiphit, who had entered the monkhood, conspired with Phra Ya Aphai Racha and Phra Ya Ratchaburi (Phra Ya Phetchaburi) to invite King Uthumphon to reclaim the throne. They reported their plan to the monk-king Uthumphon, who pleaded that no harm be done to the conspirators. King Ekathat, upon learning of the plot, ordered Krom Muen Thepphiphit to be exiled to Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka), while the other officials involved were imprisoned. (S. Plai Noi, 2003: 150–153, Encyclopedia of Thai History)

Since King Ekathat ascended the throne, government officials became disorderly, and some resigned from service. A French missionary recorded at the time: “…the country was in turmoil, for the inner court (royal consorts) held power equal to the king. Those guilty of treason, murder, or arson were supposed to face the death penalty, but the greed of the inner court changed the punishment to confiscation of property, all of which fell into the hands of the inner court. (According to Burmese chronicles, King Ekathat had four queens, 869 concubines, and over 30 royal relatives; Khajorn Sukphanich, 2002: 269). Seeing the greed of the inner court, officials sought to exploit accused persons for their own gain, worsening the suffering of the populace…” Seeing their superiors act this way, subordinates imitated them, resulting in widespread oppression and injustice. Those with wealth could use it to evade punishment, leaving ordinary people with no protection. Public morale and unity declined, and civil officials lost motivation. When the Burmese attacked Ayutthaya in 1767 (B.E. 2310), King Ekathat attempted to flee the city by boat with a courtier, but the Burmese found him at Ban Chik, near Wat Sangkhawat, after he had fasted for more than ten days. Upon reaching the camp at Pho Sam Ton, he died. (Knowledge about Thonburi, 2000: 162) However, the Royal Chronicles in the king’s letter state that “after soldiers found the royal body in the bushes near Ban Chik, he had died from starvation; it was later intended to bring the body back to the capital for cremation after the war.” (Pramin Khruathong, 2002: 36) Chusiri Chamraman (1984: 64) and Khajorn Sukphanich (2002: 269) wrote: “…Burmese records indicate that the Thai king, his queens, and royal children tried to disguise themselves and escape through the western city gate (some accounts say from the royal palace’s west gate), but the king was struck by a stray bullet and died…”

According to Burmese chronicles, the Burmese army entered the capital at around 4 a.m. on Thursday, the 11th day of the waxing moon, April 1767 (B.E. 2310), corresponding to the year 1129 of the Burmese era. Upon entering the city, the Burmese set fire to houses and temples, and confiscated countless valuables while taking men and women as captives.

When King Ekathat saw the capital fall, he disguised himself along with the entire royal family and fled through the western gate, coinciding with the Burmese troops entering the city, causing confusion and chaos. King Ekathat was struck by gunfire and died there, though no one knew of his death at the time. The next day, Burmese soldiers captured one of his younger brothers, who during the war had been imprisoned in chains, to lead them to the person who could recognize the king’s face. Ultimately, they discovered the royal body at the western gate and brought it back for cremation. (Sunet Chutintharanon, 1998: 68)

M. Turpin (translated by S. Siwarak, 1967: 57) stated, “The king attempted to flee, but someone recognized him, and he was killed at the palace gate itself.”

The Burmese Hmannan Yazawin chronicle aligns with Thai sources, as the Khamluang Khao (Chronicles of the Ayutthaya Court) states that King Ekathat hid for about eleven to twelve days before dying. (Rong Sayamarn, 1984: 43, from Historical Report, Vol. 18, No. 1, January–December 1984) Somporn Thepsittha (1997: 31) wrote that King Ekathat fled the Burmese and hid in the forest outside the city, where he died in seclusion. The Burmese later discovered his royal attire and regalia, and Nemyo Sithu ordered the body to be buried. Sukee Phra Nayokong transported the royal body to be interred at Khok Phra Meru in front of the Vihara Si Sanphet (but Ruam Sak Chai Komin, 1994: 18–20, notes that it was buried in front of the Vihara Phra Mongkhon Bophit). Later, King Taksin the Great ordered the exhumation of the royal body for cremation. (Foundation for the Preservation of the Former Royal Palace, 2000: 162)

Note:

Phra Thinang Suriya Marinthra (also called Suriya Samrinthra) was mentioned by King Chulalongkorn in his commentary on the royal palaces of the old capital, stating, “The name Phra Thinang Suriya Marinthra first appeared during the reign of King Phetracha, when the royal remains of King Narai were brought from Lopburi and enshrined at Phra Thinang Suriya Marinthra. At that time, there were three palaces: Vihara Si Sanphet Prasat and Bencharat Mahaprasat. The first two names remain, and it should be understood that Phra Thinang Bencharat was renamed Phra Thinang Suriya Marinthra because it was by the river, and the royal remains were brought by boat and placed there… The term Phra Thinang Suriya Samrinthra appeared later, after King Borommakot. It seems that he changed Suriya Marinthra to Suriya Samrinthra to harmonize the names of the three palaces.” Later, when King Ekathat resided in this throne hall after ascending the throne, it was referred to in the Royal Chronicles as Phra Thinang Suriya Samrinthra. (S. Plai Noi, 2003: 406–407)

2.6 What was the condition of Ayutthaya before it fell to the Burmese?

First, it is necessary to identify the causes of Ayutthaya’s decline. The weakening of the kingdom occurred due to several factors, which are as follows:

Weakness in Ayutthaya’s defense system arose from divisions within the royal family, which competed for the throne and split into factions. This began when King Songtham (B.E. 2171–2173) seized the throne from Prince Si Sava Pak (B.E. 2163), during which many officials were killed.

Later, during the reign of King Prasat Thong (B.E. 2172–2231), officials who had supported King Chetthathirat (B.E. 2171–2173) were killed, though not in large numbers. During the reign of King Narai the Great (B.E. 2199–2231), officials allied with Prince Chai and Prince Si Suthammaracha were almost entirely eliminated, requiring the king to employ foreign and non-Thai officials, including Indian, Lao, and European officers such as Phraya Ramdecho, Phraya Ratchawangsan, Phraya Siharatchadecho, and Chao Phraya Wichayen, among others (from the Ayutthaya Chronicles, pp. 67–68). While King Narai was ill at the Lopburi palace, Phetracha and Khun Luang Sorasak began eliminating royal relatives, Thai officials, and foreign officials who were rivals or favored the French. During King Phetracha’s reign (B.E. 2231–2246), he appointed Prince Si Suwan as royal consort, and elevated his daughters, daughters of King Narai, to queens on the right and left sides, respectively, after previously honoring his former consort as the central queen. When the two new queens each gave birth to a son, King Phetracha favored these princes because they were grandsons of King Narai, who was highly respected by officials. Although Khun Luang Sorasak remained the uparaja, he distrusted these royal sons, one being Chao Phraya Khwan and the other Phra Trasanon. Their mother built a palace near Wat Phutthaisawan, and when they reached thirteen, they underwent the so-kan rite and were ordained as novices for five years, studying the Buddhist scriptures thoroughly. They later disrobed to study various secular subjects and, upon reaching the proper age, were ordained as monks, thereby escaping royal danger. Furthermore, during King Phetracha’s reign, military campaigns against Nakhon Si Thammarat and Nakhon Ratchasima likely resulted in the deaths of many skilled officials.

Wat Phutthaisawan

Although the reign of King Sanphet VIII (Phra Chao Suea) lasted only six years (B.E. 2246–2251) and the reign of King Phumintharacha, or King Thai Sa (B.E. 2251–2275), lasted 24 years, together spanning 30 years, there were no major wars with foreign powers. However, toward the end of King Phumintharacha’s reign, internal conflict arose again. Prince Aphai and Prince Poramet, sons of the king, fought against the uparaja, Prince Phon, their uncle. The latter triumphed and ascended the throne as King Boromkosa, also known in Thai historical accounts as King Boromkosa (Somdet Phra Chao Boromkosa), possibly because he was the last monarch of Ayutthaya whose royal remains were enshrined in a royal coffin. (Insight by Professor Mom Chao Suphatradis Diskul)

During this reign, the kingdom prospered in many ways and grew wealthy through trade, yet internal strife occurred again. Toward the end of the reign, the king’s three sons formally reported that the uparaja, Prince Thammathibet, had committed adultery with the chief consort, Princess Sangwan, a daughter of King Phumintharacha. Their claims were verified as true, and both were subsequently punished by death.

As for Somdet Phra Chao Ekathat, before ascending the throne, he was known as Krom Khun Anurak Montri. His royal father, King Boromkhos, was well aware that this son was unsuitable to be king. When the first uparaja was executed, the king bypassed him and appointed his third son, Chao Fa Uthumphon, as the uparaja. However, after King Boromkhos passed away and Chao Fa Uthumphon was crowned king, he reigned for less than three months before Chao Fa Ekathat, Krom Khun Anurak Montri, declared himself king. The king’s three sons (Krom Muen Chitsunthorn, Krom Muen Sunthorn Thep, and Krom Muen Sepphakdi) were dissatisfied and attempted rebellion, but they were discovered and executed. Somdet Phra Chao Uthumphon, his younger half-brother, decided to ordain as a monk, likely motivated by his peaceful nature. This decision contributed to neglect in governance, allowing the Burmese to recognize the opportunity and invade Siam. During the first Burmese invasion in 1759, he still acknowledged his duties and temporarily left the monkhood at the request of senior officials to lead the defense. Yet, after five years without Burmese attacks, when Somdet Phra Chao Ekathat again presented himself as king, Uthumphon returned to monkhood and never resumed active leadership, culminating in the fall of Ayutthaya to the Burmese in 1767. Chao Fa Uthumphon’s behavior, which earned him the title “Khun Luang Ha Wat,” also affected the kingdom’s fate; if he had exercised greater involvement in state affairs and acknowledged that his elder brother was unfit to rule during a critical wartime period, there would have been a five-year window (1759–1764) to address the kingdom’s deficiencies. Instead, the lapse in leadership and Ekathat’s preoccupation with personal comfort contributed directly to Ayutthaya’s ultimate downfall.

Khun Luang Ha Wat (Chao Fa Uthumphon) withdrew from state affairs entirely, dedicating himself solely to religious practice. In summary, those in the position of national leadership failed to fulfill their duties: one ruler lacked all capability and could not govern effectively, while the other, though devoted to his elder brother in a misguided way, pursued religious practice to the exclusion of concern for the state, leaving the kingdom vulnerable during a critical period of crisis.

It can be said that during the Phlu Luang dynasty, even though the kingdom experienced more than 60 years without major wars with foreign powers, the first cause of Ayutthaya’s decline was the internal strife and distrust among the royal family and officials, stemming from factionalism and disunity within the ruling elite.

In summary, during the reign of the Phlu Luang dynasty, Ayutthaya’s political stability was undermined by power struggles between nobles and the king. The power base of provincial governors grew rapidly, prompting Ayutthaya to weaken the provinces through suppression and strict regulations, including forbidding communication among governors to prevent any from amassing enough strength to rebel against the capital. This deliberate weakening of the provinces effectively destroyed Ayutthaya’s self-defense system. The kingdom could not recruit sufficient troops from the weakened provinces to defend the capital. When the Burmese army approached, Thai forces were unable to stop them, and the majority of people lacked the morale to resist seriously, resulting in widespread panic, desertion, and chaos.

2. Complacency and Negligence: From the monarch down to officials in the capital and provincial centers, as well as the general populace (except for some minority groups), everyone exhibited complacency. Most commoners sought only personal comfort and convenience, while the ministers and officials neglected to maintain and defend the kingdom.

King Alaungpaya of Burma waged war to subjugate the Mon towns and, in March 1759 (B.E. 2302), led his army across into Thai territory from the southwest, following the Mon. He began by capturing Mergui, a port city of the Ayutthaya Kingdom, as well as Tavoy and Tenasserim, without facing resistance from the Thai side. He then advanced over the mountains and along the coast, seizing Kui, Pran, Phetchaburi, and Ratchaburi, before moving north toward Suphanburi, ultimately besieging Ayutthaya for 2–3 months. The response from Ayutthaya was minimal because the kingdom had fallen into complacency; after decades of peace with no external wars, the military had been neglected, troops were untrained, and the male population had lost enthusiasm for soldiering.

Before King Alaungpaya could fully cross into Thai territory, he passed away. His eldest son, known in Thai sources as Manglauk (called Naungdawgyi in Burmese), ascended the throne but reigned only three years before passing away. During his brief reign, he had to suppress rebellions by relatives and contend with local governors vying for territory, and these matters remained unresolved when he died in November 1753 (B.E. 2306). His younger brother, referred to in Thai sources as Mangra and in Burmese as Ma Yadau Meng (better known as Hsinbyushin), then became king and continued administering the country. Consequently, Burma did not invade Thailand for five years, yet the Thai side remained complacent. King Ekathat did not strengthen the army, there is no record of appointing competent generals, and soldier training was neglected. Weapons were not stockpiled, even though Western foreigners—Portuguese, who had taught and sold cannons to Siam for centuries, and later the English, Dutch, and French—continued to trade, provide military knowledge, and propagate religion. According to correspondence and chronicles from French missionaries and Dutch merchants, summarized in the Fine Arts Department’s compilation in Volume 39 of the Thai Chronicles, it is noted that “King Ekathat, unable to find capable Thai officers, relied on foreigners who were not professional soldiers and could only help to a limited extent. Armaments were insufficient, and recurring rebellions in the provinces were dealt with by executions, further weakening the military.” Instead of reforming the kingdom’s defenses or addressing the underlying causes of rebellion, he resorted to ad hoc, short-term measures, displaying negligence and lacking long-term planning in both governance and national defense.

When the officials realized that the king was lacking in capability, they ought to have assisted in some way, such as promoting military training or petitioning the king to prepare the kingdom’s defenses. It was evident that when Mangra (or King Shinbawshin) ascended the throne in Burma, he had consolidated his forces just as King Alaungpaya had done. It was also well known that he had previously laid siege to Ayutthaya alongside his father (King Alaungpaya), so he would have been familiar with escape routes within the Thai territory as well as the weaknesses in Thai military skills. Thailand should have taken this opportunity to improve training, battle tactics, and the effective use of weaponry, but instead, we were heedless and left without any corrective measures.

Even though the Burmese king (King Mangra) did not personally lead the campaign as King Alaungpaya once did, he was familiar with the shortcut routes into western Thailand and sent his army along the same route as in 2306 BE. Thailand, however, had made no preparations to resist the Burmese, openly displaying negligence. The Burmese forces thus advanced comfortably across the Thai border, capturing various towns and reaching Ratchaburi, where they rested for four days. When Thai troops went out to patrol, they encountered the Burmese army, whose commander was recorded in Burmese sources as Okya Yawunthan. Later, when Thailand sent forces to oppose the Burmese, the weapons were inadequate, and neither officers nor soldiers were properly trained, resulting in defeat. Even though the local Thai villagers, who were less well-armed—such as those from Wiset Chai Chan and Bang Rachan—resisted fiercely, the Burmese had to employ various strategies. Despite their courage, these defenders ultimately all perished.

Note: The heroism of the villagers of Bang Rachan

In 1764 CE (B.E. 2307), the Burmese army advanced into Thai territory to conduct reconnaissance because Thailand was undergoing internal transitions of power. The Burmese forces reached Suphanburi and Singburi, but the Thai army under King Ekkathat had not yet mobilized to resist the invaders. Consequently, the Burmese army advanced as far as Bang Rachan village in Singburi Province.

The Monument of the Ban Bang Rachan Villagers

Ban Bang Rachan Camp

(Image from Rattanakosin Sculpture Album and Encyclopedia of Central Thai Culture, Vol. 3)

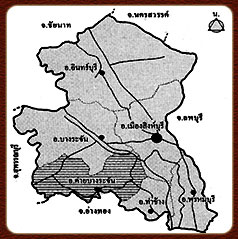

A schematic map showing the location of Ban Bang Rachan Camp, Singburi Province

(Image from Encyclopedia of Central Thai Culture, Central Region, Vol. 3: Kang Khao Kin Kluay, Phleng–Chittrakam Krabuan Chin)

The villagers of Bang Rachan and the people of Mueang Saen united under the leadership of Phra Kru Thammachoti and 11 village chiefs, namely:

1. Mr. Thaen, a villager from Si Bua Thong, Mueang Sing Buri District

2. Mr. In, a villager from Si Bua Thong, Mueang Sing Buri District

3. Mr. Mueang, a villager from Si Bua Thong, Mueang Sing Buri District

4. Mr. Chot, a villager from Si Bua Thong, Mueang Sing Buri District

5. Mr. Dok, a villager from Krab, Wiset Chai Chan District

6. Mr. Thongkaew, a villager from Pho Thale, Wiset Chai Chan District

7. Khun San Sapkij (Thanong), official of Sankhaburi

8. Mr. Phan Rueang, headman of Bang Rachan Subdistrict

9. Mr. Thong Saeng Yai, assistant headman of Bang Rachan Subdistrict

10. Mr. Chan Khiao or Chan Nuad Khiao, headman of Pho Thale

11. Mr. Thong Men, village chief

The villagers of Bang Rachan fought the Burmese invaders with courage and determination in seven battles. In the final encounter, the Burmese sent a Mon commander, Suki Nayakong, who had grown up in Thailand and knew the escape routes, to attack Bang Rachan Camp. He used artillery to bombard the camp, causing daily casualties among the villagers. Khun San then led part of the villagers to Ayutthaya to request cannons from the king to fight the Burmese, but the Ministry of War advised against granting the request, fearing the artillery might be captured by the Burmese and used to bombard Ayutthaya. Phra Ajahn Thammachoti (of Wat Khao Bang Bo) took the lead in casting cannons three times: the first two cannons broke and were unusable, and the third fired only one shot before exploding. Ultimately, the villagers had no choice but to evacuate the women and children by carts, sneaking them out from the rear to escape the siege.

At dawn, after taking their final meal, the villagers of Bang Rachan bravely charged out of the camp to fight the enemy, showing no fear of death. Suki Nayakong ordered the cannons to fire upon them, tearing the villagers apart. Those who survived the bombardment pressed forward to fight the vastly superior Burmese forces, only to be killed, their blood soaking the land of Thailand. Bang Rachan Camp fell on Monday, the 2nd waning day of the 8th lunar month, Year of the Dog, after five months of fierce resistance. Eventually, the Burmese succeeded in surrounding Ayutthaya (Somporn Thepsittha, 1997: 19-20).

Later, the patriots of Sing Buri Province, together with the Thai people, united to build a monument in honor of the courage, patriotism, and sacrifice of their ancestors. His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej graciously presided over the opening ceremony on Thursday, 29 July 1976. Every year on 4 February, the government designates a commemorative day to honor the heroic deeds of these brave ancestors (http://kanchanapisek.or.th/kp8/sbr/sbr203.html, 15/7/2004).

Another cause of negligence was that the Thais were unprepared to defend the country. They failed to learn from the previous siege of Ayutthaya by King Alaungpaya of Burma, who had employed decisive strategies such as using cannons at close range and cultivating rice fields to stockpile provisions. The Thais carelessly allowed the Burmese to farm and did not prepare sufficient supplies in advance, relying on the old assumption that the Burmese would retreat when the flood season arrived. When the Burmese stayed for over a year without retreating, building boats and farming themselves, the Thais focused solely on defending Ayutthaya, leaving the outlying cities to fend for themselves. They even summoned capable provincial commanders, such as Phraya Taksin and others, to assist in defending the capital, but placed them under the strict control of the king, who lacked military command skills. Thus, even skilled officers could not resist the Burmese effectively. Severe punishments discouraged provincial nobles from mobilizing forces to assist, and no one dared act without direct orders. Nevertheless, after Ayutthaya fell in early 1767, capable individuals from the north, south, and northeast gathered to form various factions, demonstrating ambition and rivalry rather than a unified effort to restore independence (Chusiri Jamman, 1984: 58–60).

3. The Inefficient Administrative System of Ayutthaya

At least two issues can be identified: the disorder in the corvee (labor) system and deficiencies in intelligence gathering (Foundation for the Conservation of the Ancient Palace, 2000: 33–34).

3.1 Disorder in the corvee system caused the central authority to lose a large number of manpower to nobles and provincial governors. Many avoided registering with the central administration, making troop organization difficult and leaving fewer soldiers than necessary. This resulted in an inability to dispatch large armies to intercept Burmese forces along their advance routes.

3.2 Deficiencies in intelligence gathering led to confusion about Burmese troop movements and strength. The Thai forces had to spread out over various locations, leaving their forces scattered, weak, and disorganized, and the Thai army was repeatedly defeated and forced to retreat to Ayutthaya whenever confronted by the Burmese.

The chaos, confusion, and weakness that arose during the collapse of Ayutthaya may have been partly due to leadership failures. It can even be said that the Ayutthaya kingdom never had a real opportunity to confront its enemies in the manner that a kingdom should.

4. The Cunning Strategy of Burma to Conquer Ayutthaya

Burma devised a shrewd plan to conquer Ayutthaya by sending two armies to flank the capital from both the north and the south. Employing guerrilla warfare over the course of three years, they captured surrounding towns until the northern and southern forces converged at the end of 1765. The Burmese then laid siege to Ayutthaya until 1767. On April 8, 1767, the walls of Ayutthaya were breached, and the Burmese army stormed the city, seizing people and valuables, and setting fire to the city and its temples. Ayutthaya’s downfall was not merely a material destruction but also a spiritual devastation, as the sacred objects that embodied the Thai people’s faith and morale—the very “spirit of the city”—were annihilated to prevent the restoration of the kingdom. The fall of Ayutthaya, therefore, was not simply the loss of independence to another state, but the complete disintegration of a once-prosperous kingdom, leaving behind only its name for future generations to remember. (The Foundation for the Conservation of Ancient Monuments in the Old Palace, 2000: 35–36)

Pharadee Mahakhan (1983: 11–12) summarized the causes of Ayutthaya’s decline as follows:

1. The instability of the monarchy. Although, in theory, the kings of Ayutthaya were both the sovereign rulers and the ultimate authority of the land—absolute monarchs—in practice, very few were able to maintain their royal power securely. Historical records of the Ayutthaya period show frequent struggles for power and usurpations of the throne. During the 417 years of the kingdom’s existence, only 20 monarchs successfully retained the throne without being overthrown or deposed. Under an absolute monarchy, the instability of the royal institution inevitably signified internal political instability as well.

2. Internal conflicts among the ruling class of the Ayutthaya Kingdom. These conflicts took various forms, including disputes between the king and members of the royal family, conflicts within the royal family itself, struggles between nobles and the king, between nobles and the royal family, and even among the nobles. Such internal discord directly affected the efficiency of governance, the stability of the economy, and the kingdom’s capability to defend and preserve its realm.

3. The administrative system lacked efficiency. Specifically, the control over manpower and the governance of territories were not effectively managed. Frequent riots and rebellions occurred, undermining the authority and stability of the kingdom.

4. The enemies were stronger and had already prepared countermeasures against the strategic tactics that the Ayutthaya Kingdom had previously employed successfully.

Due to these various causes, Ayutthaya was unable to maintain its stability and ultimately fell to the Burmese on April 8, 1767.

Major General Janya Prachitromrun (1993: 193–194) summarized the causes of Ayutthaya’s fall to Burma as follows:

1. King Ekkathat was a weak monarch lacking capability and wisdom. His nine-year reign was a complete failure in the governance of the kingdom.

2. The condition of the nation deteriorated due to struggles for the throne—what would today be termed a coup d’état rather than a revolution—since the government remained under the absolute monarchy system.

3. The members of the royal family were disunited, each seeking personal power and influence. They played little role in the administration of state affairs except during times of war when Ayutthaya faced invasion. During King Ekkathat’s reign, government officials also frequently fell into discord.

4. The kings of the Ban Phlu Luang Dynasty scarcely developed the country. Agriculture, the principal occupation of the people, received little improvement or support, and trade continued in the same traditional manner as before.

5. Had the Alaungpaya Dynasty—particularly King Hsinbyushin—not ruled Burma, Ayutthaya might have escaped invasion and destruction. Hsinbyushin was firmly determined to conquer Ayutthaya. Although the Ayutthaya court was aware of this and attempted to strengthen its defenses and accumulate weapons, the efforts were insufficient, likely due to a lack of financial resources for such expenditures.

Note

Prophecy Verse Predicting the Fate of Ayutthaya

จะกล่าวถึงกรุงศรีอยุธยา

เป็นกรุงรัตนะราชพระศาสนา … มหาดิเรกอันเลิศล้น

เป็นที่ปรากฏรจนา … สรรเสริญอยุธยาทุกแห่งหน

ทุกบุรีสีมามณฑล … จบสกลลูกค้าวาณิช

ทุกประเทศสิบสองภาษา … ย่อมมาพึ่งกรุงศรีอยุธยาเป็นอกนิษฐ์

ประชาราษฎร์ปราศจากภัยพิษ … ทั้งความวิกลจริตและความทุกข์

ฝ่ายองค์พระบรมราชา … ครองขัณฑสีมาเป็นสุข

ด้วยพระกฤษฏีกาทำนุก … จึงอยู่เป็นสุขสวัสดี

เป็นที่อาศัยมนุษย์ในใต้หล้า … เป็นที่อาศัยแก่เทวาทุกราศี

ทุกนิกรนรชนมนตรี … คฤหบดีพราหมณ์พฤฒา

ประดุจดังศาลาอาศัย … เหมือนหนึ่งร่มพระไทรสาขา

ประดุจหนึ่งแม่น้ำคงคา … เป็นที่สิเนหาเมื่อกันดาร

ด้วยพระเดชเดชาอานุภาพ … อาจปราบไพรีทุกทิศาน

ทุกประเทศเขตขัณฑ์บันดาล … แต่งเครื่องบรรณาการมานอบนบ

กรุงศรีอยุธยานั้นสมบูรณ์ … เพิ่มพูนด้วยพระเกียรติขจรจบ

อุดมบรมสุขทุกแผ่นภพ … จนคำรบศักราชได้สองพัน

คราทีนั้นฝูงสัตว์ทั้งหลาย … จะเกิดความอันตรายเป็นแม่นมั่น

ด้วยพระมหากษัตริย์มิได้ทรงทศพิธราชธรรม์ … จนเกิดเข็ญเป็นมหัศจรรย์ 16 ประการ

คือดาวเดือนดินฟ้าจะอาเพศ … อุบัติเหตุเกิดทั่วทุกทิศาน

มหาเมฆจะลุกเป็นเพลิงกาฬ … เกิดนิมิตพิศดารทั้งบ้านเมือง

พระคงคาจะแดงเดือดเป็นเลือดนก … อกแผ่นดินจะบ้าฟ้าจะเหลือง

ผีป่าก็จะวิ่งเข้าสิงเมือง … ผีเมืองนั้นจะออกไปอยู่ไพร

พระเสื้อเมืองก็จะเอาตัวหนี … พระกาฬกุลีจะเข้ามาเป็นไส้

พระธรณีจะตีอกไห้ … อกพระกาฬจะไหม้อยู่เกรียมกรม

ในลักษณะทำนายไว้บ่อห่อนผิด … เมื่อพินิจพิศดูก็เห็นสม

มิใช่เทศกาลร้อนก็ร้อนระงม … มิใช่เทศกาลลมลมก็พัด

มิใช่เทศกาลหนาวก็หนาวพ้น … เกิดวิบัตินานาทั่วสากล

เทวดาผู้รักษาพระศาสนา … จะรักษาแต่คนฝ่ายอกุศล

สับปุรุษจะแพ้แก่ทุรชน … มิตรตนจะฆ่าซึ่งความรัก

ภรรยาจะฆ่าซึ่งคุณผัว … คนชั่วจะล้างผู้มีศักดิ์

ลูกศิษย์จะสู้ครูพัก … จะหาญหักผู้ใหญ่ให้เป็นน้อย

ผู้มีศีลจะเสียซึ่งอำนาจ … นักปราชญ์จะตกต่ำต้อย

กระเบื้องจะเฟื่องฟูลอย … น้ำเต้าอันลอยจะถอยจม

ผู้มีตระกูลจะสูญเผ่า … เพราะจัณฑาลมันเข้ามาเสพย์สม

ผู้ทรงศีลจะเสียซึ่งอารมณ์ … เพราะสมัครสมาคมด้วยมารยา

พระมหากษัตริย์จะเสื่อมสิงหนาท ประเทศชาติจะเสื่อมซึ่งยศฐา

อาสัตย์จะเลื่องฤๅชา … พระธรรมจรรยาฤๅกลับ

ผู้กล้าจะเสื่อมใจหาญ … จะสาบสูญวิชาการทั้งปวงสรรพ

ผู้มีสินจะถอยจากทรัพย์ … สับปุรุษจักอับซึ่งน้ำใจ

ทั้งอายุขัยจะถอยเคลื่อนเดือนปี … ประเวณีจะรวนตามวิสัย

ทั้งพืชแผ่นดินจะผ่อนหย่อนไป … ผลหมากรากไม้จะถอยรส

ทั้งเภทพรรณว่านยาก็อาเพศ … เคยเป็นคุณวิเศษก็เสื่อมหมด

จวงจันทร์พรรณไม้อันหอมรส … จะถอยถดไปตามประเพณี

ทั้งข้าวก็จะยากหมากจะแพง … สารพันจะแห้งแล้งเป็นถ้วนถี่

จะบังเกิดทรพิษมิคสัญญี … ฝูงผีจะวิ่งเข้าปลอมคน

กรุงประเทศเขตราชธานี … จะบังเกิดการกุลีทุกแห่งหน

จะอ้างว้างจากใจทั้งไพร่พล … จะสาละวนทั่วโลกทั้งหญิงชาย

จะร้อนอกสมณาประชาราษฏร์ … จะเกิดเข็ญเป็นอุบาทว์นั้นมากหลาย

จะรบราฆ่าฟันกันวอดวาย … ผู้คนจะล้มตายกันเป็นเบือ

ทั้งทางน้ำก็จะแห้งเป็นทางบก … เวียงวังก็จะรกเป็นป่าเสือ

แต่สิงสาราสัตว์เนื้อเบื้อ … จะหลงหลอเหลือในแผ่นดิน

ทั้งฝูงคนสารพัดสัตว์ทั้งหลาย … จะสาบสูญล้มตายเสียหมดสิ้น

ด้วยพระกาฬจะมาผลาญซึ่งแผ่นดิน … จะสูญสิ้นด้วยการณรงค์สงคราม

กรุงศรีอยุธยาจะสูญแล้ว … จะกลับรัศมีแก้วทั้งสาม

ไปจนคำรบปี เดือน คืน ยาม … จะสิ้นนามศักราชถ้วนห้าพัน

กรุงศรีอยุธยาเกษมสุข … แสนสนุกสุขล้ำเมืองสวรรค์

จะเป็นเมืองแพศยาอาธรรม์ … นับวันจะเสื่อมสูญเอย .

(Copied from http://www.pantip.com/cafe/writer/topic/W2537795/W2537795.html, September 1, 2004)

Thai Prophecy Verse on Ayutthaya

คราทีนั้นฝูงสัตว์ทั้งหลาย

จะเกิดความอันตรายเป็นแม่นมั่น

ด้วยผู้มีอำนาจขาดทศพิธราชธรรม์

จึงเกิดเข็ญเป็นอัศจรรย์สิบหกประการ

คือดาวเดือนดินฟ้าจะอาเพศ

อุบัติเหตุเกิดทั่วทุกทิศาน

มหาเมฆจะลุกเป็นเพลิงกาฬ

เกิดนิมิตพิศดารทุกบ้านเมือง

พระคงคาจะแดงเดือดดั่งเลือดนก

อกแผ่นดินจะบ้าฟ้าจะเหลือง

ผีป่าก็จะวิ่งเข้าสิงเมือง

ผีเมืองนั้นจะออกไปอยู่ไพร

พระเสื้อเมืองจะเอาตัวหนี

พระกาฬกุลีจะเข้ามาเป็นไส้

พระธรณีจะตีอกไห้

อกพระกาฬจะไหม้อยู่เกรียมกรม

ในลักษณะทำนายไว้บ่ห่อนผิด

เมื่อวินิจพิศดูก็เห็นสม

มิใช่เทศกาลร้อนก็ร้อนระงม

…………………………….( ตก )

………………………………( ตก )

มิใช่เทศกาลฝนก็จะอุบัติ

ทุกต้นไม้หย่อมหญ้าสารพัด

เกิดวิบัตินานาทั่วสากล

เทวดาซึ่งรักษาพระศาสนา

จะรักษาแต่คนอกุศล

สัปปุรุษจะแพ้แก่ทรชน

มิตรตนจะฆ่าซึ่งความรัก

ภรรยาจะฆ่าซึ่งคุณผัว

คนชั่วจะมล้างผู้มีศักดิ์

ลูกศิษย์จะสู้ครูพัก

จะหาญหักผู้ใหญ่ให้เป็นน้อย

ผู้มีศีลจะเสียซึ่งอำนาจ

นักปราชญ์จะตกต่ำต้อย

กระเบื้องจะเฟื่องฟูลอย

น้ำเต้าอันน้อยจะถอยจม

ผู้มีตระกูลจะสูญเผ่า

เพราะจัณฑาลมันเข้ามาเสพสม

ผู้มีศีลนั้นจะเสียซึ่งอารมณ์

เพราะสมัครสมาคมด้วยมารยา

พระมหากษัตริย์จะเสื่อมซึ่งสีหนาท

ประเทศราชจะเสื่อมซึ่งยศถา

อาสัตย์จะเลื่องลือชา

พระธรรมจะตกลึกลับ

ผู้กล้าจะเสื่อมในหาญ

จะสาบสูญวิชาการทั้งปวงสรรพ

ผู้มีสินจะถอยจากทรัพย์

สัปปุรุษจะอับซึ่งน้ำใจ

ทั้งอายุจะถอยเคลื่อนจากเดือนปี

ประเวณีจะแปรปรวนตามวิสัย

ทั้งพืชแผ่นดินจะผ่อนไป

ผลหมากรากไม้จะถอยรส

ทั้งแพทย์พรรณว่านยาก็อาเพศ

เคยเป็นคุณวิเศษก็เสื่อมหมด

จวงจันทร์พรรณไม้อันหอมรส

จะถอยถดไปตามประเพณี

ทั้งข้าวจะยากหมากจะแพง

สารพัดแห้งแล้งเป็นถ้วนถี่

จะเกิดทรพิษมิคสัญญี

ฝูงผีจะวิ่งเข้าปลอมคน

กรุงประเทศราชธานี

จะเกิดการกุลีทุกแห่งหน

จะอ้างว้างอกใจทั้งไพร่พล

จะสาละวนทั่วโลกทั้งหญิงชาย

จะร้อนอกสมณะประชาราษฎร์

จะเกิดเข็ญเป็นอุบาทว์นั้นมากหลาย

จะรบราฆ่าฟันกันวุ่นวาย

ฝูงคนจะล้มตายลงเป็นเบือ …

Some literary sources attribute the Thai Prophecy Verse on Ayutthaya to King Narai the Great, while others claim it was composed by Prince Thammathibet. Some suggest it was written during the late Ayutthaya period, shortly before the fall of the kingdom. In any case, this literary work has been widely read and remembered, as the events described before Ayutthaya’s fall closely resemble those of the modern world. Another important literary work expressing similar ideas is Kap Phra Chai Suriyawong (see the era of Sunthorn Phu), which also bears resemblance to The Buddha’s Prophecy to King Pasenadi of Kosala, outlining ten predictions after the Buddha’s passing. (Komthuan Khanthanu, 1998: 105–108)